Pricing the Internet

Programmatic payments vs Ads

Hello,

There are two distinct schools of thought in crypto. As a publication, we get to have a front-row view of both. One argues that everything is a market and pricing things is how we get clarity. The other believes crypto is better fintech rails. Our publishing calendar swings between both views because, as with all markets, there is no single truth. We are simply curating all possible models.

In today’s issue, we have Sumanth breaking down how a new payment standard is evolving on the web. Put simply, it asks the question: what would happen if you could pay per article? To find the answer, we go back to the early 1990s and see what happened when AOL tried pricing access to the internet on a per-minute basis. We walk down the alley of Microsoft pricing its SaaS subscriptions. And eventually, we sit at a cafe where Claude has been pricing conversations on a per-text basis.

In the process, we lay down an explanation of what x402 is, who the key players are, and what it means for platforms like Substack. The agentic web is a theme we have been increasingly exploring internally. If you are building, researching, or investing along these themes, reach out to us at venture@decentralised.co.

Joel

The Internet’s business model is out of touch with how we use it. In 2009, the average American visited over one hundred sites per month. Today, the average user opens fewer than thirty apps per month, yet spends far more time inside them. About half an hour a day then, closer to five hours now.

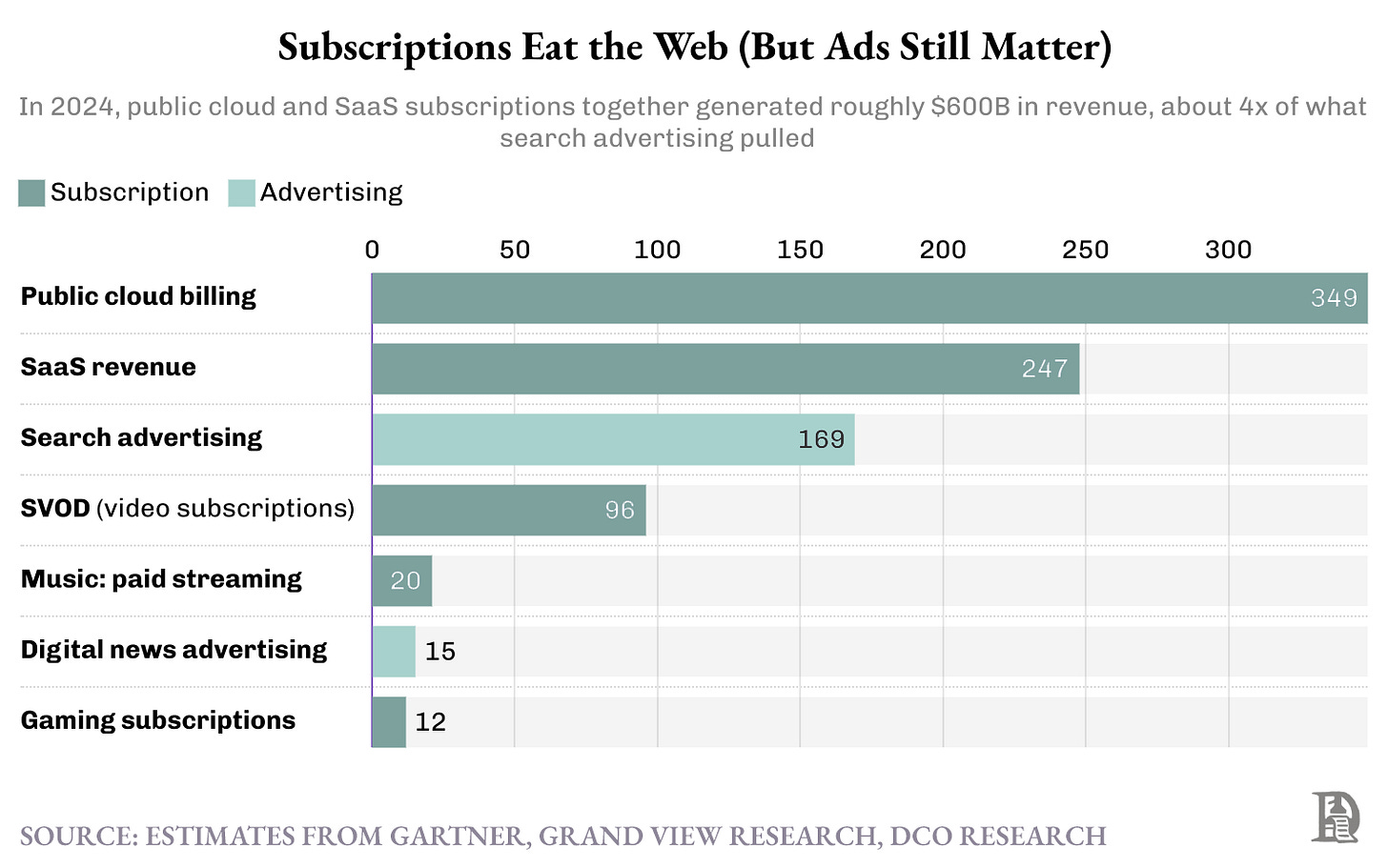

The winners - Amazon, Spotify, Netflix, Google, and Meta, became aggregators who pooled consumer demand and converted wandering into habits. They priced those habits as subscriptions.

This works because human attention follows patterns. We watch Netflix most evenings. We order from Amazon weekly. Prime bundles include shipping, returns, and streaming for $139/year. The subscription removes much of the constant pain. Amazon is now pushing ads to subscribers to juice margins, forcing users to sit through the ads or pay more. When aggregators can’t justify subscriptions, they fall back on advertising like Google, which monetises attention rather than intent.

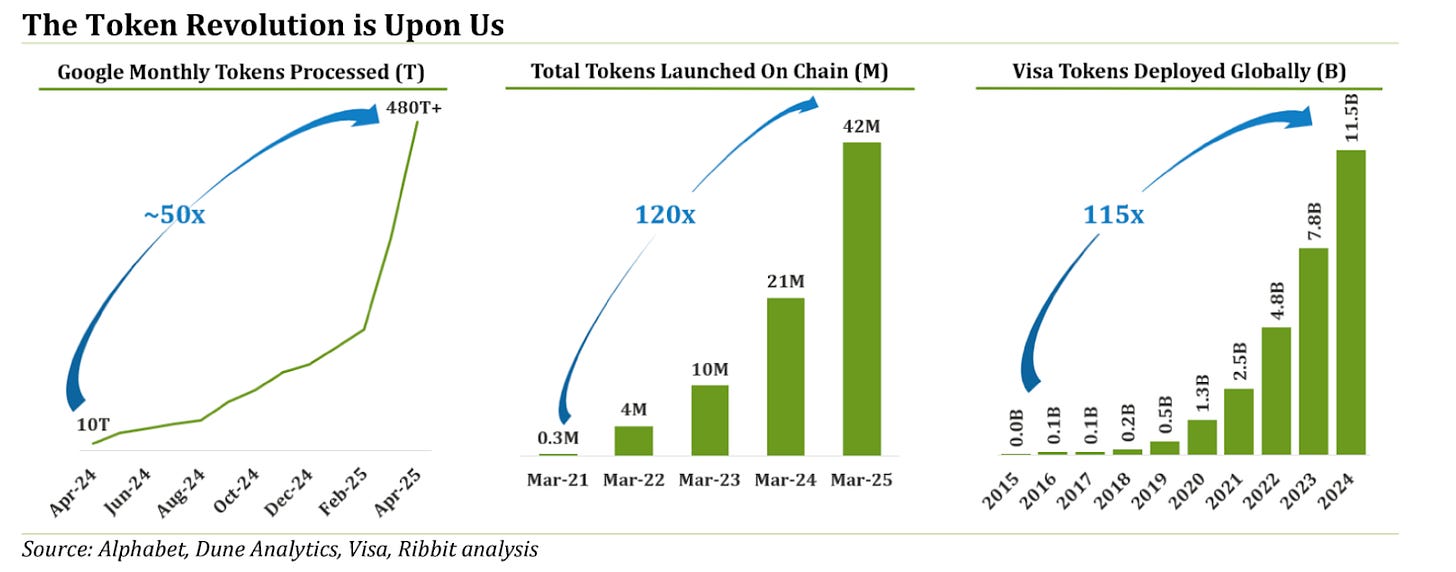

Look at what moves through the pipes now:

Bots and automation now make up nearly half of all web traffic. This was primarily driven by the rapid adoption of AI and large language models (LLMs), which have made bot creation more accessible and scalable.

