Aggregating Liquidity

The distribution vs supply argument

Hello!

Every morning, I wake up and rush to the café downstairs. I grab my usual coffee, then head to the grocery store, like any self-respecting modern-day hunter, to pick up my protein and fibre for the day. Sometimes I look for red dragon fruits.

Last week, I found myself wondering what part of the supply chain makes the most money—the store-front or the producer?

The question may seem non-consequential, but much of what we know about aggregation theory revolves around that theme. What do you optimise to own in an emerging market—the store front, or the supply chain? Saurabh has been exploring the answer to this question over the past week and today’s story is what has come of it. We break down how Jupiter’s approach to M&A and market expansion contrasts with Hyperliquid’s, and try to answer the ancient question that riddles all market participants. Where does value ultimately accrue?

As always, if you are building a new market, reach out to venture@decentralised.co. We’d like to talk.

Special thanks to Jupiter’s Kash for explaining their stack on a Sunday.

On to the issue..

Joel

Hello friends,

In November 2023, private equity company Blackstone acquired a pet care app called Rover. Rover started as a simple way to find someone to walk your dog or watch your cat. Pet care has long been fragmented. Tens of thousands of small, mostly local and offline providers. Rover aggregated that supply into one searchable marketplace, added reviews and payments, and made it the default place for pet care services. By the time Blackstone took it private in 2024, Rover had become the choke point for demand in its category. Pet owners went to Rover first, and providers had little choice but to list there.

ZipRecruiter did something similar for jobs. It pulled in listings from employers, job boards, and applicant tracking systems, and pushed them out across multiple channels. They posted jobs on social networks like Facebook based on a simple insight: people who are not really looking for a job are usually the more desirable candidates. For employers, ZipRecruiter became a one-stop distribution pipe; for job seekers, it was a single front door to a scattered landscape. It didn’t own the companies or the roles, just the relationship with both sides. Once that relationship was entrenched, ZipRecruiter could charge for visibility and placement. This is aggregation economics 101.

Aswath Damodaran calls this model “owning the shelf”: pull together messy, fragmented supply, control how it’s displayed, and charge for access. Ben Thompson calls it Aggregation Theory: build a direct relationship with the end user, let suppliers compete to serve them, and skim value at every transaction. The defining features are the same across categories—Google with web pages, Airbnb with rooms, and Amazon with products.

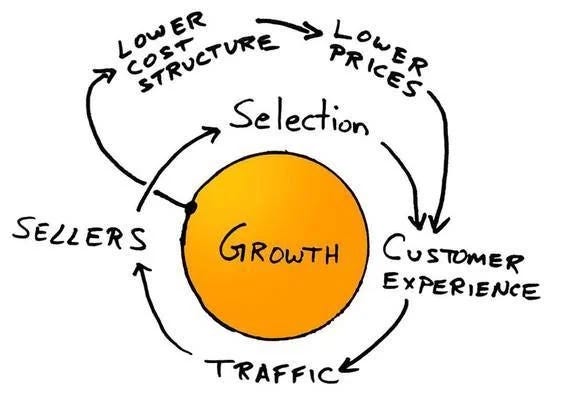

The Amazon flywheel is the canonical sketch of this idea. In the post-dot-com-bust doldrums, Jeff Bezos and his team workshopped Jim Collins’s “flywheel” concept and drew a loop that every MBA can now reproduce from memory. More selection leads to a better customer experience, which brings in more traffic, which attracts more sellers, which lowers the unit cost structure, which allows for lower prices, which, in turn, brings in more selection. Turn it once and not much happens; turn it a thousand times and the machine starts to hum. Bezos’s house slogan for this era was “Your margin is my opportunity.” The whole point is self-reinforcement. More users, more suppliers, lower costs, and eventually higher profits, all compounding in the same direction.

It’s a beautiful model when it works. The costs don’t scale the same way the revenue does, and the product gets better as more people use it. But as Damodaran warns, it only works when two things hold true. What you’re aggregating is valuable, and the people providing it can’t easily walk away. Without both, your moat is shallow. Think of eBay in the early 2000s. It aggregated millions of quirky, one-off sellers and the buyers who wanted their Beanie Babies or vintage Pez dispensers. That aggregation was valuable. But once sellers realised they could set up their own Shopify stores or list on Amazon, which was happy to ship faster and take thinner margins, they walked away. The flywheel doesn’t stop overnight, but without a captive supply, it starts to wobble. And eventually it becomes just a regular wheel—the kind anyone can roll.

Damodaran explains the power of platforms and aggregators in a refreshingly physical way. He talks about “controlling the shelf.” Not literally the planks in a grocery aisle, but the place where customers first look when they want something. If you control that space, you get to decide what’s on it, how it’s displayed, and what it costs to be there. You don’t need to own the goods themselves; you own the relationship with the buyer, and everyone else has to come to you to get in front of them. In his write-ups of companies like Instacart, Uber, Airbnb, or Zomato, Damodaran returns to the central point. The job of an aggregator is to take a messy, fragmented market, put it behind one glass pane, and make that glass pane the only window worth looking through. Once you’ve done that, you can charge for access to the view.

Ben Thompson thinks an aggregator is a business that builds a direct relationship with end users at internet scale, delivers them a standardised, reliable experience, and then lets suppliers compete for the privilege of serving them. At internet scale, you’re not talking about the biggest store in town, but about being the store for every town, all at once.

The marginal cost of serving the next customer is effectively zero, and yet the marginal value of having them is enormous. Because each one reinforces your brand, your data, and your network effects. And because the aggregator owns the demand, suppliers become interchangeable. That doesn’t mean there’s no variation in quality; it means the supplier can’t take the customer relationship with them if and when they leave. The hotel on Expedia, the driver on Uber, the seller on Amazon, they all need the aggregator more than the aggregator needs them.

