Money Moves 💸

On Monetary Velocity & Fee Models

Hello!

Sid and I will be at Token2049 in Dubai next week. If you are coming to town, drop us a note by responding to this email. We are in the middle of scheduling meetings and would love to meet long time readers of the newsletter.

Today’s article stresses on a simple question. What happens to business models when the cost of moving it diminishes rapidly? New networks like Monad and MegaETH will collapse the time taken and cost incurred on each transaction in the quarters to come. I draw historical parallels to explain why everything we do on the internet is a transaction and what that means for crypto.

On to the issue..

Joel

Hey there,

Some might call it an addiction, but I often catch myself wondering, “How much coffee is too much coffee?” At some point, you probably reach a level of caffeine in your bloodstream where injecting more coffee has less ROI compared to simply hydrating yourself. The mind thinks it needs more of the anxiety-inducing Renaissance juice. But the body is better off with the simplest and most basic liquid known to man.

Markets are a lot similar. We tend to think that more of a good thing can lead to better outcomes. But resetting to a new normal could be the need of the hour. When tariffs stabilise at predictable levels, industries adapt and recalibrate to a new normal. When venture funding slows, weaker firms are filtered out, creating more stability for the ones that remain, until risk-taking becomes attractive again. Where am I going with this? I think much like my caffeine consumption, we have reached a local peak for capital velocity and fee extraction. The best use of the industry’s time is figuring out how to sustainably increase both.

The markets are accounting for this fatigue in strange forms. VCs would argue we don’t need more infrastructure. Marketers would argue that our focus should be on the consumer. Analysts would suggest that we require products with economic fundamentals. Traders want more volatility. As with many things in life, the truth lies buried in the incentives that drive these characters to think the way they do.

But if we were to be objective, we can look at blockchains not just through scale or throughput, but through the lens of the take rate per transaction. Blockchains, at their core, are networks that facilitate the movement of money. They are thriving transactional ecosystems that work at a global level and in real time. Bitcoin serves that function quite well and has earned its status as hard money. But what about the other applications?

Put differently, what would happen to digital economies when money moves at the speed of information on the internet? How will capital formation and allocation evolve when the movement of money becomes as easy as a click? In today’s issue, I tried to find answers to these questions.

Digital Malls & Smoke Grenades

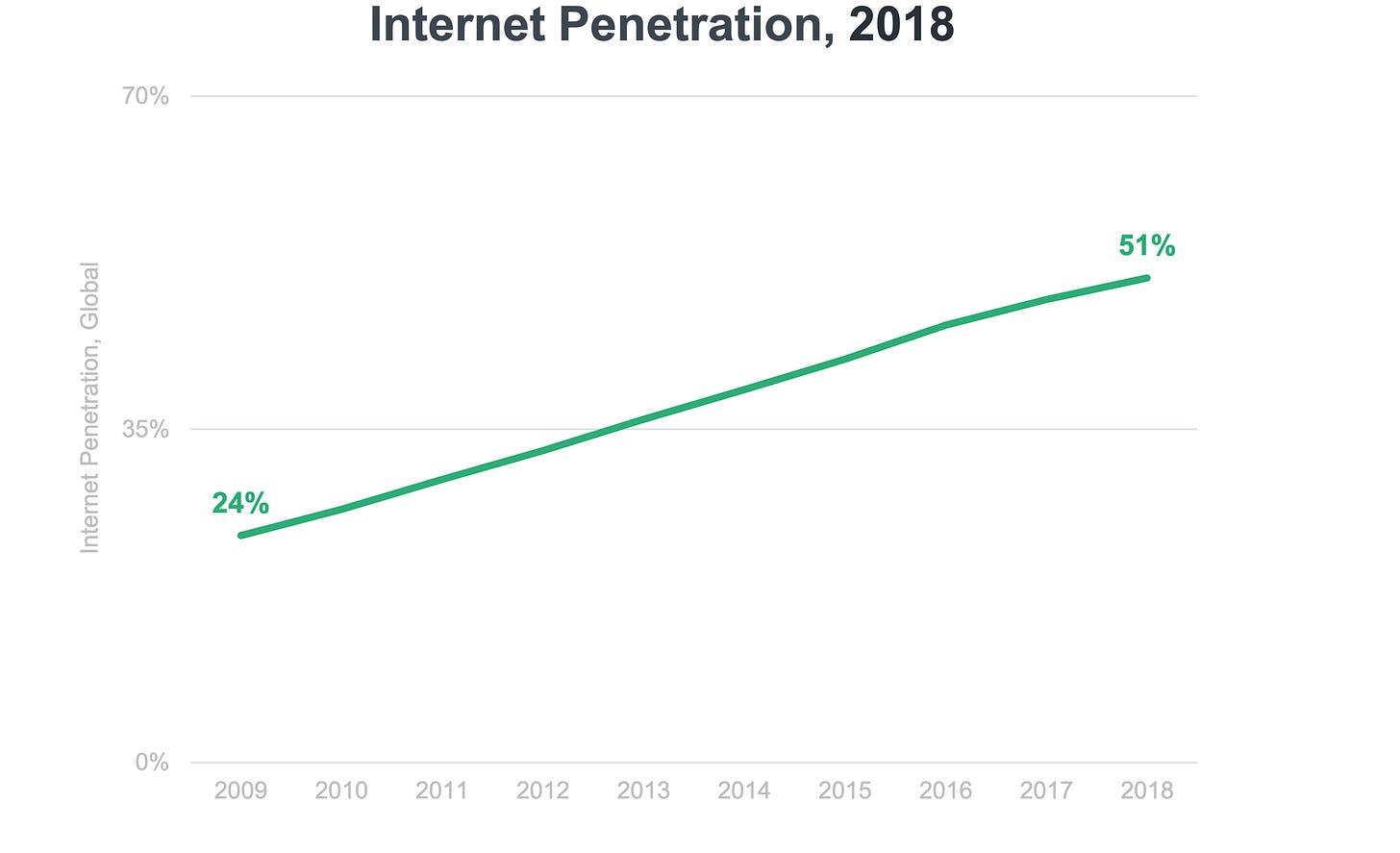

The internet is a transactional system, you just don’t realise you're transacting. In 2001, Google’s ad revenue was $70 million, with each user contributing roughly $1.07. By 2019, that number ballooned to $133 billion—$36 per user. In 2004, the year Google IPO’d, 99% of its revenue came from ads. The story of the web is, in many ways, a story of how ad networks managed to extract 40x more value per user over a 25-year span.

You might not think much of it, but every time you scroll, search, or post, you’re producing a commodity: human attention. At any given moment, you can only focus on one, maybe two or three things at once, assuming you are playing music, texting and trying to work at the same time. And attention economies are designed to monetise that limited resource in two key ways:

First, by optimising for information collection on the individual. On social media, this happens fairly easily as the user gives feedback to the platform (like X, Instagram or TikTok) on the basis of the type of content they spend time on.

Second, by optimising for engagement time. Netflix was not joking when they said that sleep is their competitor. As of 2024, the average individual spends 2 hours per day on the platform, of which 18 minutes are spent trying to decide what they want to watch.

In short, you are not the customer. You are the product.

In any given year, you are expected to spend the equivalent of four days scrolling through media apps to pick something to watch. I fear doing the math on how much time is spent on dating apps. The internet is interesting because we have figured out how to capture value by keeping users engaged longer and sharing more of their information. The reason why the average person does not know how this works is because they don’t need to.

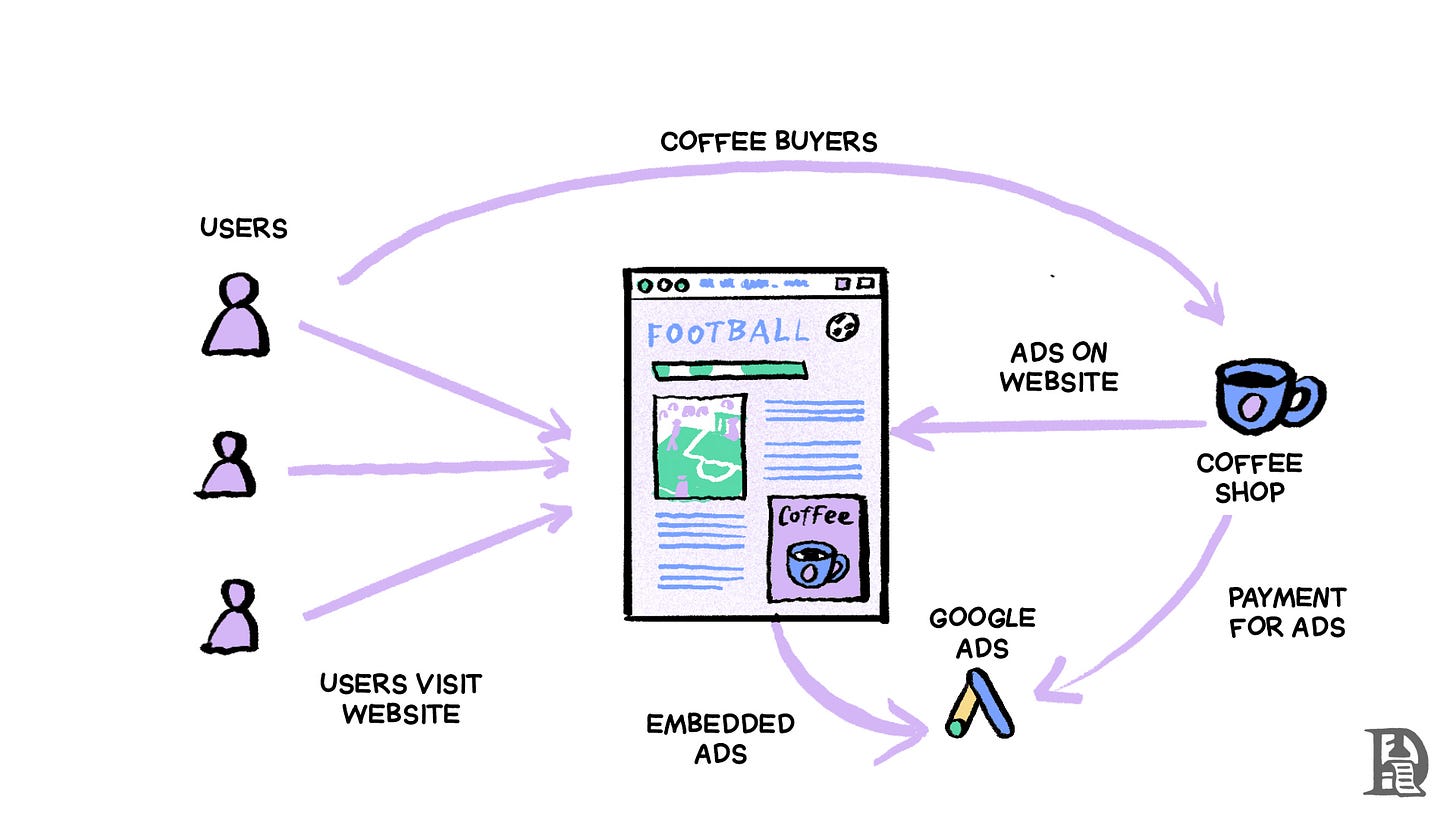

Think of internet platforms as massive digital malls. When you spend time on X or any of Meta’s apps, businesses pay the mall owners (in this case, Musk or Zuckerberg) for the chance that you might eventually make a purchase. Attention is the equivalent of footfall in these digital realms. Why does this matter? Because in the early 2000s, the more ‘primitive’ malls had a problem: users didn’t have debit cards, and businesses couldn’t accept direct digital payments. Trust and infrastructure were both missing. So, instead of charging users, platforms monetise indirectly through ads.

Advertising became the workaround for an internet not yet ready for seamless payments. And in turn, it created a new economy that ran digitally.

How did this system work? Every time you made a purchase online, the business would pay the platform (our large, digital mall) a cut of the transaction. On platforms like Google, this took the form of ad spend. In other words, it didn’t matter how the user paid for a product. What mattered was that platforms got paid directly and reliably by businesses through bank transfers and debit cards. Businesses had employees to figure out payments and logistics. Users? They were too busy dodging malware from LimeWire. So this model worked just fine. Platforms didn’t need to teach users how to pay, they just had to make sure the businesses paid them.

