On dYdX

When apps become chains.

Hello!

A small note before we begin. Nothing written in this piece is financial advice. I am just nerding out some elementary napkin calculations and commenting on what I think. I would appreciate inputs on the model used if you are a fellow finance enthusiast.

My interest in finance keeps me looking for news from DeFi projects. On October 24, dYdX announced that their appchain was live. In the following days, dYdX proposed enhanced utility of the DYDX token.

What changes with the launch of the chain? The token (DYDX) gets three utilities instead of one:

Governance – DYDX is already the dYdX application's governance token. It now expands to be the governance token for the chain too.

Gas token – All the gas fees paid on the new chain will be in the DYDX token.

Security – As a POS-based chain, DYDX will be staked to secure the chain. As a result, stakers will get staking yield. The upside here compared to other staking is that even the fees accrued by the dYdX application (in USDC) will be distributed to stakers (and validators).

It is meaningful because, in the last 30 days, the dYdX exchange has generated over $6 million in fees. The figure is at $65 million YTD. The fees will be distributed to token holders. But how does this differ from an exchange like Uniswap?

Unlike most DEXs, dYdX is an order-book-based exchange. It matches order books off-chain, whereas most DEXs are automated-market-maker-based (AMM-based). A critical feature of providing liquidity to AMM pools is that the liquidity provider (LP) invariably ends up holding more inventory of the token that devalues compared to the other token in the pool.

Let me explain.

AMMs are typically based on the A*B = constant model, meaning the product of values (price times quantity) of the two tokens in a pool remains constant.

Say an LP adds $100 worth of tokens X and Y in a pool with a total liquidity of $1000 (after the LP adds), a 10% share of the pool. Assume the price of X is $1, and Y is $5, and the LP added 50 X and 10 Y. The pool has 500 X and 100 Y.

Product of values of X and Y = ($1 * 500) * ($5 * 100) = 250000.

Each Y is worth 5 Xs.After a few trades, assume the pool now has 1000 X and 50Y tokens. The prices are now $0.5 and $10, respectively, i.e., each Y is now worth 10 Xs. Notice the product is still ($0.5 * 1000) * ($10*50) = 250000. But the LP now has 100 X tokens (10% of 1000) and 5 Y tokens (10% of 50) with a total value of $100 instead of 50 X and 10 Y tokens (value = $125). So, the LP has lost $25 by adding liquidity to the pool.

In traditional markets, where exchanges are based on order books and derivatives markets are mature, market makers have much more flexibility around hedging. In the AMM design, hedging is constrained. As a result, providing liquidity on AMM-based exchanges is more difficult (and, thus, risky) compared to orderbook-based exchanges.

Naturally, AMM-based projects must offer more incentives to LPs. Without liquidity, there are no traders. And there are no fees or revenue without traders. So, exchanges end up sharing a significant chunk of fees with LPs.

On the other hand, since MMs on order books have more freedom to hedge their inventory, they don’t need as many incentives from the exchange. Their incentive lies in earning the spread between the bid and ask prices. For similar reasons, we saw Hubble Exchange move from AMM-based to orderbook-based designs. Often, exchanges compensate market makers via rebates to incentivise deeper liquidity.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying that the order books are better than AMMs in an absolute sense. Orderbooks require active participation and an off-chain component. AMMs are fully on-chain (so they are more transparent) and are perhaps a better choice for LPs who aren’t as active as traditional market makers.

Benchmarking Peers

The easiest way to see how DEX peers have evolved over the years is to see how much trading volume they supported and the fees they earned. Notice how spot exchanges (like Uniswap and Pancakeswap) dominated. Read this piece if you want to read more about DeFi derivatives.

The order book design allows dYdX to share all the fees with token holders and validators. This is why $75 million annual fees earned by dYdX differ from those earned by an AMM exchange. While dYdX earns fee revenue, it also spends DYDX tokens as incentives, as almost all applications do. And how does that impact applications?

The chart below compares how much token incentives exchanges have given out compared to the revenue they earned: that is, revenue generated for every $1 spent on incentives.

Every exchange needs to incentivise liquidity in some manner. Some do it with token incentives, and others do it via sharing fees with LPs.

In the chart above, ~180% for Perpetual Protocol in 2022 suggests that for every $1 they spent on incentives, token holders received $1.8 in revenues. After the recent overhaul of Synthetix, more volume started flowing through it, and it started earning more fees. As a result, for every $1 on incentives, revenue increased from ~$0.2 in 2022 to $0.8 in 2023.

GMX has a low ratio because most of its fees are shared with LPs instead of token holders. So, for GMX to give value to its token holders, either the fees need to increase a lot, or the proportion of fees shared with token holders needs to grow.

