The YFI Trade

Reflexivity or something like that.

Hello!

It was September 1992, and George Soros had almost broken the British Pound. Twelve member states of the European Communities had signed a treaty in February to establish the European Union. Soros was sceptical of the UK’s decision to join the European Union exchange rate mechanism (ERM) that fixed currency exchange rates to the German Mark (DEM).

The UK was already facing recessionary conditions, and keeping currency pegged to the German Mark meant its exports were not competitive enough (since the currency rate was propped up). Low growth and an unstable political environment meant that raising interest rates was insufficient to keep speculators from shorting the pound.

Despite the central bank’s efforts to buy back pounds from the market and push interest rates to 15% to attract foreign capital, the pound kept dropping against currencies like DEM and USD. Soros was one of the first investors to see the problems in Britain joining the ERM. He built a massive short position on GBP and publicly spoke about how joining the ERM and establishing the EU was a bad idea.

He ended up making over £1 billion through this trade. The point of the story is that in free markets, participants are free to bet on what they want and use conditions to tip the scales in their favour. Soros’ outspokenness against the peg rallied other investors behind his position, eventually leading to the UK withdrawing from the ERM.

Something similar but of a tiny magnitude happened with YFI and dYdX on November 18, 2023. A well-capitalised participant saw a market inefficiency and exploited it for their benefit. Before I dive into how and what happened, a small note on liquidity: it is one of the most critical puzzle pieces for mature markets. It can be broadly broken down into the following:

Slippage – This is the difference between the trade’s expected price and actual price. For example, say a trader wishes to acquire ETH worth $10k at $2000 per ETH but gets the order filled at an average price of $2010. The slippage is 10/2000, or 0.5%. High-liquidity venues offer lower slippage.

Depth – This measures cumulative limit orders on the bid or ask side. For example, say ETH is trading at $2000, and the dollar value of ask (sell) limit orders until $2200 is $10 million. Then, the 10% depth for ETH is $10 million. Another way to look at this is it will take $10 million worth of buying to push the price of ETH up by 10%. The higher the depth, the more liquid the asset.

Low volatility is a trademark of mature markets. Low volatility usually means high liquidity, and it’s difficult to manipulate prices in such an environment. Capital mercenaries often make their moves during times of low liquidity.

Low liquidity invites volatility

Over the years, liquidity for major crypto assets has significantly improved. For example, the 2% depth for BTC across some large exchanges is over $100 million, while for ETH, it is ~$80 million. However, the story becomes very different as you go down the list of assets by market capitalisation and popularity with institutions. The chart below shows the value of a handful of DeFi tokens that can be sold at 2% and 10% depths, respectively.

On November 18, across Binance, Coinbase, and Bitfinex, the 2% and 10% depths for YFI were ~$50k and ~$180k, respectively. Consequently, a motivated actor could systematically buy, increase the price and interest in the asset, and suddenly sell YFI, profiting in both directions.

A different return profile in the APAC session from November 15 onwards suggests that a single actor was responsible for driving the price of YFI higher. The chart below from Velo Data offers some hints at how the price of the token traded across trading sessions. We can presume that it was a single actor (or coordinated actors) moving the price, given the proximity of time for the price action on the asset.

Meanwhile, the YFI open interest (OI) jumped from ~$20 million to ~$85 million across Binance, Bybit, and OKX. At the same time, YFI OI jumped from $0.8 million to $67 million on dYdX, higher than any other exchange (even Binance was $44 million).

Around November 14, someone deposited ~$640k on dYdX via multiple addresses associated with the address that withdrew USDC on November 18. Subsequently, YFI price jumped ~60% to ~$16k and then dropped ~50% to $8.2k. The same address then withdrew $6.2 million. One can speculate that this actor managed to long and short YFI on dYdX.

As the price of YFI plummeted from ~$16k to ~$8.2k, dYdX could not liquidate long positions successfully.

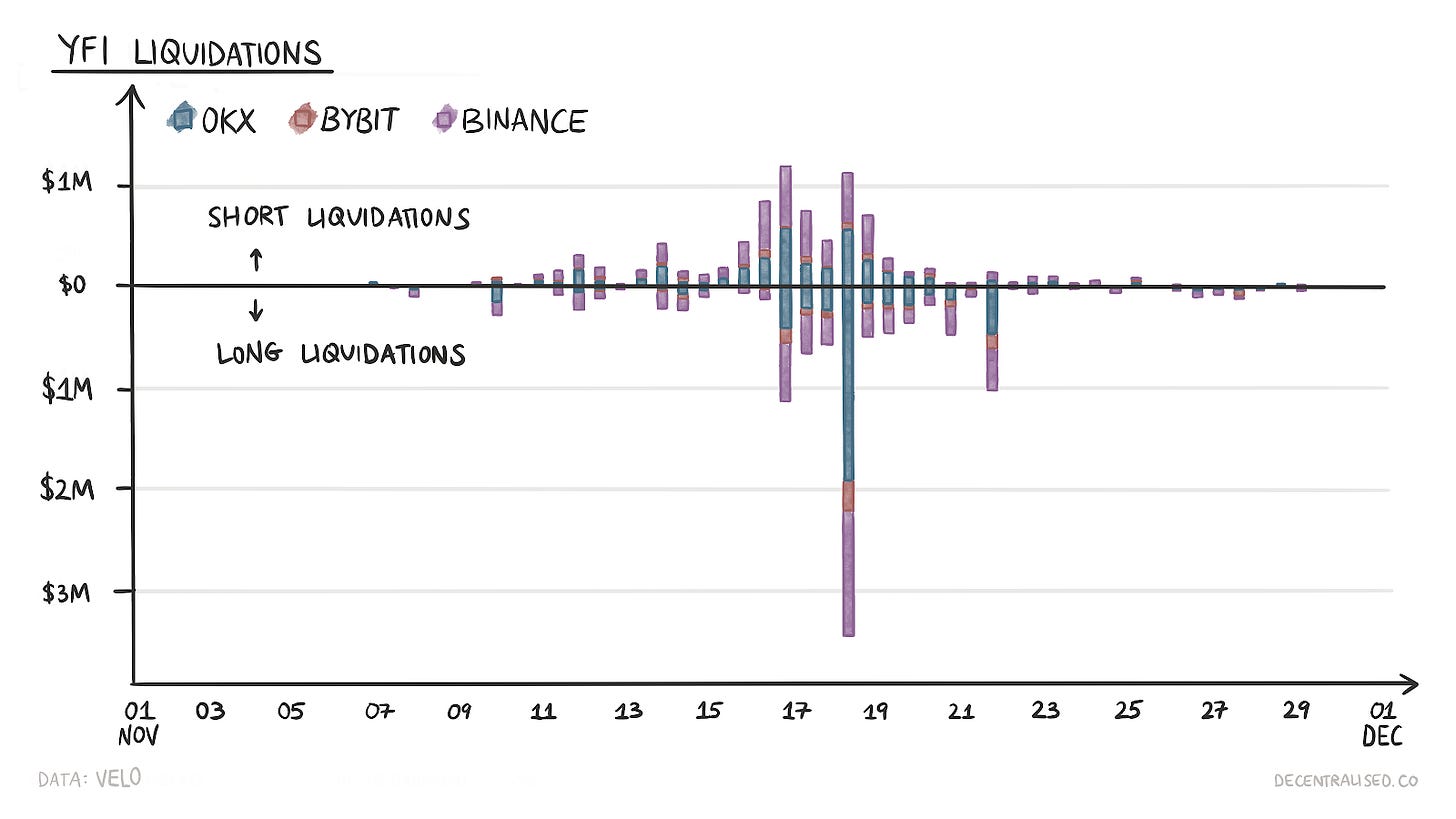

Consequently, the insurance fund lost $9 million. This $9 million might have been the profit of other traders on the exchange, but it could not come from loss-making traders since their positions were not liquidated in time. CEXs witnessed ~$3 million worth of long liquidations simultaneously.

Why do DEXs need insurance funds, and how do they work? Whenever there is leverage, the user trades more capital than they have. When you use 4X leverage (that is, you are borrowing 3X capital), and the price moves 10% in the direction you bet on, you make 40% instead of 10%. The downside, however, is that you also lose more with leverage than you would have otherwise if the price goes against you.

For example, say that Sid wants to long ETH with leverage. He deposits $2k as collateral and longs ETH with 4X leverage when ETH is at $2k. If the price goes to $2.5k, Sid makes $2k. But if the price drops, Sid loses $4 for every $1 down move. If the price hits $1.5k, his position becomes worthless.

Exchanges employ something called a maintenance margin, so before the price hits $1.5k, the exchange will start liquidating Sid’s position.

Let’s assume, due to the maintenance margin, the liquidation price is $1510. But order book DEX, like dYdX, needs another trader willing to take over Sid’s position. What happens if the exchange cannot find this trader on time?