Fast forward to 2020, where the internet was obsessed with a magical thing called Bored Ape NFTs. OpenSea was the new mall. Ethereum was the payment network. Users flocked in throngs. But nobody quite figured out how to collect payments from these individuals without the complexities of on-ramps, on-chain fees, ETH price fluctuating, transaction signatures, private keys and setting up Metamask.

The products that grew the market in the years that followed, all had one thing in common: they lowered the barrier to entry.

Solana made it possible to skip manual transaction approvals multiple times.

Privy let users hold wallets without worrying about private keys.

Pump.fun let people spin up meme coins in minutes.

You get the gist. Markets reward simplicity. Nowhere is that clearer than in the rise of stablecoins.

Capital Velocity & Network Moats

In January 2019, the total supply of stablecoins was just $500 million—about the same as some meme coins have been valued at in recent months. Today, that number stands at $220 billion. A 500x increase in six years is the kind of growth few metrics ever see in a single career. But it’s not just supply that’s exploded. Profitability has scaled right alongside it. In just the last 24 hours, Tether and Circle generated a combined $24 million in fees. For comparison: Solana brought in $1.19 million, Ethereum $975k, and Bitcoin $560k.

This may seem like an apples-to-oranges comparison as one is a financial product and the others are payment networks. But there is a lesson in there when you consider that close to $7.5 billion has been generated between these two stablecoin issuer over the last year alone. The numbers are even more impressive when you consider that a volume of $33 trillion has been moved through stablecoins by a combined 240 million active, unique addresses through 5.4 billion transactions.

And yet, all the fees generated by stablecoins do not come from users. They come from yield generated from a mix of U.S. Treasury bills and money market funds. This excludes revenue from minting and burning.

When a user pays in stablecoins, there is no fee in dollar terms on the stablecoins held. You can send $10, $1k or $10k with the same $0.05 transaction cost on Solana. This is different from a payment made with Visa or Mastercard, where you can expect a 0.5-1.5% transaction fee. And yet, stablecoins continue to be some of the most profitable businesses in crypto. Why is that the case? They solve user complexity in three ways.

They make a highly desirable asset (the US dollar) available to individuals across the world

They have the highest velocity when taking into account the forms of US dollars. Be it Paypal, Wise or a bank transfer, stablecoins facilitate quicker cross-border transactions.

The network effects of products like Kast, a card that allows you to pay for real-life expenses using stablecoins, would mean more users grow comfortable with receiving and making payments in stablecoins.

I find that the most profitable parts of an industry that is obsessed with decentralisation make their revenue from centrally owning T-Bills and issuing dollars on-chain. And yet, it is the nature of technology. The average person on the web does not care about the extent of decentralisation as much as they care about what a product can do. They don’t care about L2 purity tests as much as they care about transaction costs. And when seen through those lenses, stablecoins are simply a better form of dollars.

The innovation was not simply in issuing dollars on-chain. But rather in abstracting the fee complexity away from the user, like we saw with ad platforms in previous generations. The real genius in stablecoins is in finding a reason to park a tremendous amount of dollars into T-Bills and surviving on the yield that comes from them.

It may seem like Stablecoins are winning. But if you look at it from the perspective of capital velocity, traditional payment networks are not far off. Compared to $33 trillion moved on-chain via stablecoins, $13.2 trillion was moved on Visa alone last year. Mastercard did a further $9.75 trillion dollars. So between them, they do close to 22 trillion dollars annually. Compared to the 5.4 billion transactions done on stablecoins last year, Visa alone processed 233 billion. One would think the amount of money moved on-chain would be far higher given lower transaction costs, but traditional payment networks have more in volume and transaction count.

Purely in terms of capital velocity, traditional payment networks do a better job. But that is not because the technology is inherently better. It is because of entrenched network effects that have taken decades to play out. You can turn up at a Matcha store in Japan, a baguette spot in France or my favourite spot to ride a bike in Dubai, and hope to pay through the same instrument—a debit or a credit card.

