The Advertisers Are Coming

For your wallets and eyeballs

Hello!

About 80% of all venture dollars went into advertisements in 1998. A year later, ventures in the 'dotcom' sector spent more than $1 billion on ads during the fourth quarter – roughly equivalent to the combined spending of McDonald's and Burger King. In the same year, firms spent 94 cents on every dollar of revenue they made. With hindsight, it is safe to say that these expenditures were not sane. But that influx of money was crucial for the evolution of the web as we know it today. How?

Over 200 companies doubled their share prices during the dot-com bubble on listing day. The investors buying these shares came to know about firms through traditional advertisements. Consumer awareness around the internet rose substantially only because the possibility of speculatory gains (from listing) met a willingness to spend on ad dollars.

Most of that ad money eventually found its way into firms like Google and Yahoo, giving them a much-needed runway to develop the modern advertisement ecosystem.

Web3 had a close variation of this. Crypto.com and FTX purchasing stadium naming rights or Coinbase running a Super Bowl ad are examples of how an emergent technology tries using ads to purchase consumer mindshare. But while these initiatives did bring in consumer attention, the product suites within Web3 failed to retain them. Part of the reason was that we did not have mechanisms to identify, target and keep these users since their on-chain behaviour has not evolved yet.

We are entering some tricky territory here. As an industry, we have been opposed to collecting user data. But the more retail we go, the more pertinent it would become to understand the personas of users engaging with a product. Why? Because Web3 needs to transition from a transactional economy to one that can accrue attention if it has to house a billion users.

Ecosystems evolve when users can stick around without spending money. The internet exploded when users could listen to music, stalk their friends and stream movies. Web3, with primitives like Mirror, XMTP and Lens Protocol, is transitioning to a similar phase where consumer applications can scale without requiring users to make costly transactions.

But to onboard and retain user attention, the industry needs better mechanisms to surface and distribute relevant content.

As of today, content on Mirror is curated and displayed by the team at Mirror. You can use tools like Nansen to filter and surface interesting on-chain interactions, but no algorithms do these independently. Evolving advertisements as a primitive, in a Web3-native way, would be crucial if we expect the ecosystem to scale beyond the users betting on Rollbit today.

On the internet, the core primitive used to identify a user is their IP address. With blockchain-native applications, the identifier is their wallet. Platforms on the internet build context around age, spending ability and preferences through the use of cookies. In Web2, much of this data is siloed, so a new developer cannot expect to have access to that information.

By contrast, with wallet addresses, most developers do not have access to context. That is, they cannot know the preferences of a user. But everyone knows the finality of a consumer's decisions through their on-chain footprint. Visually, the two worlds look like the one shown below.

We need both worlds to blend for the ecosystem to mature and scale. Very few products are in a position to enable this transition. But before we get to them, it is worth observing how products target users today.

Parsing Transactional Behavior

The most primitive form of user identification and onboarding is checking a user's historical behaviour. Products like Degenscore allow teams to restrict access to wallets that have been early to other projects or moved large amounts of money on-chain. It helps teams reduce the number of low-value addresses interacting with a product. For instance, when Gearbox launched in the beginning of the last year, early users had to meet a specific score before accessing the product.

Such filters allow teams to vet out users who may not engage in large volumes while improving service for large depositors. A different way this plays out is with transaction volumes. Apps in DeFi often offer free trading or bridging costs if the transaction volume is above a certain threshold. Taking on these costs is justified for them as customer acquisition cost (CAC) is usually relatively high for their sectors.

Tools like Guild's Balancy Playground enable marketing teams to combine requirements of holding a certain number of tokens or NFTs to export wallet addresses that can be whitelisted for a product. The problem with the current model of identifying users is that products or content do not surface depending on a user's behaviour.

The on-chain ecosystem is isolated in terms of how apps or products are discovered. This is why a considerable part of dApp marketing involves paying accounts with large follower bases on X (formerly Twitter) to announce the release of a product.

A product that can evolve in this avenue is a notification system that studies on-chain patterns and surfaces alternatives. It could involve things like:

Observing a user is depositing tokens into Aave for a 4% yield but could get better terms elsewhere,

Flagging that a user paid 5% slippage on a Uniswap transaction and could likely have saved money using 1inch instead,

Or even tracking and notifying users of a new NFT drop by their favourite creators.

In such a model, the data used is entirely on-chain. Products that facilitate these notifications would need to understand a user's persona solely from their on-chain behaviour and surface alternatives that are better targeted. Wallet providers like MetaMask and Phantom are well-positioned to enable such transitions.

The tools in the market today, like Cielo Finance, parse through on-chain data and notify users when a third party does a transaction. The ability to feed a system one's transactional history and get insights regarding alternative products does not exist today.

An alternative approach here, is studying on-chain behaviour to sell off-chain financial products. It's far-fetched, we know, but consider this: If you want to sell a financial product to someone, you must know the person's risk appetite. You can try selling a fixed-income product to a crypto degen, but it will likely not work. However, combining off-chain knowledge with on-chain addresses gives advertisers a more complete picture of the consumer.

If the wallet owner owns blue-chip NFTs and has spent several ETH on gas (not sensitive to gas prices), they may be interested in portfolio management services. Conversely, a user who doesn't complete a transaction when gas prices are high is likely seeking value-for-money goods. As the lines between FinTech and DeFi blur, products that can understand a user’s on-chain activities to upsell off-chain financial goods would be well positioned.

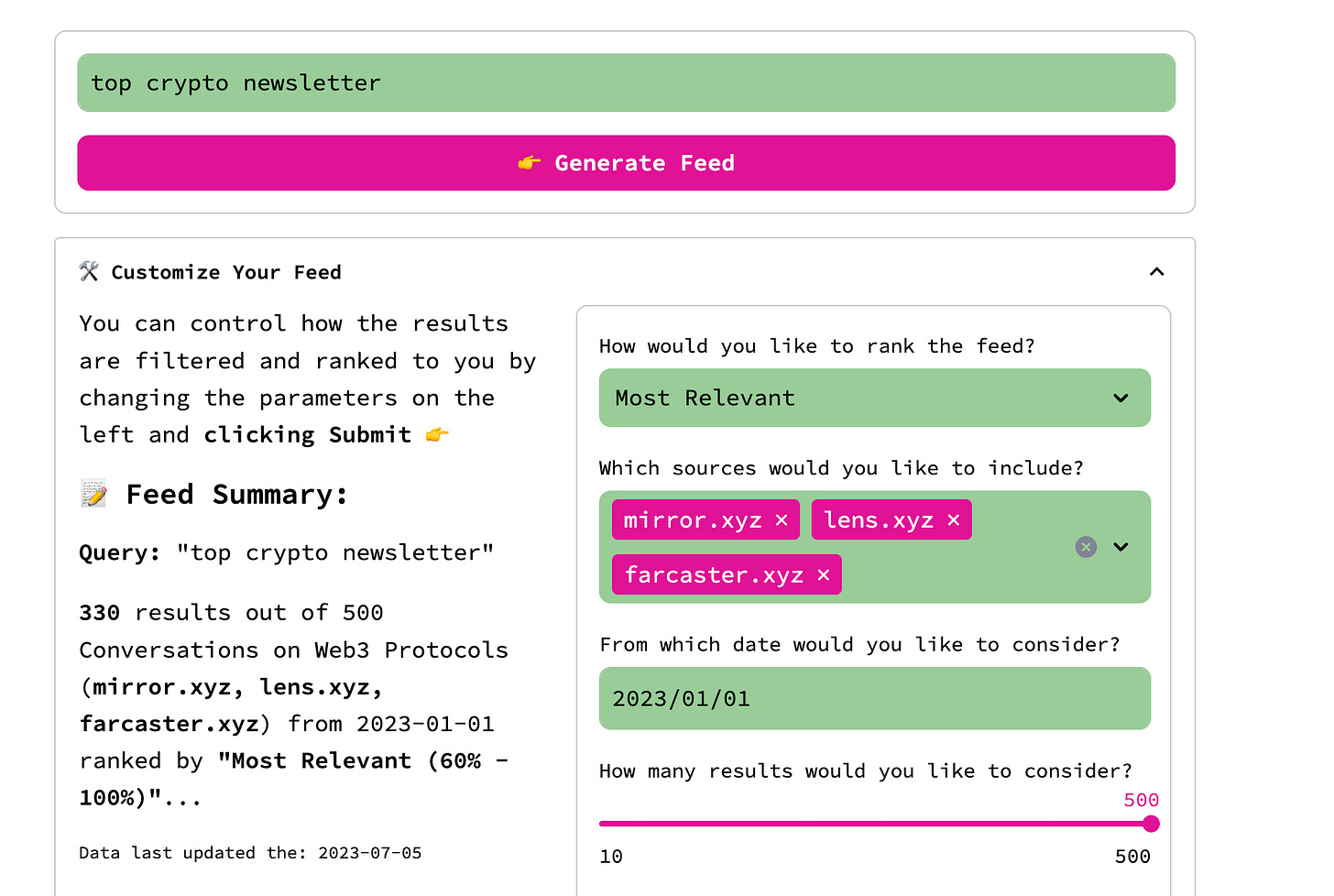

One place we witness this is with MBD.xyz. The product is more oriented towards content than it is to financial data. You can access their app right now and execute custom queries running across Mirror and Farcaster today. Think of it as a search engine for on-chain content. Although it is an early-stage primitive, it shows how content search engines evolve.

Someday, it is unlikely that users will go to Mirror, OpenSea, Farcaster or any number of new, decentralised content protocols. Instead, SDKs offered by MBD will bring content directly to a user's wallet. The user could mint, collect, trade or transfer on-chain primitives (like NFTs) directly from the wallet.

Why am I discussing discovery? Because unless you can map out what users are doing in Web3 today, you will be unable to surface more relevant projects for them. One place we are seeing what a Web3 native ad network would look like is with products like Brave Browser, Layer3 and Rabbithole.

Putting Users in Charge

In some sense, Brave has inverted the relationship between users and advertisers. They first started by blocking all ads. Then they began showing ads to users based on their opt-ins and rewarding them directly for doing so. A key differentiator between the ads users see on the browser, and the ones they see on Google is that Brave claims these ads are privacy-preserving and matched on the user's device.

The personal data never leaves the device. Brave crossed 50 million monthly users in 2021 (Google Chrome had 70 million MAUs in 2010).

For ad campaigns, it boasts an 8% click-through rate on its ads compared to the average of 2%. This means that when users choose to view ads, they follow through. The 6% gap may seem insignificant, but a purchase probability that is 4 times higher means about 4 times the revenue for every ad dollar spent.

With a lower user base, a high clickthrough rate may not mean much, but at the very least, ads are more effective when they are highly targeted and users are interested.

Applications like Layer3 and Rabbithole are onboarding platforms where developers and dApps are on the supply side, and users are on the demand side. Marketing teams for Web3-native applications use some of their CAC budgets to acquire users by giving them rewards in hopes that they will become permanent users.

But the question for marketers is – whether the ideal user for a product somebody who is also motivated by platform rewards?

The answer is debatable, but here is what these platforms do today. They aggregate a large enough user base for Web3-native applications to have a good top-of-the-funnel.

Only a tiny percentage of their users may be interested in a product, but that does not matter when they have a million users combined between them. For scale, Metamask, with its six years of dominance as a wallet, has only two million users trying their swap product today. Quest platforms commoditise similar reach levels for any marketer with money to spend.

The difference between Brave and platforms like Layer3 or Rabbithole is that for users, ads are an auxiliary activity when they use Brave so that they can stumble upon something new.

But Layer3 and Rabbithole are for users who have already decided to use Web3 products. These users could also be mercenaries just hunting for airdrops and rewards and may never become regular users.

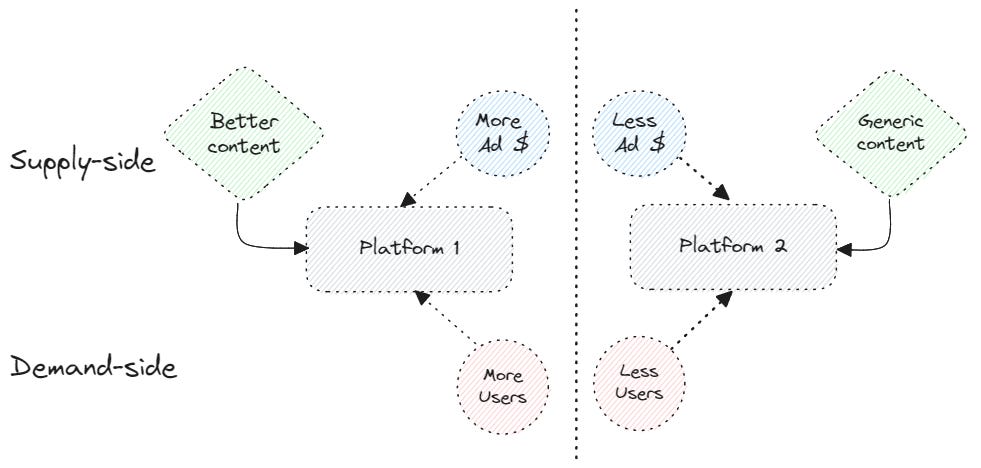

One way Web2 platforms scaled and managed to retain users is through empowering creators on their platforms. Bill Bishop of Sinocism was one of Substack's earliest creators. Lady Gaga was one of Twitter's earliest power users. Platforms and social networks act as matching engines between creators and users. Their supply side comprises content creators, and the demand side has users. Better content attracts more users, which in turn attracts more advertisement revenue.

What has typically been the way to attract creators? Making them growth partners is the most obvious one. If the platform grows, creators get a piece of the growth. But applications like LinkedIn and Instagram didn't stop at that. They created multiple auxiliary apps that help creators create new content so that their overheads are minimised, and they can focus more on new ideas.

In Web3 native content platforms, we do not have creators producing and distributing content as the consumers (eyeballs) wanting the content do not exist yet. One way platforms (like Mirror) could break through this chicken-and-egg problem is by incentivising creators through tokens or ownership directly.

Without good content, platforms are forced to incentivise users to stick around, which has often looked like fighting a losing battle. In Web3, we are paying people to watch ads. Isn't this similar to paying people to play games when it was already established that people pay to play good games?

During the early days of the web, it was evident that advertisements would be a core part of the new digital economy. Nobody knew how to value internet companies then, but one metric used was 'mind share'.

Even the number of times ads could be displayed on the Microsoft Windows boot-up screen were considered for valuation multiples. Two decades later, fortunately, Microsoft charges for a license and does not show ads on their bootup screens. Amazon is perfecting that heinous act with their Echo devices.

We are at a similar juncture with Web3. Nobody quite knows where ads could pop up. We have barely even indexed user behaviour to a point where it can be segmented and studied for retention. But here's what is likely to happen. In the age of on-chain content, everyone could query content from others, like MBD or Family Wallet does today. In such an instance, the only way a platform could create a large enough network effect of users interacting with a product is through

Onboarding creators through incentives (as mentioned above) or

Using data from users to combine intent and context to deliver superior experiences.

Products like Zerion and OpenSea today have millions of users interacting with their products. They are well-positioned to see what a user did on-chain and the number of times a user may have hovered around a new NFT or looked at a token's chart. They have both intent and context.

Such applications that have reached scale are in an advantageous position to begin advertising Web3 native products to users who opt-in. Given the composability of DeFi and NFTs, users will conduct transactions directly through their interfaces, and these platforms will register a fee for enabling them. But these are all hypotheticals. Any attempt to monetise attention in the industry may fail, given the industry's focus on privacy.

Two forces will be at play: teams' desire to grow at scale and market incentives for hyperscale. To scale, teams would need better mechanisms to target and retain users. Much like in the late 1990s, we will see money flow towards advertisement products again. It may seem far-fetched now, but it does not seem unlikely, given the emergence of consumer-facing applications in Web3.

I'll leave you with this chart by Ben Evans comparing print and digital ads to understand how quickly the tides change when a new medium emerges. On-chain data is rich, contextual and accessible. There are likely billions to be made through parsing it and enabling brands to better reach users.

Off for the weekend,

Saurabh

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

- Ep 14 - Antonio García Martínez from Spindl