Damodaran’s writing, across industries, is a reminder that this wheel doesn’t spin the same way in every market. Uber, for example, aggregates local driver liquidity, but drivers can keep three apps open at once and take whichever ping comes first. It makes the moat leaky. Airbnb’s hosts, on the other hand, are selling unique properties with limited alternative channels, making their take-rate much more durable.

In thin-margin sectors like grocery delivery, the shelf might be valuable, but there’s only so much you can skim before suppliers push back, which is why Instacart had to move into advertising and white-label logistics to grow.

The underlying economic fabric of the supply matters just as much as the number of people looking through your window. What I mean by that is, if what’s inside is a commodity that can be picked up next door, you’re just running a convenience store with a better view. But if what’s inside is scarce, differentiated, and hard to find elsewhere, then people will keep coming to your window, even if you charge a little more for the privilege. Think high-end stays on Airbnb.

Why Aggregators Fail

When the right conditions are missing, an aggregator ceases to be a flywheel. It is just a merry-go-round that costs a lot to run.

Quibi is a textbook example of what happens when you don’t control the shelf. The platform had expensive Hollywood shows and a sleek app, but no direct line to the customer. The people who might’ve watched Quibi were already on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok. Those platforms owned the starting point of attention. Quibi, by contrast, locked its content inside its own app, far from where audiences already were.. That meant it had to buy every user with ads and promotions.

As Ben Thompson has pointed out, good aggregators begin with a zero-marginal-cost way to reach users, through built-in distribution, an installed base or a daily habit. Quibi had none of that. It ran out of time and money before it could build it.

Facebook’s Instant Articles had a similar problem. The idea was to pull stories from many publishers, make them load faster inside Facebook, and monetise that traffic. But publishers could easily put their stories elsewhere. They were already on the open web, in apps and on other social feeds. Instant Articles was never the default reading experience. It was just one option in a busy news feed. Without exclusivity or habit, it did not make Facebook more powerful or publishers more dependent.

In both cases, the same rules were broken. Neither company owned the user relationship in a way that created default behaviour. And they didn’t have a supply base that would be meaningfully worse off if it walked away.

Thompson’s checklist for a good aggregator is simple.

You connect directly to users and own that relationship.

You have supply that is either unique or interchangeable enough to be replaceable, making it impossible for a single supplier to hold you hostage.

Your marginal cost of adding more supply is close to zero or low enough, so your business model improves as you grow.

If those boxes are not ticked, you are not an aggregator. You are just another middleman, easy to swap out when the next one comes along.

When Liquidity Becomes a Moat

Projects can have different moats within the crypto industry. Some projects build a brand by having licenses and regulations in place. USDC commands trust because of its transparency and regulatory posture. Others rely on technology. Starkware’s proving system or Solana’s parallel execution fall into this category. Some lean on community and network effects. Farcaster’s active user graph is an example. But the one that shows up most often among the winners, and is the hardest to dislodge when done right, is liquidity.

And the “when done right” really does matter. Liquidity will walk if the incentives to move are strong enough. In 2020, Sushiswap’s “vampire attack” drained over a billion dollars from Uniswap in mere days by offering liquidity mining rewards. The lesson is simple. Liquidity sticks only when leaving is more painful than staying.

I have written about how Hyperliquid understood that. It built the deepest DEX order books for its own perpetual exchange. But went beyond it. It lets other apps and wallets tap into that liquidity directly. Phantom could plug into Hyperliquid’s order flow and give users tight spreads without having to build its own markets. In that setup, the aggregator needed the supplier more than the supplier needed the aggregator. Once traders and applications start routing through you by default, you’re not just another venue. You’re the venue they can’t avoid.

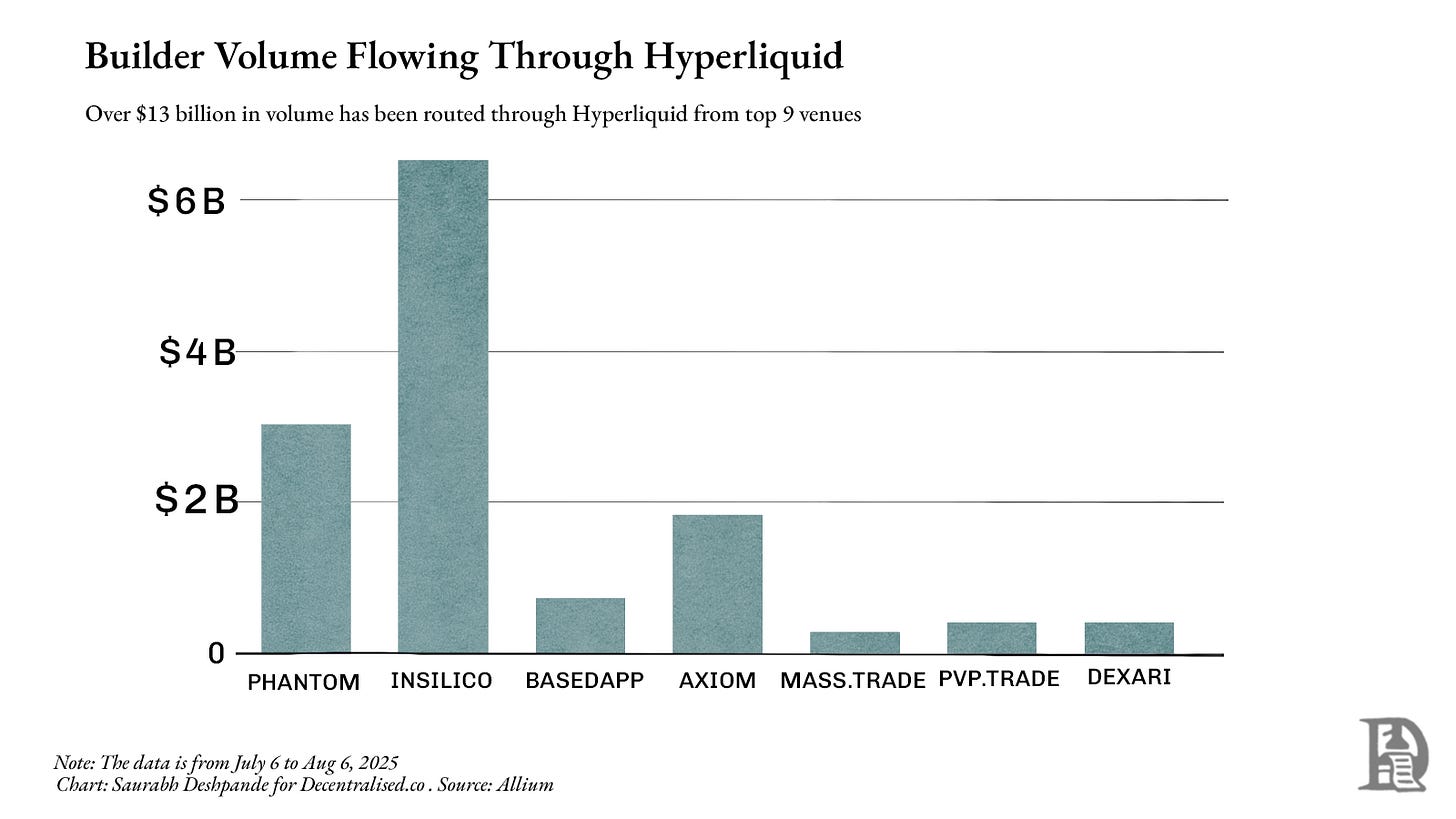

In addition to Hyperliquid’s own venue, over $13 billion in volume has flown through it from other builders over the last month. Phantom has earned over $1.5 million by routing $3 billion in volume through Hyperliquid. This shows how powerful Hyperliquid’s network effects are at the moment.

Liquidity is what lets you turn one asset into another without the price moving against you. In finance and in DeFi, deep liquidity makes trading cheaper, lending safer, and derivatives possible. Without it, even the cleverest protocol becomes a ghost town. Once in place, it tends to stay. Traders and apps route to wherever the deepest pools are, which brings in more liquidity, which tightens spreads, and attracts more trading.

That is why protocols like Aave have kept their positions for years. Aave holds large lending pools across many assets, making it the default choice for borrowers and lenders who want size and safety. As of Aug 6, Aave has more than $24 bn in TVL across different chains. In the last 12 months, borrowers paid $640 million in fees, and the platform earned ~$110 million in revenue.

The same dynamic explains how Jupiter, a Solana-based aggregator, moved from being a routing tool to the default entry point for trading on the network. On Ethereum, Uniswap had already concentrated most spot liquidity, so an aggregator like 1inch could only offer marginal improvements. On Solana, liquidity was split across Orca, Raydium, Serum, and smaller venues. Jupiter combined them into a single routing layer that consistently delivered the best prices. At one point, it was responsible for roughly half of Solana’s total compute usage, so any slowdown or outage would immediately affect execution quality across the network.

Once you see liquidity as the thing being aggregated, Jupiter’s product decisions are easier to understand. The acquisitions, the mobile app, and the expansion into new trading and lending products are ways to capture more order flow and keep liquidity routed through Jupiter, reinforcing the position it built.

Jupiter is worth focusing on because it is one of the clearest examples in DeFi of an aggregator climbing the ladder from a niche tool to a platform for liquidity. What started with simply finding the best spot pieces turned into the default route for liquidity on Solana. From there, Jupiter expanded into new products that attract entirely different kinds of liquidity. Watching how it moved through these stages and how it used each of them to reinforce the next offers a live case study of the aggregation dynamics Ben Thompson and Aswath Damodaran describe.

The Levels of Aggregation

Ben Thompson’s three questions are a good cheat sheet for spotting an aggregator in the making.

1. What is the critical differentiator for incumbents, and can it be digitised? In DeFi, the differentiator is liquidity. Whoever has the deepest pools can offer the tightest spreads and the safest loans. Liquidity is already digital, so it’s trivial to read it, compare it, and route between it.

2. If that differentiator is digitised, does competition shift to user experience? Once anyone can plug into liquidity, the battle is about execution quality: faster settlement, better routing, fewer failed transactions. That’s where products like BasedApp and Lootbase come in. BasedApp wraps DeFi primitives into a smooth, mobile-native experience that simplifies complexity for casual users. Lootbase, on the other hand, brings Hyperliquid's deep perp liquidity to mobile—making it easy to trade perps on the go, with low latency and without losing access to the full power of Hyperliquid’s backend. Both reflect the same idea: once liquidity is open and digitised, UX becomes the wedge.

3. If you win the user experience, can you build a virtuous cycle? Traders come to you for better prices, which attracts more liquidity, which makes the prices even better. Liquidity is sticky when it’s embedded in habits and integrations.

Be the place where the market starts. If suppliers can’t afford not to be on your shelf, you can charge for placement or in DeFi’s case, decide the flow of orders.

