0 to 10000000...

Cult formation in the age of attention deficit.

Hello and Happy New Year!

Today’s story is all about building brands and community. Dedicated to CMOs. If you are in the middle of building one, be it at a tiny startup or a billion-dollar protocol, make sure to get in touch with us using the form below or slide into our DMs. We like to hear stories as much as we like sharing them.

Building a career in marketing in Web3 can be a lot like building a house of cards. Marketing is hard. Now, add layers of technical complexity, sprinkle in a little frustration from dropping token prices, and for good measure, add a dose of fake news along with your family wondering whether you work with scammers. You get it—life can be hard when trying to build awareness in an industry where coders and traders get all the attention.

That’s why you need to work with people like you, even better if they are the ones behind the most recognized marketing campaigns in Web3. That’s what Safary Club offers. They are an invite-only network of the best marketers in Web3, working together to share notes, collaborate, and build an edge on how to translate piles of code into something the average person desires.

A few months back, Sid and I sat down to write a story filled with anecdotes aimed at founders looking to scale their marketing functions. We fumbled until we reached out to Safary Club. They were kind enough to introduce us to many of the brightest names in Web3 marketing. Instead of third-party references, this story features personal anecdotes made possible by the resources provided by Safary.

Make sure to follow Safary and explore their marketing intelligence platform, trusted by top protocols to drive growth

On to the piece ..

We live in the age of attention deficit. Founders building actual products struggle to find relevance in a market plagued by memes and AI bots. Build it and wait around long enough and you’ll realise nobody is coming. And yet, attention precedes growth. Building a business boils down to holding a person’s attention long enough to nurture a relationship that can be converted into a commercial transaction. Easier said than done.

Startup literature is littered with guideposts left by VCs explaining what it takes to build a business. Keith Rabois would argue one needs to be in founder mode. Paul Graham suggests doing things that don’t scale. A decade ago, Eric Reis said keeping ventures lean is the secret to growth.

A few months back, Sid and I began pondering what it takes to build, scale, and sustain meaningful brands with community elements.

While in pursuit of answers, we met Justin Vogel of Safary Club. A long-time reader of this publication, Justin has been building a curated community of some of the best marketers on Web3. Members of Safary Club are CMOs at some of the largest organisations within Web3. They run curated, close-knit batches for marketers, much like Y Combinator does for startup founders. Over the past month, we spoke to five CMOs in pursuit of writing this story. Think of it as a guidebook on how to think about brand building in your early days as a founder.

Over the next 20 minutes, we will distil years of learnings from CMOs who have built brands into household names. For ease of reading, I have broken down insights into what it takes at each step of the journey, from being active on Twitter to the perils of having a token as your native product.

This story wouldn’t have been possible without the following members from Safary taking their precious time to be candid about building distinct voices in a sea of noise.

Follow them, or even better, drop them a DM on Twitter, if these insights aid you.

On to the article.

Human Curated

Every day, nearly 82 human years' worth of content is uploaded to YouTube. In any given second, 2.4 million emails are flying, landing in our inboxes. The average person sees close to 10,000 ads everyday. We live in the age of digital abundance and attention scarcity. As choices scale, the trust required to make decisions do not scale in proportion to them.

Fortunately, we have always had a mechanism to filter through choices when many exist. We seek the expertise of others. Modern-day platforms curate in one of two ways.

One is algorithmic. A feed can be used to gather data on how individuals interact with a post and then be used to determine what content should go viral. Twitter, TikTok and Facebook use such an approach.

The other is human curation. One often prefers human curation. You could argue, this is the basis for how cultures have evolved. We do, what other humans tend to do. In the age of digital marketing, this translates to individuals following niche influencers. One of my favorite niche influencers is this man, giving good life advice on Youtube.

Most startups that launch do not have the ability to hire a niche influencer like MKBHD or Dave2D (both creators who have an outsized influence on which gadgets I buy) during their early days. What has been a time-tested alternative is going through platforms that allow sharing what one does in small, curated communities.

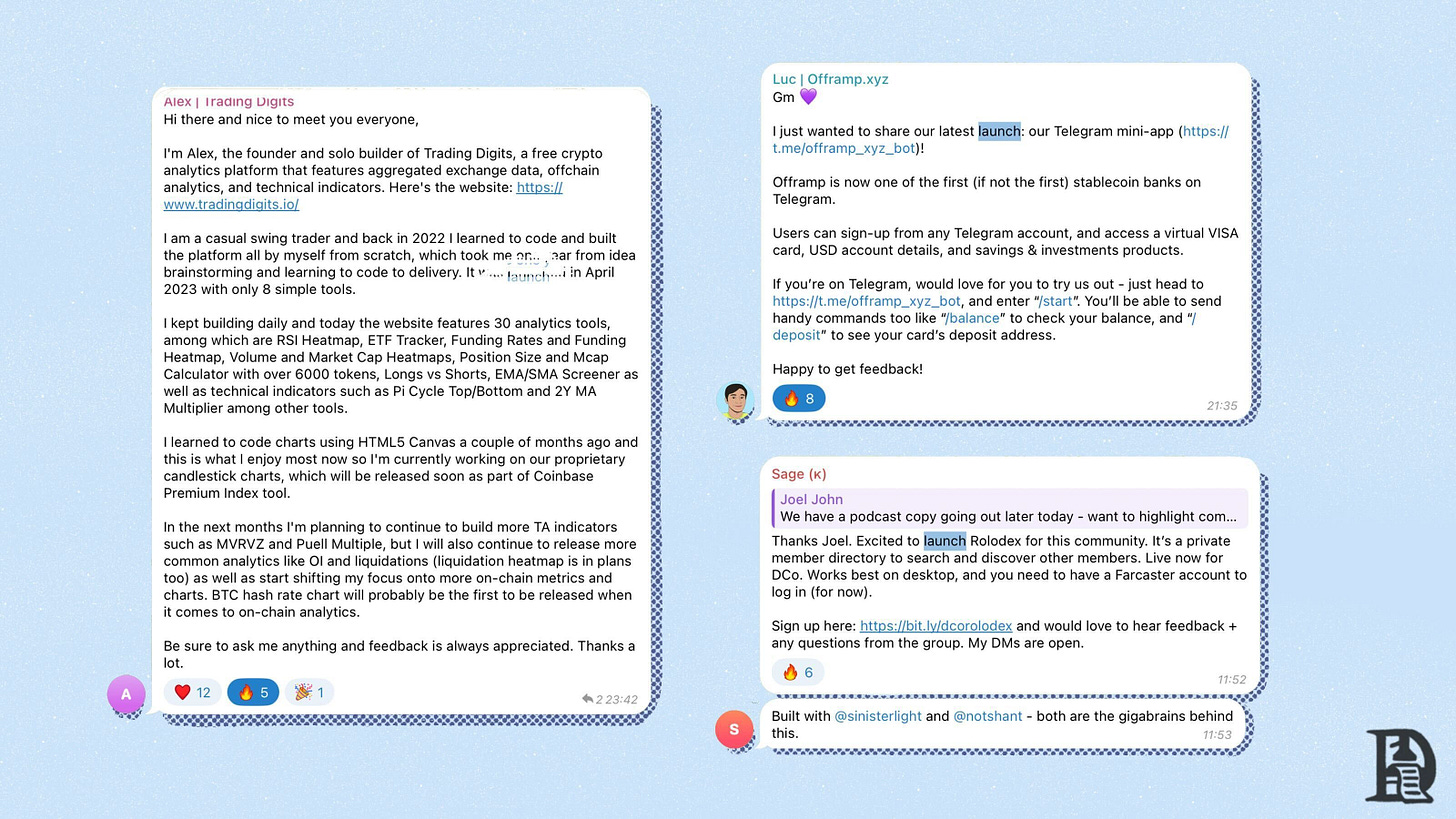

The lowest-hanging fruit for a venture trying to do this is through talking about what one is building in small chat groups. We routinely see founders launch their products in our own Telegram community of currently some 5800 members. Closed, curated communities are powerful engines for growth in the 0 to 1 stages as they allow meaningful feedback from an extremely curated subset of users.

Founders often abstract the personal journey when talking about a product in closed chats. Oftentimes, that comes off as meaningless marketing or a rude intrusion into personal space. Instead, what often works when scaling at this stage is to simply do a personal introduction, explain what the product does and how a potential user can get in touch. You could even make the process more personal by offering a free trial.

There is a fine balance founders need to juggle at this stage. If you market too aggressively, people will simply mentally block you. If you do not speak about what you are building, you become rapidly irrelevant. How does one maintain balance then? An often tried and tested approach in such situations is through giving meaningful value back to the community. People often discuss problems far more than they like to be educated on a solution. Sell the problem hard enough, and you have a wedge to pitch an alternative.

Giving communities value, even when it is not directly in line with the product a founder is building, lends a great amount of credibility to founders. It creates an early in-group of believers that endorse a product when a founder eventually decides to announce what they are working on. In such situations, playing non-zero-sum games and simply volunteering have disproportionate advantages.

People believe in people long before they believe in a brand. It is human nature.

The challenge with curated communities is that they often have their own rules of moderation and gatekeeping. Good communities are the byproduct of moderation. And moderation conflicts with the heavy demands that commerce often requires in closed communities. Go to any subreddit today, and try marketing a product in a way that is not personal and you’d see yourself quickly booted out.

So how do you scale once you have your first ten users?

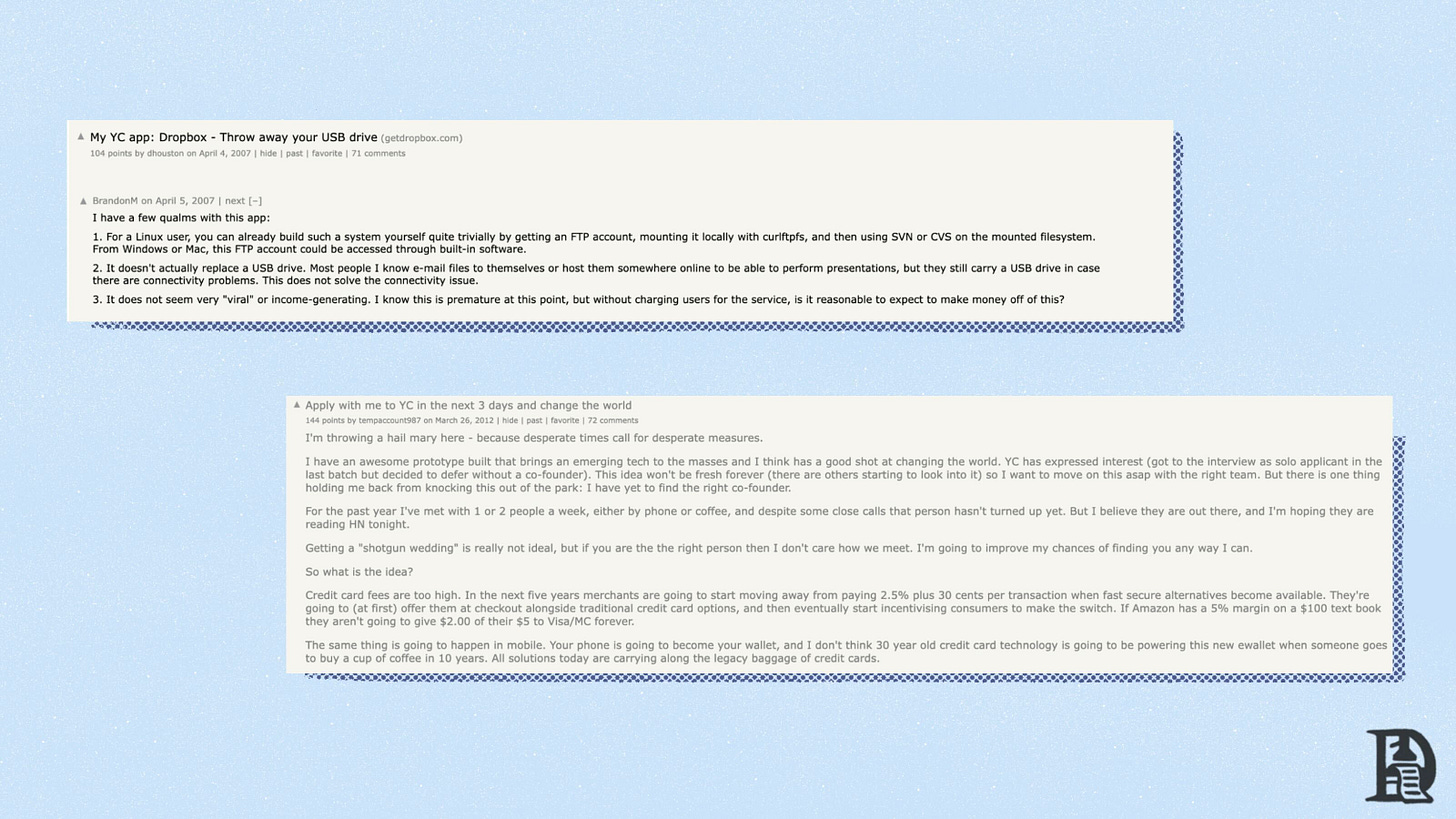

Y Combinator figured out the answer to this over a decade back. They created a curated forum for founders to “show” what they have been building. Both Dropbox and Coinbase were initially discussed on Hackernews. Producthunt is another platform that is often used to scale user bases. It was launched in 2013 by Ryan Hoover, now famous for running the 20MinuteVC Podcast. It was famously acquired by AngelList in 2016.

Human curation helps founders leapfrog the requirement of gaming algorithms for reach. But they also require authentic human relationships to be functional. It also requires founders to be willing to engage in meaningful discourse to win the confidence of a community.

Founders who believe they can simply outsource distribution at the pre-seed stages are often in for a rude awakening when they realise that a lot about selling is about relationships.

Sooner or later, these channels saturate. Most brands eventually need to trickle down to a social network (like X) to be able to scale. One of the people we engaged with to learn about how to build a brand on X is Dan Held. As of writing, he has a little over 744k followers.

Dan began building his presence on Twitter a little over half a decade ago. He was looking to build a following for his writing and quickly realised that Twitter was where all the distribution was. I asked him what his secret to building an audience is. And he told me in quite blunt terms—consistently shipping good writing for years.

Dan’s strategy has been to focus on educating the masses about contentious topics that are overly technical, and distills them down for folks to understand. Things like the energy consumption of Bitcoin, or how a fork of Bitcoin would play out. Whenever these controversies explode, there are very few research-driven analysts who consistently publish good content. Dan has been covering these topics in 1000-word pieces on Twitter for years. One of his “tricks” is to give up 5% of nuance to capture a 95% larger audience. That is, chopping down a bit to be able to capture the attention of a person on Twitter has worked well for him.

Dan was also a core educator in a strong community that has been rapidly growing. Between 2018 and 2024, the legitimacy of Bitcoin has grown by leaps and bounds. And yet, the number of research-driven analysts who can communicate in simple terms has not grown exponentially. So when he writes about Bitcoin from a position of legitimacy, the entire community rallies behind his content to help with distribution. They retweet and endorse it as a counter-argument to fake news that is often spread around on Twitter. This article from 2021 is a good example of how Dan breaks down FUD.

That position of “legitimacy” does not happen overnight. As Dan mentioned, his only secret is doing the same thing consistently, for years. Much like with small chat groups and human-curated platforms, Dan’s brand was not built by selling his Substack on Twitter. Instead, he was giving away value and contributing to a community with no short-term profit motive. The best sell is often made by not selling anything.

Dan told me that when he was in the early days of building his own brand, he sat down and compiled a group of words that would best describe him. If it were me, I’d probably write down ‘edgy’, ‘smart’, ‘accurate’, ‘creative’ and ‘sarcastic’. He would then seek out content that does justice to similar themes to build taste. What we consume dictates how we create. The top priority for Dan when he was starting out was to obsess about tone and delivery in a way most writers do not.

Dan focused on addressing the needs of an audience. Creators (or marketers) often fall into the trap of creating in their own parallel universe where nobody cares about what the person is trying to communicate. Dan’s approach was timely, helpful and well-researched on themes that are trending on Twitter. In turn, his audience made him into an authoritative figure who could speak about an emerging asset class.

As we’ll soon see, Dan has taken the same playbook to help co-build some really reputed brands within crypto. He has been the force behind names like Taproots Wizard and Mezo. I will break down his approach to scaling distribution in a later section. But, be it a personal brand, an NFT collection on Bitcoin or a Bitcoin adjacent L2, Dan’s approach to scaling distribution has been the same—to be consistent and authentic in giving out value.

Followers to Owners

Long before social networks became a go-to source for information, thousands of unpaid volunteers created the largest source of (mis)information (and bad references) on the internet. Wikipedia. Wikipedia’s most prolific contributor and a legend in his own right, has been contributing to the website since 2004. As of 2018, he had made over 2.5 million edits to Wikipedia, but the man had no claim of ownership to the site for his labour. It is almost as though he spent his weekends volunteering for free.

Be it miners on Bitcoin or stakers on Ethereum, incentive design is the art of getting stakeholders to participate meaningfully in exchange for rewards. But how does this apply to marketing?

In 2021, a major part of the reason for Axie Infinity’s run was the Play-to-Earn narrative. Individuals felt like they had a chance at converting their contribution to long-term meaningful ownership. Why does any of this matter in the context of marketing?

Nobody sells as hard as an individual that believes he is an owner.

Airdrop designs are powerful mechanisms to create a sense of ownership. Long before Hyperliquid’s tokens went live, they integrated a points system. The points hinted at the probability that a token would eventually be alive. It created a loop of users returning and engaging with the product for more points. First pioneered by Blur in 2022, points are a simple mechanism of giving users an indicative value for their effort without releasing tokens directly.

Where play-to-earn was a functional economy that needed to bootstrap both the supply and demand sides for the tokens or NFTs issued under them, points are a middle ground. They allow products to create a critical mass of users that engage with the product to give teams building them a feedback loop.

Naturally, not all users will contribute meaningfully enough to a network to be partial owners. A faulty assumption most marketers make is that a “community member” is a person who ultimately swaps on a decentralised exchange or provides data to a distributed mobile grid. Blue from Trader Joe has a different perspective on it. Trader Joe is a leading decentralised exchange that facilitates the swap of digital assets from one to the other.

In conventional terms, only a member that converts assets on the exchange is considered “valuable”. But Blue sees things differently.

According to Blue, every user that interacts with the product or its associated media assets (like Twitter, Discord or Telegram)is a community member. These users may not directly convert on the first go. In fact, they may not even use the product for a while. But they act as social signals for other potential users to eventually convert. The lines are blurry between a user who proactively engages on a chat outlet (like Discord) and an airdrop farmer. But this line of thinking explains the role questing platforms play in the early stages of community formation.

They make it possible for users who do not directly contribute resources to a network, to potentially build a small stake in an up-and-coming protocol.

According to Blue, the quest for such users has reached a saturation point. In 2021, given the extent of interest in DeFi, a protocol could build a community simply by building a product in the category. Attention and capital used to happily switch between products and protocols in pursuit of yield. But the story is vastly different in Q4 of 2024. Users have formed their preferences and the novelty in trying new DeFi primitives has largely waned.

So what do you do when a core audience subset no longer cares about what you’re building? You go to new territories.

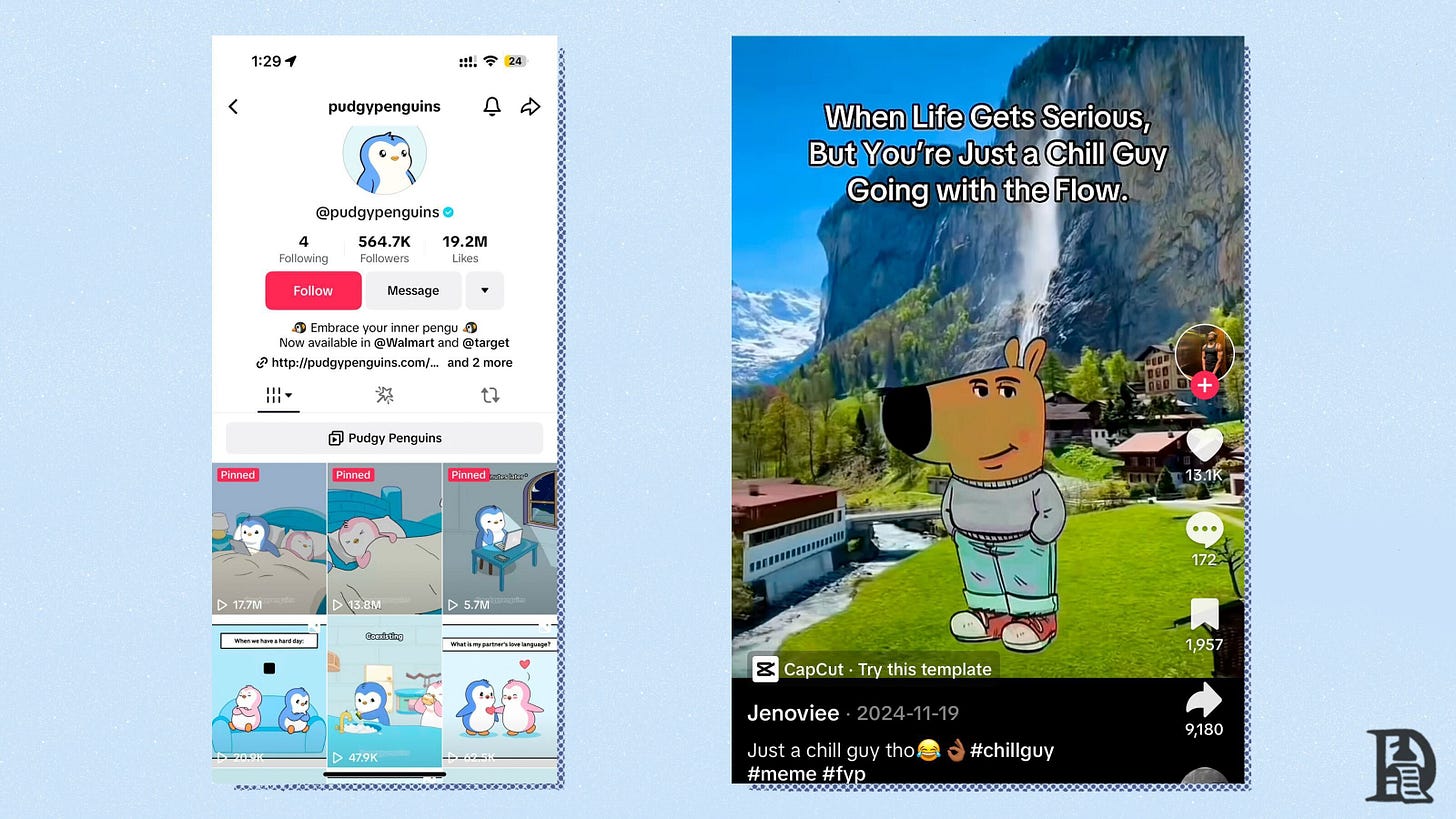

In fact, this is what Blue suggested he would soon be doing. According to him, the internet is transitioning to a phase of short-form content. For Trader Joe, this would mean exploring how YouTube shorts and Instagram reels could feed into their content strategy. We had this conversation in September. At the time, it felt odd that someone would argue for traditional social networks like TikTok to be a growth engine for crypto-native assets. Yet, in the months that followed, multiple meme assets like Chill Guy and PNUT found their footing deep in the trenches of TikTokviral videos.

Unbeknownst to me, Blue was predicting how attention would be captured within a matter of months.

Tokens like Chill Guy, Pnut and WIF may seem like a passing trend, but they show the power of capital coordination in the age of social networks. These are multi-billion dollar meme assets that emerged with no conventional VCs backing them. Meme assets, like other contribute-to-earn assets, have a sense of “fairness” to them. They give enough upside to individuals and thereby make them core proponents of a product. While founders cannot hope to make meme-assets out of their life’s work, there is a valuable lesson in how these assets operate.

If you make enough people sufficiently rich, in a short enough time frame, you may have to worry less about distribution.

Naturally, not all early-stage operators are equipped to make their community members rich. Perhaps, your listing is far off. Or even worse, you have no say in how a points system is run. What other levers can a CXO play with in such a situation?

I thought at length about it and concluded that ownership is not just about being able to trade or own an asset. It is about culture and the general vibe you get when you interact with a product.

Long ago, during the early days of Nansen, if you were an analyst tweeting about the product, you could expect a retweet from their handle. In some sense, it felt like leverage. Analysts were incentivised to make content using Nansen because they knew they would get distribution on the content. As more and more analysts saw their work highlighted through Nansen, the product became the defacto tool for investment funds to build a view of the market.

You could contribute content, to receive an incentive in the form of distribution. I know this because I used to be one of those analysts who built his social presence using Nansen years back.

Dune is another instance of a product that highlights its users. Prominent analysts like Tom Wan and Hildobby found their initial footing through the products they were contributing to. In these instances, the sense of “ownership” does not come from a stake in the underlying product itself. Neither Tom nor Hildobby were directly benefitting from the growth of Dune, but their reputation grew in tandem with that of the product.

Enabling users to build a reputation through a product is a different way ownership feeds into how people think of a product. Because, ultimately, our reputation is the one true asset we truly own.

Category Creation

All of the things I mentioned in the previous section require the ability to change the strategic focus of a product. Most individuals working on a marketing function are not equipped to “make their users rich” or issue tokens in exchange for using a product. Marketers often struggle to attract the most attention with the least amount of resources. This becomes particularly hard in nascent categories where nobody even believes there is a market to be developed.

In 2019, if you’d argued that BlackRock or Deutsche Bank will be tinkering with launching their own L2, you’d be laughed out of the room. And yet, in 2024, with the levels of maturity we see in RWA as a sector, this has become a reality.

Much like with content, category creation is also a relationship-based game. We learned this from Bhaji Illuminati, the CMO of Centrifuge. She has been a serial Lead on the marketing side for organisations that have gone on to be worth billions multiple times in her career. Early on, she noticed that when selling to businesses, a decision often rests with a single individual. These are usually CXOs who are routinely bombarded with proposals and little to no means of differentiating one proposal from the other. So how do you stand out?

An often overlooked fix to the problem is creating niche content that caters to a very specific category of decision-makers. For instance, we use RiseWorks to enable our team members to take their payroll in either crypto or fiat. In conventional terms, a payroll solution is not the most exciting thing to look forward to setting up. But I’d want to learn about how the best teams manage a global workforce.

Or what could be done differently to keep team members across cultures and time zones engaged as a first-time founder(there was no content I could find on this)? In Bhaji’s world-view, a team trying to sell HR tech would probably be best off creating niche content, especially in the format of a podcast to create legitimacy.

There are thousands of podcasts competing for human attention. And launching yet another podcast will not be the magical elixir that fixes all your distribution problems. But here’s what it does. It gives an avenue for smart, sectorial experts to come out and share their views in a way that does not require them to spend hours jotting down their best thoughts. When done well, a podcast invite is an avenue for a CXO to build their own brand.

So they tend to agree so long as these asks are within reason. More importantly, they tend to be a bridge that signals legitimacy.

Naturally, not everyone is suited to launch a podcast. If the matter is sensitive, it could not even be discussed in a public-facing media format. An alternative is to create small, curated working groups. In the process of researching for this article, I came across multiple individuals who created small, niche groups to further their own career goals and meet individuals working within their niches. Most prominent among these was Matthew Howells-Barby, the head of growth at Kraken.

He was an early employee at Hubspot back in 2014. During a career break, he set up a business that was oriented towards bringing together professionals with a focus on growth roles at startups. This is the opposite of what a podcast is. Instead of relaying expertise to anyone who streams into an RSS feed, a closed slack group compiles a small subset of users with niche expertise. The psychology behind why such groups work is simple.

Individuals often have career-related queries that may not be aired in an open forum. At the same time, they may need high-quality advice that is specific to a role they are serving in. Who does one turn to?

Matthew identified this gap for growth-oriented roles back in 2020 during the COVID lockdown. In 2021, the business was sold to SEMRush. Interestingly, this article came together as the result of Justin (from Safary) serving a very similar role for marketing-related roles. When CMOs struggle to vet a vendor or need perspective on how a potential campaign might work out, Safary’s network of over 300 marketing professionals acts as a sounding board.

Creating closed rooms for collaboration helps lend legitimacy to a core product that is trying to find a user base without necessarily selling aggressively.

While both podcasts and private groups help identify niche decision-makers, they do not entirely help create new categories. Remember the example I took for RWA’s in 2019? Nobody quite believed that loans or real estate would transition to being entirely on-chain at the time. We are in a similar phase with autonomous agents such as the ones enabled by Virtuals or Ai16z today. Nobody quite thinks that agents will be primarily responsible for most on-chain transactions today. You could see a variation of this with Web3 gaming too.

In such nascent categories, firms are best incentivised to rally together and create working groups. Bhaji from Centrifuge faced this conundrum while trying to build out legitimacy for her own protocol. She had to bridge the two entirely disconnected worlds—that of blockchain primitives and traditional finance. That too at a time when there was little confidence in what blockchains could do for finance. In order to get around the problem, she started setting up the Tokenised Asset coalition in collaboration with a few large names like Coinbase and Circle. The coalition started with seven founding members.

Its core mission? To educate and spread the word about what the eventual arrival of RWAs on-chain could do. Such coalitions help expand the pie instead of competing for a very small, niche market. Bhaji said that in a recent call for applications, the coalition saw over 700 firms applying to be a part of it. The reason why such coalitions tend to work is because they are able to communicate in ways that are true to the niche, as opposed to the industry. Instead of talking about “aping” into a DeFi pool, you might have to structurally break down the transactional efficiencies that come with issuing a loan on-chain. Very few market participants are able to do that. Coalitions like the one created by Bhaji are able to do that and thereby find themselves in enviable positions.

Naturally, the next step once you have these curated communities is to create environments for active discussion, collaboration and commercial partnership. A lot of time slack DMs or Zoom meetings do not facilitate that. Both Safary and Tokenised Asset Coalition branched out to real-life events to further facilitate relationships. A lot of times, deals in crypto are made with pixels and bytes.

Real-life events help put a face to the handles we see online. For Bhaji, this meant organising a Real World Asset summit. For Justin from Safary, this meant organising a meetup for his own community. Both marketers emphasised the need to enable human, in real-life interaction for building community in small niches.

Be it Dan Held trying to build an audience for bitcoin native content or Matthew Howells Barby building a curated audience for growth-related matters, relationships form the barebones of effective selling. One cannot build community without being consistent, authentic, true, and to a certain extent, selfless. This is at odds with the pace at which a startup may want to grow. Investing time into an asset coalition may be a hard pitch internally if you are working at an early-stage startup.

And yet, if I look at what either Justin, Bhaji or Dan did, a common string arises. They focused heavily on selflessly giving away value long enough to build legitimacy and reputation. In turn, it built a flywheel of trust that accelerated what they were trying to build.

Attention is All You Need

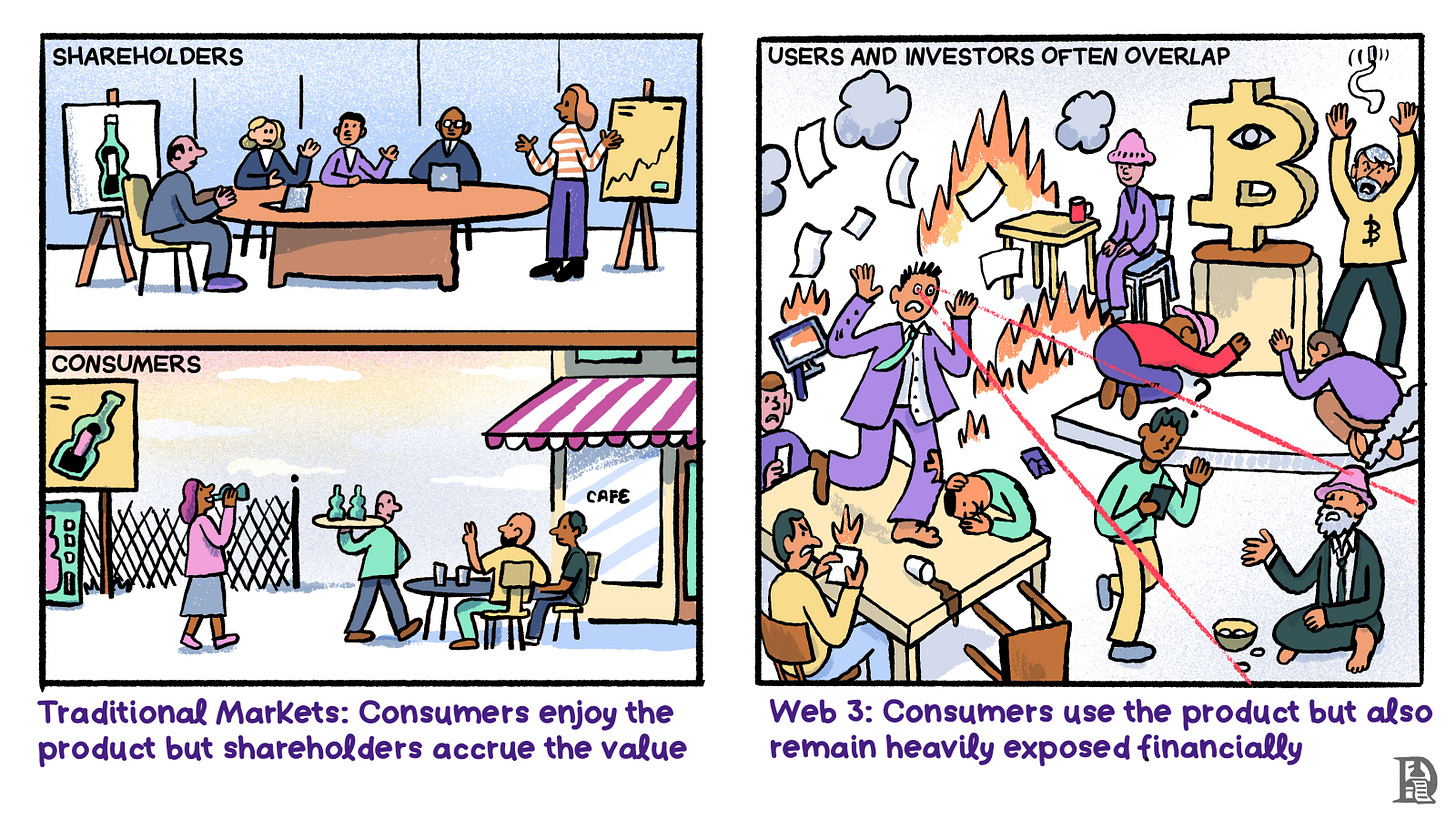

A repeat mistake marketers often make is confusing allegiance to a token, with that of a product. Matthew from Kraken drew an interesting parallel to explain this situation. When you buy Coca-Cola, the drink, your only interest is in its ability to blast dopamine through your brain cells with the sugary overload it induces in your body. Worrying about Coke’s share price is an institutional investor’s concern. Warren Buffet’s, perhaps. In crypto, the user and the asset are intertwined. Most users come for the asset. And oftentimes care little about the underlying product itself. This is probably why much of Web3’s userbase is found on exchanges, and not in its dApps.

But how do you find users at a time when most attention is on the asset itself? Andrew Saunders from Skale had several strong views on this. According to him, the first goal for a marketer is to form sticky communities. The kind that do not leave after a quick airdrop or incentivised testnets. In order to reach them, you have two tools at play. One is using influencers. For individuals who are not close to the marketing side of a business, KOLs may have an odd tone to them. But using a celebrity to build a user base has been core to how tech cycles work.

In 1995, a few months after Friends (yes, the TV show) launched, Matthew Perry and Jennifer Aniston did a session on how to use Microsoft Windows. In 2002, Will Ferrell did a commercial for the iPod. And then there is this advertisement done by Jay-Z for Rhapsody. You get the point. Celebrities can make technology ‘hot’ in its infant stages. But most marketers do not have the budget to afford these names. So what do they do? They go with crypto-native alternatives—creators within Web3 that have massive reach. And this is where much of the interest in KOL engagement comes from.

The problem with doing KOL deals is twofold. One is that often they do not make the necessary disclosures required to their audience base. The other is that verifying whether the quality of a person’s content meaningfully educates the right audience subset has historically been hard. Quite recently, Kaito has been making waves by giving marketers the ability to vet creators. Kaito algorithmically verifies the reach, quality of interactions and frequency of a creator and gives what is referred to as a Yap score. The score is a quantified (albeit centralised) score of how “useful” a creator’s content is. This helps ensure protocols incentivise the right users.

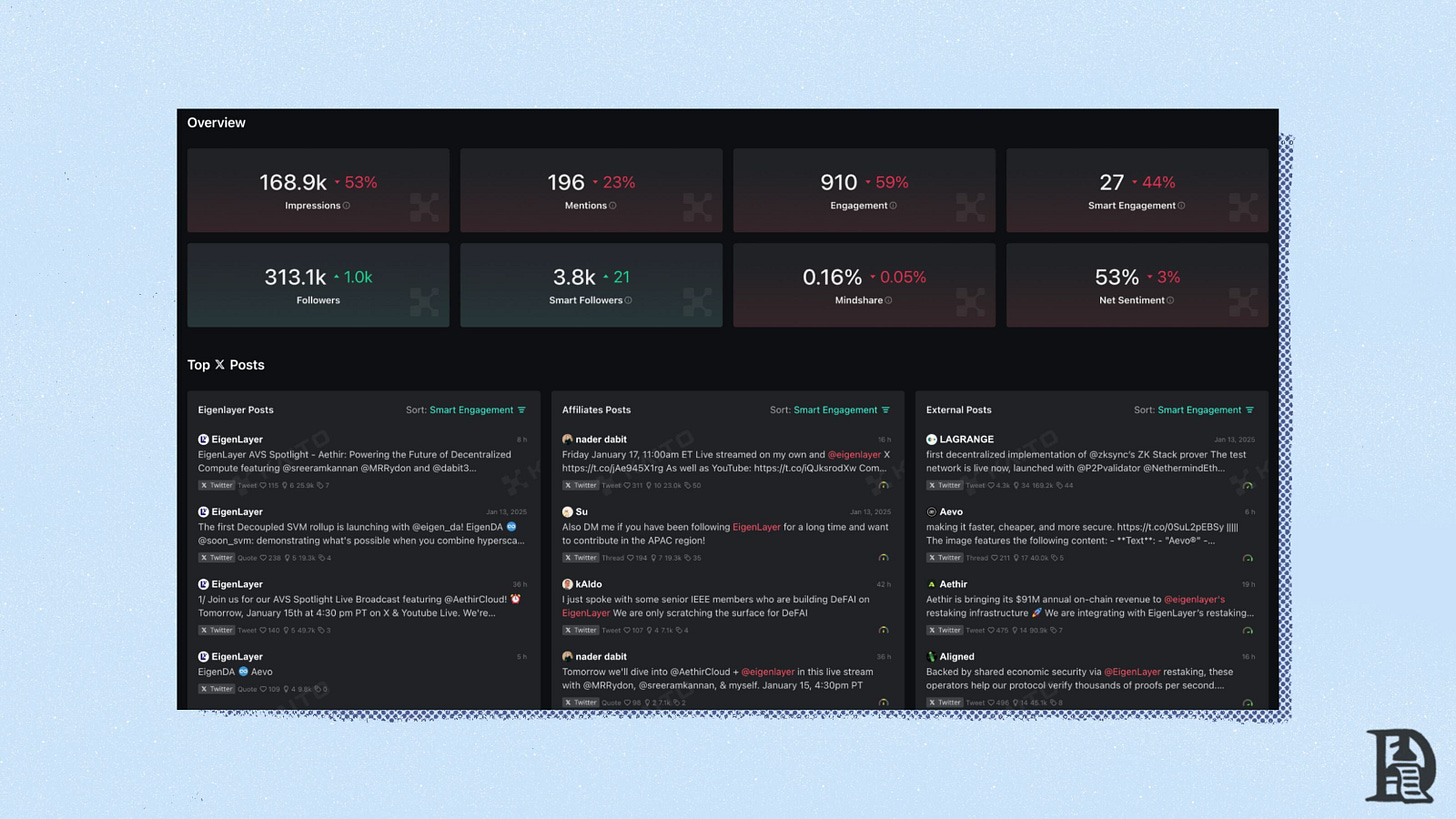

Kaito also makes it possible to have a protocol-native Yap dashboard. So if you are say Monad or EigenLayer and you’d like to know who your top ‘Yappers’ (or contributors) on social media platforms are, the platform maps them out for you. Marketers can then use these scores to incentivise creators using airdrops. These are still early days, but it is safe to say that Kaito has meaningfully made a dent in how users are educated and creators are discovered. This is not to imply that a marketer’s job has gotten drastically easier with their dashboard. Oftentimes, spreading a story and onboarding users requires as much emotional intelligence as it requires raw data. One of my favourite instances of this came from Andrew’s experience.

Note: Decentralised.co is one of the largest holders of Kaito’s NFTs. These were given to us as part of an airdrop for paying subscribers to the platform. We have been users since Q1 of 2024.

He used to work with Amazon during an earlier phase of his career. Part of their marketing policies was to not work with individuals who have been arrested. At a certain point in time, the firm decided to engage with multiple hip-hop artists for the marketplace’s outreach. Given the high frequency of arrests among hip-hop artists, Andrew had to work towards changing internal policy for the campaign to go through. At that point, he’d reached the final stages of what it takes to onboard creators. Changing culture. Oftentimes, firms (or protocols) have policies that deter good creators from coming on board and helping spread the word about a nascent technology.

Marketers who have sufficient influence working on early-stage protocols have the ability to define their own culture. Dan Held (of Asymmetric) was famously involved with Taproot Wizards. Part of the requirement for a person to be able to mint a wizard was taking a picture from their shower. Whilst most communities would drop the requirement for a large influencer or investor, Taproot held true to its promise. Every member in the NFT community had to go through the same embarrassing process to be able to mint an NFT. Much of Taproot’s public-facing communication follows the same quirky energy that seems quite disconnected from what one would consider conventional marketing. But it helps nurture a culture that is true to the community. The same is reflected in their manifesto.

Very few marketers have the capability and influence required to make a bet on emergent creators. Too often, the work is not in being analytical about click-through rates or the number of views. It is in being able to have a taste for the impact a stand-alone creator can bring to the equation.

In 2008, Barack Obama made history by being one of the first Presidents to be elected primarily through attention garnered on social media. He was a young politician who banked on an emergent technology to aid his campaign. In 2024, President Trump garnered great amounts of support from crypto-native backers, who were single-issue voters. In both instances, an emerging technology had a meaningful impact on the fate of a nation.

Between the continuing drama that unfurls on Twitter and the emotions induced by price drops, we fail to realise that ultimately, crypto’s success banks on its ability to onboard users.

This hits marketers even more as they are often the first to be let go in a downturn and struggle to quantify the direct impact of their work. But our industry’s evolution from Silk-road- currency to the mainstream has largely relied on the ability of marketers to translate code into stories that stick in people’s minds.

If we are to onboard the next billion, they will simultaneously have to be empowered, cherished and celebrated.

Signing out,

Joel

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

- Ep 31 - Web3 Marketing Playbook with Phin from Abstract

- How To Build Product-Community Fly Wheels