API requests account for 60% of the dynamic HTTP that Cloudflare processes. In other words, machine-to-machine chatter already accounts for most of the traffic.

We designed today’s pricing models for a human-only internet. Now the traffic is machine-to-machine and bursty. Subscriptions assume habits. Spotify on the way to work, Slack during work hours. Netflix in the evening. Ads assume eyeballs - someone scrolling, clicking, considering. But machines have neither habits nor eyeballs. They have triggers and tasks.

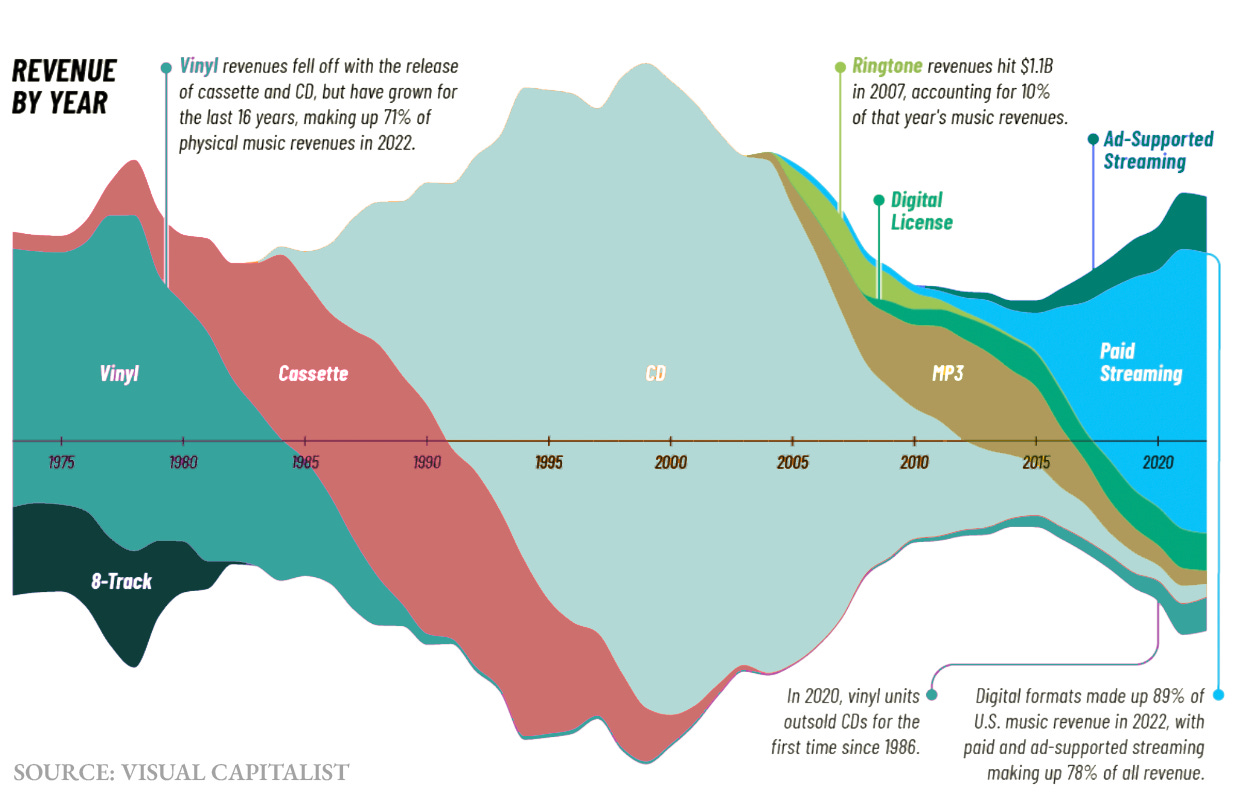

Pricing content is not just a function of market constraints but also of the underlying distribution rails. Music spent decades as albums because physical media demanded bundling. Burning one song or twelve songs on the same CD costs nearly the same. Retailers needed high margins, and shelf space was finite. In 2003, iTunes changed the unit of account to the song when the distribution medium shifted to the internet. Buy any song for $0.99 from iTunes on your PC and sync it with your iPod.

Unbundling increased discovery, but it also eroded revenues. Most fans bought the top hits, not the ten fillers, compressing per-listener revenue for many artists.

Then the rails changed again when the iPhone came out. Cheap cloud storage, 4G and global CDNs made accessing any song instant and smooth. Phones were always online, instantly tapping into an effectively infinite number of songs. Streaming rebundled everything at the access layer: $9.99/month for all music ever recorded.

Music subscriptions now make up more than 85% of music revenues. Something Taylor Swift is unhappy about: she was forced to return to Spotify.

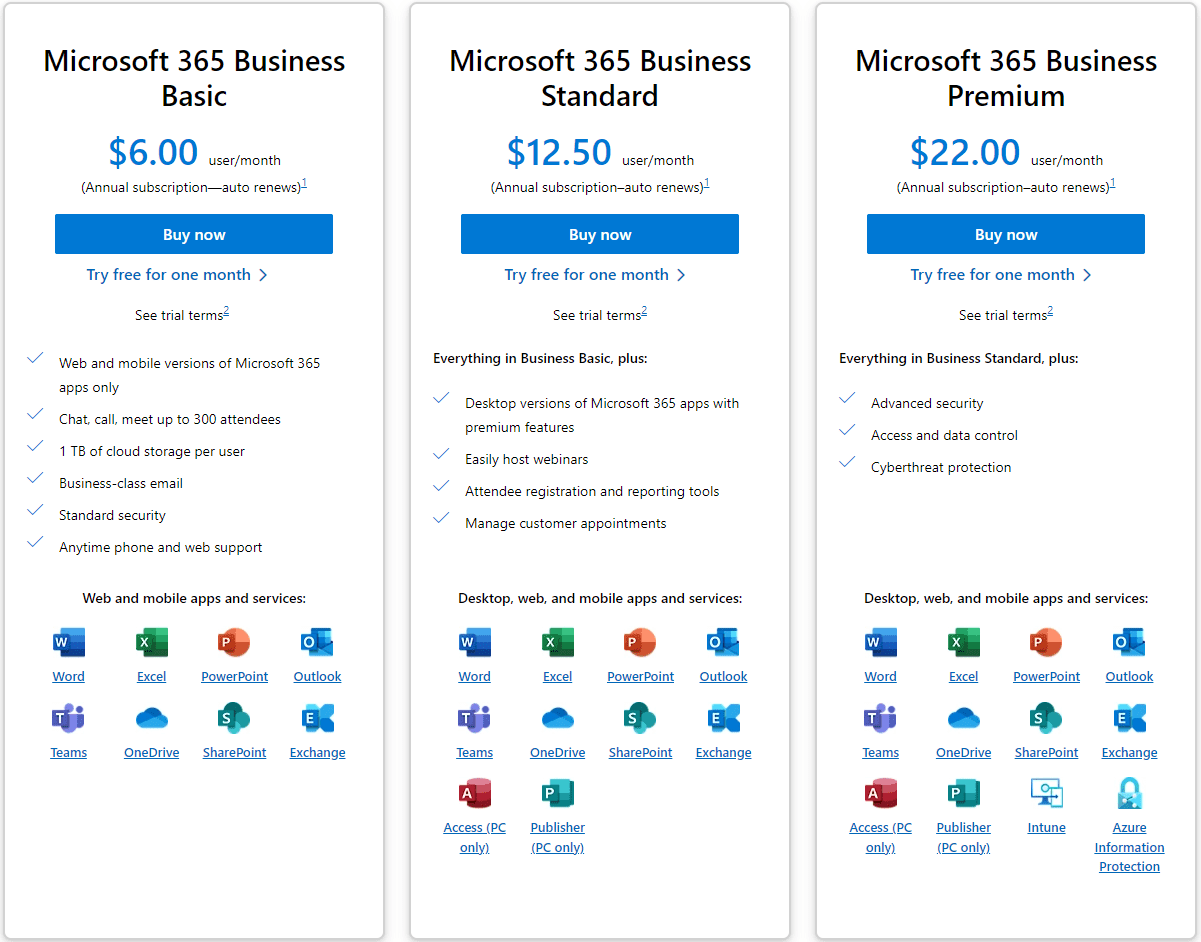

Enterprise software tracks the same logic. Because the product is digital, vendors can charge for the exact resources used. B2B SaaS vendors offer predictable access to a service on a monthly or annual basis, typically “per seat,” with tiers that restrict features, such as $50/user/month plus $0.001 per API call.

The subscription covers predictable human usage, and metering handles machine bursts.

When AWS Lambda runs your functions, you pay for exactly what you consume. B2B deals often involve bulk orders or high-value purchases, resulting in larger transaction sizes and significant recurring revenue from a smaller, concentrated base. Last year, B2B SaaS revenue reached $500 billion, which is twenty times that of the music streaming industry.

If most consumption is now machine-driven and bursty, why are we still pricing like it’s 2013? Because we designed today’s rails for humans to make occasional choices. Subscriptions became the default because one monthly decision beats a thousand micropayments.

It’s not that crypto created the underlying rails that can now support micropayments. There’s that too, but the internet itself has become such a gargantuan beast that it needs new ways to price usage.

Why Micropayments Failed

The dream of paying cents for content is as old as the web itself. Digital Equipment’s Millicent protocol promised sub-cent transactions in the 1990s. Chaum’s DigiCash ran bank pilots. Rivest’s PayWord had solved the cryptography. Every few years, someone rediscovered the same elegant idea: what if you could pay $0.002 per article, $0.01 per song, exactly what things cost?

They all died the same death: humans hate metering their own enjoyment.

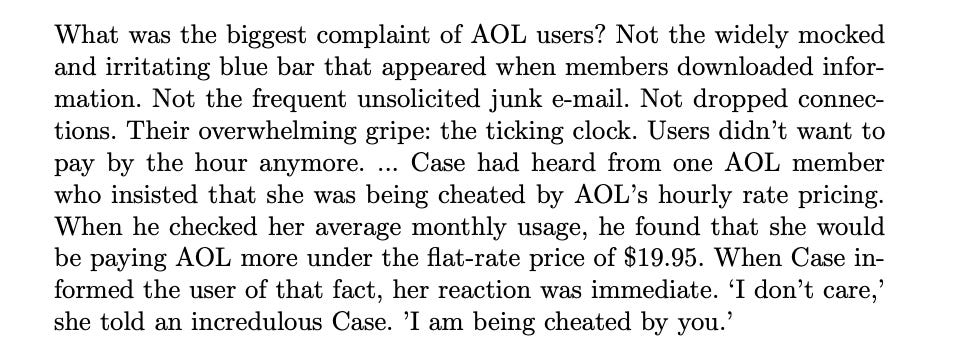

AOL learned this quite expensively in 1995.

They charged dial-up usage by the hour. For most users, this was objectively cheaper than a flat subscription. Yet customers hated it because of the mental overload. Every minute online felt like a meter running, and every click carried a tiny cost. People can’t help tallying each micro-cost as a “loss,” even if the amounts are small. Every click became a micro-decision: is this link worth $0.03?

When AOL switched to unlimited in 1996, usage tripled overnight.

People paid more to think less. “Pay exactly for what you use” sounds efficient, but for humans, it often feels like anxiety with a price tag.

Odlyzko sums this up in his 2003 paper - The Case Against Micropayments: people pay more for flat-rate plans not because they’re rational, but because they crave predictability over efficiency. We’d rather overpay $30/month for Netflix than optimise each $0.99 rental. Later experiments, such as Blendle and Google One Pass, attempted to charge $0.25 to $0.99 per article but ultimately failed. The unit economics don’t work unless a significant percentage of the reader base converts, and the UX adds a cognitive toll.

Subscription Hell

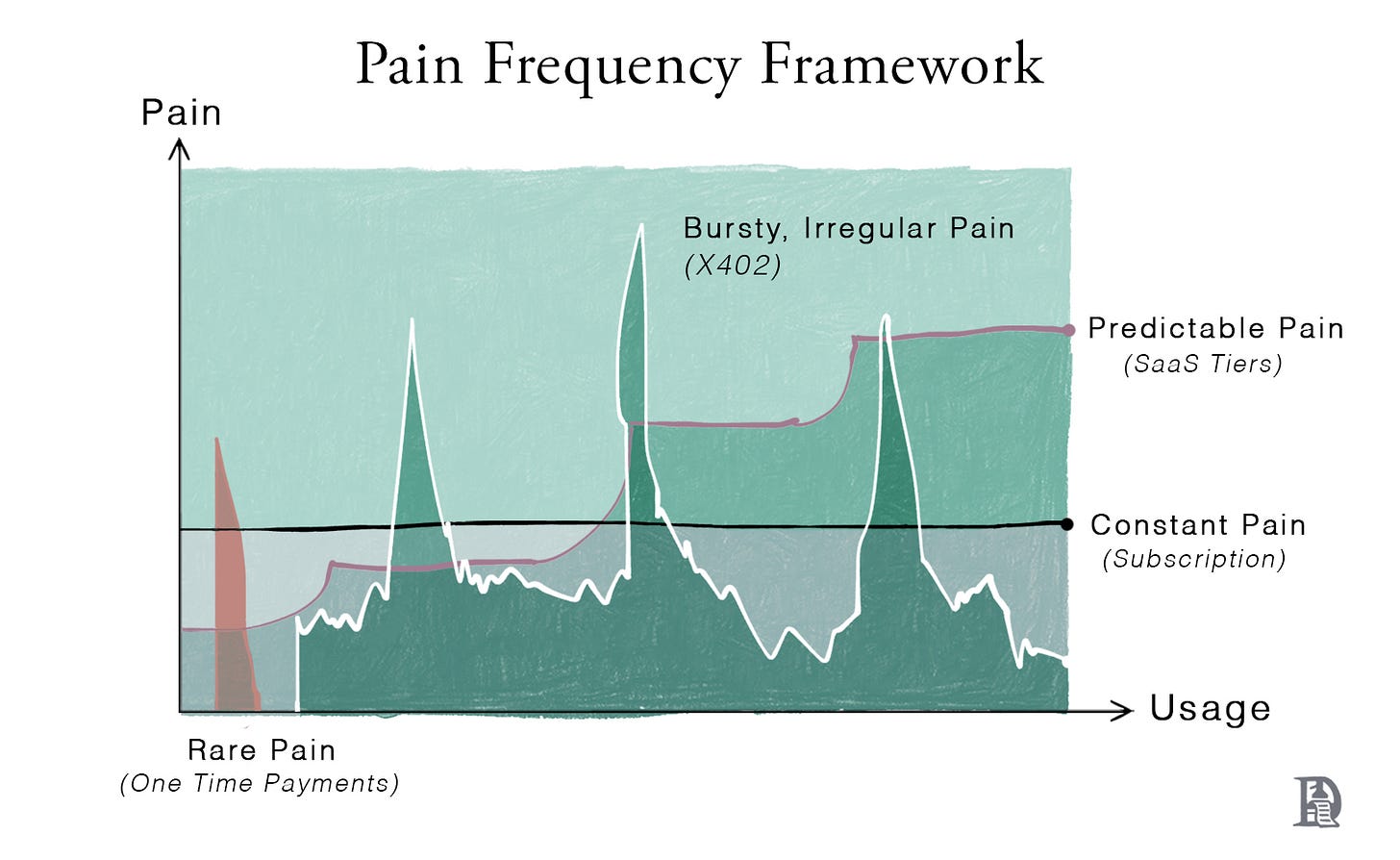

If we crave the simplicity of subscriptions, why are we complaining about subscription hell today? A simple way to reason about pricing is to ask how often you feel the pain the product removes.

Entertainment has infinite demand. The black line in the graph represents this constant pain point, the dream for both users and companies, a flat, predictable, constant pain curve. This is why Netflix went from a quirky DVD-by-mail service to membership of the elite FAANG club. It provided an endless amount of content and eliminated billing fatigue.

The simplicity of subscriptions reshaped the entire entertainment industry. As Hollywood studios watched Netflix’s stock price soar, they began yanking their catalogues back to build their own subscription empires: Disney+, HBO Max, Paramount+, Peacock, Apple TV+, Lionsgate and more.

The fragmented libraries of content forced users to buy more subscriptions. If you want to watch Anime, you need to subscribe to Crunchyroll. For Pixar movies, you need a Disney subscription. Watching content became a portfolio construction problem for users.

Pricing depended on two things: how precisely the underlying rails can meter and settle usage, and who must make the decision each time value is consumed.

One-time payments work beautifully for rare, spiky events. Buying a book. Renting a movie. Paying for a one-off consultation. The pain hits hard once, then disappears. This model works when the task is infrequent and the value is obvious. In some cases, the pain is even desirable. We romanticise trips to the theatre or a bookstore.

Measure usage precisely, and price snaps to the unit of that work. That’s why you don’t pay for half a movie. Value is ambiguous there. Figma can’t skim a fixed slice of your monthly output; creation value is hard to meter.

It’s much easier to charge a monthly fee even when it’s not the most profitable.

Compute is different: the cloud can observe every millisecond. Once AWS could meter execution at that granularity, renting whole servers stopped making sense. A server spins up only when it is needed, and you pay only when it runs. Twilio did the same for telecom: one API call, one SMS segment, one charge.

The irony is that even where we can meter perfectly, we still bill as if it’s cable TV. The usage meter runs in milliseconds, but the money flows through a monthly credit-card subscription, an invoice PDF, or a prepaid “credits” bucket. To make that work, every vendor drags you through the same gauntlet - create an account, set up OAuth/SSO for identity, issue API keys for authorisation, stash a card, set a monthly cap, and pray that you don’t get overcharged.

Some tools make you pre-load credits. Others, like Claude, throttle you to the lower model when a quota is reached.

Most SaaS lives in the green “predictable pain” band. Too frequent for one-off purchases, and too steady to justify accurate per-event metering. The playbook is bucketed tiers. You pick a plan sized to your typical month and step up when usage exceeds the limit.

Microsoft’s 1TB-per-user fence is an example of this threshold that separates light from heavy users without metering every file operation. CFO’s limit the number of users who need to access higher tiers by assigning permissions.

The Messy Middle

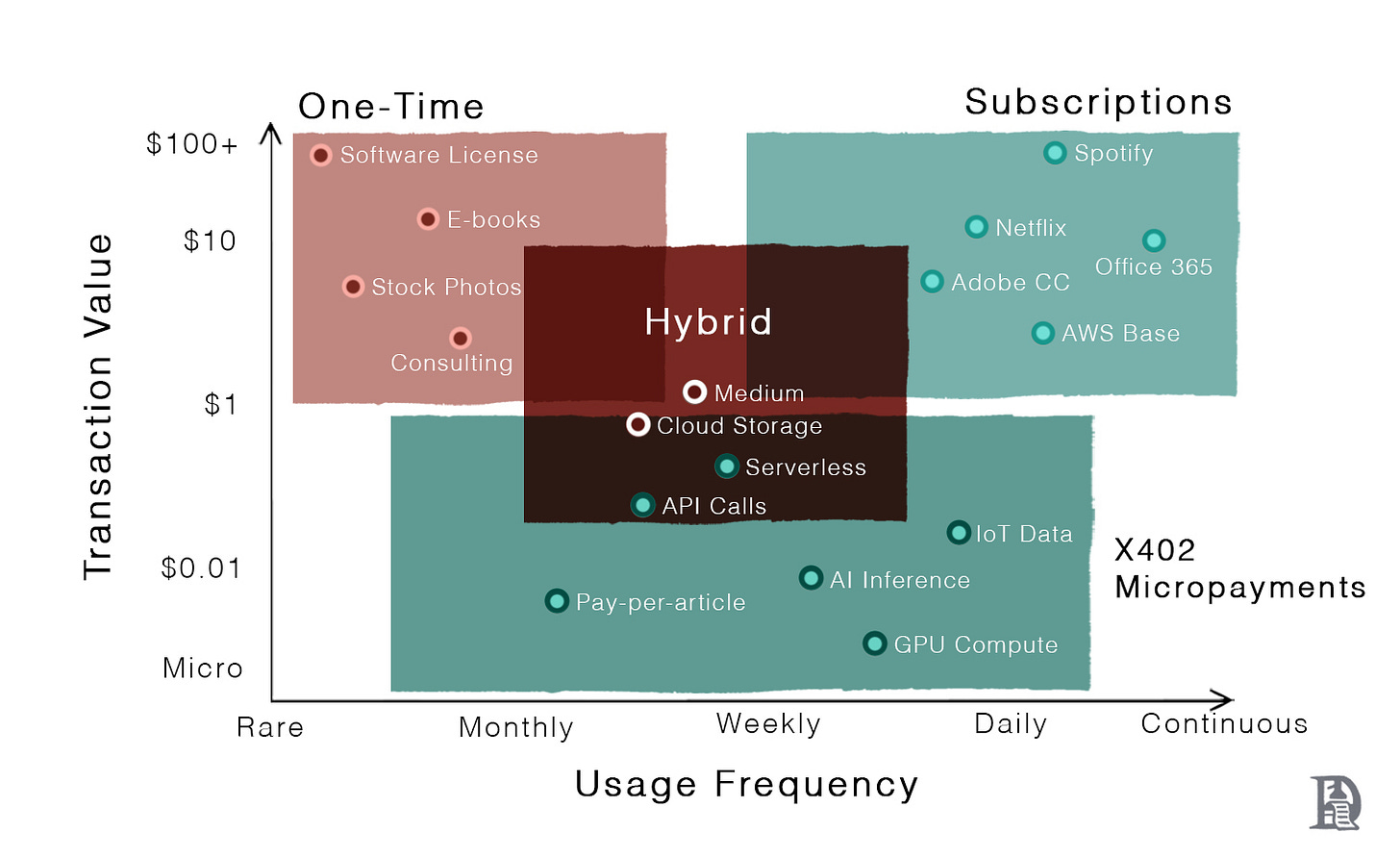

A neat way to sort pricing models is a two-axis map with usage frequency on the x-axis and usage variance on the y-axis. Variance here means burstiness - how jagged the pattern is for a single user over time. Two hours of Netflix most evenings is low variance; an AI agent that slams 800 API calls in ten seconds, then goes quiet, is high variance.

In the bottom-left corner, one-time purchases sit. When the job is rare and predictable, simple buy-and-go pricing works because you feel the cost once and move on.

The top-left is the chaotic casual web with irregular news binges, link-hopping, and low willingness to pay. Subscriptions are overkill, while per-click micropayments collapse under decision and transaction friction. Advertising became the financing layer, aggregating millions of tiny, inconsistent views. Global ad revenues crossed the $1T mark, with digital capturing 70% of spend, indicating how much of the web lives in this low-commitment corner.

The bottom right is where subscriptions make a lot of sense. Slack, Netflix, and Spotify match human routines. Most SaaS lives here, with tiers that fence off heavy users from light users. Most products offer a freemium tier to encourage users to start using their product, and then gradually shift their usage from top-left to bottom-right with daily, steady habits.

Subscriptions account for around $500B in global annual revenue.

The top-right is the modern Internet’s centre of gravity with LLM queries, agent actions, serverless bursts, API calls, cross-chain transactions, batch jobs, and IoT device chatter. Usage is both constant and jagged. Flat seat-based fees misprice this reality but lower the psychological barrier to starting to pay. Light users overpay while heavy users are subsidised, and revenue drifts away from actual consumption.

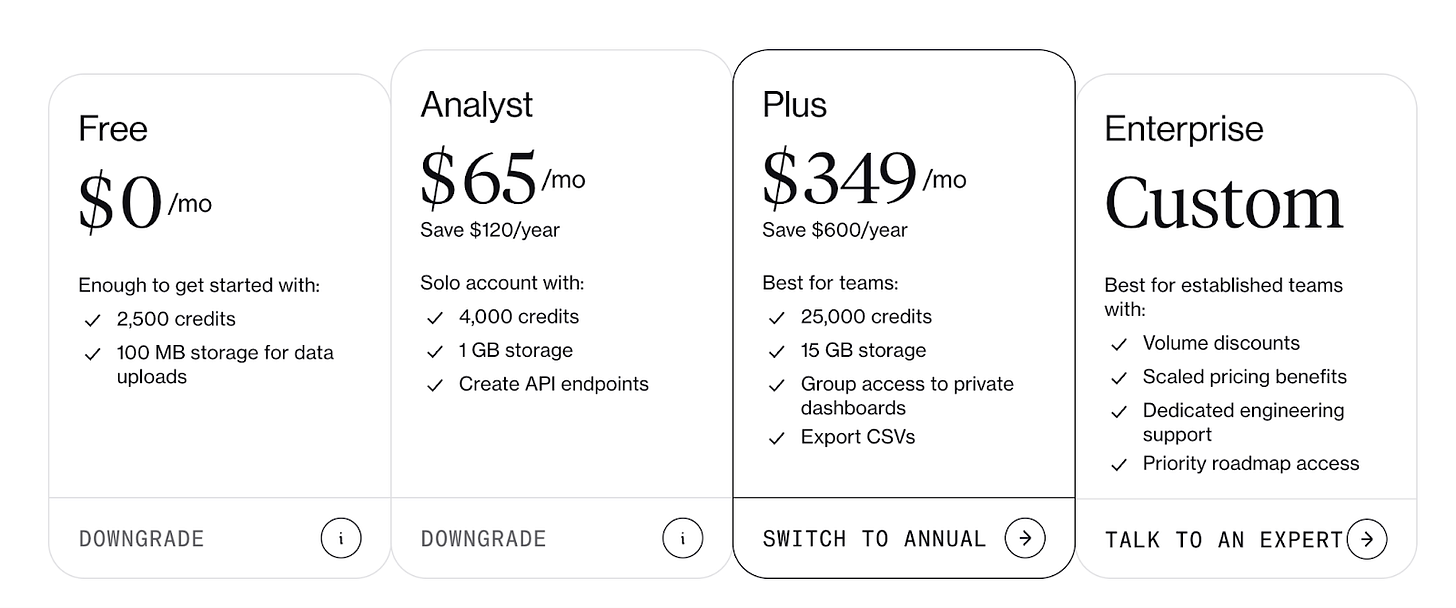

That’s why seat-led products have been creeping toward meters. Keep the base plan for collaboration and support, but charge for heavy loads. Dune, for example, offers limited credits per month. Small, simple queries are cheap, while larger queries that take longer to run cost more credits.

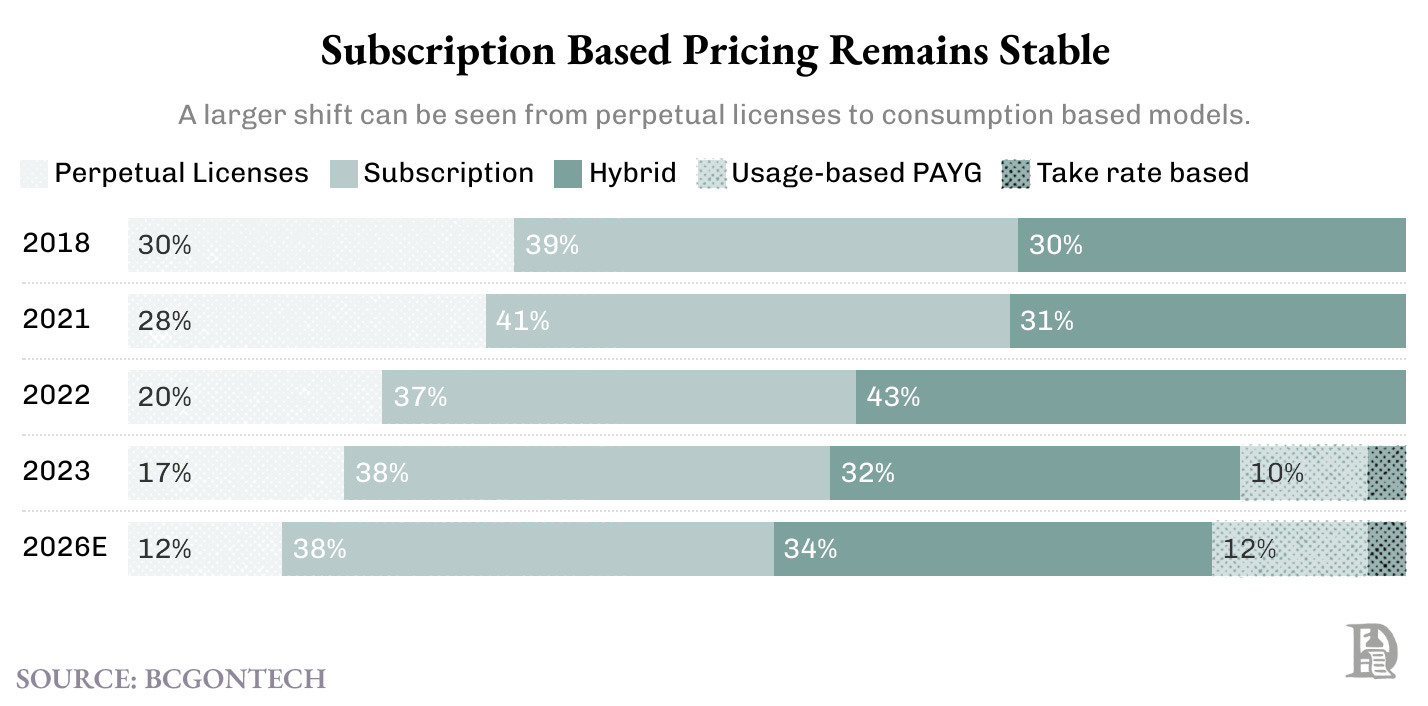

Cloud normalised per-millisecond billing for compute, data, and API platforms’ sell credits that scale with actual work. It is moving toward tying revenue to the smallest unit the network can observe. In 2018, less than 30% of software was usage-based. Today, usage-based pricing accounts for close to 50% by eating into commission-based pricing, while subscriptions remain dominant at 40%.

If spending is drifting toward consumption, the market is telling us that pricing wants to sit on the same clock as the work. Machines are rapidly becoming the largest consumers of the internet, with half of all consumers using AI-powered search. And machines are now creating content more than humans, too.

The problem is that our rails still run on yearly accounts. Once you sign up with a software provider, you get access to their dashboard with API keys, prepaid credits, and end-of-month invoices. They’re fine for humans with habits; they’re clumsy for software that bursts. In theory, you could set up a monthly recurring bill using ACH, UPI, or Venmo. These, however, would need to be batched for use as their fee structure breaks down at sub-cent, high-frequency traffic.

This is where crypto matters for internet economics. Stablecoins give you programmable, global, and granular to fractions of a cent. They settle in seconds, run 24/7, and can be held directly by agents instead of being trapped behind a bank UI. If usage is becoming event-shaped, settlement should be too, and crypto is the first rail that can realistically keep up.

What X402 Actually Is

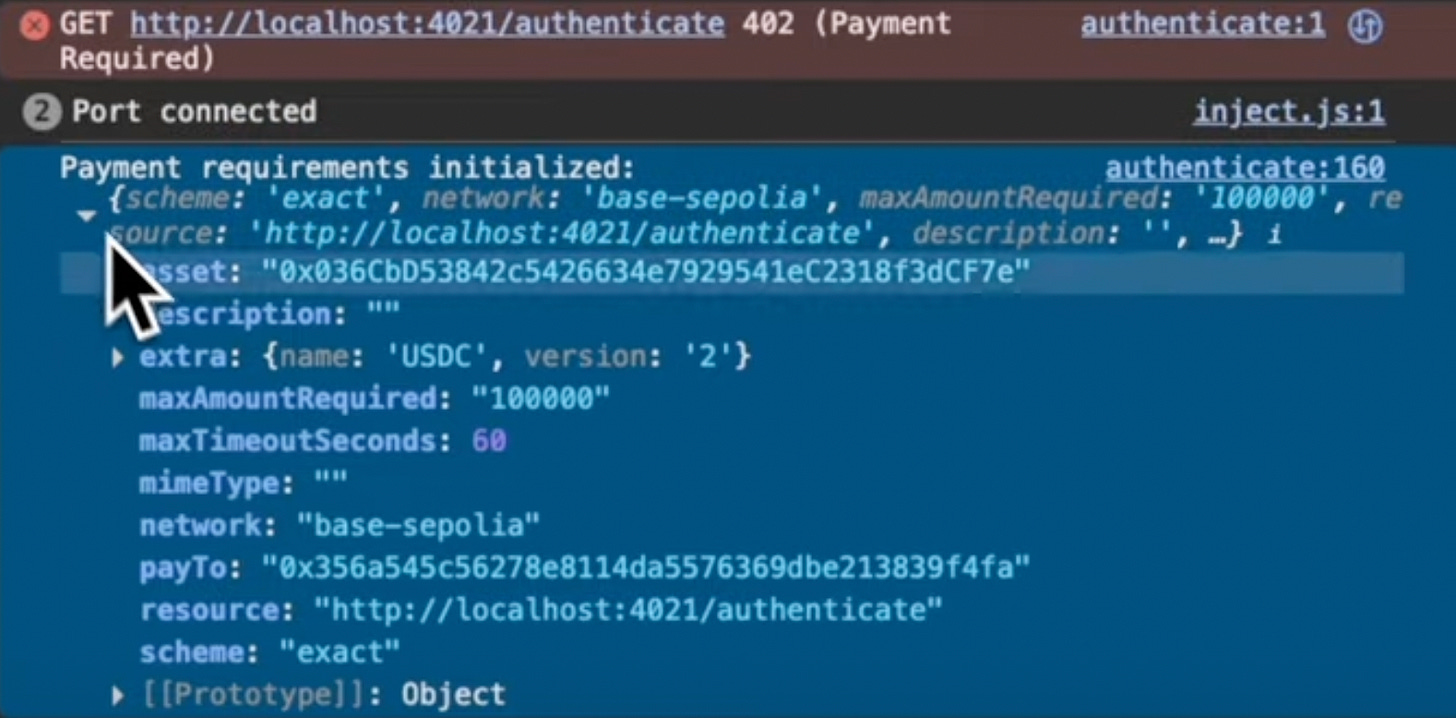

x402 is a payment standard that works with HTTP, using the decades-old 402 status code, which was reserved for micropayments.

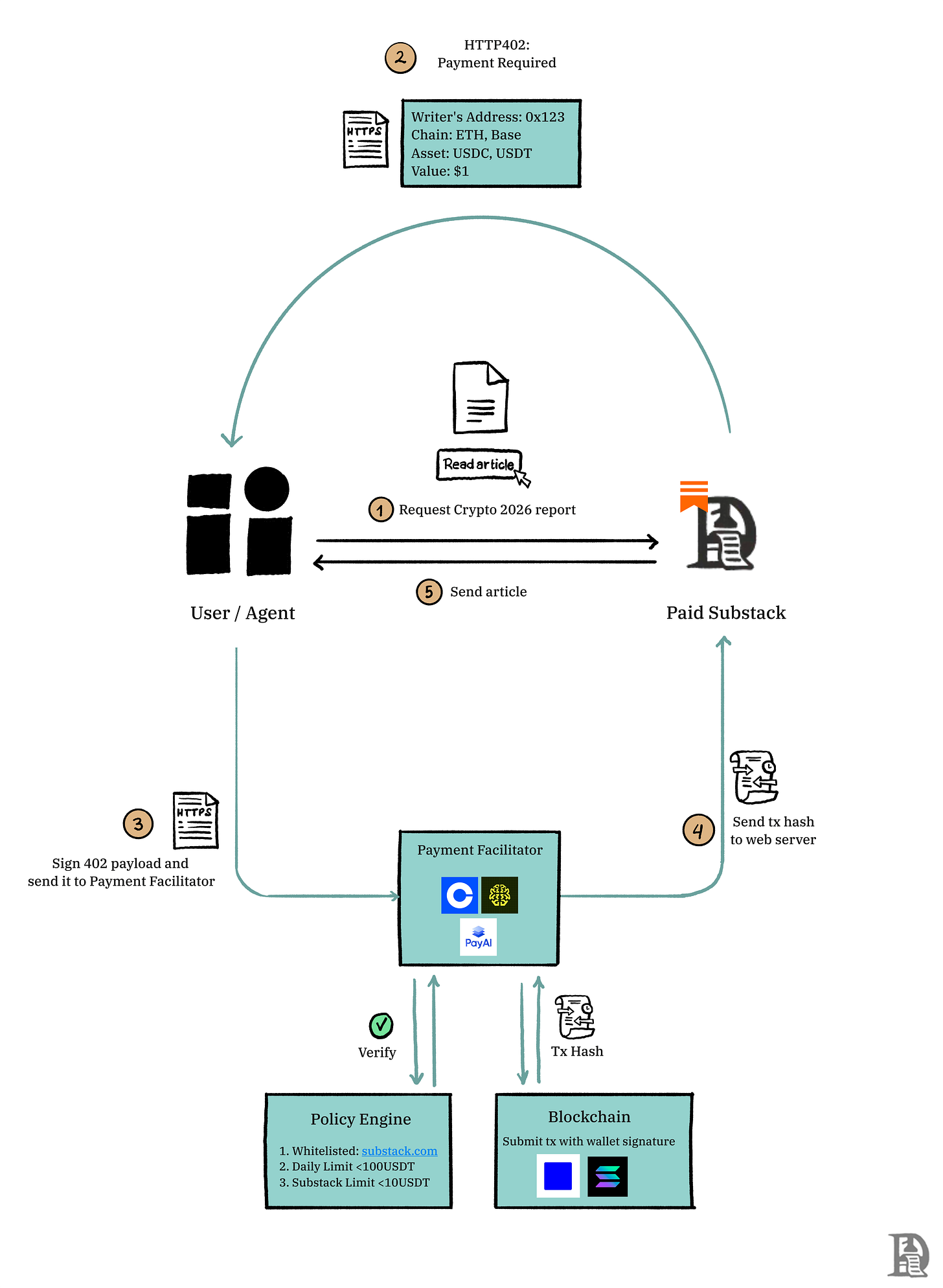

x402 is just a way for sellers to verify that a transaction has gone through. Sellers who want to accept on-chain gasless payments through x402 must plug into facilitators like Coinbase and Thirdweb.

Imagine Substack charging $0.50 for a premium post. When you hit the ‘Pay to Read’ button, Substack returns a 402 code that includes the price, accepted asset (e.g., USDC), network (e.g., Base or Solana), and policy. Something that looks like this:

Your Metamask wallet authorises $0.50 through a signed message and passes it to the facilitator. The facilitator sends the text on-chain and informs Substack to open the article.

Stablecoins make accounting easy. They settle at network speed, in tiny denominations, without opening an account with every vendor. With x402, you don’t pre-fund five credit buckets, you don’t rotate API keys across environments, and you don’t discover at 4:00 a.m. that a quota tripped and your job died. Human billing can stay where it works best on a credit card, while all the spiky, machine-to-machine paths become automatic and cheap behind the scenes.

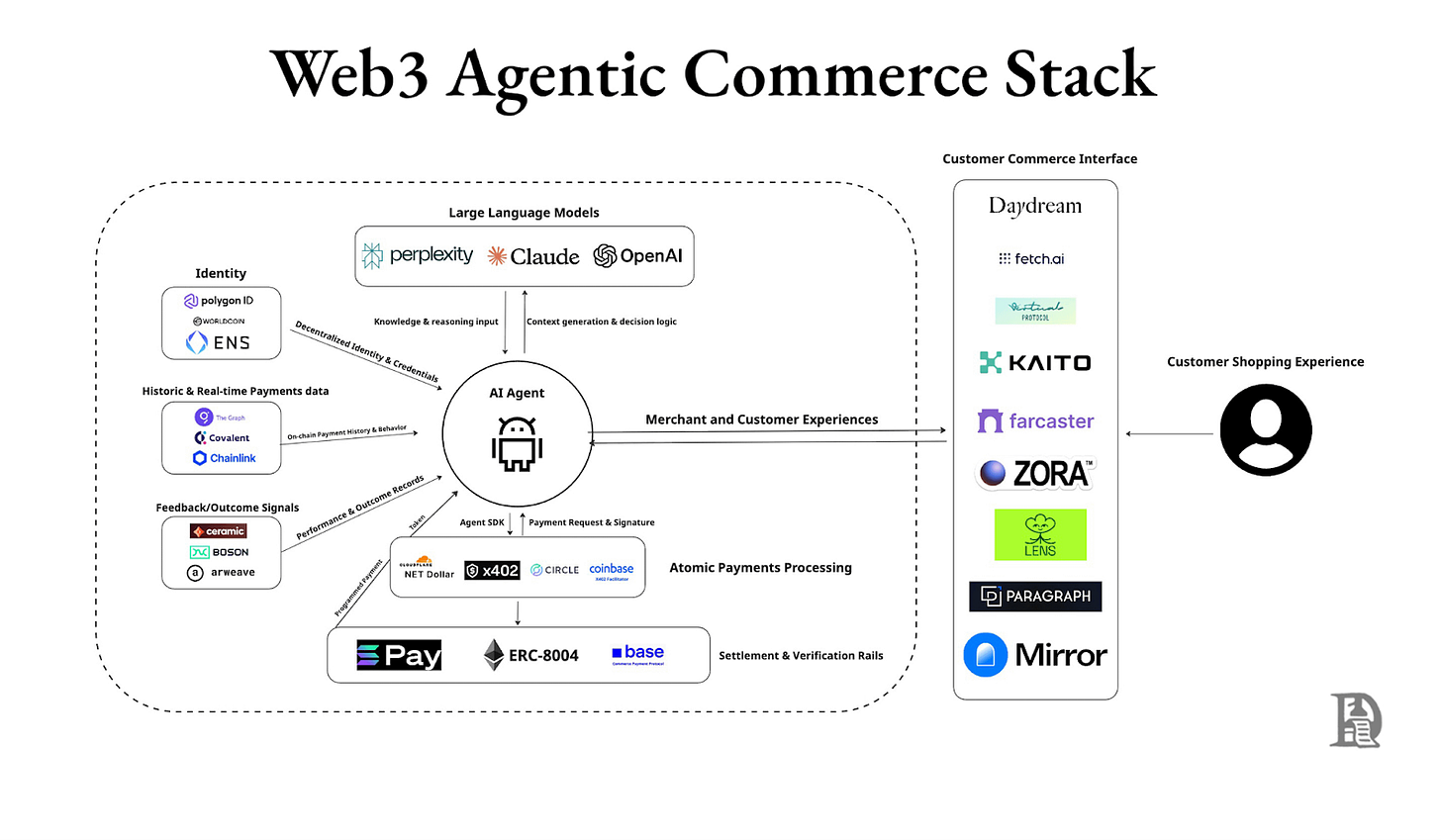

You can feel the difference in an agentic checkout. Let’s say you are experimenting with new fashion styles on Daydream, the AI fashion chatbot. Today, a shopping flow would redirect you to Amazon so that you can pay with your saved card details. In an x402 world, the agent understands context, fetches the merchant’s address and pays from your Metamask wallet without leaving the thread.

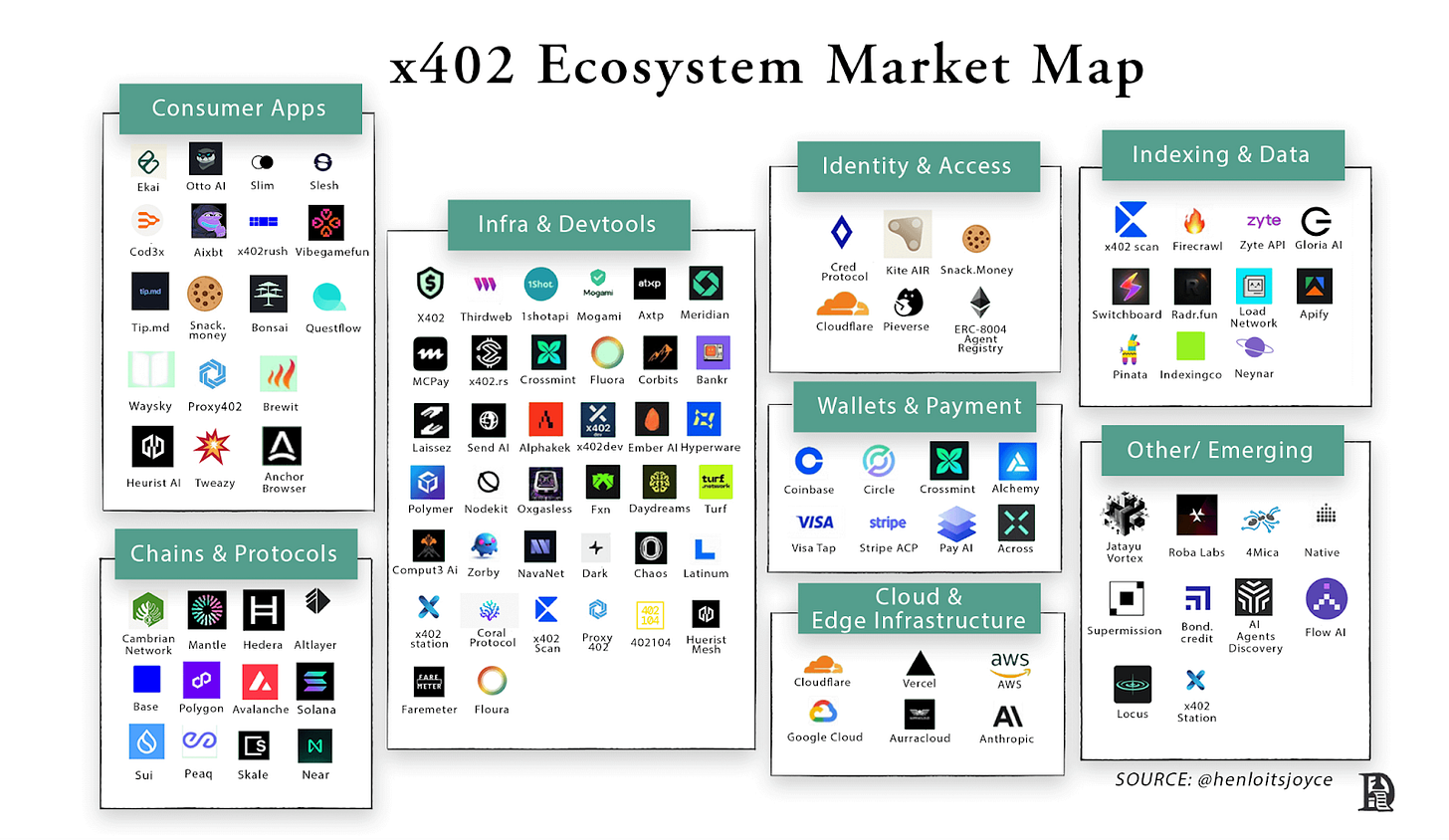

The interesting part about x402 is that, currently, it isn’t a single entity; it’s made up of the layers you’d expect to find in a real rail. Anyone building AI agents through Cloudflare’s Agent Kit can create bots that are priced per action. Payment giants like Visa and PayPal are also adding x402 as a supported rail.

QuickNode has a hands-on guide for adding an x402 paywall to any endpoint. The direction of travel is clear: unify “agentic checkout” at the SDK layer and let x402 be the way agents pay for APIs, tools, and, eventually, retail purchases.

Integrating x402

Once the web supports native payments, the obvious question is where it will take off first. The answer lies in the high-frequency usage zone, with transaction values under $1. That’s the terrain where subscriptions overcharge light users. This monthly commitment forces light users to pay the minimum sub amount to get going. x402 can settle every request at machine speed, with as low granularity as $0.01, as long as the blockchain fees remain feasible.

Two forces make this shift feel urgent. On the supply side, the “tokenisation” of work is exploding - LLM tokens, API calls, vector searches, IoT pings. Every meaningful action on the modern web already has a tiny, machine-readable unit attached to it. On the demand side, SaaS pricing leads to absurd wastage. Roughly four in ten licenses sit idle because the finance team prefers to pay per seat, as it’s easy to monitor and forecast. We’re metering the work at the technical layer but billing the humans at the seat layer.

Event-native billing with caps is a way to line those worlds up without freaking buyers out. We could have soft caps that reconcile to the best price. A news site or developer API charges per request throughout the day, then automatically refunds down to a posted daily ceiling.

If The Economist posts “$0.02/article, cap $2/day,” a curious reader can bounce through 180 links without doing mental maths.

At midnight, the protocol settles everything down to $2. This same pattern applies to developer surfaces. News agencies can charge for each LLM crawl to sustain future AI browser revenue. A search API like Algolia can charge $0.0008 per query, summing up daily usage to $3.

You can already see consumer AI edging in this direction. When you hit Claude’s message limit, it doesn’t just say “Limit hit, come back next week .” It offers two paths on the same screen: upgrade to a higher subscription, or pay per message to finish what you’re doing.

What’s missing is a programmable rail that lets agents make that second choice automatically, per request, without UI pop-ups, cards, or manual upgrades.

For most B2B tools, the practical end-state looks like a “subscription floor + x402 bursts. Teams keep a base plan tied to headcount for collaboration, support, and background usage. The occasional heavy compute (build minutes, vector searches, image generations) bills flow through x402 instead of forcing an upgrade to the next tier.

Better networks can plug in as well. Double Zero wants to sell a faster, cleaner internet over dedicated fibre. Route agent traffic through them, and you can price per gigabyte over x402 with explicit SLAs and caps. An agent that needs low latency for a trade, a render, or a model hop can temporarily step into the fast lane, pay for that specific burst, and step back out.

SaaS will accelerate towards usage-based pricing, but with guardrails:

Acquisition and activation get cheaper. You earn on the first call. Drive-by developers who never complete an OAuth or card form can still pay $0.03. Agents favour vendors who are instantly payable.

Revenue scales with real usage instead of seat inflation. That’s the cure for the 30–50% seat waste in most orgs. The heavy lifting moves to bursts with caps.

Pricing becomes a product surface. “Fast lane for $0.002 extra per request,” “batch mode at half price,” are knobs that startups can experiment with to increase revenue.

Lock-in weakens. Switching costs decrease with the ability to try vendors without integration effort and time.

A World Without Ads

Micropayments won’t wipe out advertising; they’ll shrink the terrain where ads are the only workable model. Ads will still excel in casual intent spaces. x402 prices the surfaces ads can’t reach and the occasional human might choose to pay for one great article without taking a monthly subscription.

X402 reduces the friction of paying; at a certain scale, it might tilt the future.

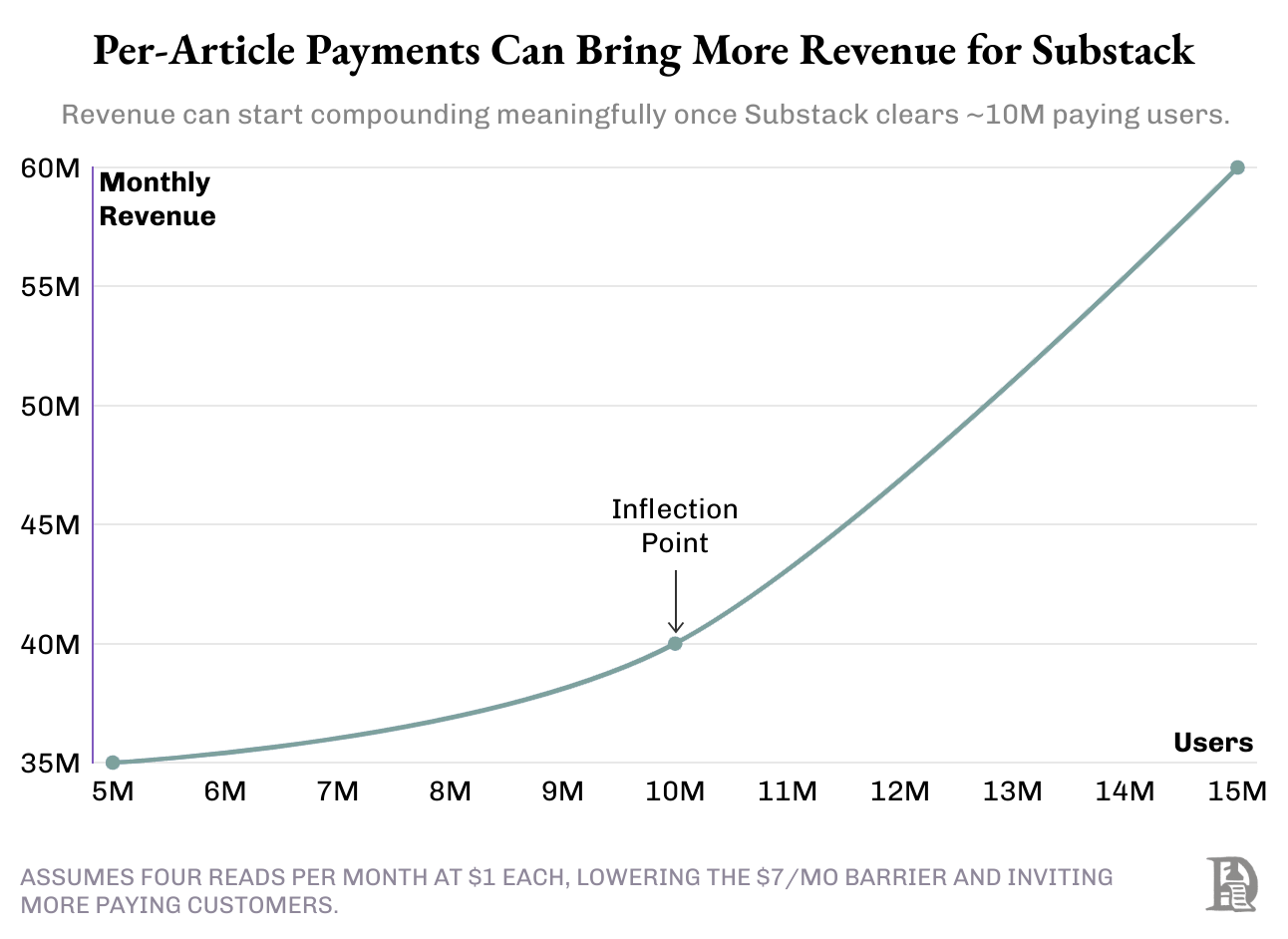

Substack has 50 million users, with a 10% conversion rate, resulting in 5 million subscribers paying around $7 per month. When the paying subscriber base doubles to 10 million, that’s probably when Substack will start making more from micropayments. Because of lower friction, more casual readers can shift towards paying for each article, accelerating the revenue curve.

The same logic applies to any seller with high-variance, low-frequency sales: when people use a product occasionally rather than habitually, paying per use feels more natural than committing to a long-term plan.

It’s a bit like my visits to the local badminton courts. I play two or three times a week, usually at different places with different friends. Most of these courts offer monthly memberships, but I’d rather not tie myself to one. I like the freedom to decide the court we go to, how often I go, and to skip a session when I’m tired.

Don’t get me wrong, I know this varies from person to person. Some prefer sticking to their nearest court, some like having a subscription that nudges them into a routine, and others might want to share one with friends.

I can’t speak for offline payments, but with x402, this kind of individuality can be reflected digitally. Users can set their own payment preferences through policies, and companies can respond with flexible pricing models that adapt to each person’s habits and choices.

Where x402 really shines is in agentic workflows. If the last decade was about turning humans into logged-in users, the next one is about turning agents into paying customers.

We’re already halfway there. AI routers like Huggingface let you choose among multiple LLMs. OpenAI’s Atlas is an AI browser that uses LLMs to run tasks for you. x402 slots into that world as the missing payment rail. It’s a way for software to settle tiny tabs with other software at the exact moment work gets done.

However, a rail alone doesn’t make a market. Web2 built an entire scaffolding around the card networks. KYC at the bank, PCI for merchants, PayPal disputes, block card for fraud, and chargebacks when things go wrong. Agentic commerce doesn’t have any of that yet. Stablecoins plus HTTP 402 give agents a way to pay, but they also rip out the built-in recourse people are used to.

When your shopping agent buys the wrong flight or your research bot blows through a data budget, how do you recover your money?

That’s what we’ll be digging into next: how developers can use x402 without worrying about future breakages.

Watching ads on Prime,

Sumanth

you mentioned : "The same logic applies to any seller with high-variance, low-frequency sales: when people use a product occasionally rather than habitually, paying per use feels more natural than committing to a long-term plan.

"

but also mentioned x402 sweet spot in top right quadrant of high frequency

isn't it contradicting?