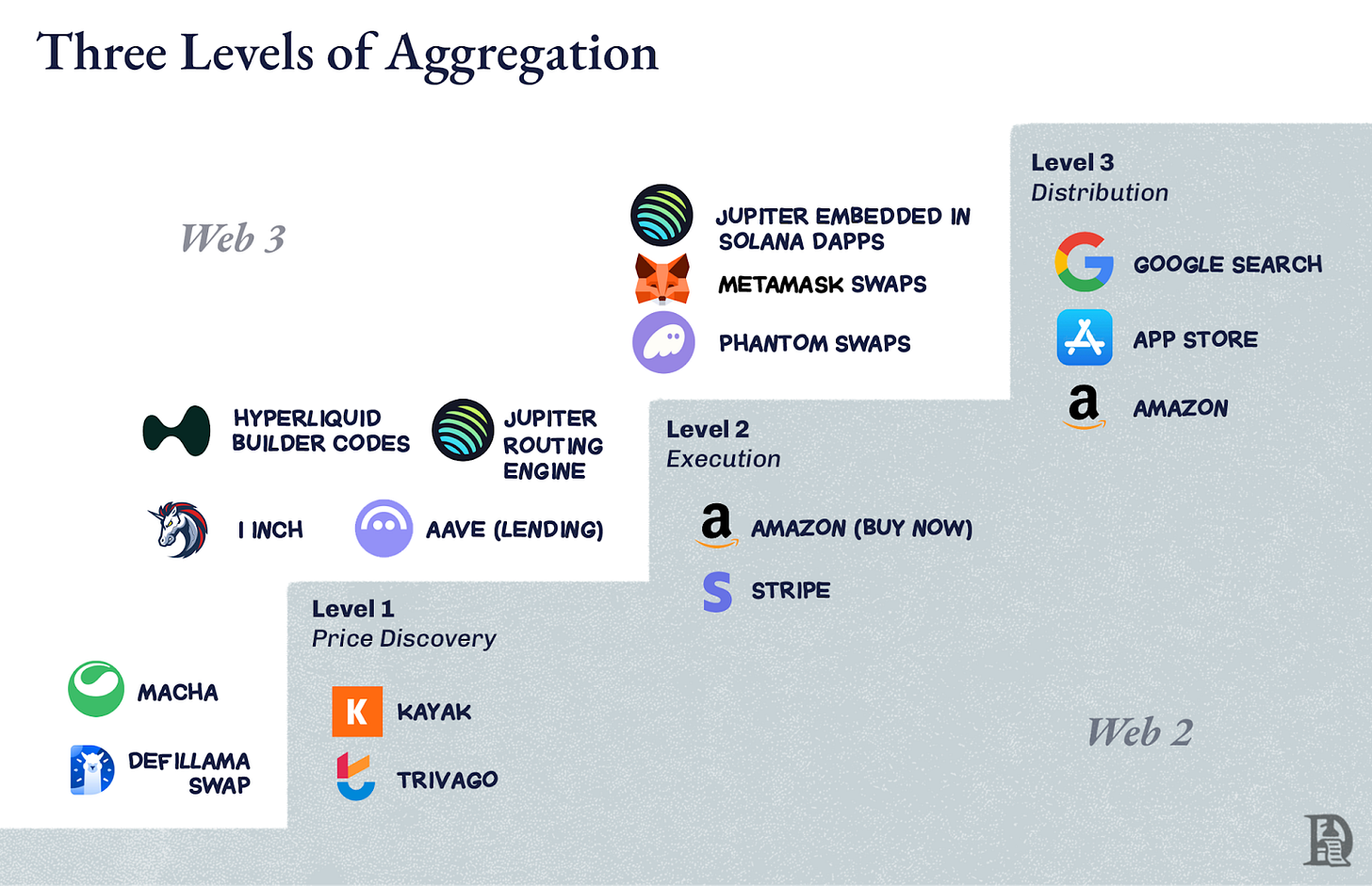

Level One: Price Discovery

This is the simplest job: tell people where the best deal is. Kayak does this for flights. Trivago does it for hotels. In crypto, early DEX aggregators like 1inch or Matcha lived here. They scanned the available pools, showed the best rate, and let you click through. Price discovery is useful, but fragile. DeFiLlama’s swap is also the same. It scans through different aggregators and native AMMs and gives you options.

If the underlying market is already concentrated, like Ethereum spot trading on Uniswap, the improvement from routing is small, and users can just go straight to the venue. You are helping, but you are not essential.

Level Two: Execution

Here, you stop sending people somewhere else. You do the thing for them. Amazon’s “Buy Now” button is a level-two move. It finds the cheapest option and processes the purchase with your saved details. In DeFi, Aave is here for lending. When you borrow, the liquidity is already sitting in its contracts. Execution adds stickiness because you are now part of the outcome. The good experience of fast settlement, no failed trades, is tied to you. Not to the abstract market.

Level Three: Distribution Control

This is where you become the starting point. Google Search is here for the web. The App Store is here for mobile apps. In crypto, a wallet’s built-in swap tab can be here for casual users: it’s where they start and finish their trades.

For Solana, Jupiter has reached this point. It began as a price-finding tool, moved into execution with smart order routing, and then got embedded into the front ends of Phantom, Drift and many others. A large share of Solana trades are Jupiter trades, even if the end user never types “jup.ag” into a browser. That’s distribution control. The supplier cannot reach the customer without going through you.

Climbing the Ladder in DeFi

The challenge in DeFi is that liquidity can move quickly. Incentives can drain a pool overnight. So, moving from level one to level three is not about simply being the first aggregator; it’s about creating enough reasons for liquidity and order flow to stay routed through you even when others try to replicate it.

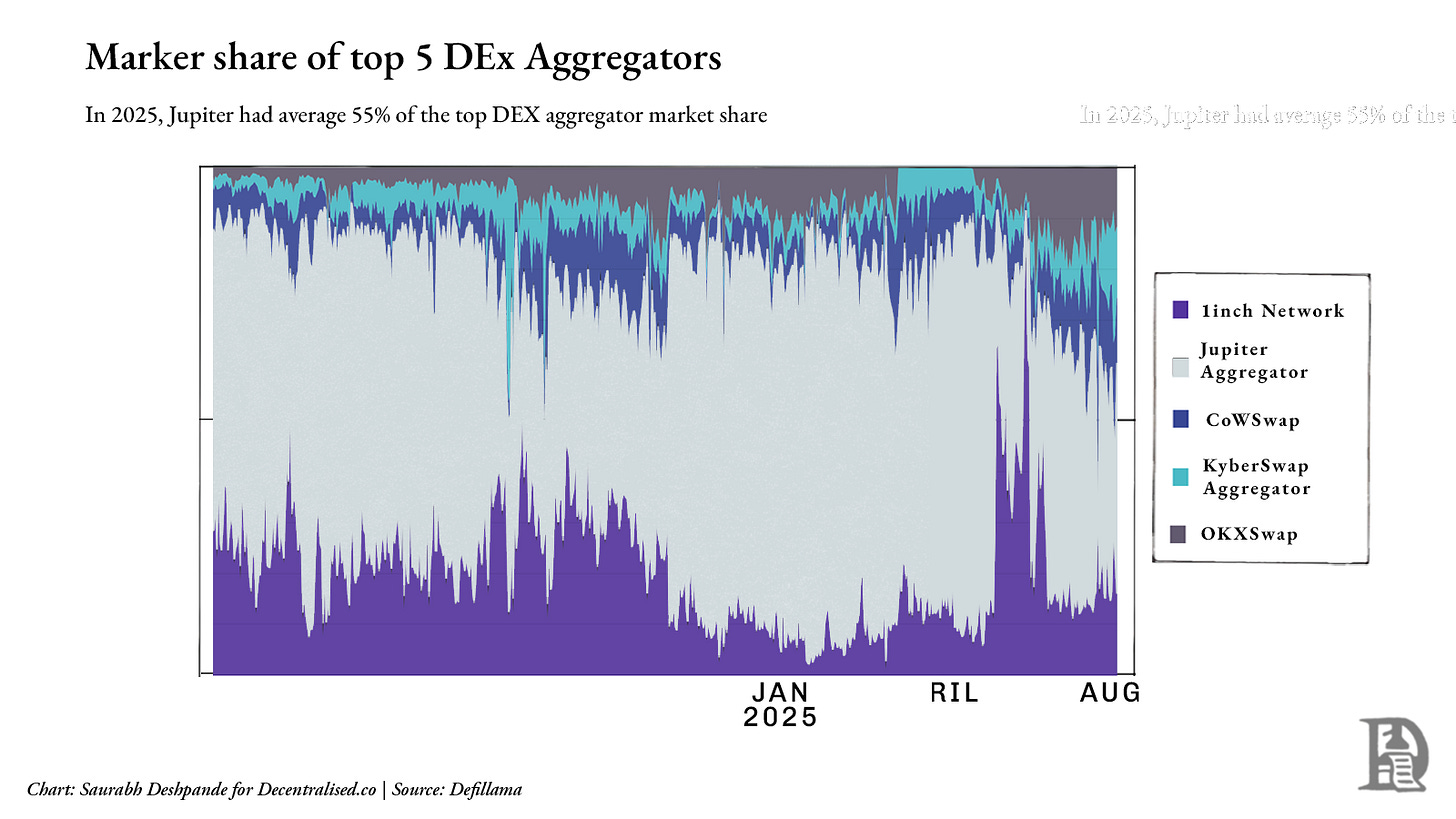

On Ethereum, 1inch stayed mostly at level two because Uniswap had already done the aggregation work by concentrating liquidity. Routing was still useful for edge cases, but the improvement was small enough that many traders skipped it. Plus, there are other aggregators like CowSwap and KyberSwap that have a meaningful market share. Aave is level two because they own the execution for their niche. It is the infrastructure, rather than just a starting point.

Jupiter’s advantage on Solana was that it could climb all three levels in sequence. Liquidity was scattered, so level one had real value. Its routing engine gave better execution than manual swaps, so level two was a natural step. And by integrating directly into wallets and dApps, it reached level three. Distribution control over Solana’s liquidity. At one point, roughly half of Solana’s compute usage came from Jupiter transactions for two reasons. The demand side in the form of traders, and the supply side in the form of liquidity pools, both needed Jupiter.

Once you are at level three, the question changes. It’s not “how do we get more users” but “what else can we run through this distribution?” Amazon started with books and ended up selling almost everything. Google started with search and ended up owning maps, email, and cloud computing. For Jupiter, the distribution is order flow. The obvious next step was to add more products like perps, lending, and portfolio tracking that use the same liquidity relationships.

The bigger play here is Jupnet. Solana doesn’t yet match the specialised throughput and execution profile of venues like Hyperliquid, which are engineered from the ground up for finance-grade latency and determinism. Those qualities are essential to scaling a full financial stack to real-world volumes. The easier option would have been to launch these products on a chain where those guarantees already exist. Instead, Jupiter is taking the harder route by building Jupnet as an app-controlled, low-latency execution layer designed to run alongside Solana.

The intent is for Jupnet to serve as shared infrastructure within the Solana ecosystem. It will be a layer where perps, RFQ systems, batch auctions, and other latency-sensitive flows can execute with precision before settling natively to Solana. If successful, it will keep users and assets on Solana while delivering the kind of speed and determinism expected from vertically integrated venues. This is an attempt to close the gap between general-purpose blockchain throughput and the micro-latency demands of global finance, without fragmenting liquidity across chains.

But it’s important to zoom out. While Jupiter may be dominant within Solana, it still faces stiff competition at the industry level. On a broader cross-chain basis, 1inch, CoWSwap, and OKX Swap remain meaningful competitors. As of 2025, Jupiter has averaged around 55% of the market share among the top five DEX aggregators, but that figure fluctuates based on chain activity and integrations. The chart below shows just how fragmented the aggregation layer still is outside Solana.

At this point, it’s clear that Jupiter is the aggregator in the Solana ecosystem. The flywheel has started. More traders mean more liquidity, more liquidity means better execution, and better execution means more traders. At that point, you are not just a liquidity aggregator. You are the shelf. The habit. The place where the market begins. But staying there is not guaranteed. So, how do you grow from here, especially when liquidity is no longer enough? Jupiter’s answer is to acquire founders who already command new kinds of user flow, and route it through itself.

M&A as a Growth Engine

A couple of months ago, I wrote about two themes that are fundamental to how companies scale. The nature of compounding innovation and the way businesses use mergers and acquisitions to accelerate that compounding. The first is about building on existing advantages so that each new product, feature, or capability benefits from everything that came before. The second is about recognising when the fastest way to add those advantages is to buy and not build.