Valuing dYdX

Before delving into the valuation details, I must emphasise that all valuation models are inherently flawed. Some are more flawed than others, and this one is probably more flawed. However, I resort to this exercise because it helps me think through different projects and compare the ones belonging to the same sector using the same metrics.

The first step was to choose which models apply to a DEX like dYdX. Usually, the model depends on how granular the data is. For equities, one of the most famous valuation models is the discounted cash flow model, popularly known as the DCF model. The crux of the model is as follows:

It gets into the specifics of every line item on the revenue and expenses side by trying to project their growth a few years later. In the end, it assumes a terminal growth rate and calculates the values for line items using the sum of an infinite arithmetic progression series.

It then goes into the free cash flow at the end of each year and for the terminal year.

It brings the calculations back to today by using the time value of money, usually known as discounting. This is the present value of the company based on its future cash flows.

Every line item you project into the future invites inaccuracies and questions about your growth numbers. The more broken down revenue and expense streams into several line items, the better the model. How you read between the lines of annual reports and the quarterly/yearly guidance the company provides determines the model's accuracy.

Price targets stemming from these models (or from any model) should be taken with a grain of salt because the exercise is more art than science, in my view. If you are interested, check out this video from Aswath Damodaran (one of my go-to valuation resources) to understand how complex it can get.

Using DCF for any of the projects in Web3 is difficult because we don’t have data sources that are granular enough. I imagine we can indulge in these models a few years/months out based on the work data sources like Token Terminal are doing.

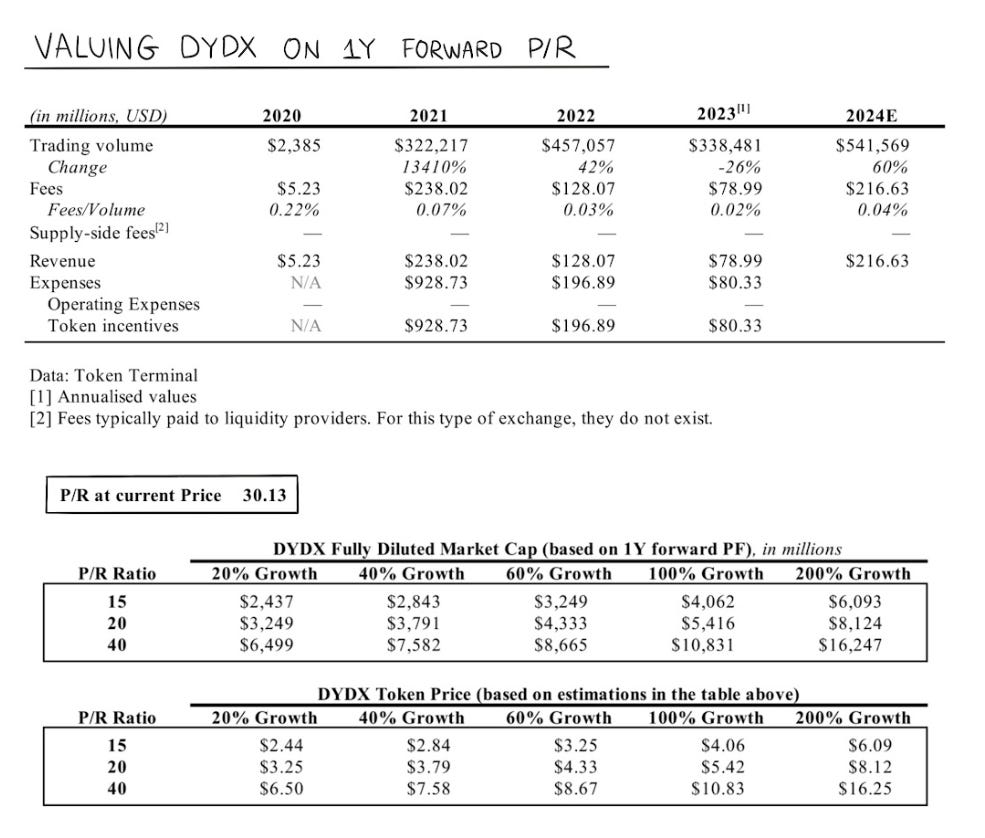

Anyway, the lack of revenue and expense line items to expand on meant I had to resort to a much simpler approach of using multiples. Since I’m valuing the DYDX token, I want to understand what the token holder gets for staking the token. So, I looked at the price-to-revenue multiple (P/R) at the end of 2024 using data from Token Terminal. The P/R ratio suggests how the market prices the exchange for every dollar of revenue going to token holders.

I annualised the numbers for 2023 and assumed different growth rates for the trading volume to arrive at the 2024 value. For example, the 60% change in the 2024E column assumes that the trading volume growth on dYdX is 60%.

The fees/volume number assumes the overall fees as a percentage of the volume. This is how I arrived at the fees for 2024.

dYdX intends to pass on all fees to stakers or validators. So, this becomes the revenue in question.

The second table shows different growth scenarios in point 1 – ranging from 20% to 200%. Naturally, the higher the growth, the higher the value.

In 2023, the price (the fully diluted market capitalisation) to the revenue multiple is 30.13. This number suggests how much premium the market places on revenue earned by dYdX. The second table shows the value based on three multiples – 15, 20, and 40. These are arbitrary numbers surrounding the current multiple.

The third table calculates the price per token by dividing the respective values in Table 2 by the total number of tokens.

I perform a similar exercise for GMX to understand how GMX fares against dYdX. Note that GMX fees get split into two parts – LPs (since GMX is based on AMM) and token holders. For a like-to-like comparison, I only consider the component routed to GMX token holders.

Another way to compare futures DEXs is to look at how much users are paying in fees to these platforms (either to LPs or to token holders) with respect to their fully diluted market capitalisation. Currently, DYDX has the highest PF ratio among the four leading futures DEXs. This means DYDX is more expensive than other DEXs. In other words, the market is attaching more value to the fees dYdX earns compared to its peers.

How does this compare to centralised finance (CeFi) exchanges? Coinbase has a revenue (a good proxy for DEX fees) of $2.58 billion with a market cap of $17.46 billion and a price-sales (P/S, analogous to the P/R or P/F ratio mentioned above) ratio of 6.76. A more established exchange, Nasdaq has a market cap of $24 billion against $4 billion in revenue, a P/S of 4.

As companies and industries mature, growth tends to taper off and become steady. Usually, the premium attached to revenue multiples arises from the fact that there’s room to grow. As DeFi and crypto are still early in their life cycles compared to more traditional companies, they naturally command a higher multiple in anticipation of growth.

Why is dYdX commanding a premium? There are a few reasons in my mind.

dYdX is the only perpetual futures DEX with order books. This means the exchange can afford the luxury of sharing all the revenue with token holders. In comparison, AMM-based DEXs have to share fees with the LPs. Token holders get a share of the fees at best.

Similar to Uniswap for spot trades, dYdX is an established brand for futures trading. The brand is an intangible asset that holds value.

The market is likely speculating on what is next for dYdX. I take a stab at this in the next section.

The Future

Recently, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) almost caught up to Binance regarding open interest (OI) on the Bitcoin futures. This is a good gauge of institutional interest. With the imminent Bitcoin ETF, this interest will likely grow. If 2021 is any guide, DEXs will be beneficiaries of the spillover into DeFi.

When dYdX launched a chain, they mentioned they were primarily focused on DeFi derivatives. With this new chain, dYdX is uniquely positioned to create a Deribit-like experience. dYdX already has perps based on order books. Assume they build options alongside perps with portfolio margin enabled for both perps and options. We will be looking at a DeFi-native alternative to Deribit. One that is more transparent and where no customers can be given special treatment, thus not allowing unknown counterparty, liquidity, and insolvency risks to creep into the system. Remember Alameda? We could avoid that disaster from happening yet again.

Aevo (Ribbon Finance) already has options and perps based on the off-chain order book. The product is similar to Deribit but lacks liquidity. Compared to dYdX’s 24H volume of $869 million and $309 million OI (open-interest), Aevo only has $5.7 million daily volume and $4.7 million OI. dYdX is already ~100X bigger.

Given Aevo’s capital efficiency (as it allows users to trade futures and options through the same capital), it may not need 100X OI to support 100X volume. At the moment, Aevo is a superior product but lacks liquidity. dYdX’s leading position depends on whether it can launch a suite of products to evolve into a derivatives ecosystem before Aevo manages to attract 100X liquidity.

Both dYdX and Aevo are independent app chains, allowing them to get more creative with how the token fits into their offerings. While dYdX is a Cosmos-based chain, Aevo is an Ethereum rollup. Both are in the early stages of developing their respective ecosystems.

If they are successful, are other successful applications like Uniswap also considering launching their chains? If yes, will it be as an L2 on Ethereum (like Aevo) or a completely independent chain? How does the bridging ecosystem evolve to enable a smooth flow of capital and information among these independent appchains?

These are just a few questions I’ve been thinking about since dYdX’s announcement, and I will write about them when I have answers.

Until next time,

Saurabh

If you liked reading this, check these out next: