How To Build Product-Community Fly Wheels

A founder's guide to making people care

Some housekeeping, as always.

Today’s story is an extension of several stories from the past. In my last issue, I wrote about how people - not decks, determine outcomes for companies. I wrote that story with an emphasis on founders.

Today’s story sheds the spotlight on users. In particular, I explore how a company we worked closely with fostered its community over a decade and why founders should focus on their community to scale.

This is a precursor to a collaborative piece we are doing with several CMOs. Over the next month, I will be speaking to senior leads at multiple protocols to understand how they build their communities. My intention is to build a series of stories that guide founders as they build their firms.

If you are an early-stage operator looking to build with us, make sure to reach out via DCo.build.

Also, the podcast we run has been trending in UK, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Spain, Italy and Finland. We topped at #15 in UAE and #36 in India. We are now taking sponsors for it. Drop me a text on Twitter if you'd like to talk about it.

Hey there,

A few weeks back, I flew to the town I grew up in—Pune in India. It is a hotbed for many tech companies. Far from the heat in Dubai, I was comfortable enjoying the monsoon in the region. But natural beauty was not what took me there.

The intention of me stepping out of our office was quite simple. I was headed to SuperGaming’s office. We have been advisors to SuperGaming for over a year now. They are one of the region’s largest game publishers, with a little over 100 million active downloads and a roster of over 20 games. Five of which have over ten million downloads. They get the metaverse, in ways we don’t.

I have been following Roby John (their CEO) for a while and admire his approach to building community. Any time we speak about the product, he would talk at length about how they are using their community to aid what they are building. They have no tokens or protocols, only games that are loved by many.

So I spent two days trailing him at their office and speaking at length over samosas and hot filter coffee about his journey as a founder. We discussed what it takes to build communities of scale and why they matter. This is over a decade's worth of Roby's learning summarised in a few thousand words.

For those in a rush, here's what you can expect from the piece. I break down how communities are built at each stage of a venture’s growth.

I explain why, at seed stages, you should fly under a known, more recognisable flag.

We explore how talking to users and making them feel seen and heard can make a huge difference as you scale.

And I explain why "culture" is the final battle for firms to take on as they grow.

Don't worry. I won't leave you with abstract references. We'll go through 15 years of Roby's experience building companies over the next 15 minutes.

Inception

It’s 2011. A young, idealistic founder from India has made it to YCombinator. He is not new to the world of startups. At 21, he was closing million-dollar consulting contracts during the dot-com boom days, but building something new is exciting. Roby was working on a game that helps users understand math better. They were specifically building for the wave iOS devices that were coming online. In particular, apps for iPad.

There was little success in the early days, but he quickly noticed that some of his younger users had posted videos of his product on YouTube.

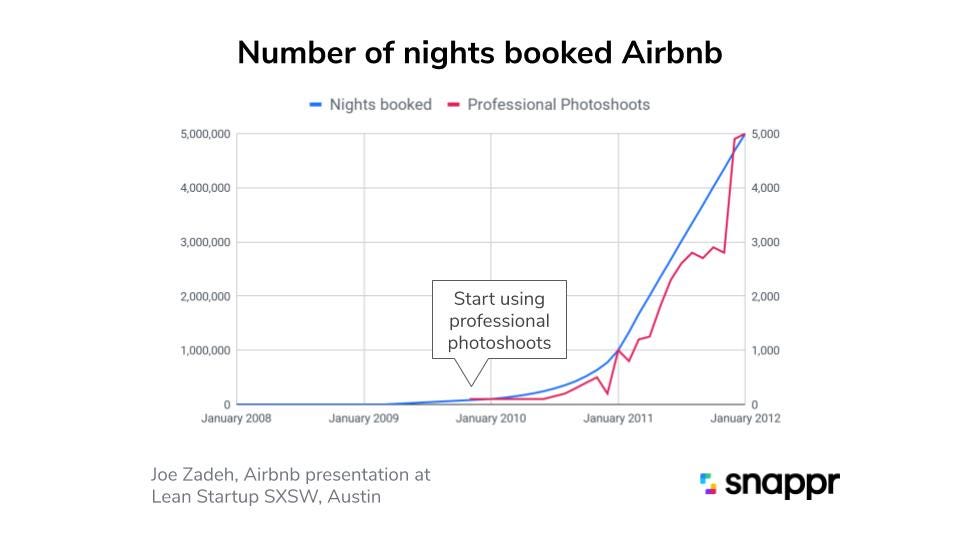

It gave Roby an aha moment. This was when Airbnb's founders were flying to New York to take pictures of their user base's properties. The images uploaded by users were often less than appealing, so the founders took the effort to go do the shoot themselves for their hosts. It made onboarding the hosts more personal. It made believers out of users. Roby took inspiration from this.

He realized that empowering users to distribute his product would be the difference between relevance and quick death, so his focus naturally shifted towards building a community.

If you are a smaller studio from India, your odds of being recognised right away are low. This was before smartphone adoption and access to the internet were easily available across the globe. Gaming back then was a lot like crypto today. People had their share of biases against people working on games.

How, then, do you build a relatable brand?

One way would be by flying under a more recognised name.

Recognition

In 2012, Roby and his team raised a small round of $1 million for what was then called June Software. (The company would eventually merge with Super). The investor base included a prominent publisher of the day named Backflip Studios. Having them on board opened up access to intellectual property that was loved by many users at the time. Think of it like this: A user may not search specifically for a game studio's name.

Very few people recognise Rockstar Games, for instance, but kids often search for terms like "Spider-Man" in hopes of playing games involving their favourite character. We saw this when Niantic partnered with Pokemon GO to build a breakout success in AR. Studios routinely tap into great IP for discovery.

So Roby set out to build games like NinJump (with Backflip's help) to acquire users at extremely low costs. In those initial days, this collaboration helped users discover the games June software was creating. More importantly, it exposed Roby to how game studios operate. He was getting both discovery and operational expertise in one shot.

Even today, Super’s platform powers Pac-Man around the globe, through a collaboration with Bandai Namco - the publisher behind other titles like Elden Ring, Tekken and Dragon Ball. They joined SuperGaming as an investor in 2023.

A version of this used to happen with blockchain protocols, too. In 2021, being on Polygon meant you could access the wider array of DeFi products that were moving to the chain. In 2024, building on Solana means you can access users who are exploring meme assets. Or on Base, you could access consumer products.

Currently, versions of this are appearing when founders launch an AVS on EigenLayer. Big brands with operational expertise fuel growth when incentives are aligned.

Flying under a larger flag requires founders to punch above their weight. Large protocols (or brands) don't need to work with startups unless they can out-execute and meet consumer needs. It's the small, efficient teams that beat death by committee at large firms. If you are a founder building for larger flags, consider having ready proofs of concept or bodies of work (like research) to support your claims.

One way SuperGaming did this was through focusing on their core strengths. By 2014, the team had five years of experience building iOS apps and cloud server development experiences for over a decade. Instead of hopping on the hot new trend, they built multiplayer games for iPhone on 3G networks.

People were not thinking about mobile as the next big multiplayer gaming medium, but that’s where the team’s focus was. When they spoke to large enterprises, this unique wedge helped sway decisions.

Most decision-makers can be swayed by time saved if you have a ready body of work in such situations. You can, however, be killed writing proposals and navigating mazes of internal bureaucracies playing this game. The nuance here is that June Software did not find users just because they were collaborating with a large name. You can BD your way into some of these collaborations. They had also built a product users loved along with it.

A great product with mediocre distribution can work, but a subpar product with great distribution won't. For operators, the challenge is finding the middle ground.

In July 2013, Hasbro acquired 70% of Backflip Studios for $112 million. Hasbro, interestingly, owns the intellectual property (IP) rights to Nerf guns. Roby and his team quickly scrambled to make a Call of Duty-type game for Nerf guns using those same IP rights. The plan for Nerf gun based shooters itself got scrapped a while later. But it set stage for the next chapter in their story.

Identity

Work on an early build of MaskGun began in 2015. By 2022, the game had close to 60 million downloads. That success did not happen overnight.

Smartphones were less powerful during early iterations of MaskGun. The oldest phone that could run it was an iPhone 3GS, with a latency of 350 milliseconds (ms). Roby and his six-member team settled on naming the game MaskGun because they did not have a 3D animator on the team. If the characters wear masks, they need not worry about emoting the characters. Talking about being scrappy, but effective.

It took two years to gradually iterate the product to a point where it had more adoption. Back then, using Facebook's sign-up flow allowed a developer to see the user's handle on the social media platform. Roby would engage with his most active Facebook users at the time, establishing lines of conversation that would help him understand how or why they were spending time playing MaskGun.

He would directly speak to thousands of users to understand why they were in his game for tens of hours each day. In turn, they would share their own stories.

Some of the stories were quite moving. For instance, when one of Roby's gamers reached out with the sad news of an amputation, he moved quickly to implement a skin in the game that highlighted the person. The conversation with the user initially started with an interest in adding MaskGun stickers to their prosthetic leg.

Roby made sure the user felt seen and heard within the product.

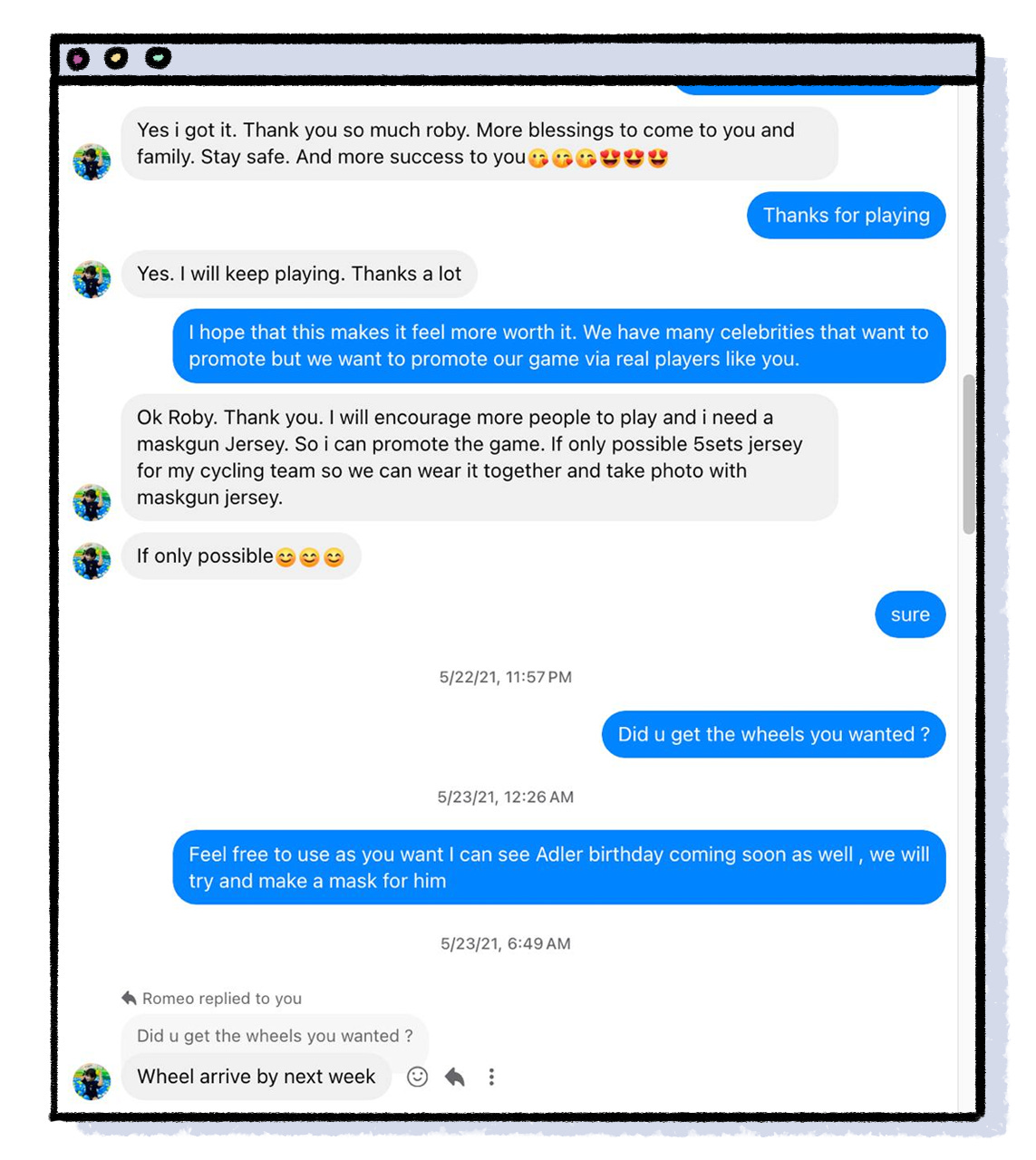

In another instance, he reached out to a gamer who had spent five years on his product and spent over $2000 within the game. Roby wanted to sponsor his favourite cycle. These are usually unknown names—not the kind of people a marketing manager would think about incentivising in any form. But Roby's focus was not on reach or distribution.

It was on building relationships with the people who spent the most time in his game.

When I was in Roby's office, he showed me his Facebook account. He had nearly a decade of DMs from users asking him for quick bug fixes. Or to level down their accounts within his games. Or updating him about life events. One of the users even made Roby the legal godfather of his child. These things don't happen because a marketing manager spends dollars on distribution.

These things happen because a founder is close to the customer. What would lead to better products? Conversations with the best VCs or hundreds of users that spend time with your product?

This choice is reflected in products in unique ways. At the time, when MaskGun was releasing weekly updates, Roby created in-game characters that depicted his most active users in some form. He'd had an 'aha' moment when a user reached out at three in the morning, asking for custom skins for the guns of gamers in his community. That player turned out to be part of a gang in Australia, and he wanted to signal his identity within the game.

Users were adding clan names to their characters in the product and soon wanted to express themselves through the clothing of the characters representing them in the game. These kinds of requests led to the creation of an in-game marketplace.

This need for self-expression is not unique to games. Usually, the products we spend the most time on are the ones that allow us to express our most authentic selves. Reddit, Instagram, and YouTube – all tap into the human need to be seen and heard. Products like games cannot easily replicate the audience base these social networks have. But whenever large enough user bases aggregate, people want to differentiate or rank themselves.

You can use elements of identity in three distinct forms while developing a product.

Talk to your users to make them feel seen and heard. Invest in better outcomes for them. This will help create a critical mass of users.

Provide avenues for self-expression so that they can interact with the product in a way that ties to their unique identity.

When there are enough aggregate users, give them a ranking mechanism for social status and clout.

Our worlds may have gone digital, but humans remain social animals, and our need to be seen, acknowledged and ranked persists even as times change.

How does this translate within Web3? You can observe it with how Dune emphasises on empowering their users. They have a wizards section which makes sure to highlight their most active users. Similarly, Layer3 has a leaderboard where users compete to maintain the highest score for using their product. People develop a sense of belonging when they are highlighted through a product, which, in turn, works wonders for retaining them.

This works with developers too. Dan Romero famously used to schedule back-to-back 15-minute calls with developers interested in coming to Farcaster. Those conversations make onboarding to a primitive protocol more personal.

Naturally, these things don't scale. At a billion users, products become more impersonal. But a different element keeps users together. That is culture.

Culture

By 2022, MaskGun had close to 60 million users. It had been in production for close to eight years, but something was still missing. Between PUBG and Fortnite, the market for shooters had massively evolved. By Roby's own admission, the product could have gone farther in terms of user growth.

A year prior, Roby and a small team of 4 people began talking to users near their office. Over six months, they would meticulously take notes from 1000 users. College students, people heading home from work, gamers – it was a complete mix. Through these conversations, they would capture the psyche of who they were building for.

A blank canvas was in place, and art had to be made.

The dots to make the art came from these conversations.

What quickly became apparent was that even though India was a huge gaming market, there was very little representation of its users within these games.

In MaskGun, Roby noted how self-expression helps build a sense of belonging. In NinJump, he noted the power of IP in bringing people together. For the next chapter, he would combine these ideas, and thus was born Indus – their flagship game. It is still in early beta, so I will avoid mentioning why Indus itself is unique. Or why it is the next big game.

What interested me is that Roby began thinking about his product through the lens of IP and self-expression. Blend the two, long enough, and you have culture.

Culture is the shared beliefs we hold and forms of expression we use as a society. It does not account for the individual. It looks at what we do as a collective.

There's a limit when you text tens of thousands of users individually to onboard them. But distil it into culture, and you have a system that scales. Apple was transitioning into culture when it ran this ad in 1984, arguing for the viewer to fight against Big Brother, or this ad, where they asked viewers to think differently.

One of my favourite instances of a product becoming a culture is that of sneakers. Think of them from the perspective of what they do. All shoes serve the same function; they are cushions for your legs. But add to them two decades of manufacturing desire, tie in stories of an athlete's greatness and encourage a parallel market, and all of a sudden, you have sneaker culture. The product transcends the function it serves.

But how do you do this if you don’t have decades to spend on building culture? You (try to) make it with representation and lore.

Indus' current approach to building culture is through the representation of characters and content from India within the game. It can be a double-edged sword. Shallow gameplay, with representation alone, may not work. But building myth and lore that people can believe in gives space for imagination about how users perceive a product. Long before they set out to build the game, the team sat down and thought about what Indo-futurism could look like.

A futuristic vision for India is represented through the game as a medium. Characters in the game are an ode to multiple mythological characters gamers may have grown up hearing about from their childhoods.

They then combined it with several creator programmes to onboard the community. In the early stages, most founders build in public, alone. Onboarding a network of creators to use the product and publicly critique it amounts to building the game in public. In fact, the firm routinely hires its best creators to join their team at their offices. Indus also routinely conducts offline events in smaller towns in India, market segments that do not prioritise gaming.

When a brand goes to markets with underserved niches, the brand builds permanent loyalty. This strategy helps create distribution while gathering critical feedback from users. Naturally, some feedback will be negative. This one, for instance, is a critique of the game's current deficiencies.

When you are building a community, you open yourself up for both criticism and adoration. A healthy community is one that pays heed to both.

Indus currently works with many of the region’s largest creators. In fact, Techno Gamerz - one of the largest YouTubers in the region was a character in their game. Instead of doing one-time media buys, the studio focuses on lasting relationships.

Web3 products try to build culture through branding. Our conferences permeate Twitter algorithms to allow for real-life interactions. But we rarely recognise a brand for its culture. The closest we have is likely Berachain, who gets a tremendous amount of heat for the noise they produce. During Token2049 in Dubai, they ran a whole drone-show and ran ads on cabs.

And yet, when I consider it from the perspective of a game trying to make its mark, I begin to see their strategy.

Creators (or researchers) rarely have an inside look at how products are built. Consequently, the working teams experience fragmented feedback loops and creators' incentives suffer. Something that is becoming increasingly apparent within Web3 is that paid engagement with creators only happens when financial incentives are involved.

That is, the people who are engaged are expected to paint products (or protocols) in a good light. For us to evolve, sponsorships will require room for considerably more candour. Too often, creators left alone, produce something far better than what most marketing managers can scramble to put together. But we are not there as an industry yet.

Digitising Third Places

While writing this story, I realised that the metaverse is not some distant concept for the future. It is here. In the games we play and the platforms we spend time on. Twitter is a third place. So is Telegram. Maybe even Uber eats is for some. But not all of them replace the third places we used to spend time at in the past or serve the functions they once used to.

A major cause of rising depression is the absence of third places. Historically, the village square, cafe or playgrounds used to be where we spent our time. As interactions go online, we need new town squares. Games increasingly fill that void. Many of Super's users use its IP for self-expression and identity.

In an analogue world, people use religion and politics as mechanisms of identity. In a digital world, we will use our online representations and the worlds we spend time in as extensions of our identity.

How can founders tap into this? A lot of it boils down to four core components:

Building sufficient distribution through collaborating with known names. If you are a small startup, working with brands (or creators) that are exceptionally well-positioned in the niche you are targeting is the way to go.

Making users feel seen and heard gives mechanisms for capturing feedback on shorter feedback cycles.

Creating culture by following a set of values and having products reflect this

People no longer buy the product. They buy the story and the people who associate with the product. In 2021, part of the reason Bored Apes became hot was the number of celebrities endorsing it. In owning a Bored Ape, you could signal that you owned the same asset Jay Z owned. In 2024, owning a Bored Ape is a sign of being in great distress, given where the price is.

To nurture and distribute stories, you need community. And you cannot do that inorganically overnight. For Roby, that process was a decade long. For some of the protocols we've worked with, that process took 3–4 years on average.

Strong communities require good products that act as a unifier. The kind that users will miss if its taken down. Think about how we scramble whenever Twitter or Whatsapp goes down.

Some games in SuperGaming's catalogue were maintained because 20 users were still playing them years after an update was last released for them. Be it with NinJump in 2014 or MaskGun in 2022, Super's focus was on good products that were iterated upon. In our observation, good products create engaged communities.

When leveraged properly, it helps create flywheels that retain users longer whilst giving teams competitive advantages on how they build. MaskGun grew organically to 90 million players as of writing. Indus has 12 million pre-registrations. The former has not had any game updates in a year now, but sees 50k new users coming in each day. That, is the edge building healthy communities give.

Ultimately, investing in communities and curating vibes is not simply about pleasing people. It is about investing in user retention and consumer feedback in mechanisms that are organic, real and true to the brand. When Roby built communities in the early 2010s, it was with the intention of getting organic word-of-mouth distribution for his product. Over the decade, he realised that a healthy community is one that facilitates user to user interaction.

People come for the product but stay for who else is using it. The culture a product pushes determines how users treat one another. This is why we see very different user behaviour across platforms. Be it 4chan, TikTok or Instagram. Latent culture defines communities. Part of a founder’s job, is fostering the culture towards where it needs to be.

We are all building worlds through the products we build. Communities make these worlds inhabitable and a little less lonely for the residents who come around.

Surviving the heat in Dubai,

Joel

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

- Podcast Episode: Ivangbi from LobsterDAO

Damnnn this is so good! Thanks!

cool, thanks

what about gaming and meta in new cycle?

I mean Decentraland, and SandBox if they have a chance make hype again?