Try doing that with stablecoins stored on Polygon or Arbitrum and let me know how that goes.

(Note: I did in fact try it and ended up spending 20 minutes waiting for a bridge transaction to go through. At least the ramen I had just had was delicious and worth the wait.)

The reason why I make that argument is because our industry tends to routinely argue that stablecoins are inherently better than fiat transactions for all use-cases, when in reality, the fee Visa or Mastercard charges is comparable to what any offramp charges for converting on-chain stables to real-life dollars. This is like arguing digital media is better than printed newspapers in all use cases. It isn’t. If you live in a remote hill with no access to a computer and the internet, a printed newspaper is the best way to consume media.

Similarly, if you are not active on-chain, a debit card is the best way to pay. But if you are online or on-chain, the experience can be distinctly better. Knowing how to discern between what is on-chain and off-chain, and the distinct forms in which value can be captured, could be key for founders designing digital economies in the years to come.

The Velocity-Fee Spectrum

How then should a founder be thinking of fee models and expanding the pie? Do we obsess about bringing people on-chain, or do we find a way to make these on-chain primitives useful? There are two ways to think, and both have sound, meaningful arguments to back them.

One argument is that revenue in crypto can be seasonal but have extremely high velocity. In conventional markets, one would think an increase in fees would reduce capital velocity. And yet, some of the most speculatory parts of crypto have had very high fees associated with them. During the NFT boom, OpenSea had a royalty cut of 5%. Friend-Tech charged close to 50% of revenue. In places where profit motives are the primary driver, individuals pay higher transaction fees and simply consider the cost of transaction as a cost of doing business.

No place makes this trend as apparent as Telegram trading bots. Over the past few quarters, products like Photon, GMGN and Maestrobot collectively made hundreds of millions of dollars due to three core reasons.

The seasonality of meme coins meant users had a new market (like NFTs in 2020) to speculate and profit from

The UX improvements caused by bringing the wallet to Telegram and making chat-based trade interfaces easy to use made it possible for users to trade from their mobile devices

The lower cost of transactions and faster speed on Solana meant users could trade back and forth multiple times in short spurts to compound profits.

The innovation was not just the asset (memes) but rather the behaviour that came as a result of cheaper, faster transactions on Solana and the distribution Telegram offered. Seasonal apps tend to struggle with stickiness, but the velocity of capital within them is so high that it does not matter if the industry collapses over a period of eight to nine months. Users pay extremely high premiums, and those selling shovels during a gold rush tend to do fine. The chart below shows how that played out for Photon.

One point to note here is that capturing high fees on high velocity works only when there is a lack of competition. Given long enough time, markets create sufficient competition to bring fees lower. This is why fees on perpetual exchanges have trended lower. Whereas with meme-market oriented products, the dominant players maintain fees as the market for meme-trading declined before enough competition arrived. Blur’s disruption of OpenSea’s model is an instance of fees declining when competition emerges.

The other argument is that sticky sources of capital, such as LPs on Uniswap or ETH-yield hunting depositors on Aave and Lido are the ideal market to pursue. In such products, the velocity of capital tends to be far lower. Users deposit capital once every few months and forget about it. Therefore, the fees charged by them tend to be on the higher side. Aave takes 10% of the interest repaid by the user. Lido takes 10% of staking rewards, but passes on half of it to node operators. Jito, too, charges 10%.

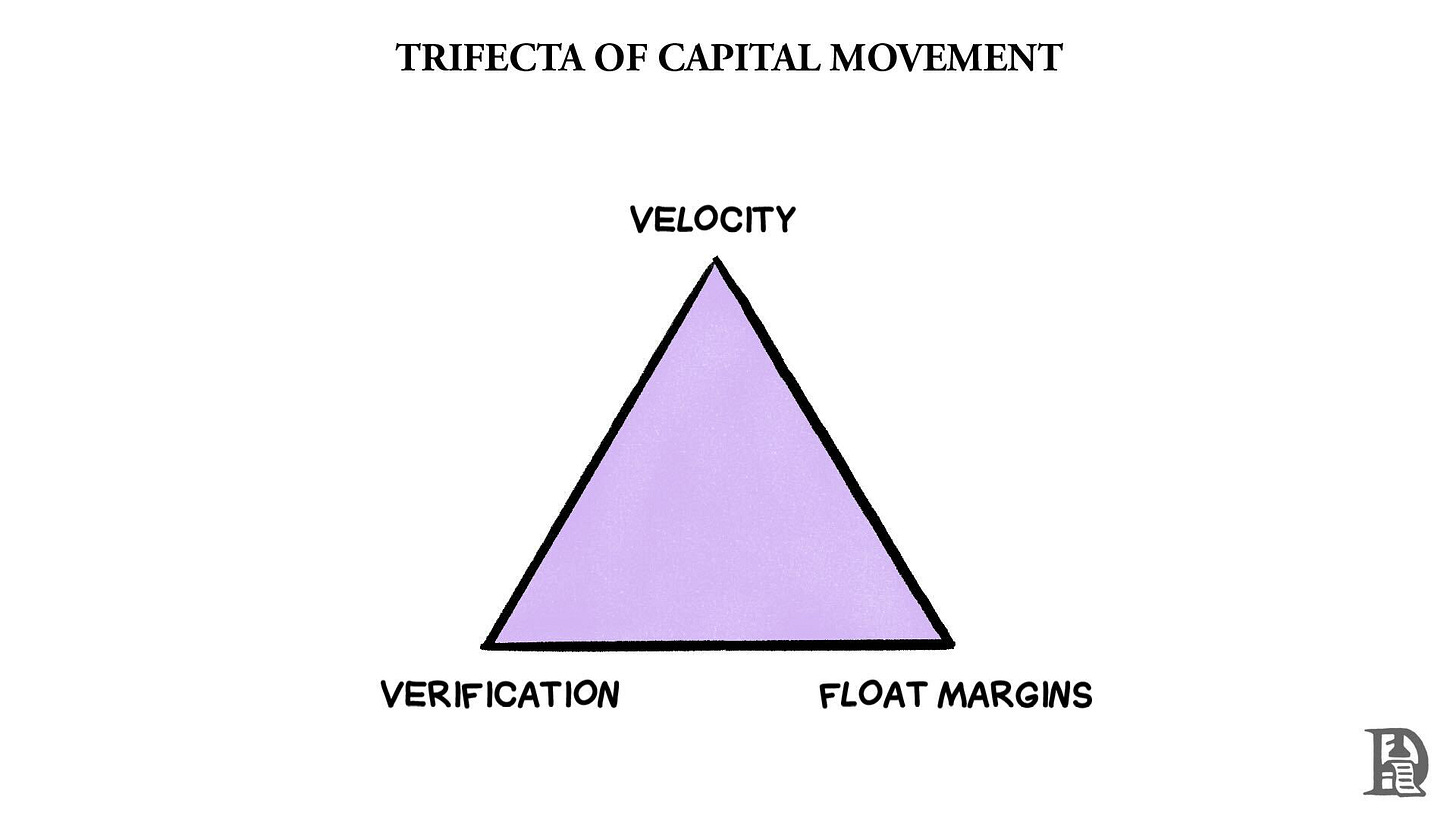

On the internet, there is a conservative law of velocity and fees chargeable: the more times capital changes hands, the lower the implied transaction fees.

If the capital sits idle, users can be charged at the rate of 10% of revenue. Seasonal markets - or high transaction velocity products (like HyperLiquid or Binance) see hundreds of millions in revenue due to the fact that users do repeat transactions hundreds of times over the course of a day.

Assuming no profits, a user only needs 69 trades with transactions costing 1% each to end up with 50% (0.99^69 = 0.5) of their initial capital. Assuming a loss of 2%, the user needs to do 23 transactions. This is partly why we see trading fees on platforms trending lower. Platforms like Lighter have trended towards zero fees. So does Robinhood. If these trends are to stay, we will inevitably reach a point where businesses will have to find alternative ways of generating revenue whilst keeping the users unaware of transaction costs. Something dollar-backed stablecoins do today

High velocity products (like digital payments) monetise on compounding fee loads. Low velocity products tend to monetise rails. In other words, the fewer opportunities a protocol has to touch the same dollar on any given day, the higher it needs to be earning from it for it to be sustainable.

Seasonal mispricing driven by speculation can make users pay high fees, on high velocity products. But what about non-seasonal products? Things like on-chain stocks and commodities? I had a chance to sit down with one of our portfolio companies’ founders to dig into that question. Usman from Orogold has been working towards building gold on-chain. The section below is inspired by a conversation I had with him over questionable amounts of coffee.

On-Chain Commodities

One tends to think that tokenisation unlocks tremendous amounts of liquidity for instruments. This is the reason why a lot of VCs, understandably, with illiquid equity books, think venture equity should be tokenised. But if meme markets have clarified anything, it is that liquidity tends to fragment over millions of assets within crypto. And when it does, there is little scope for fair price discovery. As a founder, would you want to compete with Fartcoin on liquidity? I doubt it. At least not at the seed stages.

Why then are exchanges like Coinbase and Robinhood rushing to bring listed equities on-chain? The rationale is fairly straightforward. There are two forces at play. One is that markets are global and function around the clock. Assets like Bitcoin have already become a macro-hedge during events where stock markets are set to slide and liquid hedge funds want exposure to an asset that moves in tandem. Last year, Bitcoin’s price moved prior to the Yen carry-trade blowup. It also front-ran the market’s pricing of Trump’s tariffs. There is a need for a market that is functional all the time, regardless of time and place. On-chain equities can play that role.

The other is the argument that there is $2 trillion of value within crypto today. That value needs a place to flow, and it cannot always be dollars. It definitely cannot be RWA lending either, because the risk profile is quite different. Commodities and equities coming on-chain, give this capital a safe place to rest. Naturally, not all commodities and equities are similar. The market for Uranium is a fraction of what it is for gold.

This is why we will (probably) see a top-down approach of major assets and commodities being tokenised first. What do you think has a higher probability of on-chain adoption? The S&P 500 or an index of early-stage venture equity? I lean towards the former.

When it comes to commodities, some are better positioned than others to find PMF. Gold, given its lindy effect and the fact that it is hoarded by societies around the world, is likely to see faster adoption than esoteric commodities. It also tends to be a good hedge against the dollar’s decline. But why would someone with access to ETFs or physical jewellery buy it on-chain?

Capital velocity is ultimately crypto’s killer use case.

Tokenised gold can move between markets at a much faster rate than gold bars. They are composable, such that lending against them is exponentially easier. It is also possible to loop gold and buy it on leverage on-chain, much like traders do with DeFi, if there is a lending market for it.

Commodities like gold will also have a stable bid, albeit inefficient in the early days, because there is a conventional market that is large enough to price it. It is different from tokenised real estate or startup equity as the pricing for it is agreed upon and does not rest on nuances of geo-specific or sectoral taste. Usman explained it’s role in Web3 through the following image. His core argument, is that any on-chain representation of gold will have to do better than its Web2 counterpart to be relevant. You can read more about what he is building here.

Remember how I argued that velocity and fees have a correlation? It gets interesting in the context of gold. If a platform (like Orogold) is able to charge small bps of fees on individual gold transactions (to and from dollars), they are effectively making yield on gold a reality. This could happen as fees for burning and minting too. In the traditional world, this does not happen as trading fees from ETFs rest with issuers or the exchange. Sure, you could lend it to specific outlets for yield, or your bank could make it a possibility, but would a person in an emerging market have access to that? I doubt it.

Bringing commodities like gold on-chain would also mean individuals in high-risk markets, where the risk of theft and seizure is high, would have the option of holding exposure to instruments without losing access. It also means a person can move these instruments around the world at the click of a button. It may sound distant, but consider that at any point in time, one can travel to a country today and find someone to convert their stablecoins to local currency. If gold is on-chain, the same could happen. Or maybe the person could simply convert their on-chain representations of gold to stablecoins and proceed with their day.

Bringing commodities (like Gold) on-chain is not about asset exposure or trading alone. It is about unlocking increasing velocity to generate yield. When fintech apps (like Revolut or PayPal) offer those instruments, we will have a new category forming on-chain. Challenges remain, though.

Firstly, it remains to be seen if on-chain representations of gold can produce enough yield through trading or borrowing to satisfy user needs.

Secondly, there is yet to be a large player for digital commodities that has also seen adoption by liquid hedge funds and exchanges, the way stablecoins have over the past few years.

All of this assumes zero risk on the custody and delivery of these instruments. Which is often not the case.

But as with most things in life, I like to be cautiously optimistic about the sector. What about things like IP rights, wine or content? Well, I don’t know. Is there a market that wants to trade wine hundreds of times on any given day? I’d think not. Even Taylor Swift may not want rights to her music tokenised and traded on-chain. The reason is, you will be putting a price on what is best considered priceless. Surely, there’s an analyst who can do a discounted cash flow on Jay Z’s albums and suggest the tracks are worth a dollar figure. But it does not work in the interest of the artist to enable a market for it.

The chart below should serve as a mental model of how the transaction frequencies will vary for on-chain assets depending on context.

When it comes to sectors like DeSci or any on-chain representation of IP, what will matter is the ability of a system to verify and validate ownership. That is, a blockchain could be used to verify if a piece of art is licensed and split revenue with the original creative in real time. Imagine if Spotify paid artists at the end of the day based on streams. Or if a translation of our articles into Mandarin paid us each day based on the traffic it pulled. Or the DAO behind a drug’s research being paid each day in proportion to how much of it is sold.

Such goods will also be able to charge high amounts in fees due to the complexity of validating whether a business has the rights needed to engage in a transaction. It has not happened yet as it takes time for the law to evolve. But in a world where LLMs produce content, and research stagnates, it is highly likely that we use on-chain primitives to validate, reward and facilitate co-creation of intellectual property.

Put differently, crypto-as-payrails will serve one of three functions: moving money faster (velocity); rewarding and identifying users (verification); or generating yield on idle assets, as stablecoins and on-chain representations of gold do. In other words, they put idle float to use. Great businesses almost always crack two of these three elements to gain an edge in Web3 revenue.

When Context Drives Transaction

I started this article explaining the web as a giant digital mall where the means of transaction did not exist. Blockchains change that equation. We are in a market where a shared global ledger (or multiple thereof) exists to facilitate transactions. Most of the time, meme assets are issued in response to news events. Polymarket has become a preferred way to come to predictive analyses of what reality is. Think someone from India could be the next Pope? You can spin up a market for it and put a bet behind that market.

Historically, media and much of our social interactions did not have a capital component behind them. At least not in the sense that you got immediately compensated for behaving nicely. You did have social capital, i.e., the benefits of being perceived to be kind and nice and the opportunities that came with it. Social media made existence a performance theatrics gig that lasts forever. This is partly why on-chain media enthusiasts like to make everything mintable. So that people can sell digital assets (like NFTs) and earn.

But there is probably a middle ground. As cost and time needed for moving money reduces, every interaction on the web becomes a transaction. Your likes, clicks, scrolls and even DMs could be compensated in a token that is probably worth nothing, but is used to command attention. We are seeing early variations of this with MegaETH. The demo linked here shows a game where user actions are recorded on-chain in real time. Platforms like Noise are making it possible to trade how much attention goes towards a topic.

The story of the web is that of an attention economy evolving into a capital market whilst disrupting intermediaries.

Social media protocols like Farcaster have a role to play in it. And so do faster-paced networks like Monad and MegaETH. The individual chapters of this story are still being written. But here’s what’s apparent. For early-stage founders, knowing how to balance between value capture and velocity is where the secret sauce for survival lies. It does not matter if you have a million users if you do not know how to monetise them sustainably.

It appears, economic principles stick even when money moves faster than it once used to. In a future article, I will break down how Web3 social products and the creator economy will evolve in response to rising capital velocity in crypto. But for now, I go to the beach for a walk after a long day about stressing of how money moves.

Signing out,

Joel

thank you

What an outstanding and well written article