Switching Gears

A step towards sustainable credit

Hey there,

We had initially written this newsletter only for our paid readers. We are removing the paywall for a limited time for the Gearbox community.

This is the fourth article on a series of DeFi related products we have been covering. If you’d like to go down the rabbithole on a Sunday, consider exploring past pieces on dYdX, derivatives markets and interface fees.

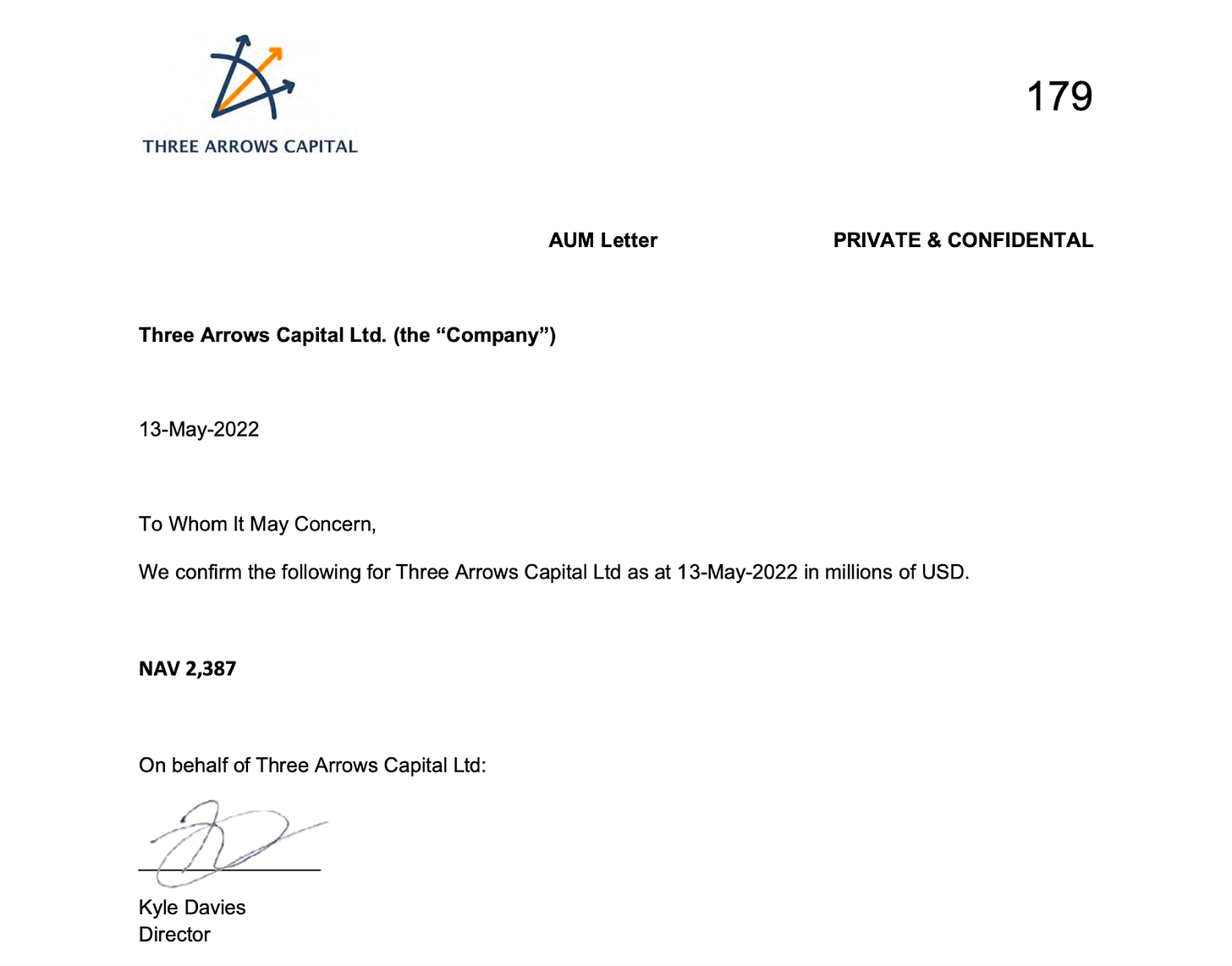

On 3rd November, Sam Bankman Fried from FTX was declared guilty of seven counts of fraud. A few weeks prior, Su Zhu from 3AC was arrested at Singapore airport for the billions of dollars worth of loans the company defaulted on last year. The year 2022 was unique for the industry. We learned a few difficult lessons. One of them was that using illiquid assets as collateral with inflated value is usually not a good idea.

Let me explain. When you stake Ethereum, the yield you get is from the protocol. There is minimal risk in that activity. But when you offer the same asset as a loan to a hedge fund (like 3AC), you don't quite know how they will use it. They could invest in a healthy mix of startups that provide outlier returns, as Alibaba did for SoftBank. They could also leverage a token backed by nothing and send signed notes to prove they still have the assets you lent them. Risk, in lending, is a spectrum.

A variation of this can be seen in the FTX fiasco, too. Had it not been for a leaked memo from CoinDesk breaking down the assets held by Alameda, the exchange may have still been around. Would it have been fraudulent because of the gaping hole in the balance sheet? Yes. But there's an argument to be made that the exchange may have continued to exist because people did not know what they were dealing with. This problem of 'not knowing what you are dealing with' is not endemic to crypto alone.

In the 1990s, Olympus Corp, a Japanese Camera manufacturer, lost billions of dollars in speculative trades. The firm's management hid the fraud until 2011 through dubious accounting practices. I won't get into the specifics of what happened, but if you consider the broad arc of finance, you will see two key factors determine its story:

The interest rate at which capital is borrowed

The risk with which it is borrowed

This video by Ray Dalio - a newsletter author from the 1980s and hedge fund mogul, is a good breakdown of the relationship between an economy and interest rates. What I want to focus on today is the second point: risk. Specifically on how risk can be contained while enabling the productive use of capital. But before we go there, let's set the stage by understanding how credit itself evolved in crypto.

(Sidenote: This book is an excellent read on the story of pricing risk and interest rates in traditional markets.)

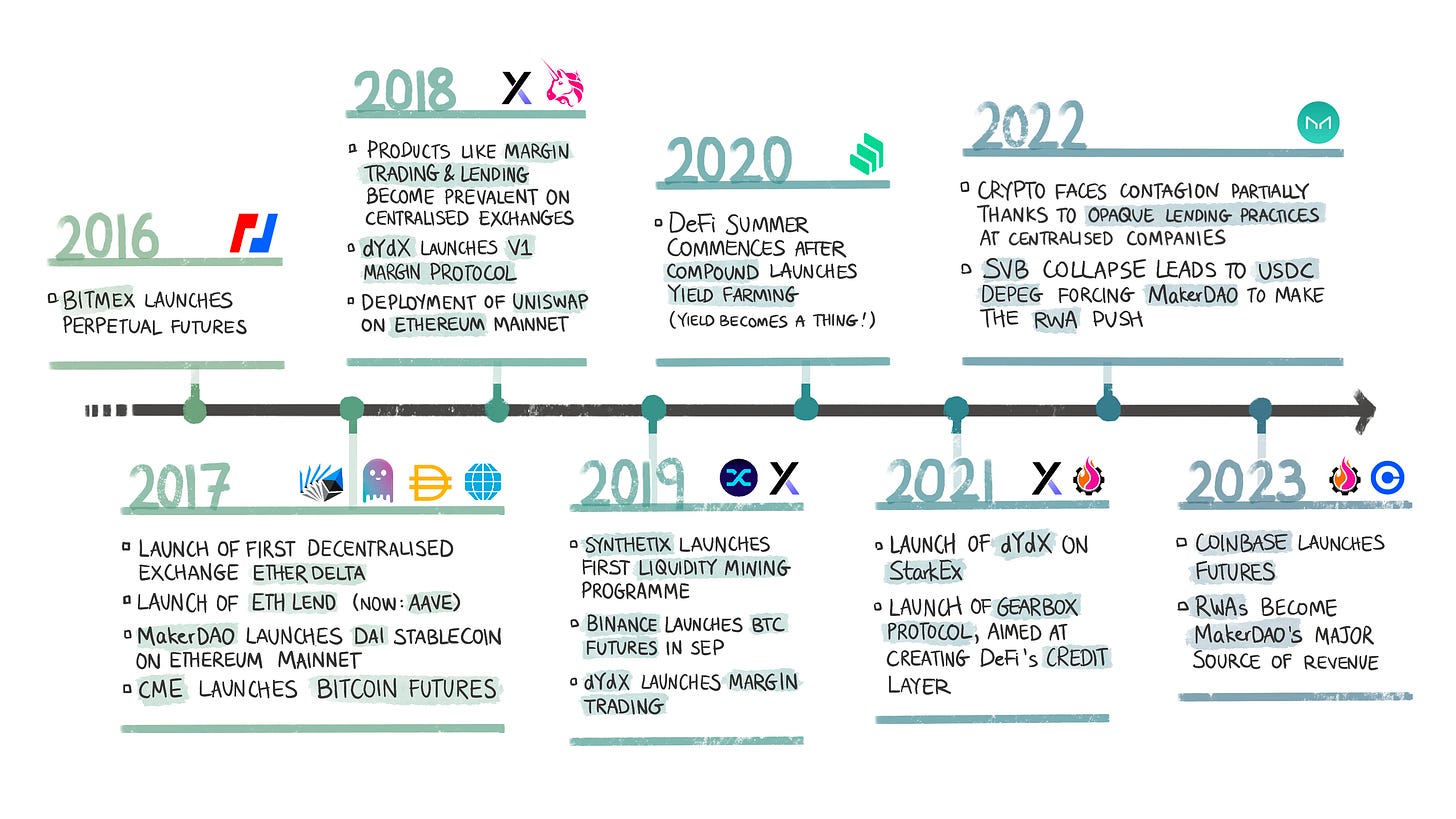

A primary source of crypto-native borrowing was perpetual futures launched on exchanges like BitMEX. The demand here was primarily from traders, and the assets could not be withdrawn from the exchange. So, all you could do was borrow assets to go long or short and pay a minor fee to the exchange. By 2017, players like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange entered the arena with their futures offering.

DeFi was still nascent, and MakerDAO was about to scale its stablecoin. To a certain degree, MakerDAO 'birthed' lending in DeFi. Users would deposit Ethereum into a smart contract and receive DAI, pegged to $1.

MakerDAO's DAI model was a godsend for many users active in the crypto ecosystem during the bear market of 2019. It allowed users to take over collateralised lines of credit to cover day-to-day expenses without selling their crypto at meager prices. Surely, many of them could have been liquidated when ETH took a journey from a high of $1,200 to a low of $110 in March 2020, but it proved that there was demand for borrowing against digital assets.

Centralised service providers like Genesis, Voyager, and Celsius saw an opportunity there, and thus, the age of centralised lending was born.

The pitch from centralised lending providers was quite straightforward: Users don't want to deal with the hindrance of bothering with on-ramps and smart contracts; perhaps we can offer yield directly to users while custodying their assets. This model would have made sense if regulations were in place that required these players to divulge their proof of reserves and sources of yield, but that was not the case.

These platforms, in turn, lent capital out to hedge funds (like 3AC and Alameda) in hopes of booking the spread. That is the difference between the interest rate passed on to users and what a hedge fund like Alameda could offer the platforms. Greed blinded the industry, risk management was considered objectionable, and anyone ringing the alarm was considered NGMI (not going to make it).

It is not that crypto stopped innovating. Right around this time, Aave and Compound launched to scale. On the derivatives side, Synthetix, dYdX and GMX came of age. But, the lack of transparency and management of risks around centralised lending protocols dragged the industry down for a while.

In 2007, Citibank's CEO famously said, 'When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance. We're still dancing.'

It is safe to say that the music stopped a year later, in 2008 when the subprime mortgage crisis happened. Crypto faced its version of the music being shut off with 3AC, FTX, and Terra last year. From these painful reminders of how contagion for credit works came a new generation of lending apps. Gearbox is one of them.

Boxing Risks

Credit or trading in DeFi consists broadly of two types – peer-to-peer (p2p) and peer-to-pool (p2pool). Order books are p2p, and AMMs are p2pool. I covered the advantages of order books over AMMs in a previous piece. But here’s a quick reminder.

AMMs allow for the aggregation of passive liquidity – that is, users come and park their capital, much like you do with your bank account.

For markets with a shortage of users and liquidity, pooling funds to facilitate activities like trading and lending/borrowing is an excellent idea. NFT lending is beginning to go from 0 to 1 with such a model.

But as this thread puts it, as the pool grows, its complexity increases. Essentially, this is what happened with the Curve exploit, which we covered here. CRV was used as collateral across lending platforms to borrow other assets without checks and balances. Following the exploit, the price of CRV dropped, putting CRV collateralised debt positions at risk.

Typically, during times like these, finding buyers gets difficult, and losses have to be socialised. A more modular approach helps contain the damage (more on this later in the article). Gearbox has been building towards that vision.

First things first. What does Gearbox do differently compared to its predecessors like Aave and Compound? It offers leverage, while lending platforms like Aave and Compound don't. This leverage is nothing but the margin from LPs. Because the LPs are owed this margin, Gearbox protocol cares about how the borrowers use these funds.

Editor’s note: An LP (liquidity provider) on Uniswap is a person depositing funds into the trading pool. On Aave, it is anybody depositing funds into the lending pool. On Gearbox, a LP provides capital into a pool assuming that other users may borrow it for leverage, much like they do on exchanges.

To 'see' how borrowers make use of the leverage obtained from Gearbox, it implements Credit Accounts (CAs). CAs turn users' wallets into smart contracts, giving the protocol a complete view of how funds are used. As a result of the insight into how borrowers are using LP funds, the protocol can limit the use of funds and create rate markets based on the risk of how funds are used. More on this later.

A feature of CAs is that when you use them, you essentially operate a piece of the Gearbox protocol. It is like renting the protocol for the time being. Think of these accounts as Ubers in a city. Once a user completes transactions through a CA, the same account can be used by another user.

Gas consumption has been a significant concern for almost all DeFi applications. Layer 2s were under construction when Gearbox was in its initial development phase. Deploying a CA takes ~$100 in a low gas fee environment. As a solution, Gearbox deployed 5,000 reusable CAs to lower the barrier for users as a part of the Credit Account Mining ceremony.

As the concurrency (the number of users who want to use the protocol through a CA simultaneously) increases, more accounts can be deployed.

The design is dictated by two major principles – modularity and composability. Although closely related, subtle differences exist between the two. Modularity is designing a system that can be divided into different parts (modules) that can be built independently and perform specific functions. Composability is when different components from multiple systems can be fused to create a new system.

Modularity allows Gearbox to create different types (governed, KYC’d, not governed at all, etc.) of pools, facilitating the creation of customised risk management (to be described later). Modular design allows for a wide credit asset base – simple tokens, LP tokens, RWAs, etc.

Getting back to the Curve example mentioned before this section, limiting how much CRV could be used as collateral would have helped contain the situation. That is, the exploit would not have turned into a contagion. This is possible with Gearbox’s modular design. There are protocol-wide limits on the exposure to collateral assets. For example, an asset’s use as collateral can be limited to $10 million. Beyond this, the asset will not be counted as collateral.

Alongside protocol-wide limits, Gearbox implements account-based limits because individual users should not be able to exhaust the entire protocol-wide limit for an asset. So, one account or a handful of accounts will not be able to use all the $10 million limit for the asset.

Composability in the above context would mean a user can use margin from Gearbox on third-party apps like Yearn or Uniswap. Until now, DeFi had little risk segregation: What I mean by that is if you have USDC and want to earn interest on it while staying on battle-tested bluechip markets, your options are limited to choosing between products like Aave, Compound, and Yearn. When you pick any option among them, you take the APY offered to you.

You don’t get to choose how your USDC gets used. And this is important because if you get to choose how it gets used (or who uses it), you can also lend it across different risk segments at different rates.

For example, a bank exposes itself to a higher risk when it lends to a micro-enterprise versus a large corporate company. But as a result, it also gets to charge a higher interest rate. As long as there is no default, banks earn more from lending to smaller companies. In the case of Gearbox, the credit account is aware of how the user is deploying borrowed funds.

If the usage of borrowed funds is deemed riskier, the user should pay a higher interest rate. As a result, lenders should also get to choose to lend to borrowers of different risk profiles. Naturally, the higher the risk, the higher the demanded interest rate.

Redesigning Lending

In our minds, Gearbox is unique because it differs from alternatives like Aave and Compound or Synthetix and GMX in a few ways.

Gearbox has better incentive alignment (no zero-sum games like GMX). It does not require its users to lose money for its LPs to make money.

With more modularity, lenders and borrowers have more flexibility in the terms on which they want to lend and borrow funds. And since Gearbox is composable with other protocols, the overall asset utilisation is likely to increase.

It has clear visibility of what the assets are used for and allows variable interest rates depending on this use.

What do I mean by that? Gearbox's design is based on margin trading, whereas Synthetix and GMX are futures trading venues. When margin trading, the counterparty is other users or market makers (or brokers in the case of traditional finance). While trading futures, the exchange is typically the counterparty.

On venues based on debt pools (like Synthetix or GMX), users trade against the pool; whenever you long or short an asset, you are trading against the house (i.e. the pooled capital). When you trade against the pool, your profit is the pool's loss, and vice versa. Either the pool wins, or you do. Both cannot win at the same time.

On Gearbox, when you borrow and open new positions, these positions are not against the house. So, the incentives of lenders and borrowers are more aligned. The assumption is that if the capital borrowed generates returns, you'd borrow more and pay more interest to lenders.

Another factor that stands out is that the protocol allows tranched risk fragmentation. What this means is when you borrow on Aave or Compound, the protocol does not have a variable interest rate depending on what the tokens are used for. The interest rate fluctuates in proportion to how much of the asset remains in the pool. Since Gearbox has a variable rate, depending on what the assets are used for, it could charge higher interest for parts of the loans offered.

Like tradfi, the interest rate charged to the borrower should be based on how the funds are used (i.e. riskier use attracts a higher interest rate). Consider the following example. Two protocols have the same utilisation rates. Protocol B implements risk fragmentation, while A doesn't. Both have $1 billion worth of lending pools. With 80% asset utilisation, protocol B earns $40 million annually while A makes $32 million.

The success of Gearbox is predicated on high demand for credit. Right now, users need to have a mandatory minimum (that precludes a lot of users) to get access to the protocol. This minimum greatly limits how much of the pool's assets are borrowed. That is set to change in the coming weeks or months.

Secondly, Gearbox wins only when the protocol’s use cases scale. That is, a user should be able to trade NFTs or invest in RWAs and possibly even bridge to another network (something like Radiant Capital, which bundles borrow and bridge). The nature of what can be used as collateral needs to be expanded, and Gearbox plans to broaden its collateral base in the coming months.

Those kinds of use cases are bottlenecked by the DAO's ability to roll out updates and vet new protocols and assets. Given the number of moving parts in an open-credit protocol like Gearbox, it may not happen fast enough to attract and retain users. Aave and Compound don't care where the assets go as of today. With Gearbox, how the assets are used is restricted. It is simultaneously a bug and a feature.

For all my critique of the protocol, the fact remains that for select use cases, it is a significantly better approach to margin/lending than what we had with Voyager, Alameda or 3AC last year. The transparency and restrictions on what the assets are used for are no longer just a feature. They are a necessity as the industry recovers from the excesses of 2021.

Hoping to see India remain unbeaten in this World Cup on Sunday night against South Africa,

Saurabh

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Ivangbi and Mugglesect for sharing their thoughts and reviewing early drafts of this article.

Disclosures

None of this is investment advice.

Members of Decentralised.co may have exposure to the assets mentioned.

Joel John, was a contributor to Gearbox during its initial months.

If you liked reading this, check these out next: