On Aggregation Theory And Web3

Why collapsing the cost of trust and verification is profitable.

This piece was made possible with a sponsorship from Nansen. The platform saves analysts and traders hundreds of hours each month by allowing them to grab network level data with a simple click. No APIs, no going through network scanners or pulling contract addresses. Nansen visualises network level data on user behavior & transactions in a fraction of the time their peers do. Get started with a trial here or simply play with their dashboards here.

Hey,

TL:DR - Me and Krishna from Quantstamp show how multiple multi-billion dollar firms within web3 have been built through collapsing the cost of trust and verification. Drop me an email if you read this and decide on building something cool. We may just be able to put together your seed round 💰

In today’s issue, we zoom out a bit and look at Web3 through the lens of Aggregation Theory. It is a bit long, but stick along, and we will break down how we believe the next decade of investing in blockchains will happen.

Ben Thompson first proposed aggregation Theory in 2015 to explain how the Internet has contributed towards the evolution of markets. Ben described it like this some seven years back:

The value chain for any given consumer market is divided into three parts: suppliers, distributors, and consumers/users. The best way to make outsize profits in any of these markets is to either gain a horizontal monopoly in one of the three parts or to integrate two of the parts such that you have a competitive advantage in delivering a vertical solution. In the pre-Internet era the latter depended on controlling distribution.

The fundamental disruption of the Internet has been to turn this dynamic on its head. First, the Internet has free distribution (of digital goods), neutralizing the advantage that pre-Internet distributors leveraged to integrate with suppliers. Secondly, the Internet has made transaction costs zero, making it viable for a distributor to integrate forward with end users/consumers at scale.

We believe the theory deserves a revisit from the lens of someone working in Web3. We have seen behemoths like Ramp, Stripe and Spotify being built through the collapse in the price of distribution and collecting payments. But how does it apply to Web3 firms? We propose that in addition to collapsing the cost of collecting payments, blockchains can reduce the price of verification and trust. This enables the creation of multi-billion dollar entities that were historically not possible. The new era of blockchain based aggregators also help drive innovation at the protocol layer, and enable a new business model: Hyperfinancialization-as-a-Service. But before we go there, let’s break down Aggregation Theory for our readers that have not been following Ben Thompson.

Bringing Markets Closer

Here's a breakdown of Uber through the lens of Aggregation Theory. Historically, the vendor (supplier) <> buyer (demand) relationship was hyper-local and had a cap on the number of customers a driver could potentially have. This is why they could get away with treating you terribly. There were limited choices on who could possibly offer a ride. The supply side was messy in that it had minimal signs of reputation, suffered from ineffective pricing in many cities and was unpredictable. Uber came along and organised the supply side.

It was a curated subset of users whose reputation was verified and tracked on an ongoing basis instead of one comprised of random drivers. Think about the information you get each time you request a ride. You know how many times the person has picked people up, the driver's average rating, and the exact amount you can expect to pay.

Why did this shift from taxi unions to in-app drives happen? Because Uber controls the supply side through their app. Users looking to book a ride prefer the convenience of remotely hailing a cab instead of waiting out in the streets and being rejected by random taxi-men. This model works because the internet allows Uber to scale globally from their comfortable offices in San Francisco or wherever the new hip place to build a venture is.

It also enables Uber to collect payments and take a fee-cut for themselves without relying on regional partners to do that for them. The rise of digital money accelerated Uber's adoption. If we were still paying for our rides predominantly in physical cash, it is unlikely that Uber would have been a thing.

The largest firms on the internet today can be linked to aggregation theory. AirBnB, Deliveroo, Spotify, Steam, Amazon and Twitter have each upended messy markets through the power of the internet. Aggregators accumulate so much value because they can organise what are typically large, chaotic markets. Newspapers? You had thousands of them opining differently, often with inaccurate sources. Your feeds replaced them.

What about renting a house in a small town for a few months? Airbnb made it "okay" to live in a stranger's home. Customers trend towards these aggregators as they can expect the same level of service, quality and standards with a very varied list of vendors. You get the safety of a familiar platform and optionality that spans the entire market. Going back to my Airbnb example, users know that they can register a complaint with the website to get a refund if a booking goes wrong. Amazon? The refund almost happens instantaneously.

Aggregators enable vendor reputation and moderation. You can look up reviews when you buy something on Amazon. In exchange, they take a cut of the transactions that occur on them. As a platform goes digital, the frequency of transactions tends to increase. This allows aggregators to run with much lower take rates than the cost of physical experiences. Why? Because the cost of delivering a digital good (like movie streaming) is a fraction of what a physical experience (like a flight) would take.

Users can only take one flight at a time. During the same flight - you may see a user streaming multiple movies. Or if they are like us, they may buy numerous altcoins or NFTs they will regret purchasing as soon as they get off the flight. Hopefully, you have a good sense of what aggregation platforms are and how they scale. Now let's return to Web3.

Collapsing The Cost of Trust

Much like the internet collapsed the cost of distribution and collection of payments, publicly verifiable blockchains have collapsed the cost of verification and trust. Practically all of the enormous businesses we see in the context of Web3 are built on this principle. Blockchains make it possible for anyone to query and verify if a digital good being sold is genuinely from the source it claims to be. There is no counter-party risk for digital consumption goods like NFTs that are sold through a blockchain-enabled platform because verifying a smart contract ensures you are getting the exact good you are paying for.

What does this signify for those running aggregators in Web3? It means it costs a fraction of what it does in Web2 to verify and trust vendors when it comes to sales of digital goods. When Netflix or iTunes initially launched, they had to spend months or years negotiating contracts to ensure they could go to market with a large enough inventory of digital goods that would attract users.

Even today, Netflix spends some $16 billion on producing content in-house based on their users’ data. As the size of these aggregators scaled, they became the best place for digital consumption goods to be sold. After a decade’s worth of work, owning the distribution gives them that advantage.

Some interactions are not possible in Web2 aggregators because of the inherent friction introduced by siloed databases and data that is not open. For example, you cannot browse for property listings through Zillow, and subsequently make an offer on it and move on to refinancing the asset all within the same platform. You would have to go to another venue like Figure, and run through their various compliance and onboarding procedures that are unique to each platform.

It also makes it much harder and more expensive for developers of other applications to easily tap into your aggregation and build new interesting services on top. On-chain identity, data and verification standards can solve for this, and enable Web3 aggregators to be much more efficient than their Web2 counterparts.

In stark contrast, OpenSea does not spend much worrying about the licenses. They can almost instantaneously verify that a third party’s NFT comes from a legitimate source and track how it moves across its userbase. What about Uniswap? So long as the user accurately adds the token’s address, there is no need for human involvement in verifying if a token being traded on it is legitimate.

Blockchains abstract away the verification layer and collapse the cost incurred. Does trust command a premium on its own? I think it does. Let’s consider a few instances where a platform owns the commercial rights and compare with one that does not. Music would be a good theme so we go with Spotify and Soundcloud as examples.

One has been the go-to platform for streaming music worldwide, while the other is occasionally used to find something motivating to listen to at the gym. Soundcloud, by all means, is an incredible business, given its focus on community and enabling new artists to be discovered. But if seen purely through the lens of revenue generated, you will see how the two businesses differ.

The two businesses have different ways of operating. Spotify claims to have 406 million monthly active users of which some 180 million are premium paying. They have a margin of some ±25%, so you can discount the $9 billion annual revenue you figure in the chart below. But even when accounted for that, you will notice that the revenue for Spotify is a massive multiple of what Soundcloud holds.

Part of why this is the case is that Soundcloud requires volume in terms of user streaming to scale on ad-driven revenue. But if all of the users are on premium platforms, why would they come to Soundcloud? This is a phenomenon you can see across product categories.

Amazon as a standalone platform commands more in e-commerce volume than Shopify storefronts do. Steam - the storefront for games - takes in more revenue than individual gaming studios. Why? It boils down to customers choosing stores with the maximum optionality and minimum amount of friction. The greater the number of choices, the higher the possibility that commerce concentrates on an avenue, making it easier for the platform to offer more optionality while keeping costs low thanks to the scale of the operation. This is the flywheel of modern commerce. Max Olson did a great job at visualising how these work on Twitter a while back.

Web3 is interesting because it changes the unit economics of verification and trust. Historically, aggregators would acquire intellectual property rights for the most desirable digital consumables. As we will see in a piece soon, in emerging markets like India, holding the streaming rights for Cricket paved the way for television networks to scale. Blockchains have enabled platforms to prove provenance and authority of issuance from anyone on the web at a fraction of the cost.

This means the expenses incurred in legal fees and time spent through bureaucracy is now replaced with on-chain verification, identity and verification. This principle will be at the crux of what makes aggregators in Web3 massively influential. Don’t believe me? Let’s look at some of the aggregators within the ecosystem today and how they use blockchains to their benefit.

Aggregation in DeFi

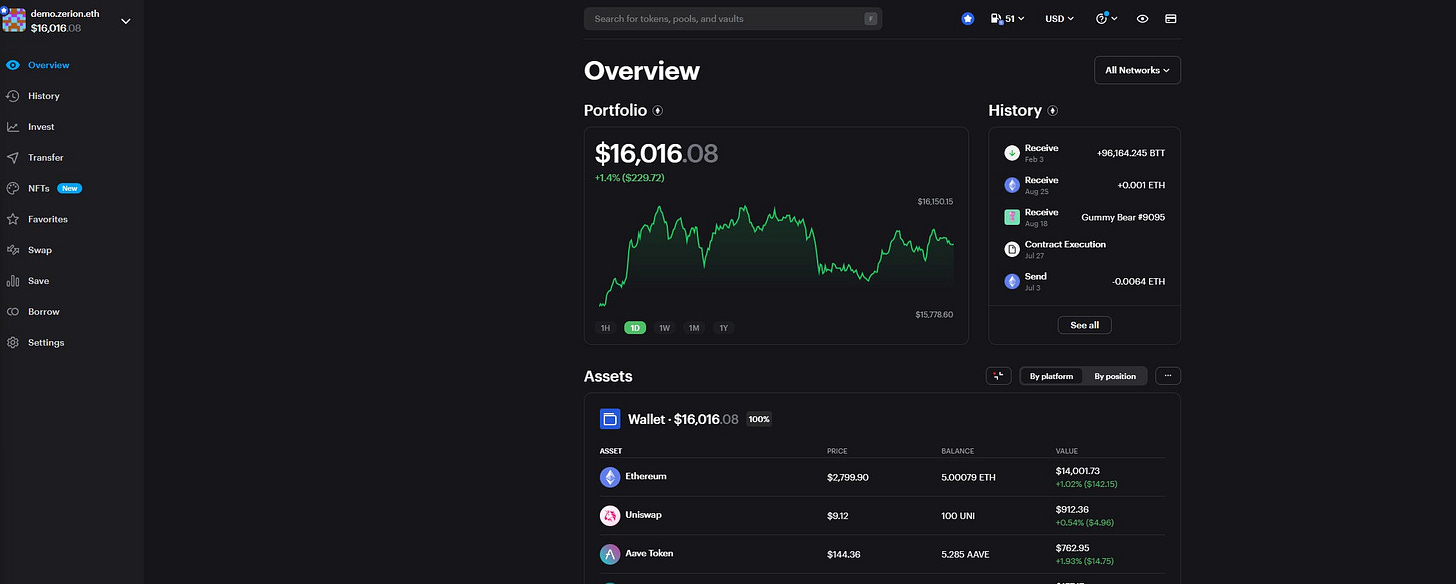

Zerion is a wallet interface focused on enabling users to track their portfolios. The product currently tracks NFTs, allows swaps, and gives users a look at how all the tokens in their wallets are performing. Interfaces like those offered by Zerion are quickly becoming the “home page” for DeFi. They allow users to interact with a complex host of apps without going outside the interface of a single website. In addition, these interfaces eliminate the high risks of phishing, losing keys and signing the wrong smart contracts by allowing users to interact with them directly through their interface. They help users access functions like lending through curating protocols, and also drive innovation at the protocol layer by offering more choices to customers that offer them competitive pricing and features. It would be safe to suggest that assets worth a few billion dollars are managed through Zerion’s interface.

How much of that risk is with Zerion? None. They don’t custody the assets and they don’t manage the smart contracts. Instead, they are responsible for embedding each of these protocols into the product to create a super-app. According to a recent press release, they interface with some 50,000 assets across 60 protocols. Comparables like DeBank, Frontier and ImTrust have been at the forefront of enabling more retail participants to find their way around the complex Web3 ecosystem.

How? They reduce the trust barrier required to use an app as an end-user assumes that the interface creators have already exercised due diligence. Secondly, they enable new apps to be discovered far more smoothly than through complex web of information platforms like Twitter. Lastly, and most importantly, they combine the ability to club multiple DeFi DApps in a single interface. They have also begun integrating on-ramps and tax software as users’ needs in the industry evolve.

I have taken Zerion as an example here as it is a centralised entity that acts as an interface to plug in with multiple defi DApps. However, aggregation in DeFi runs beyond that. Here are some examples :

Orderflow - 1inch and Matcha.xyz allow users to find the best price for assets that need to be traded without going to individual platforms. They do not custody the assets used for trading themselves but seek liquidity from third-party platforms. Matcha has taken this one step further by integrating a request for quote model in the product. They have done about $42 billion in cumulative volume across ±900k orders so far. This feature allows centralised market-makers in the back end to quote prices for large order sizes, thereby bringing the experience closer to what a centralised exchange like Binance can offer.

Yield - The holy grail for DeFi has historically been the ability to provide yield. The large risk lending or decentralised exchange platforms have is potentially getting hacked. But what if you could build interfaces that allow users to deploy capital in pools while not necessarily holding the assets yourself? Rari, Alpaca and Yearn Finance do just that. Rari alone has deployed $922 million through Fuse pools for a sense of scale. Instadapp takes this one step further with its user experience. The product allows users to manage debt positions or deploy assets into yield-bearing pools using a single interface. They manage around $5 billion worth of assets across the likes of Maker, Compound and Aave through their interface.

Aggregation of The Metaverse

Chart source : Gem Master Dashboard by @bakabhai993

NFTs are interesting from the point of view of aggregation. You have a digital good with transaction finality and on-chain provenance of intellectual property. Please don’t curse me. I will explain it without the jargon. Given that users cannot reverse blockchain transactions, a user buying an NFT almost certainly does not have to worry about losing what they purchased to fraud unless the NFT itself is a duplicate.

They can also verify that it is coming from the right source almost instantaneously. Unlike traditional art markets, you can almost instantly see what the floor price of an NFT is and who its past owners were. These make NFT aggregators incredibly powerful in terms of how they can interact with market participants.

Consider Gem, for instance. The aggregator itself holds none of the NFTs listed on the platform. They use Dune to give analytics to their users. Once you click on a collection, the interface allows you to bid on listings directly in Opensea and LooksRare. Now, this is where this gets even more interesting. Aggregators like Gem become the place for price discovery as users are essentially discovering and tracking their portfolios and bidding through them.

In the future, they’ll also cover features that blur the lines between DeFi and NFTs through lending and automated inventory management. The traditional art or physical market have some of the previously mentioned constraints relevant to Web2 aggregators that prevent them from offering these services at low friction and cost. In addition, some of the other verticals like Gaming and Metaverse do not even have historical analogs - Web3 aggregators will be the first to support and enable efficient markets in those categories of digital assets.

Over time, they can be influential enough to determine which NFT set gets “discovered” as essentially what they are accruing is the market’s attention. How much is that attention worth? I don’t know yet, but it is valuable enough to have driven $400 million in volume through the platform alone. Gem is also influencing the market share of the underlying NFT marketplaces themselves. Because users are marketplace agnostic and will buy and sell assets wherever there is a favorable bid/ask. For example, LooksRare’s market share on NFT volumes went up in relation to OpenSea since gem was launched.

For an idea of how quick aggregation can scale, consider this tweet below from Vasa flexing the number of platforms Gem shows NFTs today from.

Sidenote: He’s a great guy. You should follow him

We believe that aggregation of NFT linked assets will happen thematically. For instance, Parcel allows individuals to bid on real estate linked NFTs. Similarly, there will be separate marketplaces for gaming linked NFTs. There are gaps in the market for sports, music and film-related NFTs. Part of the reason for this is that the thematic focus on asset types allows founders to curate communities around them. It creates an initial flywheel for enabling transactions through the platform itself.

Aggregating Data Markets

We have discussed how aggregation theory in the context of Web3 creates entirely new marketplaces. Web3 linked aggregation models work because they focus primarily on digital assets. One sector that can be considered more "digital" than tokens and NFTs is that of data markets.

Data markets in Web3 are attractive because:

all data sets offered can be queried and verified instantaneously by a third party

they directly embed with multiple third-party apps and therefore scale exponentially

the cost of adding each new chain typically tends to decrease

the delivery of the product (data) is instantaneous

the cost of maintaining the network infrastructure is outsourced in the case of protocols

You can break this sector down into two variations. One of them offers the end-user direct access to the data through charts and queries that present the information in a consumable way. These are centralised businesses like Nansen or Dune. Nansen built a business by focusing on the interface. Their centralisation aspect pertains to the labels on 100million+ wallets and the chains they index. Users themselves don't create the queries. The team at Nansen handles these, but once the queries that pull the data are made, they can be replicated across chains. So the unit cost for expanding to each new chain trends downwards. The initial investment is in labeling and setting up queries that lookup the top holders, smart contracts or wallet interactions on each chain.

Where Nansen excels in giving users pre-defined queries without any hassle, Dune wins by giving an infrastructure on top of which anyone can query. Nansen has constructed their moat based on their extensive work built around labeling over 100 million wallets. On the other hand, Dune has built a moat through its extensive userbase that fights tooth and nail to be at the top of its leaderboard.

It would be relatively easy for a third-party platform to replicate the data Dune holds today, but good luck replicating the community members without an active incentive system. Both platforms are unique in that they can (i) sell data digitally, (ii) do so in an almost instantaneous fashion and (iii) have limited marginal costs in expanding the number of chains they support. There are protocol-based peers in the sector.

Covalent, Graph, Pyth and Chainlink are protocol-based alternatives to the same model. Each of them supports DApps across the ecosystem and respond to millions of queries on a routine basis. Protocols at the data layer are even more fascinating because they don't necessarily own the hardware infrastructure to make these data sets available. Instead, the indexing of the data set is done in third party infrastructure, which is incentivised through the protocol's native tokens. In a traditional data venture, the cost of running infrastructure eats into the firm's profitability. In the case of protocols, the perceived "value" of the network increases with each new node that hosts data on these networks as the possibility of the entire data network going down diminishes.

The Next Decade of Aggregation

Let's revisit the core argument of this piece before we wrap up. We believe that blockchains will enable an entirely new category of markets that are able to verify on-chain events instantaneously. This will collapse the cost of validating intellectual property at a massive scale and thereby create new business models. Present-day Web3 aggregators provide interfaces that show on-chain data and allow users to interact with smart contracts from multiple platforms. They don't own the risk of custodying these assets and typically do not bear exponentially higher costs for supporting additional networks. Covalent and Nansen are able to generate exponential value through adding each new chain - which is usually a linear expense.

The core proposition of Web3 aggregation over the next decade will be in streamlining large, messy processes with multiple counterparties in systems with low trust. One instance of this occurring has been AngelList. The platform has structurally collapsed the amount of friction involved in putting together a venture round through combining legal, banking and LP management in a single interface. How much is that worth? Around $4 billion as per their latest round. Large, messy markets with multiple moving parts are hard to aggregate at scale unless you have time or capital. AngelList took roughly 8 years to build its monopoly, while Uber had to raise some $25.5 billion to become today's behemoth. I believe blockchains will collapse the unit economics around this and hyperfinancialise the process. Clubbing the eradication of inefficiencies in what has historically been long, chaotic processes with incentives that allow people to profit them can be a powerful mix.

This has already been happening in some emerging markets. In an upcoming piece, we will shed light on a business aggregating the stack required to execute, verify, and validate traditional contracts in Africa. Aggregation in the context of Web3 reduces the surface area where corruption and inefficiencies can creep in. Emerging markets that have been historically riddled with corruption and a lack of transparency stand to benefit the most. Think about DAOs. Today, it takes 5 minutes and $200 to put together one on Ethereum. In stark contrast, it has taken me six months and endless calls to get a firm registered in India. Part of that delay is the lack of trust and ability to verify my data instantaneously. Blockchains help collapse that gap. We are merely manufacturers of trust-production machines for trust-deficit societies.

P.s - Feel free to steal this piece and remix it. We are looking for deep dives on how blockchains are enabling aggregation in different markets. Come hang out in our Telegram and discuss if you have any thoughts on this.

Joel

Disclosure : The authors of this piece own significant exposure to a number of ventures mentioned above.

Nice article, thanks for sharing.