The Embedded Economy

How Prediction Markets Will Change The Web

Friends, Romans, Countrymen (and people from the other 162 countries that read us),

I hope life is treating you well. And if it is not, I hope you find the strength to endure until the tides turn, because the laws of nature dictate that, with time, tides do turn.

Long-time readers of this publication may know that I am addicted to two things: the attention economy and markets. I’ve flirted with these themes in abundance here in the past. In Volatility as a Service, I argued that products offering volatility will hyperscale.

In Money Moves, I explained that crypto’s core promise is in moving money faster online.

In Culture, Capital and Crypto, I suggested that culture is a lever for taking crypto mainstream.

Today’s piece brings together these three ideas to lay a case for prediction markets. My argument is that the web is becoming boring. Creators serve algorithms and, in the process, destroy culture and capital formation. Prediction markets, as a primitive, offer an alternative. They are a mechanism to separate the art from the commercialisation of it. Stablecoins and agentic economies will fuel this shift.

Some housekeeping before we begin

If you enjoy reading this piece, please tag our brand handle here and let us know what you think. Our X account has been getting loads of love lately, and I’d like to keep that streak going. Share the article with your friends if you reading it. Be a menace. Cause chaos.

Also join our Telegram community here.If you have something mean to say, tag me instead. As always, if you are building on these primitives or thinking about how the web is evolving, drop us a note at venture@decentralised.co

Speaking of venture .. Sid will be in New York next week. He is due to meet several of our portfolio companies and meet some of our partners. We are scoping out hedge funds, exchanges and foundations we’d collaborate with going into 2026. If you are any of them, drop me a note as a response to this email and I’ll set you up.

Alright, let’s go.

Joel

Something is dying in my living room, and it stinks.

Its stench powers through the rug we try to hide it beneath, probably because the blood seeps through.

We call it the Internet.

The web used to work because the pool of attention within it has been ever-expanding. Between 2010 and 2025, nearly 2 billion people came online. However, that figure is now stagnating.

Founders who have built, scaled, and sold companies in Web2 were tapping into an ever-expanding resource. That of human attention. With each marginal person coming online and spending a third of their day looking at their bright screens, we had more of the same resources to mine for data. Gather enough data, and you can sell to individuals. The Internet is equal parts a machine for generating desire and for enabling commerce. Its cogwheels enable dissent, as much as the network powers collaboration.

Capture small slices of large enough transactions, and you have a trillion-dollar economy that runs on attention. This is the basis for the surveillance economy that exists today.

Where does the crisis emerge from? What is killing it?

There are three core parallel forces at play.

The constant consumption of content has created a marketplace with an abundant supply of attention but a lack of demand. Not all attention is worth the same. Is anyone famous at all when everyone has fifteen minutes of fame? What if those fifteen minutes were compressed into ten seconds? What use is attention if it does not drive intention? What if everyone is an anxious mess?

The expansion of AI-generated content means the human experience that once fuelled the creation of bits of work becomes redundant. Artists once tapped into pain, torment, hope, and desire. When you compress that into a few prompts, you create junk for the human mind. We may be trending towards peak obesity. The writing is on the wall. Meta released a social network primarily focused on AI-generated content, and OpenAI is also working on one.

The generation that came after the rise of Meta has lower literacy rates and higher rates of depression. If you think millennials have it better, consider that they live in an age with the highest number of single 40-year-olds. (Maybe, that’s a feature, not a bug - but I’ll leave that discussion for another time).A younger generation of net-izens is logging out of the web entirely. As the New York Times put it in this June essay, thinking is the new luxury good. Being constantly on the web is the new smoking. Logging in is not the same thing as being locked in.

In other words, between an abundance of supply (of content), decline (of attention), and a mental health epidemic, the web is undergoing a shift. Everybody is an influencer today. There needs to be filters, a content calendar, and an aesthetic that appeals to the audience. No performance is worth watching if everyone is performative. That means we will see a new web emerge. One that slowly unplugs from the zeitgeist and recreates a new form of expression.

These shifts in the attention economy are not new. Print media took power from the scribes and priests of ages past and gave it to the writer. That medium, in turn, was consumed as the Internet empowered individuals to build an audience from home—a privilege once held by newspapers. Niche, isolated blogs were eaten alive by large social networks that condensed networks of people. Remember WordPress? How about Tumblr?

Now, as we trend towards peak social media, we may be seeing a resurgence of long-form written content as people grow tired of constant entertainment.

The hedonic treadmill of human attention keeps us moving—and it appears we have walked our way to new shores.

Today’s piece explores how it may arrive.

The basis for my thesis is three core points.

Advertisements powered the web because we did not have mechanisms to pay for when the Internet came along. Most individuals did not have debit cards or bank accounts in the early 2000s. Businesses relied on capturing eyeballs, as wallets were not yet online.

Much of the “value” on the internet emerges from transactions. As our transaction systems evolve—owing to stablecoins and primitives like single-sign-on wallets (e.g., Privy or Para) —we will see more transaction-enabled business models emerge in consumer-facing segments like social networks.

There will be a new crop of businesses that are built on this shift from the attention economy to the transaction economy.

Knowingly or unknowingly, those working in Web3 social networks and payment systems have built the Lego blocks that could breathe new life back into the internet. This piece is my attempt at putting them together.

Weapons of Mass Distraction

Apple’s scan-and-pay and Amazon’s one-click checkout buttons tap into the same psyche—that of human impulse. When making a payment becomes frictionless, we think little of the effort needed to earn that money.

Humans tend to spend more when we do not pay in physical cash. Did the switch from physical, handwritten notes to text messaging have a similar impact? Tapping away an emoji simply does not compare to finding the words needed to capture an emotion.

Our monkey brains have had less than four centuries of physical cash to interact with. In agrarian societies, value transfer often involved labour. You do not go around offering milk to everyone in the village if you must protect the cow and ensure it is well fed. You do it for friendly neighbours as an act of love.

We live in a world that is separate from the labour required to generate value. It is a beautiful thing because I do not want to go back up the hills my grandparents once toiled in. It is also a psychological blind spot that one should be aware of. The easier a transaction is, the less we understand the risks & variables involved. This is the reason why so many in crypto lose their money to leverage.

The lack of friction in taking absurd amounts of risk is equal parts a bug and a feature.

In the early 2000s, platforms had very few mechanisms for tracing attention to the transaction it produced. If I saw an advertisement for an iPod on the web in the 2000s, and asked my dad to buy it for me on his way back from UK, the platform showing me the advertisement would have no way of tracking that transaction. (India had strict restrictions on gadget imports, and this is how I got my first iPod nano like many teenagers at the time)

This division between content consumption and transaction traceability was a key issue as the web evolved. Ad-attributions helped fix that by the early 2010s. This podcast episode, which we did with Antonio Martinez, explains how it came to be. I recommend reading his book Chaos Monkeys for context on attribution systems.

Cookies have enabled tracking of transactions across platforms since at least the early 2010s. You could see a post on Facebook, have an ad from Google, and make a purchase on Amazon - and attribution systems that track how that purchase happened have evolved sufficiently to track a user’s journey. Advertisers knew that the trick to making a purchase happen is to repeatedly show a user similar content to generate desire, and that is why the web reinforces our views.

We tend to see the same things repeatedly once the algorithm detects preferences.

Platforms like Twitch took this one step further by allowing users to buy sticker packs and tip directly. In the process, we created a creator economy where a creator’s ability to hold attention became the product.

The creator economy, in its current form, is socialism without the benefits.

The audience enjoys the content, the platform owns the audience, and the creator must keep producing to stay relevant. The serfs serve the algorithms in the modern day.

As a generation finds itself stuck in bullshit jobs, more people are turning to digital platforms to find gigs and sustain themselves, and that is a beautiful thing. More people should be able to tap into their own creativity to find meaning, community, and a livelihood. However, the underlying infrastructure may not be able to sustain it. Creators are incentivised to tap into the algorithm for reach. One risks replacing the torment of living in a cubicle with the pain of serving an algorithm.

It’s like we try to take food fresh out the frying pan into the fire.

The web needs a better way to monetise itself. What we see with experiments in creator economies, prediction markets, and whatever the kind folks at Zora are trying—are early primitives that aim to address these issues. Can an individual make a living with a small subset of audience without catering to the incentives of a platform or competing with other creators?

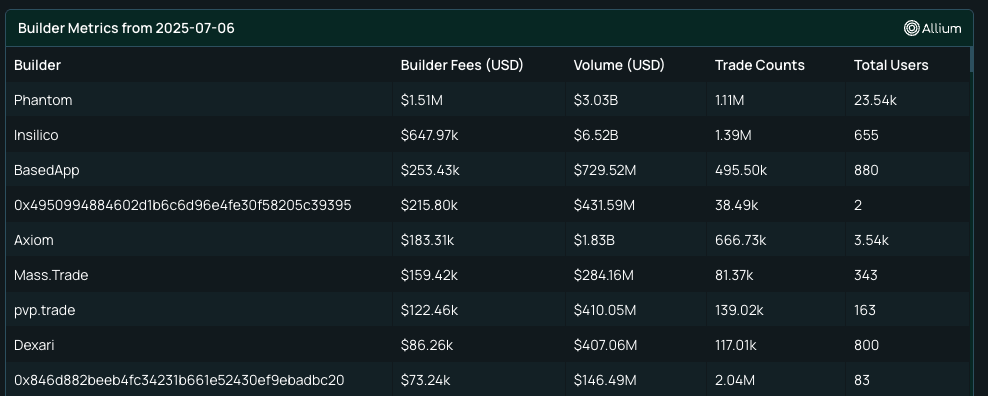

We saw an early instance of what this could look like with crypto debit cards and wallets. Over the past month, we saw Phantom, Rainbow, Kast, and Based integrate Hyperliquid’s perpetuals into their products. Unbeknownst to the world, a slight shift had occurred. Instead of powering products through ads, these wallets were now monetising themselves through transaction fees on a hyper-financialised product.

Both Kast and Based are debit card issuers—why would they integrate perpetuals? They did it because that is how you increase a user’s lifetime value (LTV). Consider the numbers below. Both Based and Phantom make six figures in revenue from less than thousand active users on their Hyperliquid integration

The integration of perpetuals into these wallets is a sign of what is to come. It is the emergence of markets in our feeds. We are witnessing the real-time compression of the time it takes for attention to become a transaction. Don’t believe me?

Consider oracle by $noice. It allows users to buy an asset with a single click. In fact, the button does not even need to be on a third-party platform. You simply like a tweet with a cash tag, and the agent automatically buys it for you. The transaction happens with a single click, and the cost is less than $0.01. It is a primitive version of what the future of social networks could look like. There is much to be said about the product, but here’s what stands out.

It allows a person to transfer value to a third party through an interaction we are very accustomed to: a Twitter-like one. No signing transactions, no wallet refreshes, no bridging. Just the click of a button. Why is this unique?

Farcaster Frames are an incredible primitive, but they require a separate social graph, which is still in its infancy. Platforms like Twitter already have the users. Enabling transactions via an embedded API lets you tap into the Twitter social graph without requiring users to leave Twitter.

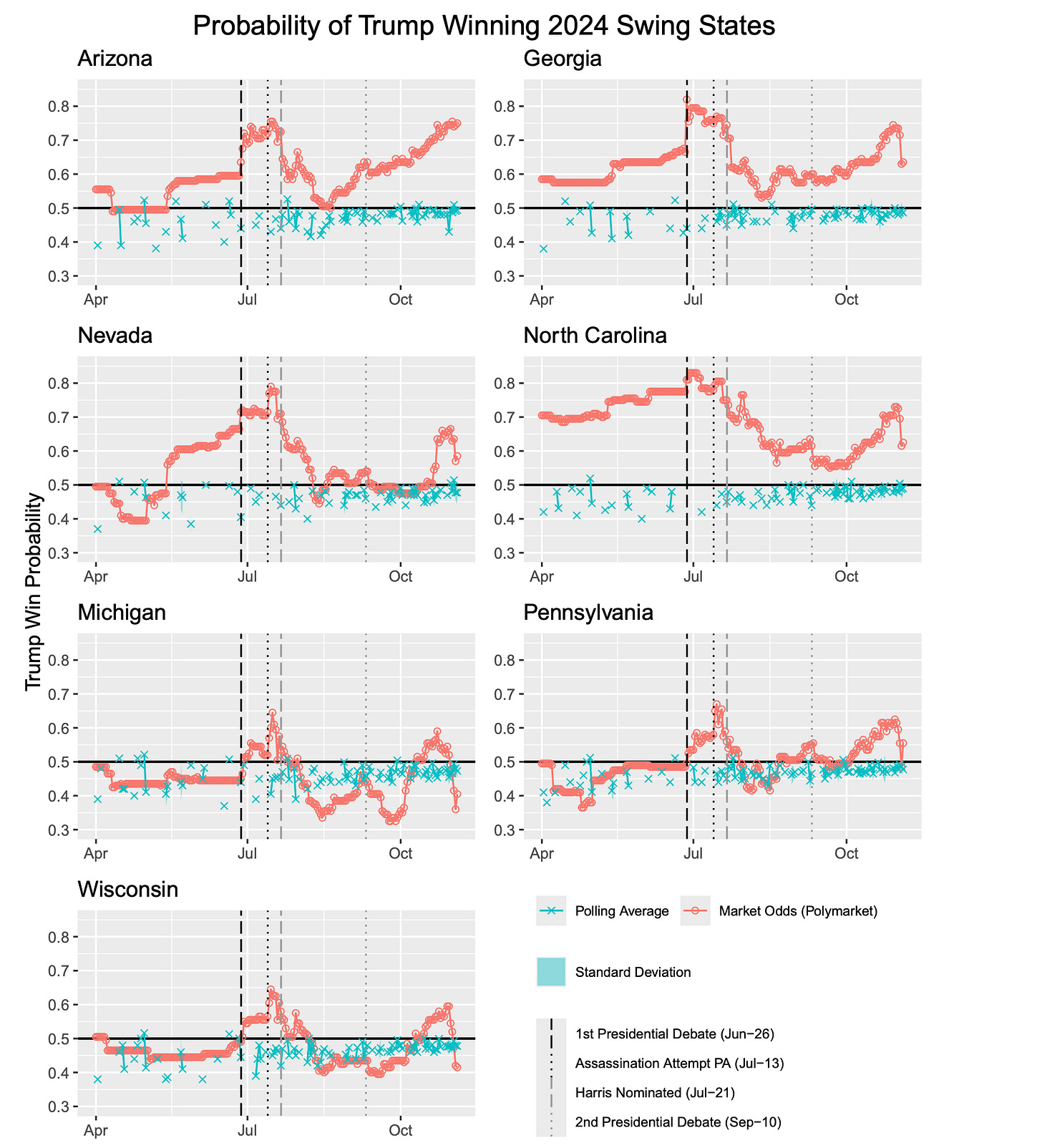

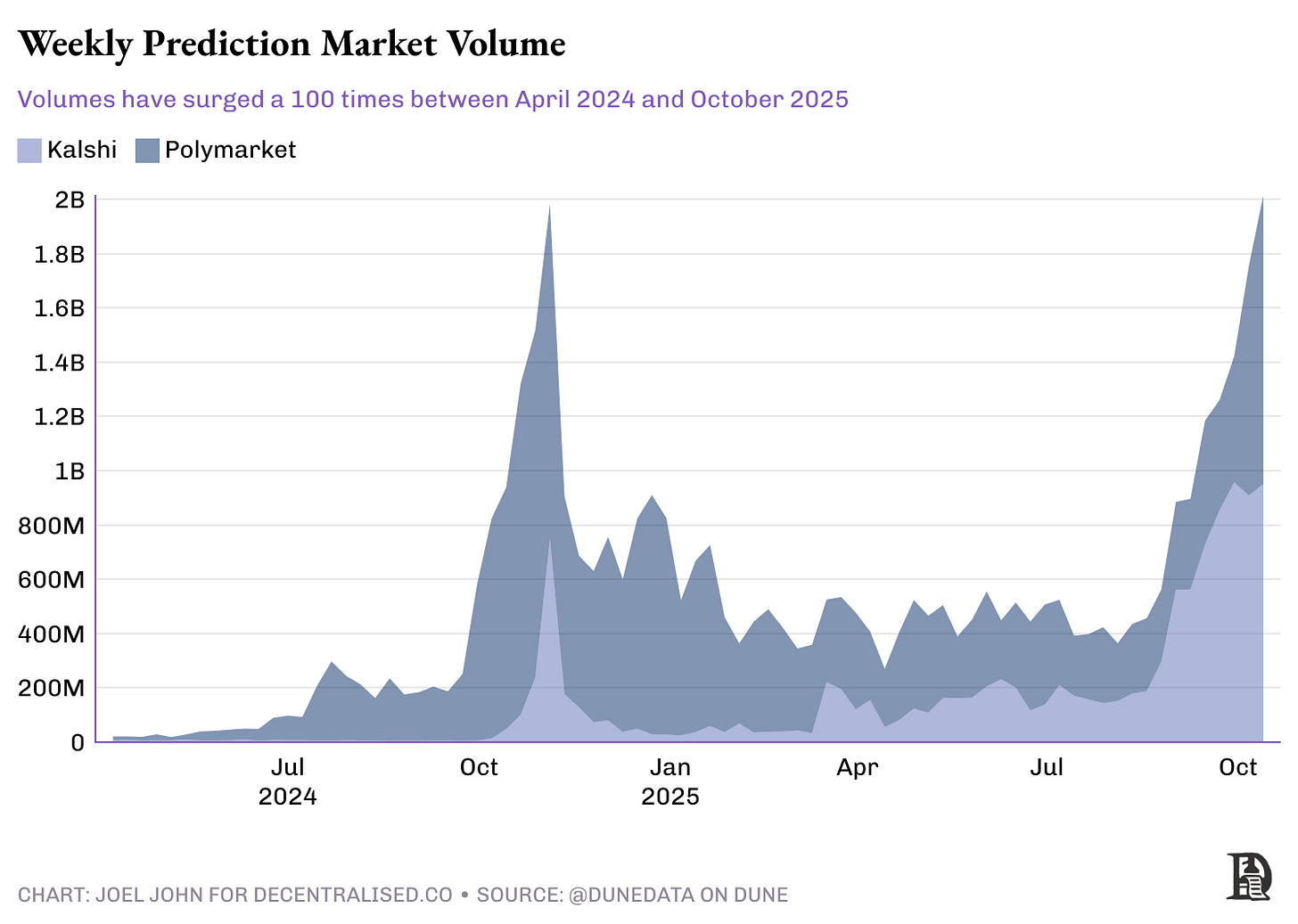

Twitter understands the shift that is coming its way quite well. In June, there was a move to embed prediction markets within it. It has been months since, and X has not enabled it, but prediction markets have taken off on their own. Consider the two charts below. As late as April 2024, weekly volume on prediction markets was around $20 million. As of October 2025, that figure is close to $2 billion—each week! These markets see over 6 million transactions each week, so the average bet size is around $300.

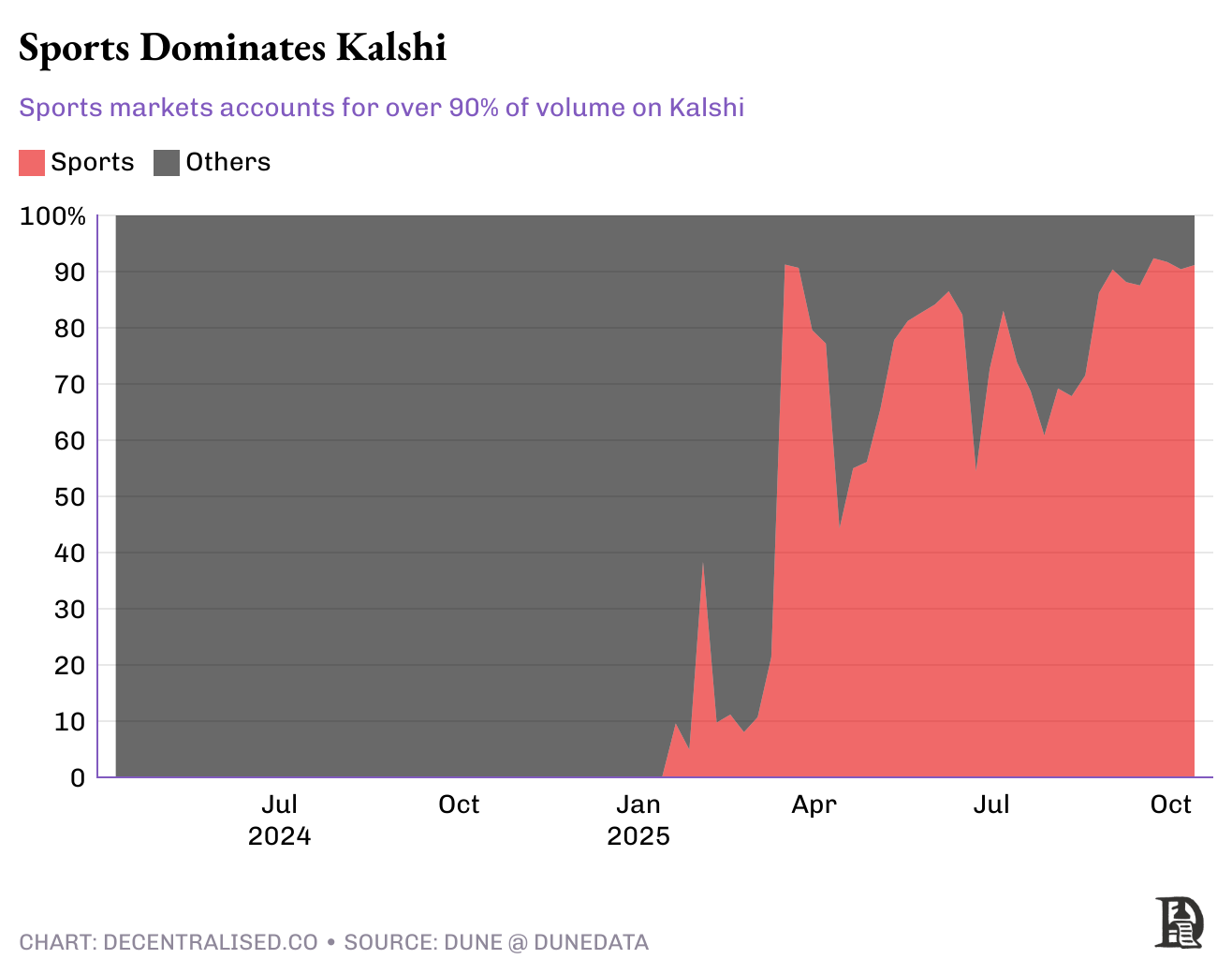

Of some $950 million in bets placed on Kalshi, $877 million is for sports. One-third of all betting volume on Polymarket comes from the same category. Compared to the 1,030 users Polymarket had in April of 2025, the product commanded close to 150k users last week. In other words, we are seeing a rise in on-chain embedded markets that draw on culture.

Markets are pricing this transition efficiently. Facebook had close to 360 million users when it raised $200 million at a $10 billion valuation. Inflation-adjusted, that figure would be $15 billion today. Contrast that with Polymarket being valued $9 billion in a recent round led by the owners of the New York Stock Exchange.

This contrast captures how the web is evolving from one of attention to that of transactions.

Gaming economies have already seen this shift. They serve the same purpose as social networks do. Firstly, they offer a meaningful distraction. Secondly, they create a sense of community. Thirdly, they sell digital goods. Gaming economies like the one in Roblox are large-scale transaction products packaged as entertainment goods. Roblox sees approximately 111 million DAUs. Collectively, they spend ±27 billion human hours in those economies.

Why? Because, unlike meme coins, these markets have a sense of fairness to them, and the rate of value destruction is not as rapid. A meme coin has a community only as long as the numbers trend upwards. Gaming economies, in contrast, have lindy effects and sustain far longer.

Prediction markets are a new primitive with both elements. Large whales, or insiders, may not necessarily have an edge without undermining the platform’s integrity. Users usually know the range of possible outcomes. So, we are at this juncture where products (with relative distribution) try to embed these primitives to increase the lifetime value of individual users while reducing their own acquisition costs.

Crypto’s current rush to integrate perpetuals, prediction markets, on-chain stocks & cultural goods (like sports markets or Pokemon cards) is the industry’s expansion to the mainstream. How does this affect our brethren toiling in the digital farms? The serfs I addressed as creators a while back?

One way creator economies will evolve is by empowering creators to have their own markets. Do you think President Trump will visit China next month? A creator could embed a polymarket into the piece of content and earn from individuals trading on their analysis. The challenge is that when the medium of expression requires a transaction to be relevant, we will shift the nature of the conversations we have. There will be “influencers” whose value will be determined by their ability to create a market. What happens to art? Who speaks for stories?

What is the value of a wall of text that keeps someone from engaging in self-harm?

Do we really need a prediction market to value it?

I don’t know the answer to that yet, but it helps to have a view of how the market landscape itself is evolving.

How Much for Truth?

Human existence is an ongoing endeavour to find the truth. Philosophy asks what the point of life is. Biology seeks to understand how life happens. Maths asks how long this show lasts. Poetry and the arts keep us entertained while life happens. The truth is subjective, and, for all intents and purposes, markets are among the most potent tools (apart from science) to help us reach agreement on what the truth is. Blockchain rails, being money rails, mean we can now price what the truth is at a global scale.

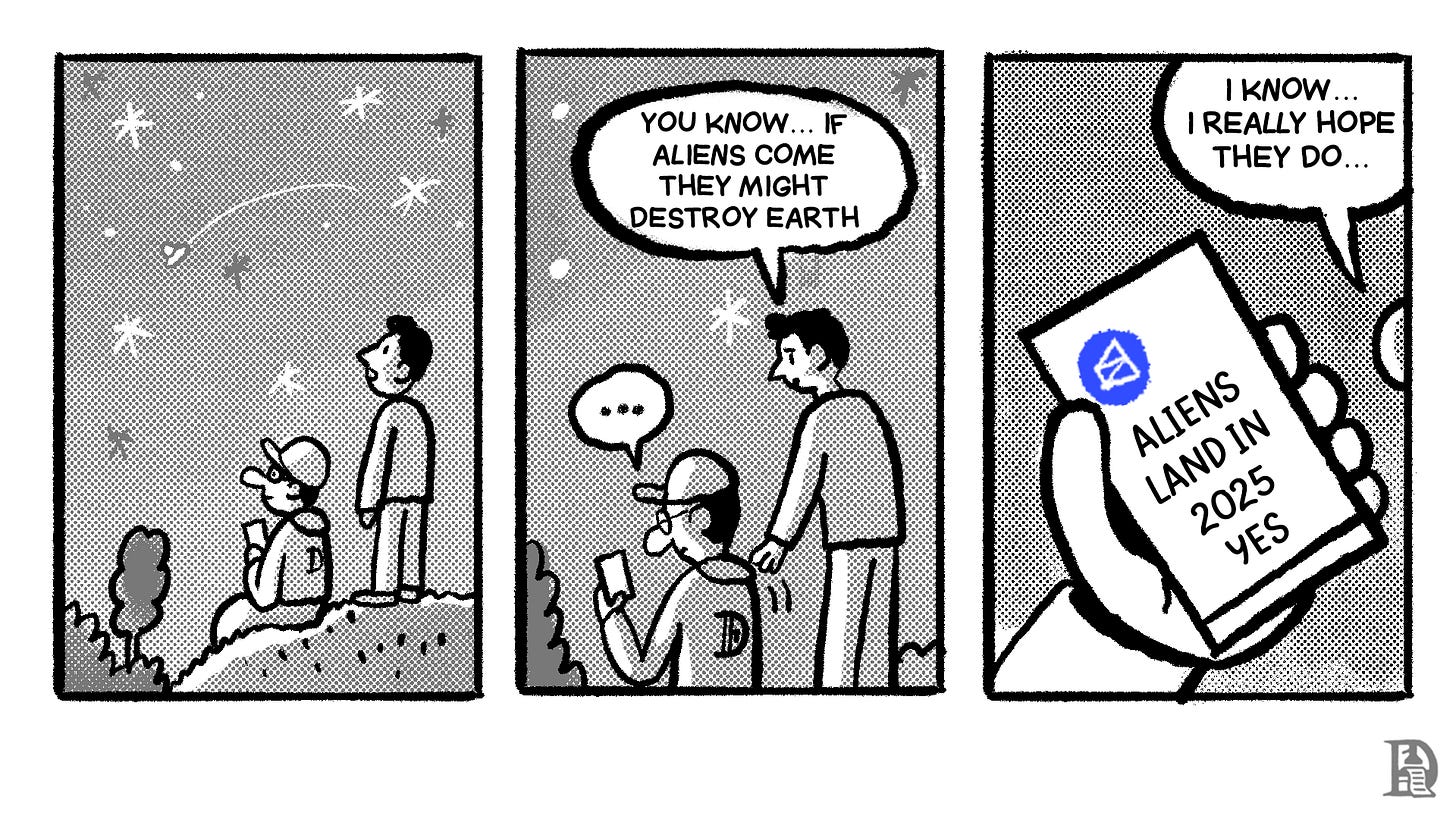

Do you think Donald Trump will tweet covfefe again? You can bet on it. In fact, primitives like Liquid allow you to spin up a chat and bet with friends on anything. You could bet on whether a person would lose weight, find the love of their life, or finish a pending draft, so long as you have an oracle to verify the truth. The exact mechanics of how it works are not of interest (for today), but what we have are primitives for two things.

The ability to spin up a market for anything

For the value to be settled and distributed across the world.

Collectively, they allow opinions to be priced, traded, and settled globally. This is like when blogs allowed thought to be transmuted across the globe. Except, instead of isolated opinions, we have markets.

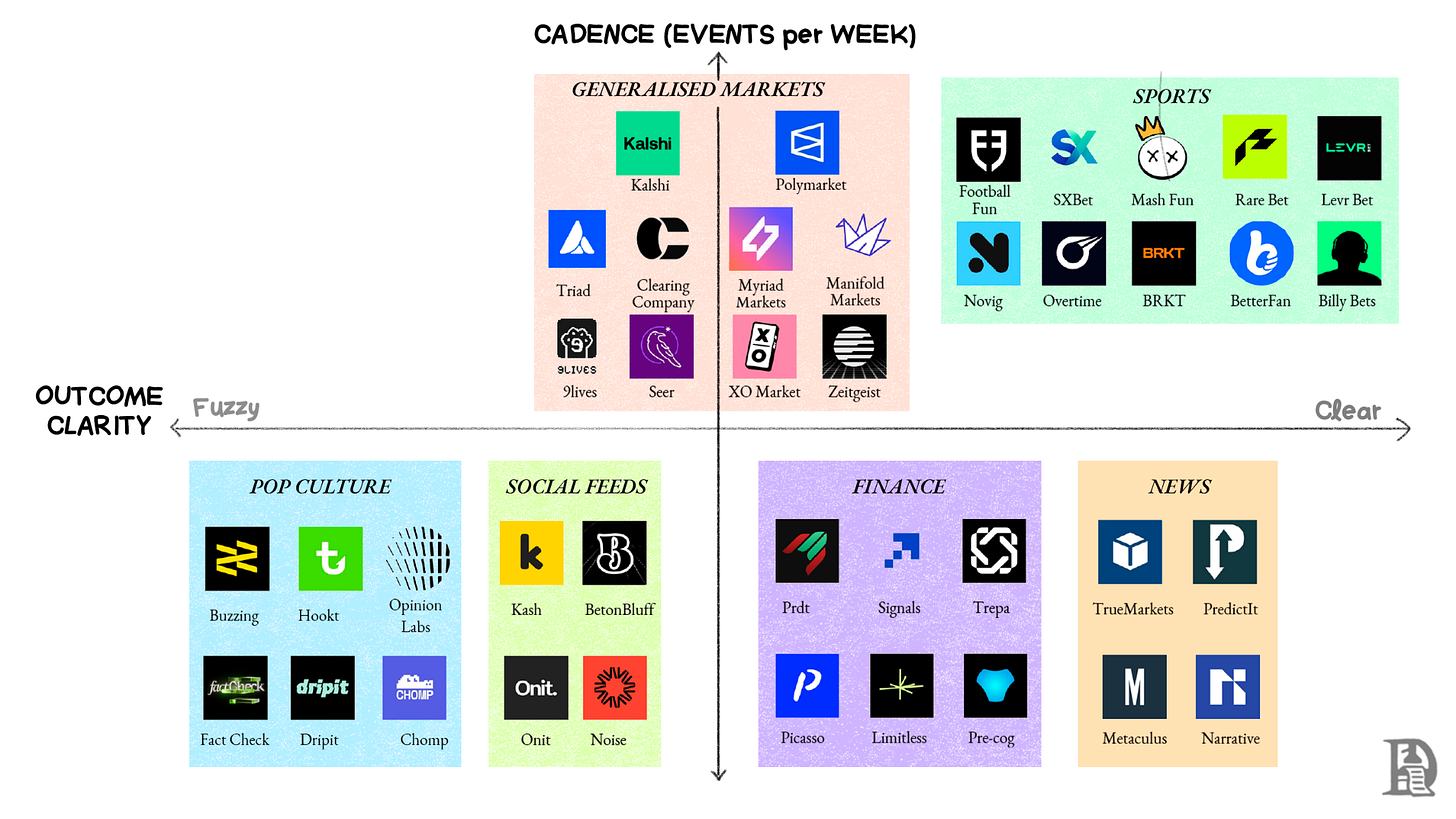

How then would the market evolve? This is akin to asking what the broad spectrum of blogs or individual pages will be. If money becomes a medium of expression, then the nature of markets will cover the breadth and depth of human interests. Consider the market map above for context. Broadly, markets can be divided by the frequency with which an event is resolved and the clarity of the outcome.

Most markets have clear outcomes. We no longer argue about Donald Trump being the President of the United States. Some markets, however, can be subjective. For instance, a market on whether J Cole is better than Kendick Lamar may be resolved based on popularity. Maybe Kendrick’s fans are vocal about his lyricism and spam aggressively in any way possible.

My point is that on-chain prediction markets will evolve to either reach consensus or seek objective truth, and we need both. Most products we see in pop culture and “sentiment” gathering are fuzzy about how the outcomes will be. Markets that orient towards sports, politics, and markets will have clear outcomes.

Democracies, for instance, are consensus-seeking machines. People voting for the losing party may see nothing.

Many markets that look at fuzzy outcomes have what can be called binary markets. You either win a dollar or lose the entirety of the bet you placed. The game theory here is interesting. Market participants are not just voting on what they think is right. They are betting on what everyone else thinks is right. Effectively, it forces individuals to “buy” into a position because they have capital incentives for doing so.

My thesis is that when these incentives scale, as they often do, the nature of our conversations and interactions on the Internet will shift from a focus on virality to one that enables transactions.

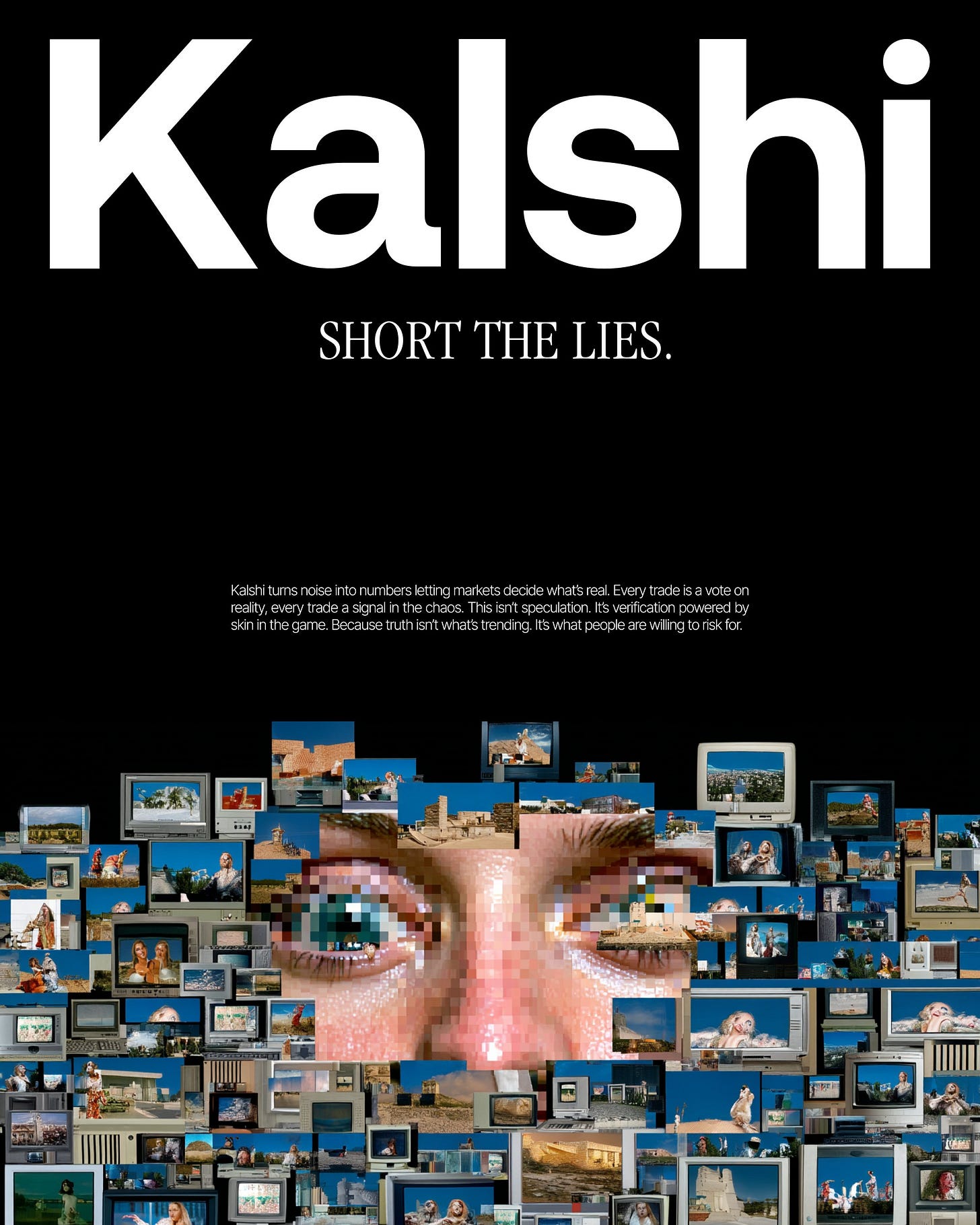

Platforms like Manifold and Zeitgeist use user social activity, such as posts under a market, to determine whether it should be trending. Popularity contests, on their own, are not interesting to us. However, they can find the truth in ways most other primitives have not been able to. Prediction markets like Polymarket have consistently beaten polling as a mechanism to surface the odds of a possibility like Donald Trump winning a swing state. In fact, while researching for this piece, I came across a paper by the United States Military exploring the use of prediction markets to assess security threats.

This is where this transition gets interesting. We tend to think crypto is all about speculation. However, that is akin to believing the Internet is all about pornography. By some estimates, it was the case. In the early 1990s, much of the Internet’s bandwidth and revenue came from adult content. However, market forces and capital incentives structured the attention economy that powers Meta, Alphabet, and a myriad of other internet monopolies in the decade that followed.

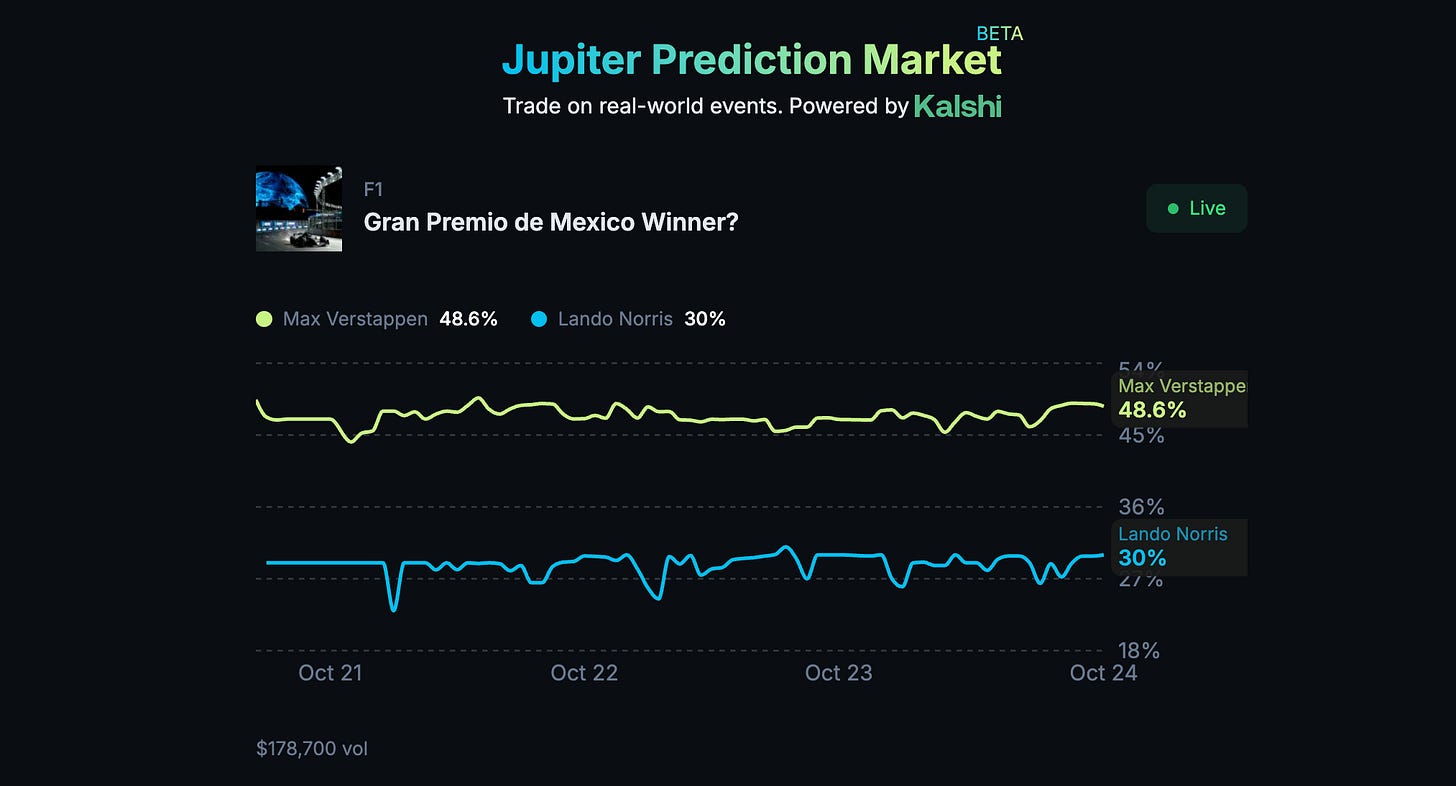

Crypto struggles to remain relevant to the average internet user. People do not wake up thinking about the TPS of an L2 or how the validators of a network went down with AWS. They do care about sports, music, and politics. Embedded prediction markets blur the line between social attention and on-chain transactions for the average individual. This is why prediction markets matter as a category for the industry.

All Content. No Contentment.

Embedded markets are one of the business models the Internet may embrace as a primitive to power content of all forms. In a hypothetical future, all exchanges (like Coinbase or Nasdaq) will be content platforms, and all content platforms will, in turn, be exchanges. Retail speculation in meme assets and derivatives is a symbol of late-stage internet. People gather on platforms like Reddit, X, and Telegram partly because of the capital incentives at play.

If that is indeed the world we are trending towards, then the lines will blur between financial platforms and social networks. The lines between our wallets and minds will blur. Coinbase’s recent acquisition of UpOnly and Echo is a predecessor to this switch. The owners of the NYSE probably understand that the alternative to Google’s ad marketplace is a prediction market.

Creating as a human in the age of AI slop will require incentives.

Embedded markets are one way of doing it.

As of today, prediction markets are trying to be both the product and the distribution. They build the venue, then spend the rest of their energy dragging attention back to it—screenshotted odds on X, quote-tweets from power users, Discord bots piping prices into chats. It works in bursts because a live market is inherently shareable. Discovery happens off-platform, intent dies in the tab hop, and the product starts optimising for virality (“markets that screenshot well”) instead of truth (tight rules, fast settlement).

Embedding decouples those roles. The market stays the product; existing media becomes the distribution. Prediction markets improve the two things media struggles with most: credibility and usefulness. They turn a claim into an object—a live probability with rules, sources, and a resolution clock. Instead of hedged paragraphs and selective quotes, a story carries a number that updates as facts land and settles when reality arrives. That shift makes coverage falsifiable in public. Readers aren’t just consuming takes; they watch beliefs priced and resolved with receipts.

Embedding is how this upgrade reaches people where attention already lives. Odds under a headline remove the tab-hop that kills intent. A policy piece with a belief sparkline attached turns “he said, she said” into “here’s where the price moved and why.”

Newsrooms get a credibility layer and a new line item: even modest conversion outperforms another ad slot because value is anchored to action, not impressions. If two out of every hundred readers place a single $15 trade, a 2% fee yields roughly $6 per thousand views, beating CPMs and far more aligned with the story. Creators trade outrage for calibration; a visible track record becomes a balance sheet they can carry across posts, and rev-share on embedded flow beats chasing the next viral rant.

This is why Polymarket is working on Embedding toolkits - making it easy to reference odds on any social media platform. Substack and X both support embeds, allowing writers to augment their reporting with odds. Writers like Matt Levine reference odds in their stories, browsers like Perplexity display odds as search results, and news portals like Axios use Polymarket charts to support their stories.

Reporting Live … From an LLM

So far, we have explored how humans will rally around events to trade them. Markets sustain only when they trend towards efficiency. When buyers or sellers engage in a transaction, they are either predicting the future probability of a price rise or a price dip. How will embedded markets become more efficient if nobody is market-making them? Sophisticated hedge funds do not have enough liquidity in these markets today to bother with them.

Currently, agents do a good job at aggregating information. Internally, we use Kaito and AskSurf to find relevant bits of media for our own consumption. Large news outlets have simultaneously integrated AI into their products to make content easier to consume or to aggregate information more easily. For instance, a good way to review our own writing is to use ChatGPT and ask it a query like “show me all Decentralised.co’s writing on revenue”. What if you could use agents to trade?

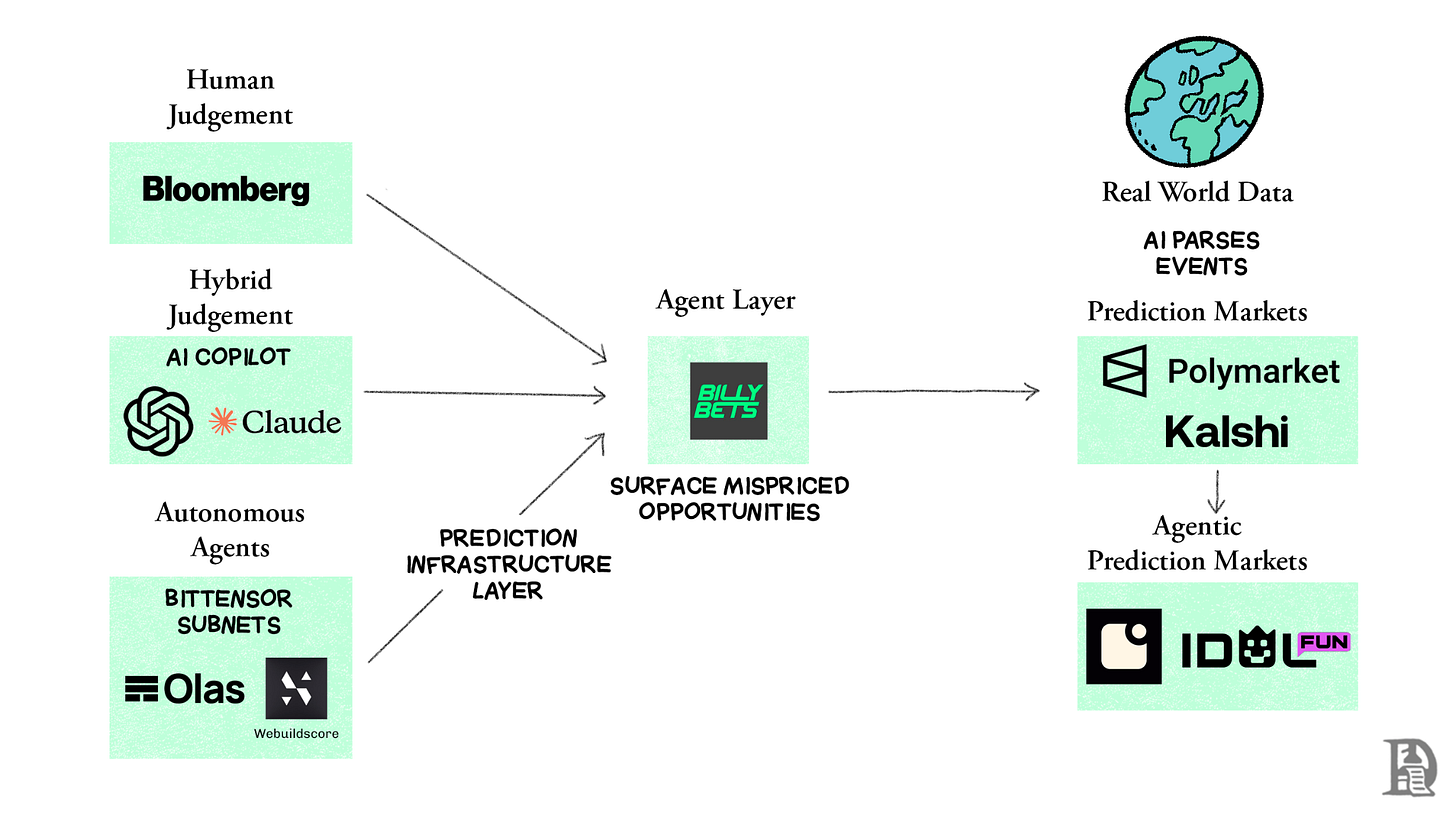

Our thinking is that agentic systems will play a key role in providing liquidity and conducting trades as prediction markets come of age. Currently, bots scan YouTube transcriptions of key events, such as Jerome Powell’s speeches, to take positions. In the future, we will see a mix of real-time media, prediction markets, and agents collaborating to surface more accurate information.

In fact, there are many ways agents can interact with prediction markets.

Human judgment - Political analysts and sports bettors read through magazines like Bloomberg and watch matches to get an intuition of what’s going to happen in the future. The key here is to stay highly informed, watch insightful commentators to sharpen your own knowledge, and apply it in PMs.

Hybrid Judgment - Analysts using AI to gather information, double-check their probabilities, and come here. Users can just talk to their preferred LLM. Some teams are developing specialised co-pilots that can help users make the right calls. On Billybets, you can select how much bankroll you have and what type of strategy you prefer. Billybets will make the bets for you depending on your choice.

Autonomous agents - Self-optimising AI systems that compete to generate the best signals. Networks like Bittensor and Olas have birthed subnets—Score, Zeus, Mantis —each specialising in a specific domain: sports, weather, macro. They work like evolutionary quant desks: thousands of models predicting outcomes, reweighted every time reality proves them right or wrong. Webuildscore uses sports video and statistics to train models that predict outcomes faster than bookmakers.

Aggregation Layer - Use AI to spot mispriced opportunities across different prediction markets. Agents can instantly send liquidity to mispriced markets. If a sports bet on Kalshi is priced at ManUnited 60% while every other prediction market is at 40%, the AI agent places a bet against ManU on Kalshi.

Agentic Prediction Markets -These are markets about markets, where autonomous agents themselves become the subject of prediction. In Fraction AI, agents trade with $100k virtual bankrolls, and humans bet on which agent will outperform. The market becomes a scoreboard for intelligence.

In fact, there is a live market where agents bet on one another’s performance, and you can see it here. It is an interesting look at how crypto-native primitives interact with AI agents and the market. What if an individual wanted to customise an agent that traded on their behalf? What if someone believed in chaos and wanted to short every market related to a particular politician? Or wanted to go optimistically long on a musician of their preference? You need tooling that consumes information and takes a position on your behalf, often with limited capital.

Talus is working on this last section of Agentic Prediction Markets. Their Nexus platform enables anyone to quickly spin up AI agents on-chain. According to them, AI agents will be used across prediction markets because they combine two traits that agents thrive on - information density and price sensitivity. It’s a high-frequency information environment where edges appear and vanish in minutes. Human forecasters simply can’t monitor thousands of events across politics, sports, and macro data simultaneously.

AI agents, by contrast, can parse hundreds of feeds, extract latent correlations, and react the moment a signal shifts. You can read about how it works in the Nexus documentation here.

Agents can provide both context and liquidity when pricing an event. This turns the bickering and fighting on social media platforms into measurable odds. It also reduces the amount of data needed to form an opinion to a single number. Whether this is the best way to make a decision remains to be seen, but if the agentic web does take off, prediction markets will play a key role.

The Social Paradox

I’ve been reading the Social Paradox by William Hippel over the past few weeks. It is an interesting read on how humans need to balance autonomy with reliance on one another. Leave a person alone too long, and they may (quite literally) wither away and die. Force them into crowds, and they may lose their sense of self. Most of balancing healthy relationships is respecting this need for connection and autonomy.

A version of this extends to our information appetite, too. We’d love to know what our friends are up to or share the random bits of art we created. That tendency is what got us on the web in the first place. Being bombarded with information we did not ask for leads to mental exhaustion. Modern workplaces require us to be plugged in and constantly consume information. So, most of us are probably never going to fully log off. In fact, some books argue that we are at the end of the human experience. All of us are mere zombies plugged into networks of information running an economy we did not sign up for.

Are prediction markets the fix? Not really. Prediction markets, and specifically embedded ones, are a gradual evolution of the web’s economy. Between agents, stablecoins, and composable markets, we are trending toward a world where all bits of information can be priced in for reliance. This should mean we trend towards a society where fake news declines and hyperbole does not rise. Creators will have to create fewer bits of content, and individuals will be able to have the weight of capital markets behind the views they consume. It is a step forward.

At the same time, most things worth consuming may never be monetised. Commerce has the beautiful ability to amplify something and make it worse at the same time. Most works of human art worth consuming were not created with mass-market distribution in mind. They were created to escape or to express. Sometimes, both. Would Shakespeare’s work be better off with a prediction market for what happens to Romeo and Juliet? I don’t know. Maybe Romeo would have a view on it.

As exciting as prediction markets are, there will be pockets of our attention that resist commercialisation. We don’t run ads in handwritten notes written for a loved one for instance.

In the words of a philosopher that I’ve come to like lately - freedom is often found in the space between stimulus and response. Not all bits of media will inspire a transaction. Not all forms of art require pricing. You can already see this diversion on the Internet. On Twitter, people optimise for viral hooks. On Substack, people speak their mind because they already have a relationship with the end user through mailing lists. Close-knit communities are the resistance to the rapid, relentless march of the modern-day attention-economy behemoths.

How will this dynamic evolve as prediction markets embed in media?

I don’t know, but for now, here’s what’s evident. The primitives for the next step in the attention economy are here. We are witnessing the birth of the transaction economy.

Embedding (in) Markets,

Joel

The creator economy is indentured servitude. They farm the land but they can’t own it

will transactions become a form of acceptable expression? in many ways, it is true even today in the physical world. will it be amplified? on steroids on the internet that moves money at speed with disdain for the old financial walls and geographical boundaries.