Culture, Capital & Crypto

Michelangelo, Jay-Z and Jamie Dimon walk into a bar..

Hey there

A newsletter is two things. It is the news and a letter. We have done a fairly good job at the former with our breakdowns of business models within crypto over the past few months. Today, I want to do the latter. Write you guys a letter.

A person I consider very dear told me recently that sometimes the most radical thing you can do is speak plainly about complex feelings instead of turning it into a manifesto. So that is what I (try to) do in today’s issue. I take the mic, keyboard, from my fellow writers to talk about what it may take to scale crypto 100 times from here. I may have still written up a manifesto, though.

In particular, I explain how culture within crypto would evolve as we go from niche technology to one that powers the world’s financial rails and what that means for people that have been early to the industry. The story today involves Michelangelo, Hyperliquid, and song recommendations from Pakistan. Strange mix, I know. Which reminds me…

If you are building apps that explore how culture is formed, distributed or consumed, drop us a note at venture@decentralised.co. DCo works with a powerful network of capital allocators, collaborations with multiple growth-stage protocols, and an underlying research engine that powers our writing. We could probably help.

Lastly, if you enjoyed reading this, do tag the brand handle (@decentralisedco) and let us know what you think. The dopamine hit helps.

On to the story now.

TL:DR - Crypto stands the risk of being a hyperfinancialised ecosystem that struggles to scale past its infancy. The next generation of products that scale will have transactions being a small part of its feature subsets.

For Web3 apps to scale, we will need to start building products that keep people coming back for reasons that don’t involve a transaction. Much like only 1% of the internet posts, there may be a future where only 1% of users transact in a web3 native app. Crypto is a culture and a medium of expression. Founders will need to focus on both if we are to scale the industry. I lay the case for why ..

I often think about what went through Michelangelo’s mind as he painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. It is one of the finest pieces of art in human history. Initially, he wanted nothing to do with it. Michelangelo’s art was in sculpting marble. Hammer. Stone. The human form. That was his playground.

He was in debt for the non-delivery of sculptures for the grave of a late Pope when he received the assignment. Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo to paint the fresco of the chapel. Michelangelo thought this was a plot by his competitors to make him look stupid, as the project was challenging to complete. He was in a difficult situation, stuck between a dead Pope and a living one’s commissions.

Back then, I presume one could not just walk up to the head of the Catholic Church and say no. So, he accepted the commission and spent four years painting a ceiling between 1508 and 1512. He hated the commission so much that he wrote a poem in which he described himself as a hunched-up cat. The specific bit that often captures my attention is these words in his poem.

My painting is dead.

Defend it for me, Giovanni, protect my honour.

I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.

None of this may be to anyone who commits their life to art. Delayed deadlines. Doing work that is different from what one wants to do. And, of course, the questioning of one’s self-worth. Keep in mind, however, the man was creating culture and history as he said, “I am not a painter”.

Do you see the name mentioned in that poem? Giovanni? That refers to Giovanni Giovanni da Pistoia. But there’s a different Giovanni that’s relevant for us. It is Giovanni Medici. He was a childhood friend of Michelangelo. They grew up together. Michelangelo was taken to the Medici Riccardi Palace as a teenager under the patronage of Lorenzo Medici.

The Medici were a prominent banking family in medieval Europe. Think of them as the fifteenth-century equivalent of JP Morgan, or SoftBank. Except these guys were the financial architects of the Renaissance itself—the Godfathers of the game.

I sit here writing about Michelangelo, 520 years after his paintings were completed, partly because some of the most prominent bankers of the time were behind him. Throughout time, capital, or money, flirts with art to create what we consider culture. Most pieces of art society admires have had a heavy infusion of capital behind them. Michelangelo may not have been the best artist of his time.

There may be countless artists who capture human emotions better littered over time, but we know little of them. Partly, because they were never in the inner circle of where capital resides. Partly because some artists keep their best work unpublished in saved drafts. (Please publish!)

This gets even more interesting when you consider how modern media works. The Sistine Chapels of our age are not in Europe: they are on the Internet. You log into them every day on X, Instagram, and Substack. The Michelangelos of our time are not waiting for the blessings of the Medici. However, they do hope the algorithms play in their favour. The Medicis’ of the modern world acquire the chapel and slap their faces on it. Elon Musk boosted the number of views he gets on his posts on X in the months following the acquisition of the platform. The new Gods build their chapels.

Technology can increase the pace at which culture can be changed. Memes are legos for building culture in the age of nine-second videos. It also relies on capital to scale. We would not be talking of platforms like Facebook if it weren’t for the billions of dollars that went into funding them, and the regulations that protected its founders from being jailed for what’s posted on there. Imagine being able to sue Zuckerberg for the racist memes your distant uncle posts on a Friday night.

Technologies are levers for changing culture today, as they scale how humans express themselves. All technologies leave an imprint on culture as they change the mediums with which people express.

I have been thinking about how technology, culture and capital blend over time. As a technology scales, it attracts capital. In the process of doing so, the technology tones down how it expresses itself. Instead of arguing for radical decentralisation, we have, for instance, been talking about better unit economics within crypto. Instead of talking about how banks are evil, we now hail how they distribute digital assets. This transition intrigues me. It affects everything from how founders pitch to how CMOs define stories.

But before we go there, let’s take a quick walk down the evolution of media itself.

Evolution

Man is a machine of expression. Right from the moment we figured out how to leave scribbles in a cave using stains squeezed from leaves, we have been leaving marks of what we mean to say. Of animals. Of gods. Of lovers. Of yearning and despair. As our media of expression became networked, we began expressing more vividly.

You may not have noticed it, but our logo features a printing press. The hand-powered kind. It is an ode to Gutenberg and the ironies of information dissipation. When Gutenberg printed the Bible in the late 1400s, little would he have known about how his invention would fuel the distribution of information.

For instance, by the 1600s, almanacks (or dense works of scientific literature) would be a key form of literature that was consumed in Europe. The ability to print and distribute ideas is partly what helped the scientific revolution. You can talk about how the Earth is not the centre of the universe without being killed for saying it.

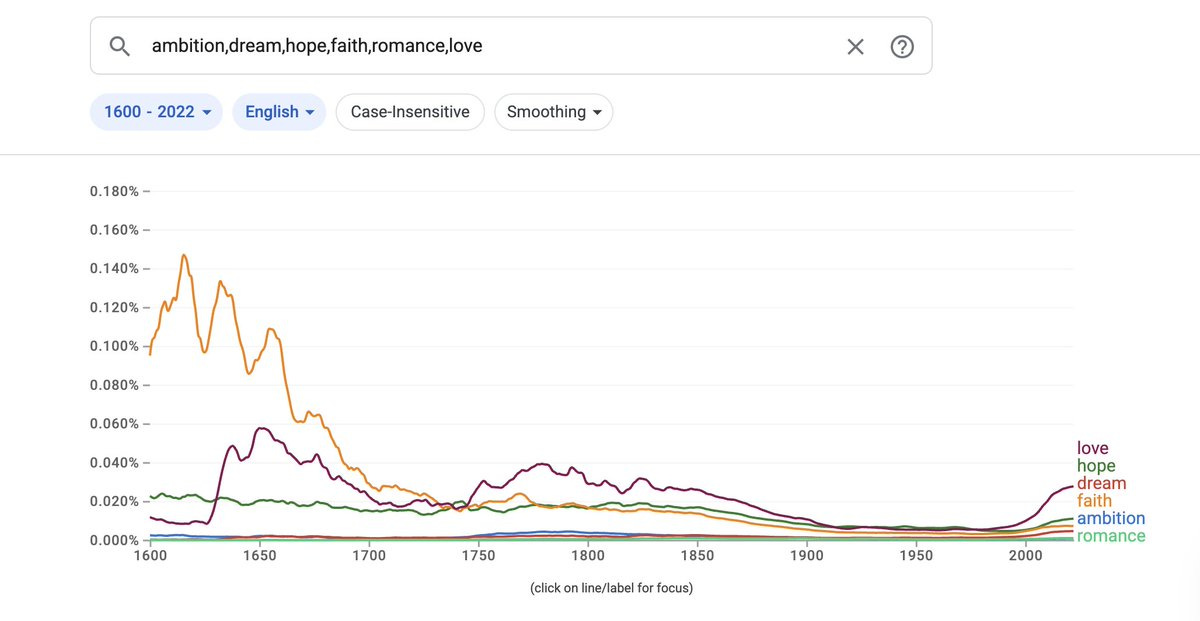

As you can see from the ngram above, the number of references to faith in literature has reduced. What took over was the term “love”. Now, I do not mean all of Europe gave up on religion and decided it is time to find better partners in life, but the nature of the medium did change. An instrument (the printing press) that initially spread the faith may have contributed to its downfall.

The printing press is symbolic of how the use of information or technology can be predicted once it is set in motion and unleashed.

It took the medium of written text from a social good to a private one. Around the 1700s, it became increasingly common for people to stop reading aloud. Instead, they read in the silence of their bedrooms. It makes logical sense. Before print media became common, neither books nor literacy were common.

So, reading was a social activity where people read together, with one person holding a book and reading it aloud. As books became affordable, and the nobility found itself with more time to spare, silent reading became frequent. The loss of control over what ideas spread through these books led to a moral panic at the time.

Families were worried about their teenagers spending their idle time reading about love instead of participating in the Industrial Revolution.. What is apparent is that the medium went from a public affair to a private one. From temple sculptures and monasteries to printed leaflets held in private. And that changed the nature of the ideas that spread. It went from deeply religious to the scientific, romantic and political. All of which were segments that had no means to spread in private discourse until the arrival of the print medium.

Churches, kings and nobility had no reason to publish treatises on how power works.

This may have contributed to the political uprisings of the late 1700s, when both France and the United States of America decided it was time for a change in their governance. Let us not get lost in the weeds; we still have another century of media to run through. Radio, television, and the excellent Internet itself!

The nature of monetising would change how the media operates in the coming century. Goods like Radio and Television broadcasts relied on as many people as possible tuning in at any one given time. This means you could not focus on isolated core niches. Prime-time television is almost always news bulletins and not a steamy romance because that is what families watched together.

The nature of views shared would almost always be in sync with what was acceptable at the time. (This scene from The Crown beautifully captures how television as a medium was used to bring the queen closer to her people.)

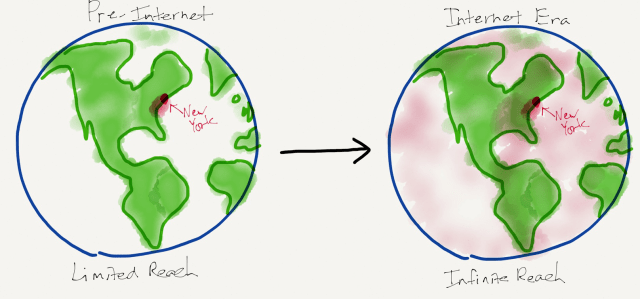

Ben Thompson captures this transition quite beautifully in this essay on never-ending niches. In the 1960s, I may not have had an avenue to write about emerging technology (say, debit cards) and find a large enough audience on the web. As a creator, I focused on what is relevant for my geo-specific audience. The Internet changed that equation. It allows me to find people across the globe who are interested in digital economies. Our audience consists of people from 162 countries.

That is entirely because of the power of the web.

This scale also influences how culture dissipates.

There’s a commonality between JK Rowling’s Harry Potter, Jay Z’s Blueprint Album, and Dr Dre’s headphones. All of them are beautiful bits of art, but they compound in popularity and become centres of capital. In the process, they form a flywheel where money helps distribute the art, and the art helps compound the money.

But underlying these shifts is a common element.

It is technology.

Platforms like YouTube, Kindle, and Apple Music helped disseminate their work to a global audience. Culture did not center around the cities where they were based. Instead, it was an international audience base that consumed and believed in their art. It drastically scaled their audience base, thereby improving their unit economics. Platforms, in turn, benefited from the users who came to these products.

A common culture is the easiest hook when you are trying to onboard large troves of users to a product. I wrote about how SuperGaming uses IP from well established brands to scale games in the past. As of writing, they are at a little over 200 million downloads.

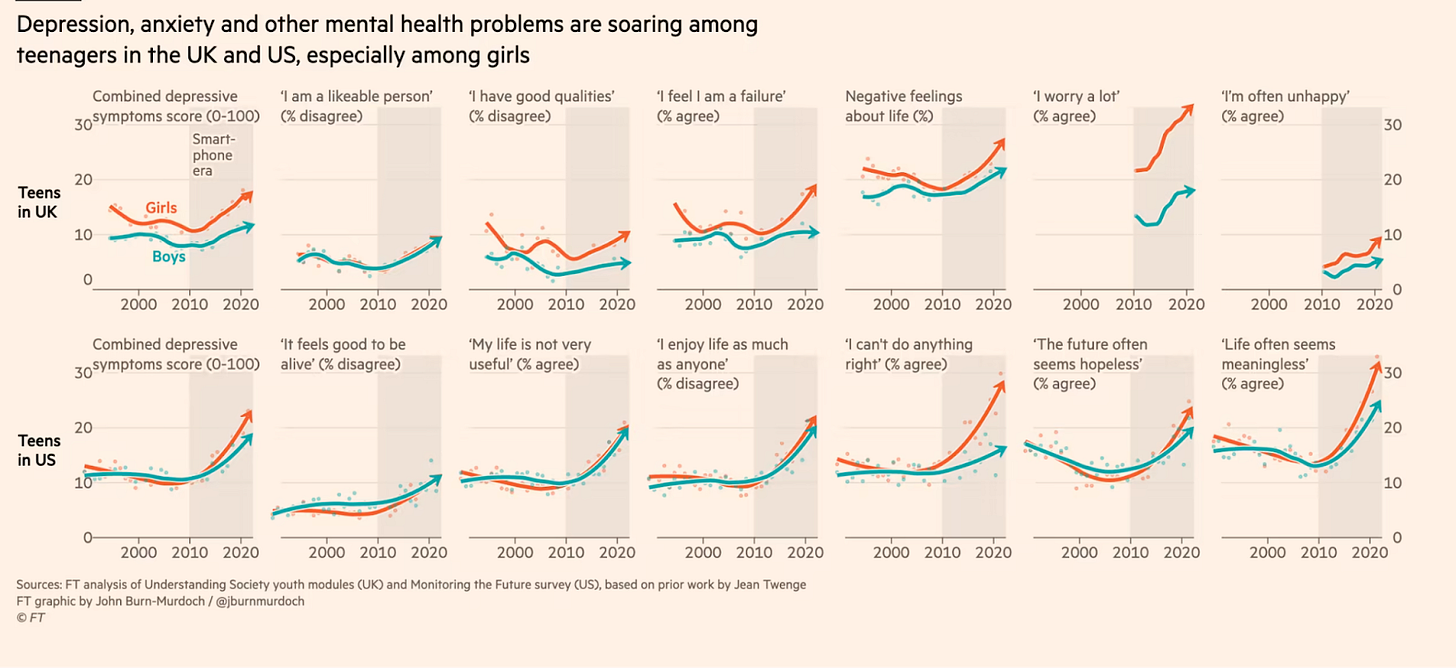

In the age of AI and algorithmic feeds, culture tends to concentrate. Instead of being on the hunt for new media, a teenager today could find himself in a vortex of content that further enforces his worldview aggressively. The risk is exacerbated with LLMs as instead of seeing human generated bits of media - one simply talks to a chatbot that enforces existing ideas. And that could lead to fatal outcomes, including suicide. On the flipside, the same tool is also being increasingly used for therapy.

This is where you see the dual nature of how a technology like the Internet works. On one hand, it is the single best place for a boy from a small town in India to discover the best artists and aspire to be like them when he grows up. On the other hand, it is also the best place to find terrible ideas and get caught up in a vortex of content that reinforces them. This explains why society seems increasingly torn. Instead of conversation, we have algorithmic reinforcement.

Instead of lore, we have content. We traded depth for virality within niches.

Who cares about the truth if it brings clicks?

When everybody has only fifteen seconds of fame, we trade the nuance of what makes our stories for catchy tunes and flashy moments. The stories, emotions and virtues that pass through the ages become compressed for a quick jolt of dopamine between meetings. The human experience becomes one long swipe, followed by another. A persistent pull of the lever at the modern age casino for content we relate to. Gone are the stories grandmas once told their grandchildren. Google Gemini now produces them, as nobody has the time or patience for it.

We traded physical love letters for snarky pick-up lines on dating apps—the limited tangible created by effort, for the infinite intangible marked by machine-produced drivel.

How does this translate to crypto?

To understand, we need to see how the industry evolved.

Transformation

From Michelangelo to Jay Z, from the Medicis to SoftBank, it becomes all but apparent that capital helps scale culture. More people become accepting of a culture when there is monetary stability attached to it. And technologies, like the printing press, radio or the web, help with distributing it. Capital is needed both to create art, and the means to distribute it.

But what happens when the medium of expression is money itself?

That is the multi-trillion-dollar question crypto seems to struggle finding an answer to.

Crypto started with the intentions of replacing banks with cypherpunk values. It makes sense when you consider that many individuals who were on the mailing list Satoshi sent Bitcoin’s whitepaper to had run into trouble for their work on encryption at some point. In the early 1990s, exporting encryption software was compared to exporting nuclear weapons. So you can understand why there would be deep-rooted suspicion and hatred for the government during the early days.

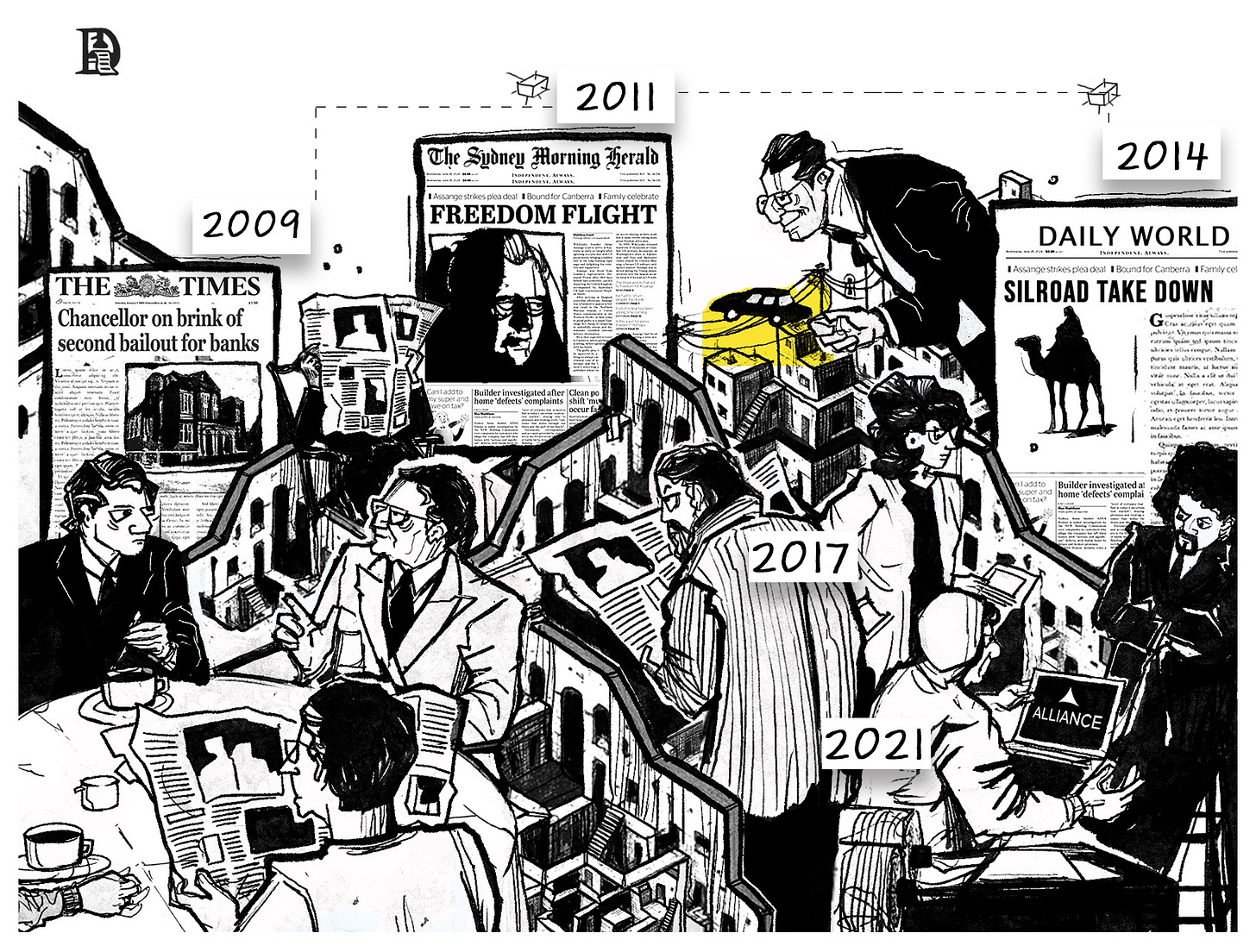

The early adopters for Bitcoin were not fintech enthusiasts. They were drug markets like Silk Road and debanked firms like Wikileaks. When WikiLeaks embraced Bitcoin due to being deplatformed by PayPal, Satoshi suggested they had kicked the hornet’s nest. This was in 2011. When Bitcoin was still at the periphery. As a sector, the industry began capturing attention with the ICO Ethereum did in 2014. Cosmos ICO in March of 2017 set the stage for what would eventually be a boom for everyone trying to put things on a blockchain.

Uber? On the blockchain. Tinder? Yep, on a blockchain. Your local government? It needs to be on the chain!

We are going to put it all on a chain and tokenise the life out of it, because the world needs more decentralisation. Just kidding - with a tinge of sadness.

Two factors played a role here.

Smart contracts on Ethereum made it possible to issue, transfer and trade assets easily

Capital formation happening on-chain was a novel idea. Founders could bypass the evil VCs and raise funds from the “community”. Or, people who intended to sell the tokens for a profit.

ICOs allowed VCs to have liquidity on their equity investments while allowing retail participants to come onboard. The great promise at the time was that venture capital as a business model would be upended. The culture of the time revolved around how shared ownership of an asset (usually a token) and distributed governance (usually through a DAO) could lead to far better outcomes.

Like many chapters in financial markets, the times were marked by vivid optimism. Until asset prices went down.

As the market evolved, crypto bifurcated into two user tropes. One group consisted of quants and the other was made up of farmers.

The quants were mostly sophisticated traders who would use pools of money, access to information, and a general understanding of finance to make wealth.

The farmers are the conventional users in crypto who contributed raw labour to protocols. I’d think I was a farmer myself, as most of my crypto comes from labour contributions (in the form of IP) to protocols. The long-tail of farmers were users who would go the extra mile for an airdrop.

You did not even have to release a token. You could just call them points and sell a dream.

We went from wanting to topple governments to hoping for airdrop subsidies as cold, brutal bear markets arrived.

All of a sudden, it was not about decentralisation. It was about what token could be perceived to be the most valuable. This rhymes with how media itself evolved. From a medium of private consumption to one of social reputation, as I explained earlier. Surely, the ICO boom cooled down by 2019, and nobody was able to raise any more by simply issuing a token.

But the mechanisms of signal evolved. Markets began pricing a token on the basis of which VC had invested and which exchanges are likely to list the token.

Like any industry in its infancy, we meandered to find our voice. Am I supposed to call everyone a ser? Should I really be on this DAO call? Who cares. We had founders using DAO tokens to buy mansions. We had Snoop Dogg buying real estate in the metaverse. Maybe I should visit his land and check if Dr Dre is still Dr D.R.E

We confused a large group of members on a Discord chat for a community. We argued that tokens are a product. That its price is a sign of product-market fit. We overlooked the fact that protocols with billions in valuation often generated less than $100 a day in revenue. We confused founders discussing a problem with their ability to execute on it. And above all, we confused technical jargon to be a sign of novelty and competence.

When Bitcoin rallied in the post-ETF boom, and most alts did not, we woke up to the sad reality that the emperor has no clothes.

The meme-coin resurgence of 2024 was symbolic of a market waking up to the realisation that volatility has been the product all along. As long as numbers went up, and a sense of fairness in how these assets were issued existed, the people would come and trade. Between WIF, Fartcoin, and a mix of assets that made no sense, we realised that sometimes speculative assets are also a medium of expression. And the common sentiment in all these assets was the same message.

A desire for profit.

Crypto culture shifted from being about ideology or technology to being about the behaviour it unlocked. The focus switched towards trading. And that made sense. If blockchains are money rails, then the core purpose should be the fast and efficient movement of money. All else is a distraction. Except that staring at us blissfully are alternatives that emerged amidst this. Ones that show signs of a parallel culture forming in crypto.

Most products that scale tap into behaviour that may seem weird outside. Layer3 can be easily mistaken for a platform used by airdrop farmers. And yet, if you study their business, it becomes apparent that they have built a full-stack solution for onboarding millions of users to Web3. They offer tools for on-chain reputation, wallets, swapping and support the highest number of chains. What could be dismissed as a questing platform, is now the definitive product for early stage products’ growth. (I say this, as we use them quite often for our own portfolio of startups).

In the same vein, NFTs were considered dead technology. And yet, Pudgy Penguins proved the exact opposite. They partnered with Walmart to generate $10 million+ in revenue. The brand itself has garnered close to 120 billion views on its assets, with some ±300 million views coming into its IP each day. Pudgy took a crypto-native primitive and took an entirely different approach to making it relevant. Partnering with retail outlets and leveraging web2 social networks to gain attention.

Both these products question what even is crypto-culture? Is it the mindless speculation on memes? Is it getting liquidated on perpetual exchanges every day? Or perhaps - it is betting the farm on a token that was released last night because Artificial intelligence is going to disrupt jobs, and we have less than two years to exit the permanent middle class?

The markets have given us the answers here. Crypto is simultaneously a medium of expression and a culture of transaction. Consumers have embraced its ability to be a stable transfer of value. That is why stablecoins have become a dominant mechanism to move money around the globe. But at the same time, it has rejected some other ideas. Play-to-earn, for instance, died a disastrous death. As much as I want it to be the case, content coins have gone nowhere either just yet.

I check what my friends have shared on Instagram each day. I don’t know what my own content is worth on Zora. (And that is sad).

Much like free-speech cannot exist without a few offensive things said, resource coordination at a global scale may not exist without bad actors exploiting a market. In both cases, there are consequences for actions. Do it badly for too long and there will be nobody left to listen to what one has to say or buy the assets one issues. Crypto Twitter may ironically be dealing with the consequences of both at the same time.

It is important to acknowledge that crypto’s evolutionary arc rhymes with how most mediums evolve. We don’t know of the thousands of books that became irrelevant. The web is littered with millions of blogs nobody knows or cares about. Social media works because people express content that dies within a day. The same will happen with crypto assets too. There are over forty million tokens. Many of them will go to their fair value - zero. Content coins may be remembered fondly someday, like one often does with their NFTs from 2021 or ICO coins from 2017.

Irrelevance is the norm for most things.Unless there is culture involved.

A culture is often defined by how it communicates. Words dictate how we feel and understand the world around us. Until 2021, one could afford to speak in jargon. And yet, as we bang on the boundaries that go beyond this core niche, we would have to speak less in jargon and more in what clicks with people - an art form we have been trying to perfect here at Decentralised.co

For instance, your dating app cannot simply be talking about how it is powered by zk-proof. The people just want dates. Stablecoins don’t compete on how many networks they are supported on. People simply choose the lowest-cost, fastest mechanism of moving money globally. The consumer cares about what is offered today, not hypothetical layers of what could be possible in the future.

The closer our industry gets to consumer products, the higher our requirement to be able to speak in a language that makes sense to the marginal person on the web. And because languages are often developed as a function of where one belongs and how often one interacts with one another, we will have to change how these consumers are onboarded and retained.

The Medici of this new age will be merchants of attention.

Ironically, the Michelangelos of this new age, will be artists defining capital flows.

Let me explain.

Absolution

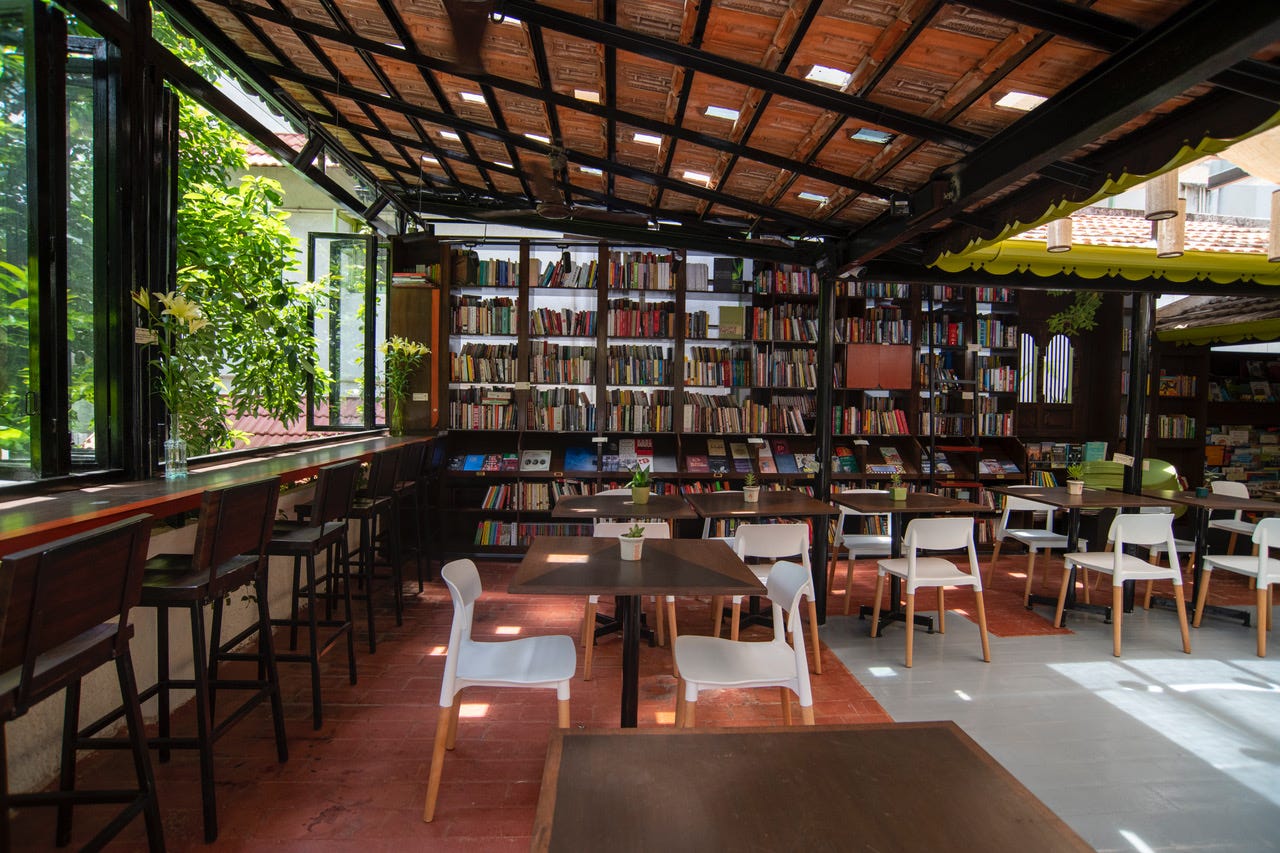

One way to think of crypto is through the lens of a casino and your neighbourhood cafe. A casino is indeed an environment with high monetary velocity. People do move money on its products quite frequently - but the house often wins. You don’t see people camping at a casino for long. Or most people don’t. In contrast, your neighbourhood cafe attracts people day after day.

Usually, the same subset of users that come around with coffee as an excuse for gathering around. They share stories and the bits that trouble them. The calm and the joy the space offers are what brings them there. In more religious societies, a temple or church plays similar roles. The coffee, or faith, becomes the substrate that brings people together. But they stay there for reasons beyond the underlying product.

A culture is the collective of stories that people share with each other. Too often, the stories we share today are price charts. And when those price charts turn red, people have little incentive to return. How do we keep people coming back? What are the levers we have to make this technology cross the chasm?

To understand that, perhaps we should look at the web itself.

There are two forces moulding the web.

One is that of endless amounts of content being created in the age of AI and LLMs. When everyone’s a creator - nobody is truly one. People will need mechanisms to own, monetise and distribute their content.

The other is that of verifiability. Endless AI slop works in the attention economy (of X or Instagram) as it keeps people engaged longer. More eyeballs, more clicks, more dollars.

Everything crypto can do for the internet can boil down to functions of verifiability and ownership. These ideas are not new. We have discussed them in this publication since 2023. But changing regulations and attitudes of capital allocators are the primary reasons why now is the time to pursue these opportunities.

The web has always been a tool to express freely. Crypto enables people to own the avenues and networks through which these expressions are created. It also allows assets to be issued, traded and held freely. Meme coin mania is what happens when everyone gets to express themselves monetarily.

When the internet came around, most people marvelled at how it would enable jobs to evolve. However, much of what drew retail users to the internet was not the promise of employment. It was the probability of entertainment and finding friends. Meme assets are similar to entertainment for the age of crypto, but they struggles to have lindy effects due to the losses associated with them. Maybe, not everything should be a transaction.

Only about 1% of the internet posts content. If I draw a parallel to crypto - there may be a world where users do not transact for 99% of the time they are in an app. Figuring out ways to bring users together, without transaction being the core value proposition, is where all the magic lies for the next generation of consumer applications.

I know - it sounds ironic. On one end, I argue blockchains are money rails and that everything is a market. But on the other hand, I also acknowledge that having your users transact all the time will lead to issues of churn. Attention, as they often say, is all you need.

What could that look like?

Here are some early observations from social networks and entertainment.

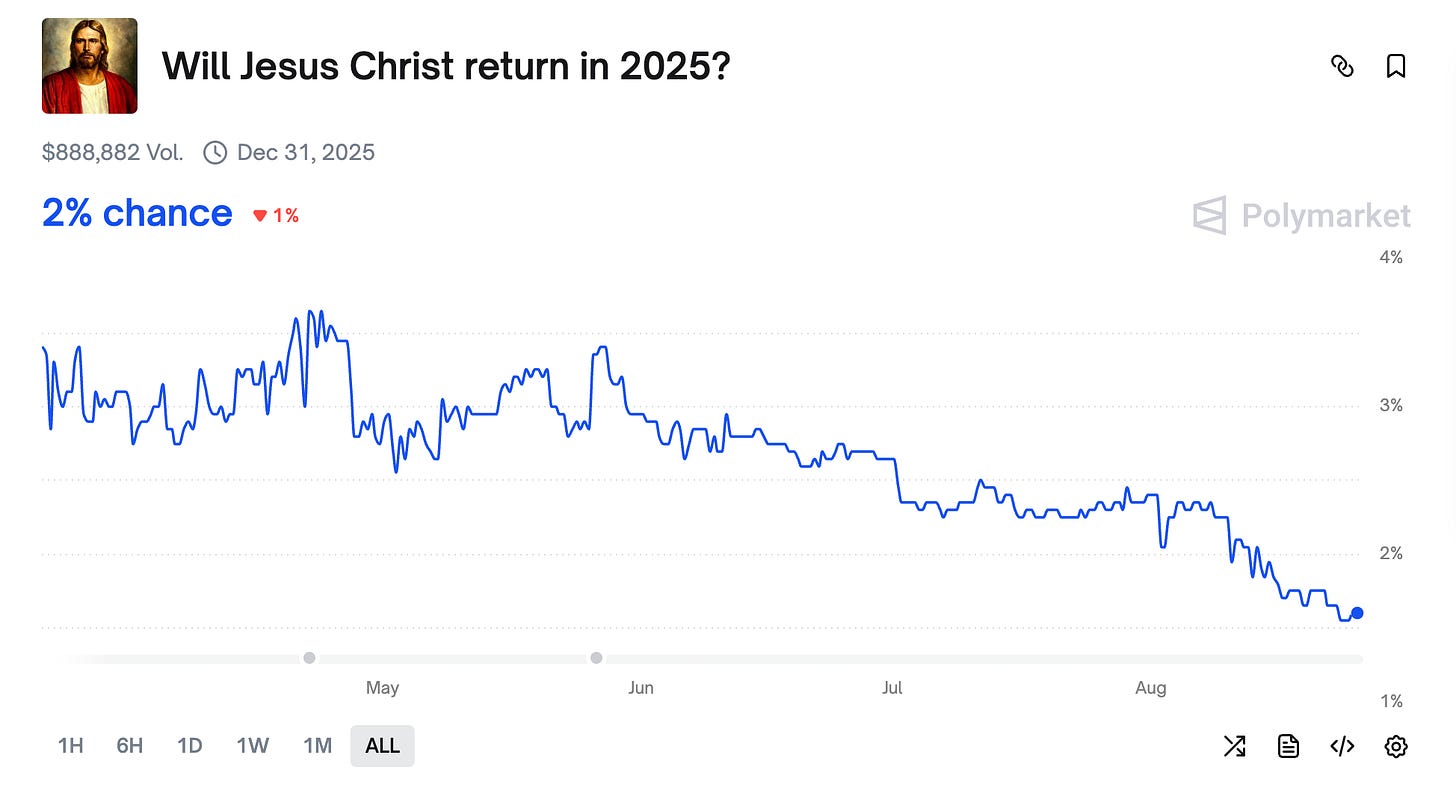

1. A social network built around prediction markets.

Currently, prediction markets already reach out to large creators, suggesting a prediction market be embedded in the piece such that a portion of the transaction fee passes on to the creator. Twitter is about to integrate Polymarket into its feeds. Such modes of attention and transaction economy blending together will be powered by crypto-rails.

2. A Music Streaming platform with better unit economics.

Spotify pays about $0.03 to $0.005 per stream today. That is partly because revenue is linked to keeping subscription costs lower. Allowing creators to issue digital memorabilia and garnering fees from it may be one way to bring that number higher. For instance, I’d love to own a signed vinyl of Fort Minor’s Rising Tied album.

Maybe, there’s a world where the vinyl is issued on-chain, but redeemed off-chain at a later point in time. Such business models are already happening in isolation. You can buy gaming card packs from Courtyard - but the social or streaming elements of it are in isolation.

This is not to imply financial primitives don’t matter. We have been talking about Hyperliquid, Jupiter, and similar revenu- generating apps for a reason. They are the modern-day equivalents of the Medic banki. Capital concentration enables experimentation with new tools that garner attention.

But the way to sustain it is through building products that keep people coming back for reasons that don’t involve placing a bet. Transactions need to evolve beyond simply speculation.

All of this makes me think - what even is a culture?

It is the collective of stories we hold dear to us. The exchange of Pakistani songs with my cab-driver on a ride back home from the office. Me saving Kheer recipes on Instagram because someone I love told me her mum bribes her with it when she’s sick is also culture. I recommend Jab We Met, Veer Zaara or Laapatha ladies when someone asks for Bollywood movies because I think they represent the culture (fairly) well.

Perhaps, it is me thinking of praying at a church my family has been to for three generations because a loved one was diagnosed free of a disease.

There is no monetary value changing hands in any of these cases. But there is a substrate defined by shared stories and sentiment that holds us together. There is a sense of belonging that makes things priceless. They are all momentary expressions that give value to life. Core to my identity. Momentarily expressed, they add density to the rest of life. And somehow, the same sentiment reflects in products too.

Look at an Apple product long enough, and you’d trace back elements of Steve Jobs’ time at Disney in it. Pick an iPhone and you would feel his desire to make something wonderful. And these bits are what keep you buying iOS products year after year - even when the changes are abysmal.

Products in Web3 rarely get to replicate that substrate in scale. In Web2, it was built intentionally. Facebook, for instance, did not launch with a points programme. It focused on Ivy League graduates for its substrate. Quora, at one point, the best place to get insights from developers in Silicon Valley. Substack remains the best place to find literature on the web. Web3 products also have their substrates.

Look at PumpFun’s feed long enough, or discussions on Polymarket, and you’d see a nascent culture forming, but like any sector in infancy, it struggles to stick.

Remember how I said the web changed love letters to short texts that require no effort? The web also upended how people find love. As of 2023, 40% of all couples met online. And ironically, to me it shows how technology works. On one end, it changes the mediums of how we express ourselves. On the other hand, it increases the surface area of randomness for beautiful things to happen.

By sticking to our perception that crypto is only about speculatory apps, we give up on the surface area of randomness that could exist.

Maybe it is time to see crypto as a medium of expression. Perhaps it is time to think about an alternative culture for the industry we spend so much of our lives in.

Cooking up a Renaissance,

Joel John

Enjoying these posts a lot.

Keep them coming sir.

Hyperliquid

“Crypto culture shifted from being about ideology or technology to being about the behaviour it unlocked.”. 👏