Let’s say that by the time a trader takes on the position, the price is $1490. Sid’s position is –$2040 when the maximum he could lose was $2000 because that was his collateral. The $40 gets bridged using the exchange’s insurance fund. This scenario typically happens with sudden price drops or when the oracle fails to fetch the price on time.

Exchanges also employ funding rates to balance longs and shorts. When there are more longs (than shorts), they pay shorts to hold their positions, and vice versa. When the YFI price dropped, short interest rose significantly, captured by the funding rates. The funding rate is a mechanism to ensure that the futures price traces the spot price. How? Perpetual futures are regular futures without expiry.

In traditional markets, futures come with expiry dates. As we get closer to expiry, futures prices get closer and closer to spot prices, as spot price is used for settlements. But when there’s no expiry, there needs to be another mechanism to ensure that the instrument closely tracks the spot price.

Enter funding rates. When the futures price is higher than the index price (typically the spot price), in other words, when there are more longs than shorts, longs pay shorts to hold their positions. Shorts pay longs when the futures price is less than the spot price. Depending on the exchange's design, funding rates typically change every hour or 8 hours.

The negative APR in the following chart shows shorts paying longs. In this case, the short interest rose significantly, taking annualised funding rates shorts had to pay to ~140%.

Why YFI, and why now?

As shown in the depth charts, YFI had one of the lowest depths among major DeFi assets. A low depth means making the price go your way is easier. I think selling it short was not that big a deal. The 10% depth was around $180k on November 18, meaning you only needed to sell $180k worth of YFI to drop the price by 10%.

The trick was increasing the open positions (OI) to a point where a price drop of 10% triggers a cascade of liquidations, causing the price to drop much more. Remember how exchanges liquidate positions? As more long positions get closed, the price drops further, triggering more liquidations. See how funding rates rose to ~100% around November 18? It indicates that a large long interest had been generated at that point.

The market sentiment turned positive as broader prices increased through October. Yearn announced high Prisma rewards and teased its V3. The confluence of these fundamental developments, improving market sentiment, and low depth to nudge the price in either direction made YFI a much more lucrative target than other assets.

Clever trade or manipulation?

The dYdX exchange launched an investigation into this incident and claimed that it was a targeted attack. I don’t know whether this qualifies as theft or wrongdoing. Technically, nobody stole anything here. In financial markets, participants take positions with their capital and nudge other participants to rally behind their positions with several clever, non-illegal moves.

The difference between a clever trade and illegal action lies in whether the participant misleads other participants to believe in the manipulated or artificially affected price.

When there’s more information (as promised by dYdX and its founder), we’ll try to understand why this was an attack and not just a good trade. Artificial price manipulation is illegal in financial markets. Something similar happened with Mango Markets in 2022. The protocol allowed users to borrow against unrealised gains. Avraham Eisenberg manipulated the price of the $MNGO token and borrowed $115 million against unrealised gains from the Mango Markets protocol.

He was later arrested for charges of commodities manipulation and fraud. The crux of the dYdX situation lies in whether market manipulation can be proven. If yes, criminal charges can be filed against the trader who orchestrated this trade/attack.

What next?

This incident is a reminder that low-liquidity assets (like COMP, as shown in the charts above) will likely face these moments and why seasoned investors and traders are wary of such assets. Financial markets usually improve when clever and efficient traders bring out the inefficiencies in the market, and others try to copy them. When everyone tries to make the same trade, the liquidity improves, and inefficiencies get bridged.

Since the incident, YFI’s price has remained flat. dYdX has launched its V4 on its Cosmos-based app chain and has taken a cautious approach while listing assets. So far, more liquid assets have been listed. Exchanges typically raise margin requirements to avoid YFI-like incidents.

Although dYdX did the same, it was not enough. When this happens on tradfi exchanges, KYC and other fraud monitoring tools help exchanges mitigate the damage. One of the advantages of DeFi is that funds can be traced easily. The proof never leaves the chain, whereas in traditional settings, using different accounts (where many KYCed accounts are bought) cannot be ruled out. In this case, proving wrongdoing is extremely difficult.

I don’t know how real-time fraud monitoring can work in DeFi. However, one way is to track suspicious wallets and their associated addresses; the watchdog is on alert whenever these accounts deposit funds onto exchanges like dYdX. Of course, you always work with assumptions and probability, as you never know whether the same entity controls thousands of addresses. But it can perhaps help contain damage to a certain extent.

Going back to working on a Solana long form,

Saurabh Deshpande

Acknowledgement: I want to thank our data partners, CCData and Velo, for sharing data with us.

If you liked reading this, check these out next: