Attributions in Crypto

Where do the clicks go?

Hello!

Today’s story explores how a Web3 native ad network would emerge. If you are building along these lines or thinking about alternative monetisation models for the web, make sure to get in touch.

Three DCo members fit the typical Indian stereotype as far as career arcs go. Most Indian kids complete engineering, then either go abroad for a Master's programme or, like us, enter the rat race to get into some of India’s most prestigious management institutions with a ~0.1% chance.

Yet here we are, leaving behind cushy traditional jobs from our campus to work in an industry that’s in no way traditional, where the sentiment swings between ‘it’s all over’ and ‘we’re so back’ every day.

Come to think of it, none of us would be in crypto or Web3 had it not been for free Web2 content. I learned about crypto by watching Andreas Antonopoulos’ YouTube videos, reading Twitter threads, and consuming articles on Substack, almost all for free. Today, we make our livings partly due to our degrees but mostly thanks to the free content we consume on the internet.

Free content runs the web. But in order to make something “free,” you need to be able to attribute value to the eyeballs that pay attention to it.

Today’s issue is a follow-up to our podcast episode with Antonio from Spindl last week.

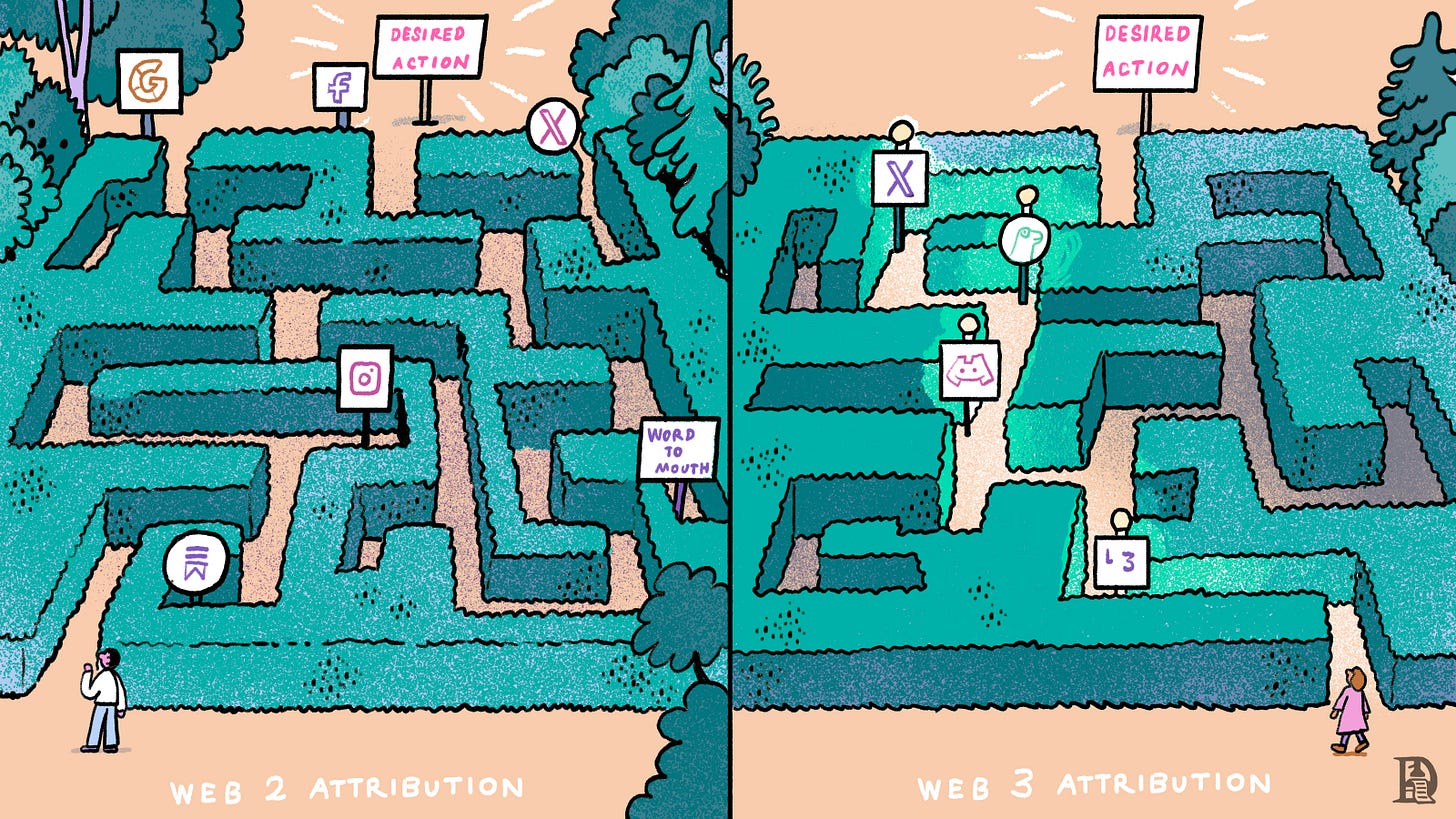

This article is about the influence of ads on our online experiences— how marketers track a user’s journey from click to purchase, and the rise of Web3 with a potentially game-changing approach to ad tracking.

Ads Pay For The Web

When something so good is free for you, you often ask who pays for it. Mostly ads. We have a few paid subscriptions here and there, but most of the content is subsidised by advertisers who are trying to reach their consumers through different digital media. Advertisers (brands) run their ads through various channels. Some of these channels convert. A conversion is when the internet user sees the ad and buys the product.

Most creators on the internet have two ways of monetising - either put your content behind a paywall or let it be free for everyone and monetise through ads and sponsored content. Almost all creators choose the same unless they have other well-established sources of revenue. We can all hate ads and growth marketing but it has played a critical role in growing the internet to its current scale of billions of users.

Web2 scaled rapidly and had a billion users before it struggled with clear business models. Web3, in contrast, has clear business models but struggles to find enough users.

For context, Google made $237 billion in revenue from ads out of its total revenue of $307 billion in the year 2023— a staggering 77%. Twitter made around 75% of its revenue from ads during the same time. Internet giants stand tall on the pillars of advertising. But marketers need to know what an effective advertising channel is. If you don’t know the per-dollar-ROI of spending money on an ad, what is the point? Otherwise, they just shoot in the dark and pay publishers like Google and Facebook for pure randomness.

Determining How Effective Ads Are

There needs to be a mechanism that helps advertisers identify what caused a user's action. For example, I read a book recommendation on Substack but am not considering purchasing the book. I see the same recommendation in a YouTube short, but I’m yet to act on it. Joel mentions the same book in our conversation. Finally, I purchase it when I see an ad while scrolling through X (Twitter).

What really led to conversion here?

Was it only Joel’s recommendation? Did YouTube, Substack, and/or X play a role? Attribution tries to answer these questions. As the AdTech world evolved, so did attribution, aka infrastructure for tracking and analysing marketing campaigns.

Brands try multiple ways to reach out to their prospective customers. Some ways are more effective than others, and brands want to know about them. These channels give them more bang for their buck. Finding various touchpoints that make the user convert and assign them credits is known as attribution in advertising.

Philosophers like Socrates and Aristotle have long tried to analyse human behaviour and answer the question, ‘Why do we do what we do?’ In the 1950s, Fritz Heider, known as the father of attribution theory, was the first to focus on how people explain the causes of behaviour and events.

Understanding the trigger behind an action plays a critical role in advertising. Measuring advertising efforts leads to wise spending on different channels. This is where attributions in advertising start. Traditionally, attribution tries to answer questions like how much to spend on newspaper ads or whether to purchase a commercial slot during a cricket match. It is quite difficult to understand the impact of advertising in the non-internet world.

The story is quite different on the internet. When a user clicks someone’s referral link, the seller can know which referrals convert better. When an advertiser knows that Instagram gets them most converts, they can reduce spending on offline channels. When you do grocery shopping in India on apps like Zomato’s Blinkit or Swiggy’s Instamart, they track which items you search for, which were impulse purchases, items you removed from your cart.

Right from the time you log in till you leave the app, every tap you make is recorded and analysed to understand your behaviour.

Evolution of Attribution

In the era of only print media, advertisers had to resort to things like coupon codes, dedicated phone lines for specific ad placements, running ads in specific regions, and comparing sales to understand the impact of their campaigns. Publishers charged advertisers on the basis of the dimensions of the ad, the page on which the ad was printed, geography, and other such factors.

In the 1990s, computers and the internet happened. But advertisers didn’t know how to measure the impact of their ads on websites. The first ever ad on the web was in 1994 by Wired. It was just like the ads you saw in the print media but on computer screens.

It was just a banner. Apparently, it had a click-through rate1 (CTR) of an outrageous 44% compared to the average of between 0.4% and 0.6% today. Despite the change in the medium, the strategy remained the same— flood the websites with as many ads as possible and hope for the conversion. Cost per mille or CPM was a ubiquitous model wherein advertisers paid publishers for every 1000 impressions. There was no way to understand whether users clicked through these disturbing banners to make a purchase.

In the early 2000s, Google changed the game with cost per click (CPC) as their business model. This meant Google only charged the advertiser if the user clicked on the ad. It didn’t matter if the user made the purchase. CPC was better than CPM because a click was more valuable than a user just seeing the ad.

The first time we measured an ad's impact was around 2009 with the cost per install (CPI) model. Under the CPI model, the advertiser paid the publisher only when the user installed the application. This performance-based model ensures a more direct return on investment (ROI) measurement for the advertiser. On the other hand, a malicious publisher may employ bots to inflate the number of installs artificially.

Installation is not the only action that warrants advertisers' attention. It could be a sign-up, purchase, or installation. In the Facebook era, around 2013, cost per action (CPA) became the advertising business model inside the advertiser’s app. CPI was a subset of CPA. This is how we entered an era where advertisers could mathematically verify the relationship between their ad spend and revenue generated.

All the models described until now have a risk associated with them for the advertiser. Here’s the mathematics of advertising: you spend a few dollars to acquire a customer, known as the cost of acquisition, or the CAC. The acquired customer then spends some amount of money on the advertiser’s product or service. This is the user’s lifetime value or LTV. The advertiser needs to ensure that LTV > CAC.

What if the publisher somehow tampers with the attribution numbers? What if the user never spends money towards the advertiser? Can advertisers run ads through different publishers in a risk-free manner? Enter Cost Per Value (CPV).

Remember the discussion about who my book purchase should be attributed to? There’s a concept called multi-touch attribution (MTA). Ideally, all touchpoints should be rewarded instead of picking a single winner like the Googles and the Facebooks of the world do. But how do we know all the touchpoints?

Tighter norms on user data monitoring mean that advertisers may be unable to track users for longer durations. For example, if you see an ad now and purchase or subscribe to something a couple of weeks later, the ad may not get the deserved attribution.

This is especially true in the case of dominant search engines like Google. Even though the consumer had already made up their mind about the product, they searched for it on Google for the website. And Google becomes their last touch point. In Google’s books, they made the final convert. But in reality, the decision to make the purchase was already made.

User actions are more persistent on-chain than just online. You know whether the same wallet address that saw an ad purchased an NFT, provided liquidity, purchased a token, or voted on a governance proposal. But you don’t necessarily know that the same user saw an ad on Facebook on their desktop and purchased the product from Amazon on their phone.

The most powerful thing about the CPV model is that it turns the ad budgeting problem upside down. Previously, you had to spend money first to see if the user converted. With CPV, you spend the money only if the user takes actions you deem worthy. A combination of off-chain and on-chain tools will allow advertisers to share the spoils with the entire value chain, including the end user, making advertising a net positive exercise.

One can argue that the CPV proposed by Spindl is akin to affiliate marketing in Web2. Both are performance-based. But they differ in complexity, i.e., how they define and measure performance. Affiliate marketing is more direct, whereas CPV can be more nuanced. For example, let’s say an affiliate is supposed to get a 10% commission on every purchase through them. But what if other sources are also responsible for the conversion? The CPV model aims to capture them and distribute the rewards based on the contributions of different channels.

How Web3 Helps

Blockchains are ever persistent. If a user takes an action on-chain, it remains there forever for everyone to see and verify. The number of active users in crypto is significantly lower but the LTV can be into thousands of dollars. This permanence and transparency, combined with the high LTV of crypto users, creates a unique landscape where every interaction holds immense potential for marketers willing to leverage blockchain data effectively.

Say a user sees an ad from one address2 and takes action through a different address. In this case, a few tools together can tell the advertiser whether their ads played a part in the user’s decision. Products like 0xppl, Arkham, or Nansen that help in mapping user addresses can probabilistically tell whether both addresses belong to the same user.

On the one hand, there’s a developer or group of developers who have the money (tokens) and want users’ attention, and on the other hand, there are publishers who want user attention and money. But can developers trust publishers to give them accurate attribution? Obviously not.

There should be a neutral third party that works for advertisers to get them attribution that measures how their CAC has translated to LTV. This is what the likes of Qwestive, Safary, and Spindl are doing.

Here’s how it works in Spindl’s case—there’s an on-chain ad campaign contract. This helps advertisers design their campaign rules, desired on-chain actions they are willing to incentivise, and so on. The attribution protocol measures the impact of different channels like affiliate marketing, publishers, and KOLs and decides who should get how much.

When the user converts, the smart contract shares a bounty with every stakeholder in the value chain.

The on-chain attribution platforms are not fully evolved to handle the Web2 level of complexities where the user moves from one website to another, one device to another, and different browser sessions. The upcoming product from Spindl is a growth protocol devoid of opinion. I think the DNA of the protocol dates back to Antonio’s efforts to create an Ad exchange at Facebook.

Antonio mentioned on our podcast that when he was starting out Spindl, many Web3 advertisers (think application or protocol developers) seeking users had no idea of their metrics like CAC and LTV. These numbers are something that Web2 founders start and end their days with.

For a sense of scale - the Internet advertising revenue (Web2) grew from $7.3 billion in 2003 to $224 billion in 20233. Although it’s difficult to pinpoint Web3 ad revenue at this stage, we can safely assume that it is much lower than the total ad revenue of Web2 in 2003. So, as far as Web3 advertising is concerned, we are probably in the early 2000s.

What can the future look like?

What edge does Web3 have over its predecessor? To me, it is the user insights based on an open ledger. Imagine precise user personas without invasive tracking. Targeting based on actual spending habits, not clicks. Efficient and relevant ad tracking without too much guesswork. Web3 infrastructure offers unprecedented market segmentation, potentially revolutionising how we view and interact with online advertising.

There are businesses that are facilitating such a transition from click-based commerce to one that is able to track financial outcomes from public ledgers here today. We will be writing a long-form on them in the coming weeks. Ads enabled monetisation and discovery for the web. For what it’s worth, they did the same for newspapers and radio too. Across mediums, advertisements are a necessary evil. Commerce requires capturing eyeballs, and convincing a product is a necessity.

The reason why Instagram or Facebook have been so effective at doing ads is the extent of data they hold on users. As public ledgers (blockchains) become more commonly used in commerce, we will quite possibly have open-ad networks. Ones where multiple publishers can target the same user. It remains to be seen how spam could be filtered, or how sybil detection could happen when such ad networks scale.

Reach out to us if you have been thinking along these lines.

The web needs rebuilding.

Thinking about restaking,

Saurabh Deshpande

Shows the percentage of users who clicked on the ad displayed

The advertiser knows when an address is connected to a website via a wallet like MetaMask. The website can record that an ad was served on the page where the address had logged in. The advertiser can also track ad impressions via traditional methods like monitoring cookies.

Please note that Google’s ad revenue, as per the annual report, was $237 billion, and the total ad revenue on the Internet was $224 billion, as per the IAB/PwC report. The discrepancy is likely due to what IAB considers as ad revenue.

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

- Ep 14 - Antonio García Martínez from Spindl