Payment Pipelines

Embedding the future of Web3 native payments

Hey there,

Today’s issue is a sponsored newsletter written in collaboration with Paraswap. The decentralised exchange aggregator has enabled over $48 billion in volume since 2020. We use the piece today to explain the concept of a transactional aggregator, the need for embedded finance products & what the future of aggregation looks like.

Mounir - and the kind team at Six Degree Labs helped us with much of the analytics and internal expertise we needed to write for the piece.

While they had access to the piece (for informational accuracy), they did not edit the analyses we did over the past few weeks. As always, mentions of a project are not endorsements for their tokens. With all that out of the way, let’s dig in.

Tldr - for those in a hurry.

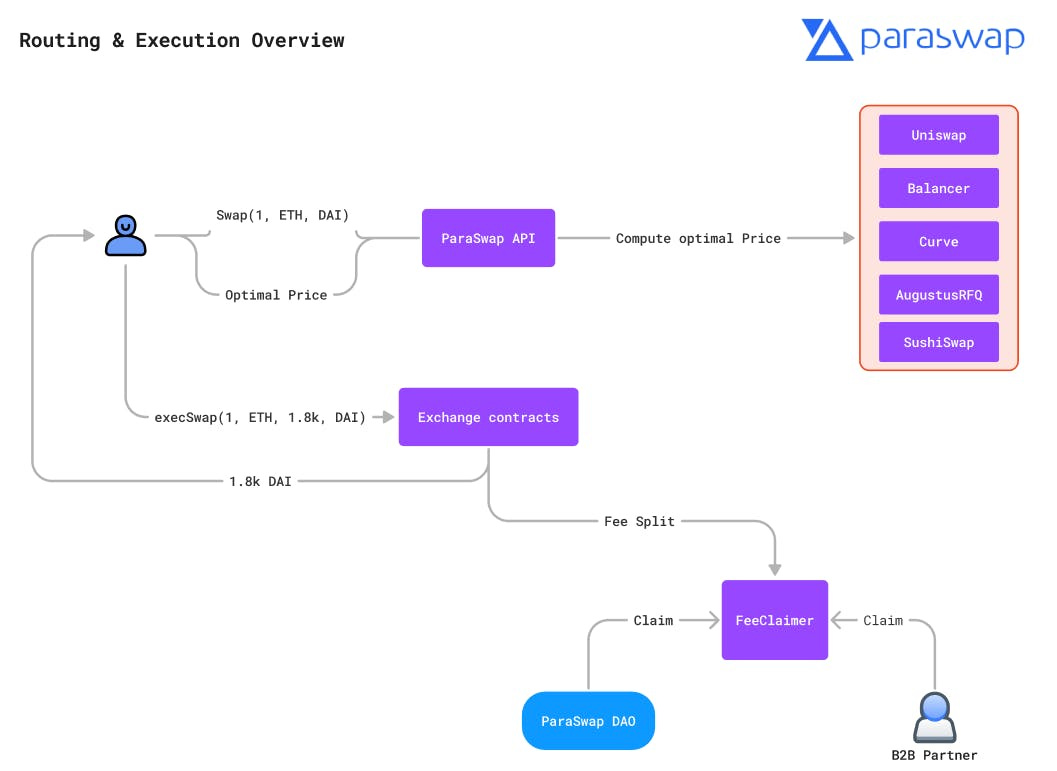

Using DeFi instead of custodial exchanges for executing trades is usually cheaper for larger order sizes. Liquidity aggregators like ParaSwap are critical for DeFi infrastructure since they simplify trading order execution.

To differentiate itself in the aggregator landscape, ParaSwap has been taking steps to grow the institutional side of the business by onboarding market-makers and other partners like wallets and lending platforms, allowing them to reach a point where 2/3rd of the volume comes from SDKs that are embedded in third-party applications.

But that’s not it! To build a sustainable moat among aggregators, ParaSwap must go through creative destruction of itself. Web2-based FinTech companies offer interesting case studies where aggregators built moats with ancillary services that enhance the value proposition of the core service.

The fee for core services such as routing and splitting trades is a race to the bottom. ParaSwap may evolve into an embedded finance platform—offering services like trading all DeFi primitives from one interface.

GM!

A year ago, in Aggregation Theory and Web3, I claimed that blockchain native projects can supersede their traditional counterparts, as the former reduce the cost of verification and trust. Few places have seen the power of this concept as well as DeFi and NFTs. The example I gave at the time was of tokens.

When you swap ETH for USDC on Uniswap, you don't worry about the 'authenticity' of the USDC you receive, as long as the right smart contracts are involved.

Part of what I missed at the time was the relevance of the goods being sold digitally. Amazon and Netflix are aggregators, but their marginal costs for adding to their inventories are not zero. Amazon incurs shipping costs on each sale. Netflix has to pay third-party studios for content or create this in-house.

In Ben Thompson's view, an aggregator (in the digital world) has a few avenues where costs creep in. Efficient aggregators manage to avoid all these. As per his post from 2017, aggregators incur zero marginal costs on the following:

The cost of goods sold (COGS), that is, the cost of producing an item or providing a service

Distribution costs, that is, the cost of getting an item to the customer (usually via retail) or facilitating the provision of a service (usually via real estate)

Transaction costs, that is, the cost of executing a transaction for a good or service, providing customer service, etc.

Blockchain-native DeFi aggregators fit this definition quite well because

You can pass on the cost of capital or goods to the user, using token incentives, as Blur and 1inch did

There are nearly no costs incurred by aggregators for passing on the final good (an NFT or token) to the user

The user bears the gas costs and it generally trend to zero with the arrival of L2s

One can always debate whether token economic incentives are a cost to the protocol. Take the case of Uniswap – was the airdrop they offered a cost to the protocol or a mechanism to generate $6 billion in collective value for all stakeholders?

That debate does not fit here, so we will skip it for now. But I wanted to refresh your memory on the matter for a different reason: to introduce the concept of a transactional aggregator.

Building further on Ben Thompson's work (and my piece from the last year), a transactional aggregator is one that holds zero risk for the liquidity it offers by sourcing it from a third party with no fees for doing so. Unlike Amazon or Netflix, transactional aggregators can scale infinitely by tapping into liquidity from external platforms. No marginal cost is incurred (by the platform) in supporting larger orders.

Note: I wondered for a while if Stripe and Plaid are transactional aggregators. In my understanding, they are data aggregators tracking the flow of capital via third-party payment networks (Visa, ACH, SWIFT). The settlement of payments itself does not happen via Stripe or Plaid.

They have the benefit of scale from focusing on a traditional asset like fiat, but they are still dependent on a third-party network's willingness to work with them. In the case of open-source, networked-capital platforms (like Uniswap), there is rarely a choice of blocking out a third-party aggregator plugging into it.

We may need a conventional example to explain why this matters. Let's take Charles Schwab and Robinhood – both instances of zero-fee stock trading platforms.

They hold large pools of user capital that are often isolated. If a user had to do a block transaction of a million shares of Apple – like Steve Jobs did here in 1997 – they would go through an investment banker or a specialised service handling such transactions. You have a central party that takes these orders, assumes the risks on their own books, and sells them over time.

In the case of Web3 native pools of capital, like the liquidity pools on Uniswap, any third party can build an application that taps into that pool of money.

A developer can build an app that taps into multiple pools of liquidity to absorb an order without ever interfacing with the developers of stand-alone, external AMMs like Uniswap or Sushiswap. A variation of this was evident in the early days of Blur and Gem.xyz, too. Networked pools of capital, running on smart contracts enabled by public, permissionless ledgers can rarely dictate who interacts with them.

(I understand how little sense the last sentence would make to someone outside this industry. Apologies to them.)

The lack of liquidity for the tail end of assets was beginning to creep up on spot exchanges like Uniswap, right as DeFi summer took off. Given how these systems work, users can trade $10k of smaller altcoin within a 1% price difference. But what if they wanted to sell $100k worth?

You have a problem. This is where a transactional aggregator like ParaSwap comes in. However, before I discuss how it all came together and what its future looks like, it serves to understand what ParaSwap does today.

New Engines Under The Hood

Here is a quick breakdown of some financial jargon before we go further.

Liquidity is the amount of capital (dollars or ETH) available on an exchange against which you can trade. If you have a token priced at $10, with a liquidity of $1, what you may really have is ~$1.5 or $2 and not $10 because you won't be able to sell all those tokens at $10. Where did all your money go?

This is where you meet your friend 'slippage' for the first time in the markets. If nobody is willing to buy your token at $10, you will now have your order to sell settled at a new, lower price.

For illiquid assets, this could be 10%–20% lower, depending on how many people wish to buy the asset. Last year, FTX imploded partly because the risk assessment team there seemingly didn't know how these concepts work.

That difference - between the price you wanted and what you got, can be defined as slippage.

Keep these terms in mind as we navigate the following few examples. The image below shows what happens when a user tries to sell $1.75 million worth of ETH for DAI on ParaSwap.

In the above hypothetical example, instead of sending the token down to a single exchange where there may be only $500k waiting to buy the asset without slippage, a transactional aggregator could break down that order and send it to multiple exchanges. You may still not get the $1.75 million you hoped for, but you could get close to it depending on the number of exchanges plugged into the aggregator. The image below examines how an order of $1 million worth of ETH would be split up to reduce slippage.

You may wonder why users wouldn't go to Binance to sell their tokens. The fact is, for the vast majority of the tail end of assets – in the absence of multiple market-makers – liquidity on CEXs and DEXs is very low. Even selling $100k of tokens can collapse price substantially for tokens with smaller market-caps. You may be able to sell $100k of ETH without price slippage, but the moment it scales to $1 million, you are losing money to slippage.

That assumes you are comfortable parking a million dollars in an exchange (like Binance) after last year's FTX fiasco.

An alternative for users is using decentralised exchanges like Uniswap, Sushiswap, and Balancer. But that assumes the user will bother looking at prices at multiple exchanges, then click the sell button within milliseconds of selling on each exchange and somehow calculate the right amount to be sold on individual exchanges to receive the maximum hypothetical returns.

In the example above, a player like ParaSwap routes the order across multiple decentralised exchanges, assuming the price should not fall below 1% while the transaction is being conducted. The two charts show how much of the asset can be sold before the price moves. This is where you can see a transactional aggregator at play.

The three exchanges (Uniswap, SushiSwap, and Balancer) can put the capital in their liquidity pools to use through large orders coming from ParaSwap.

ParaSwap does not incur marginal costs from sourcing liquidity or routing trades across platforms.

The user minimises costs incurred in transacting across multiple exchanges while avoiding the counterparty risk that comes with a centralised alternative like Binance.

A component drives marginal costs even lower in this equation: the emergence of L2s. In particular, they reduce the on-chain costs to a point where centralised exchanges begin looking inferior. While centralised exchanges charge a percentage fee on every trade, gas fees remain consistent regardless of the trade size.

That is, the marginal cost of trading on a DEX does not necessarily scale with the size of the order involved, presuming there is sufficient liquidity. This is the one part of crypto-economics that is being massively discounted.

When the marginal cost of each transaction trends to nothing, we'll see a whole new class of applications. For now, we are trying to merely catch up with certain centralised businesses that are crucial to the industry. We did the math on how it works for centralised exchanges.

From a purely economic perspective, trade size and gas fees remain the two major factors in deciding whether to use a centralised exchange or DEXs on either base layers or L2s like Arbitrum.

The following table shows how beneficial it is to trade on a DEX on Arbitrum compared to Binance.

The sensitivity analysis uses fees for a swap on Arbitrum and compares it with fees on Binance (0.1% of the trade size). Green indicates that it is cheaper (by the amount) to trade on a DEX on Arbitrum versus Binance, and red indicates otherwise. For example, if an Arbitrum DEX is used to swap $20k worth of tokens when the fee is $2, it is $18 cheaper than the fee on Binance (the fee on Binance will be $20,000*0.1% = $20).

An added advantage of DEXs is they are non-custodial: Users are always in control of their assets. We have come to value this after what has been going on with centralised exchanges over the past year.

After EIP-4844 goes live, L2s will incur lower costs while posting data on the L1, increasing the L2 throughput by at least an order of magnitude. EIP-4844 will implement a transaction type to hold a' blob' data space. Note that since moving to proof of stake, Ethereum has separate consensus and execution layers. The blob space only persists on consensus clients. ( We are writing about all the EIPs you need to be aware of in the next newsletter).

Data inside the blob is not visible to the Ethereum virtual machine (EVM) and incurs only storage costs. Unlike data in regular blocks, this data is only available for a certain period. The absence of EVM dependency and execution costs yields significantly cheaper transactions (1%–10% of fees before 4844 goes live).

For now, there is evidence that the DEX volume has shifted from L1 to some L2s. For example, the share of Arbitrum in the DEX volume has increased from ~1% to ~14% in one year versus a drop from ~70% to ~57% for Ethereum.

How It Began

Mounir started working on ParaSwap by himself. He had been building on verticals in transportation and data since at least 2007. So this was not his first foray into entrepreneurship. In 2017, he sought to create an alternative to the decentralised exchanges of the time.

His focus was on improving UX. But during those early days, users needed deeper order books, not an easier interface. And protocols like Kyber and 0x were better positioned for this.

Mounir was working alone with a single external freelancer. He realised that instead of competing against every DEX that was seeing liquidity at the time, he could build a single aggregator that sent the DEXs all orders. Most of the aggregators that existed at the time were more like portfolio managers.

A single interface showed you the value of your assets and the price at which they could be sold at multiple exchanges. However, none of these routed orders the way an aggregator in DeFi does today.

ParaSwap took a few months to build its product, and the company launched in September 2019. At this point, the startup was funded by Mounir's freelance income as the company was not generating enough revenue to sustain its expenses. One of the smart things the firm did during those early days was embedding deep in communities to acquire users. Mounir was a contributor in a chat with some 3000 members at the time.

It is where he found his initial users. But there was no explosive growth just yet. What he had very a subset of users that loved his product and a vast majority that did not care.

By March 2020, DeFi summer was about to kick off. Still, the crash in the market meant no investors were willing to write a cheque. With Compound launching its token in July, the sentiment in the market changed. ParaSwap received commitments worth three times as much as they were in the market to raise.

The firm went from just Mounir and a freelancer to having over 15 people in months. I think there's a lesson for founders raising in the current bear market. Sometimes, most of achieving 'success' in venture land is surviving long enough for markets to turn. We also saw this variation with Sky Mavis, the studio behind Axie Infinity.

Part of what helped Mounir navigate those months (in 2019) was his continued tinkering until he found PMF. He survived long enough for sentiments on the product to change. If a founder moves on to something else (like AI), the person would not have the context to build on when sentiments eventually change. ParaSwap evolved from the hundreds of conversations with fellow founders and users that helped build context about market needs.

The current ParaSwap model has a single function: provide large volume exchange transfers and the best pricing possible. ParaSwap has a pricing aggregator that sources prices from DEXs and off-chain pricing (RFQ, or request for quotes, from the likes of 0x). Although this appears simple, it's not always the case. Constant pool imbalances in DeFi mean there is always room for finding better rates for users.

For example, say a user wants to swap USDC for ETH. The straight path from USDC to ETH may not yield the best rate. USDC to sUSD to ETH is likely more optimal when the user wishes to perform the swap. So ParaSwap continuously checks for the best possible route, which may not always be the shortest.

Now, say the best route can only accommodate part of the order, necessitating the execution of the rest through the next best paths. Sometimes pathfinding requires splitting the order into multiple chunks. Once the best possible rate is displayed and the user agrees, the swapper contract executes the swap.

But how does any of this even make money? Structurally, ParaSwap's customers want to move large batches of one asset to another. These can either be institutions or third-party DeFi applications like wallets. One may not think of these as such, but Robinhood and PayPal, for instance, are one of the largest custodians of digital assets.

ParaSwap drives growth by embedding itself as a thin layer among applications that help users interface with digital assets. Say a wallet like Argent wishes to enable someone to swap $100K worth of tokens. Argent itself does not want to bother taking the risks of facilitating a swap. They embed a player like ParaSwap to fetch the best prices and enable an exchange for the user.

On its own, these standalone integrations may not mean much. But with the growth of the ecosystem of applications using ParaSwap as a thin layer for facilitating swaps, the volume that goes through the product also grows. One place where you may have unknowingly already used ParaSwap is Aave. When you take a loan and swap the asset on Aave, the product uses ParaSwap to facilitate that transaction.

But what portion of ParaSwap's volume comes from businesses? As it stands, 2/3 of the volume on ParaSwap is from external sources. That is, the orders come from SDKs that are embedded in third-party applications. Keep this stat in mind, as we'll be revisiting it shortly.

Here is a summary of the economics at play:

When wallets like MetaMask and Argent use ParaSwap for their built-in swaps, they charge a fee to the user. Although these wallets get to use ParaSwap's services for free, ParaSwap takes 15% of the fee these wallets charge their users. ParaSwap has over $2M in annualised fee revenue in 2023 compared to 1inch's $2.24M and CoW Protocol's $5.56M.

When a user initiates a swap, the expected amount of the asset is displayed to the user. If more than the expected amount comes back to the user due to more inefficiencies (created in the time between the swap being initiated and executed), ParaSwap keeps half of the excess amount.

For example, if a user goes to swap $100 in USDC to USDT and sees a quote that said they would receive $99.75, but the smart contract returns $99.90, ParaSwap would keep the extra $0.15.

Such pricing inefficiencies are rare for smaller transactions but frequently occur when swaps are conducted for large sums.

DeFi aggregators are evolving from competing to having a clear pecking order. 1inch, for instance, has maintained a clear lead, controlling 60% of the market for multiple months. Given how power laws work, aggregators are forced to expand towards newer markets. In our view, the market has evolved over the past year in response to FTX going down.

If regulatory scrutiny continues focusing on centralised, spot exchanges like Binance, the volume will trend towards their decentralised peers like Uniswap. That window of opportunity for DeFi may emerge in the coming months.

For ParaSwap to maintain relevance and evolve to absolute dominance, it must consider a different way of approaching users altogether. Many of these approaches are replicable by 1inch, but based on our observations, aggregators do not differentiate themselves with infrastructure alone. They also offer services such as analytics or user behaviour data.

Web2 applications stick with an aggregator due to all the additional offerings it can offer. We have seen a variation of this with Li.Fi aggregating bridges. Teams embedding their offerings are not coming for the bridges alone but for the value-added services they offer.

Looking through this lens, we believe that ParaSwap will evolve from being an aggregator (and thus competing with 1inch) to focusing on embedded models of driving volume. It may seem far-fetched, but remember, 2/3rds of ParaSwap's volume comes from external sources today. Currently, 57 businesses rely on ParaSwap to enable users to transact.

Aave's integration of ParaSwap shows what true composability using SDKs in DeFi looks like. It takes collateral from a user's debt position, converts it, and repays the loan, all without the user ever having to leave the app. This is what the future of ParaSwap looks like.

Embedding the Future

To understand why embedded forms of finance will be required going forward, we need to go back to the early 2000s, when eBay was taking off. At the time, to make payments meant, you placed an order online, sent a physical cheque to the seller, or transacted manually through a bank.

This meant that confirming an order might take weeks, the cheque might be bounced, or users would lose interest because physically going to the bank might be inconvenient. PayPal solved this by offering a simple payments page that could be embedded directly on eBay. All of a sudden, users were not going elsewhere mid-transaction.

This may be the norm in the age of Apple Pay, but consider how Web3 interactions work today for the tail end of assets. We presume that users will go to Uniswap, convert ETH or stablecoins to the required token, return to the platform, and continue their transactions.

I believe wallets and service providers will begin embedding exchanges in their apps directly. On its own, this is not a big deal. You can embed Uniswap or a third-party decentralised exchange with relative ease. But a single SDK that looks at all the permutations and combinations an asset can flow to acquire the best price? That's where ParaSwap will kick in.

This story has played out in finance earlier. A relevant example is that of BharatPe.

November 8, 2016, was pivotal for India's digital payments industry. The Prime Minister announced demonetisation - a point in time when the currency people held at home (as notes) was no longer valid. While local businesses like Kirana stores (the mom-and-pop stores in India) that dealt in cash were reeling from the shock, digital payment companies rejoiced.

In 2016, India had just over 12.5 million Kirana stores. Due to the shock to the cash system, moving to digital payments was the way forward. Wallets like Paytm and PhonePe began acquiring customers in the region, but UPI - the payment system used, was not widely adopted yet.. Two other problems hindered the widespread adoption of digital payments:

The biggest was every payment processor, or wallet operator worked in silos. That is, everyone had a unique QR code. This meant that the shop owners would have to install multiple QR codes if they were to accept money from numerous wallet providers.

While the transaction was free for users, every payment processor charged at least a 1.5% fee to the merchant. This meant the merchants' bottom line would get further hit in profit-starved businesses. For example, for an Rs. 1,000 (~$12) purchase where the typical margin was Rs. 100–150 (~$1.2–$1.82), the shopkeeper would have to pay Rs. 15 (~$0.18) as commission to the payment gateway.

Enter BharatPe. Started in Mach 2018, BharatPe utilised one of the most critical features of the UPI stack – interoperability. Merchants would now only have to use one QR code regardless of which payment gateway or processor the user was using. BharatPe installed these QR codes nationwide (with over 5 million merchants onboarded).

This took care of the first problem mentioned above. Having worked at Grofers (an online grocery delivery startup in India) as the CFO, Ashneer Grover realised charging commissions to merchants operating on razor-thin margins was not the way to scale the business.

Although merchants were not happy with paying commissions for payments, they were more than happy to pay interest on short-term loans they would require for their businesses now and then. Despite micro, small, and medium enterprises being vital elements of the Indian economy, private banks were reluctant to extend loans to them due to the lack of collateral or documents.

BharatPe used data from its QR codes for risk management to start offering loans to merchants without requiring collateral. This took care of the second problem mentioned and created a source of revenue despite offering critical services for free.

Now we won't go into more examples of fintech behemoths forming out of embedded finance being a thing, but we see a variation of this happening live with ParaSwap and NFT markets today. For instance, a user wishes to sell their NFT for DAI, and a different user wishes to pay with ETH.

ParaSwap makes that exchange happen with one click, which means, in the future, there will be no ETH-, SOL-, or Matic-based NFT markets. Products like games, fintech apps, or DeFi platforms can embed a single SDK from ParaSwap and enable transactions in any token. The challenge here for ParaSwap would be to expand to bridging assets – a feature they do not currently offer.

Users do not flock to DeFi instead of exchanges because of the former's lack of options. Today, you cannot do margin, options, spot trading, and lending through a single interface in DeFi. Even when the apps exist, there are no market makers facilitating volumes. One avenue for ParaSwap to expand into would be to be the financial backbone routing liquidity for all kinds of primitives in crypto.

Today, they focus on spot assets. But what’s stopping them from making debt positions tradable?

The challenge most stand-alone options or insurance products face today is volume. Around 30,000 wallets interact with ParaSwap daily. Offering an interface where users can purchase these instruments through ParaSwap is the lowest-hanging fruit. And it is likely that its peers, such as 0x Protocol and 1inch, follow it when that does happen.

But how do you build moats in such a system? Regulatory provisions in traditional payment rails like ACH or Visa make the entry barrier high. In open-source monetary networks, anybody can emerge and compete. As stated earlier, the way forward is for ParaSwap to front-run new product categories. What would those categories be? The image below offers some clues.

The range of assets supported by DeFi has barely scratched the service. The image above is from Tioga’s Substack.

One of the directional bets ParaSwap could take at this point is to focus on institutional clients. An RFQ-based product built by ParaSwap allows exceptionally large orders ($10 million+) between verified, compliant counterparties to trade with one another. In such a system, ParaSwap does not have to worry about providing liquidity for trades but offers the interface for routing orders.

In such an instance, the moat will come from the number of large institutions that follow on to such a product. We have verified that the team onboards several market-makers to focus on such a product. Liquidity begets liquidity. The more the number of institutions onboarded to such a system, the higher the probability of other institutions joining.

Another direction is to look at niche assets that have not yet found a large enough market. One of them is RWA assets. Aave and MakerDAO realised the limits of over-collateralised lending with on-chain assets and expanded to off-chain instruments focused on institutions. ParaSwap could theoretically look towards offering infrastructure that settles bonds and t-bills between counterparties that know one another. In both instances, the assumption is that there will be a market for

Institutional clients leveraging DeFi or

Newer instruments are coming to market, as we saw with NFTs in the last cycle

Creative Destruction and Moats in Networks

It helps to see how other industries have evolved to learn how the newer ones may evolve. The payments industry has three key players – banks, payment networks, and payment aggregators.

Banks are where users hold their funds. Wallets in Web3 play this role.

Payment networks like Visa and MasterCard provide infrastructure and networks for processing transactions between different stakeholders like merchants or card issuers. They are similar to a blockchain a payment takes place on.

Payment aggregators allow merchants to accept payments from multiple payment networks.

The likes of Visa and Mastercard make money by charging a transaction fee. Visa owned 60% of the payments network space, followed by Mastercard (25%) and AmEx (10%). The network effects of payment networks are a difficult entry barrier to overcome for other new entrants; therefore, it is difficult to disrupt incumbents and change practices like charging a transaction fee.

Payment aggregators like Stripe, PayPal, and Square allow merchants to accept payment via payment networks like Visa. But they have not launched a direct competitor to Visa or Mastercard.

Unlike payment networks, aggregators earn revenue via integration or setup fees which cover the cost of merchant onboarding and value-added services. The point is aggregators facilitated more activities instead of just connecting different payment networks. Over time, their value-added services are what attract customers.

The further a business moves from the consumer, the lower its probability of setting the price. ParaSwap's current challenge is addressing the obsession with an SDK-based approach to growth. This obsession can reduce its ability to capture value for itself. The only way to change that equation is through driving volume.

Amazon can renegotiate its pricing with vendors due to the volume it offers. Blur changed how we thought of NFT royalties because of the volume they drive. If ParaSwap can command a substantial share for emergent DeFi primitive volumes (like options or insurances), chances are high that it would be able to set a higher fee for itself in exchange for product discovery.

Creating a moat through pricing alone does not happen in open-source money networks. What may happen is - if a single aggregator can plug into multiple products (like wallets, Dex, and AMMs), it may be able to facilitate the movement of liquidity across all of them. In turn, it could offer better pricing for users. By default, that should mean users would have an affinity for products powered by a service provider.

In such a system, ParaSwap's growth is contingent on its ability to onboard service providers and applications whilst using its token to incentivise the behaviour of users through products it is embedded in. Instead of users trading on ParaSwap, even a wallet that uses an SDK embedding could be given rewards or incves.

This creative destruction of the self, where ParaSwap evolves from being a standalone price aggregator to a multi-asset, thin embedded protocol servicing multiple products, is where the opportunity lies for ParaSwap. In that pursuit, they may have to integrate (or build) bridges and data layers for better price feeds.

The way I see it, their focus on business applications is likely the way to build a moat. More applications can translate to higher trading volume. This, in turn, should help them reduce fees & lower fees, and should help attract more users. We will slowly start seeing applications built on Ethereum take a page from the ecosystem playbook most L1s have been perfecting over the years.

It may seem far-fetched. But consider that when Blur launched, much of its orders occurred elsewhere. As user behaviour changed and threshold liquidity was reached, the marketplace switched to settling orders in-house. ParaSwap is already at a point where it can absorb and close out orders without sending them elsewhere.

The moat is not in pursuing the supply side more but in building the demand side. The demand side comes only through more users, wanting to use more on-chain instruments from more DeFi platforms at the lowest price possible. It is almost as though DeFi primitives will have to do with financial instruments, what Amazon did with consumer goods.

That is the challenge that lies ahead for Mounir and the team.

Disclosures

I am an investor in LiFi - one of the bridges mentioned above.

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

Telegram and Pitch Decks

Join in with ±4000+ researchers, investors, founders & overall great human beings. We don’t exactly talk much, but it would help you stay close to what we are focusing on & connect with others building cool things.

We have been actively deploying money & advising a small crew of founders. Contact us through the form below to go 0 to 1 with your early-stage venture.

Very nice job, Thank's

Great piece 🔥