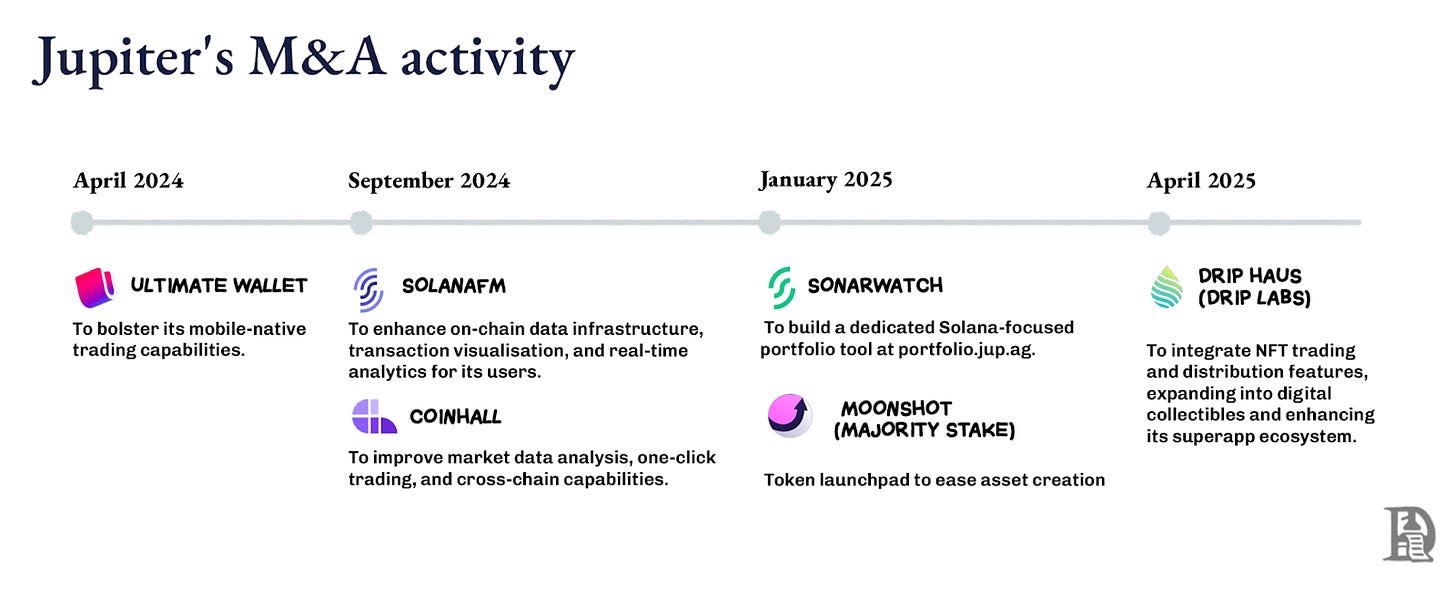

Jupiter’s evolution has traces of both. Its approach to M&A is rooted in finding founder-led teams with real traction and folding them into a distribution network that magnifies their impact. The company looks for teams with deep expertise in their verticals, enabling Jupiter to expand its surface area without slowing the core roadmap.

This approach is more than buying features to bolt on. It’s about finding teams that already dominate a slice of the market that Jupiter wants to reach. When those teams are plugged into Jupiter’s distribution wallet surfaces, API, and routing, their products grow faster, and the flow they generate feeds back into Jupiter’s core.

Moonshot brought a token launchpad for projects raising liquidity, turning new token creation into direct swap and trading activity on Jupiter. DRiP added a community-driven NFT minting and distribution platform, capturing attention from audiences far from trading UIs and turning it into on-chain actions. The Portfolio acquisition gave Jupiter a toolset for active DeFi users to manage positions, reinforcing daily engagement. Jupiter could have built these features internally at a much lower cost, but it was about acquiring founders and not just features.

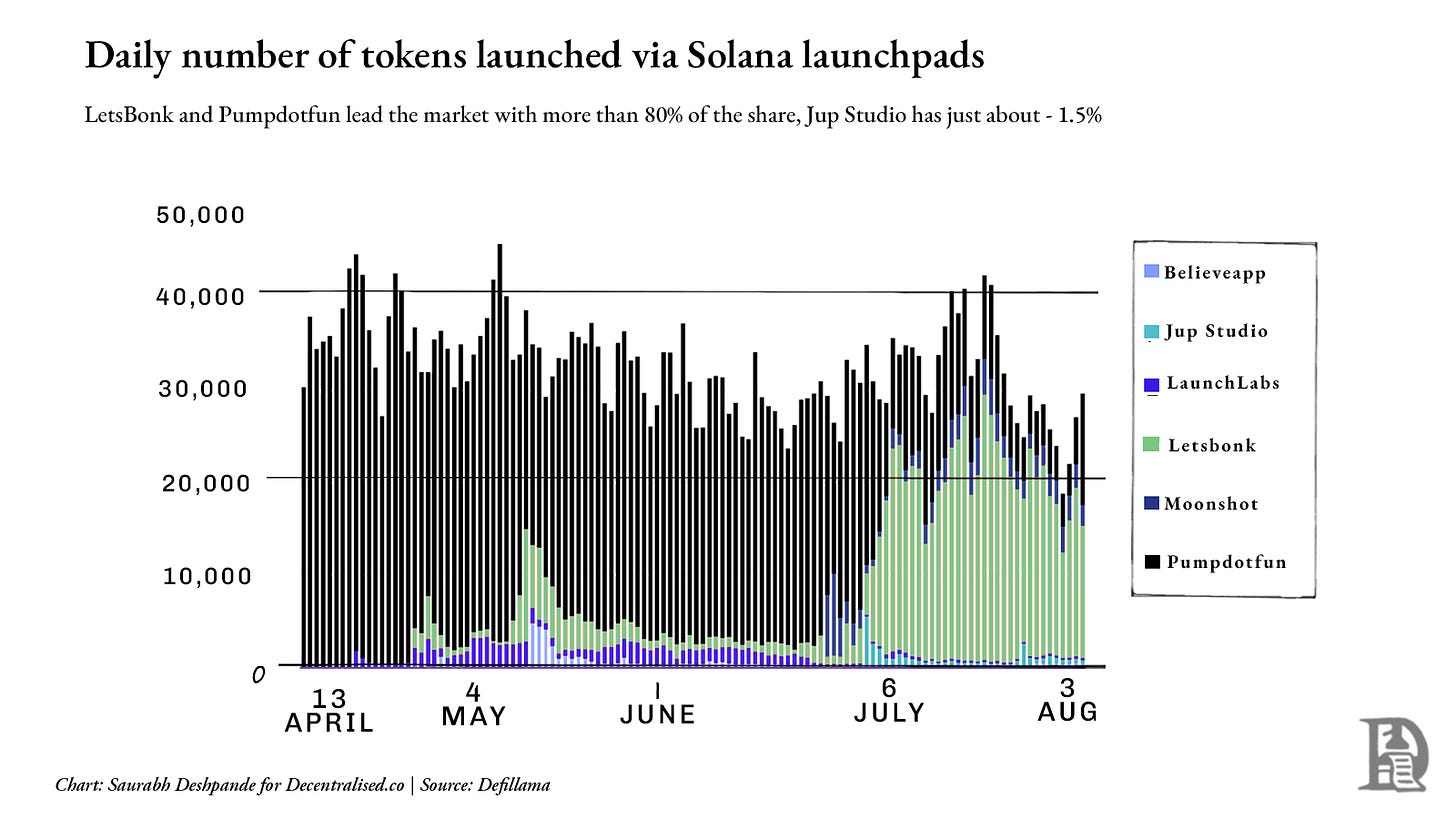

But the growth on some of these metrics is yet to kick in. Take the launchpad segment for example. Market leaders Pumpdotfun and LetsBonk control more than 80% of daily token launches, while Jup Studio and Moonshot together account for less than 10% of the market. The chart below shows how dominant the incumbents remain. In this case, the default may already be entrenched, and Jupiter might have to take a very different approach if it wants to dislodge it.

Founder‑Led M&A as a Force Multiplier

Once you control the shelf, widening it is about bringing in operators who already own a segment of the market you want to serve. Jupiter’s filter is whether this team brings a new kind of liquidity or user that strengthens the flywheel. In this sense, it echoes Amazon’s early flywheel logic, where every addition to the catalogue, every new category of product or type of supplier expanded “selection,” which made the customer experience better, which drove more traffic, which in turn drew in still more suppliers.

For Jupiter, each acquisition is like adding a new aisle to that store, broadening the choices and deepening the reasons for both traders and liquidity providers to keep starting their journey with them.

Here, founder energy becomes a wedge. Acquiring teams with strong founder DNA lets Jupiter break into spaces it doesn’t natively understand, like NFT culture with DRiP or mass retail token issuance, without diluting its core focus. Those founders already know their segment, have communities that trust them, and can move quickly. Plugging them into Jupiter’s distribution channels amplifies their reach overnight, while Jupiter gains a new flow of users and liquidity.

The acquisitions illustrate this. Moonshot is a minting and trading funnel aimed at mainstream behaviour, where tokens launched can flow naturally into swaps, funding markets, and perps — all without leaving Jupiter’s ecosystem. DRiP is a creator-first distribution channel for collectables and mints, drawing in communities that would not otherwise interact with a swap interface.

Moonshot added over 250,000 new uses and handled over $1.5 billion in volume in three days when $TRUMP was launched. DRiP has attracted over 2 million collectors with over 200 million collectibles minted and 6 million+ secondary sales.

Integration follows a clear pattern. Founders stay in charge of their product direction. From day one, their products are wired into Jupiter’s interfaces and backend, so they immediately benefit from its user base, and Jupiter benefits from the new flow. Each acquisition adds a distinct liquidity primitive like issuance, culture, and leverage, rather than overlapping with what already exists. The core identity remains intact: all these roads still lead back to Jupiter.

In DeFi, code can be forked overnight. What can’t be copied as easily is where the market begins. Founder-led M&A has let Jupiter add new starting points without losing that central habit, making its flywheel harder to replicate. As app-controlled execution and low-latency infrastructure mature, it’s likely Jupiter will target teams with execution primitives like risk engines, matching layers, and specialised venues, to fold into Jupnet.

Aggregator vs Supplier

Zooming out, it’s clear that two dominant models are now emerging in DeFi: Jupiter and Hyperliquid. Both are powerful, but their strategies couldn’t be more different.

Hyperliquid wants to control the liquidity. It’s not concerned with owning the end-user relationship directly. Instead, it offers liquidity as a service. If you can build a better UX, you’re welcome to use Hyperliquid’s orderbook and execution engine. That’s the idea behind Builder Codes—it allows others to own the front-end experience while Hyperliquid quietly powers the backend. It’s a supplier-first model.

Jupiter, on the other hand, is focused on distribution. It wants to own the surface, the shelf, the starting point. Its strategy is to aggregate fragmented liquidity across many markets by becoming the default interface. It pulls liquidity into itself and then directs it. That means controlling the user relationship, not just the execution rails.

From perps to portfolios, Jupiter is trying to make every financial interface start and end within its orbit.

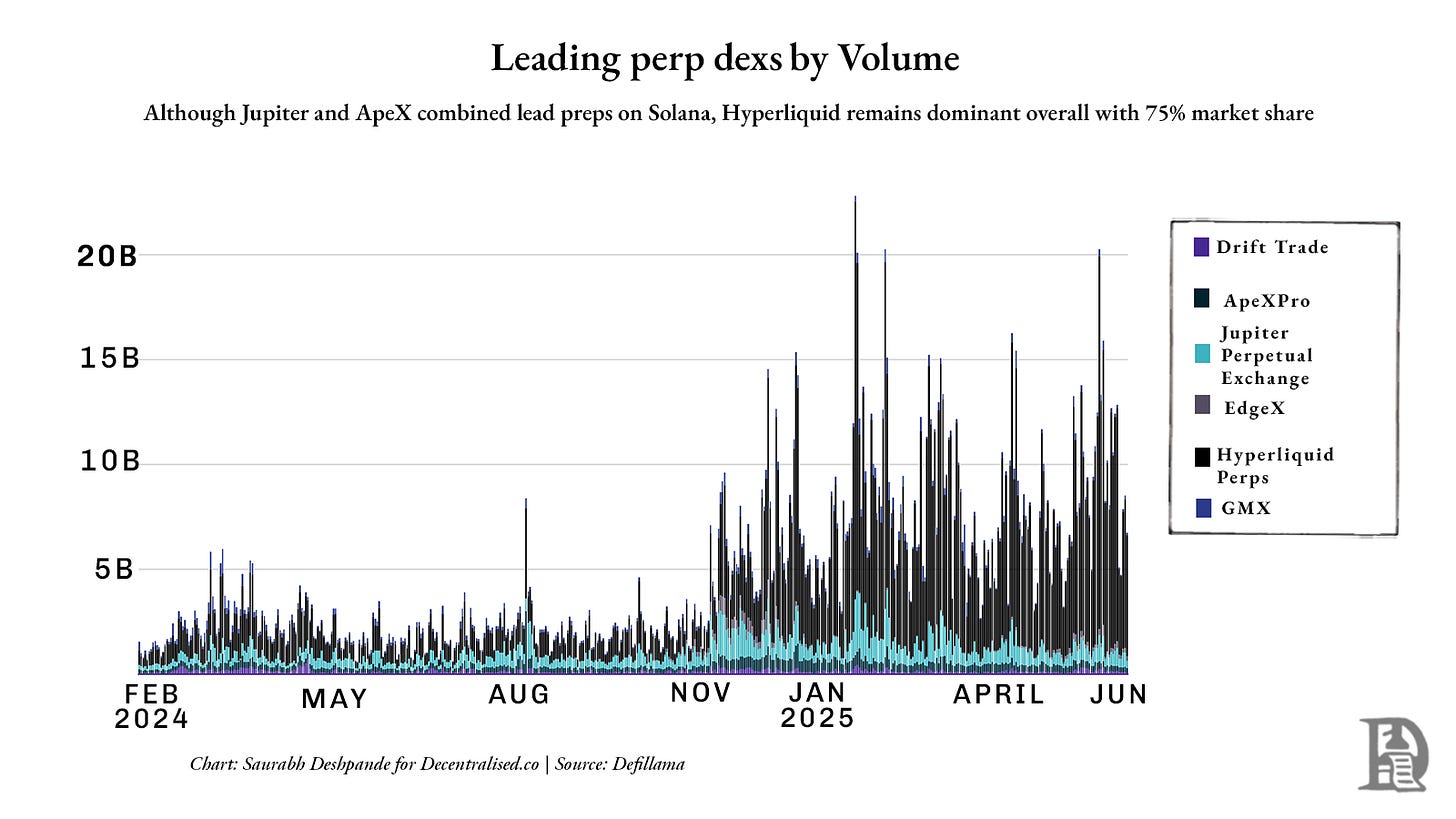

But perps, perhaps more than any other product, reveal the limits of that approach — at least for now. Jupiter has made inroads on Solana, but Hyperliquid still dominates globally, with roughly 75% of the perp DEX market share. The chart below shows how far ahead Hyperliquid is in terms of raw trading volume:

Both models are betting on scale but from opposite ends. Jupiter says liquidity follows user interfaces. Hyperliquid says liquidity is the interface. Jupiter is building the entry points. Hyperliquid is building the endpoint.

And in practice, we’re watching a split play out. If you want a broad surface area and user aggregation, you go to Jupiter. If you want depth, determinism, and composability, you go to Hyperliquid. One turns liquidity into a network of dependencies. The other makes itself the base layer everyone else builds on.

The winner won’t just be who gets there first, but who others can’t afford to leave behind.

And that’s what makes this moment in DeFi exciting. For the first time, we have a real face-off between philosophies. One side says distribution is the moat. The other says liquidity is.

Apps Are The New Platforms

When Ethereum Layer 2s first entered the scene, the hope was that they would serve as the new platforms. Perhaps, as neutral grounds where apps could compose, compete, and scale. But as it turns out, L2s haven’t become platforms in the way we imagined. They’ve mostly remained infrastructure: technical foundations that offer speed, security, and scalability, but stop short of owning the user relationship.

Platforms, by contrast, are interfaces where users start their journey. They are where demand is aggregated, habits are formed, and distribution lives. Few L2s have crossed that line. Most are pipes, not shelves. Few have built meaningful distribution. Fewer still have become the default starting point for users.

Instead, it’s applications like Jupiter and Hyperliquid that are starting to resemble platforms. They own the user relationship, embed themselves in daily habits, and increasingly acquire or plug into other apps to reinforce that position. In fact, they are starting to look a lot like Web2.

Google went beyond just the search engine. It acquired YouTube and turned search dominance into video dominance. Facebook did it by buying Instagram and WhatsApp to expand its grip over attention.

They targeted adjacent categories where they lacked presence but users were already spending time. And crucially, they acquired dominant players in those spaces. YouTube already owned online video; WhatsApp already owned mobile messaging. Once acquired, these apps could immediately plug into Google and Facebook's existing distribution flywheels. The result was a tighter grip on user attention across multiple channels, thereby solidifying their platform dominance.

Jupiter is running a similar playbook. The launchpad, the NFT minting tools, the portfolio manager, and now, Jupnet. They all serve the same purpose: expand surface area, capture more user behaviour, and route more liquidity through themselves. The strategy is to be the shelf, the default, the place where financial interactions begin.

But aggregation isn’t always a guaranteed, winning move. History is full of platform acquisitions and aggregator attempts that failed. Either because they didn’t own the user relationship or because they misunderstood how habits form.

Take Microsoft’s acquisition of Nokia. It was a bet on controlling mobile distribution, but users had already shifted to iOS and Android ecosystems. Microsoft owned the hardware and the software, but its offerings in the form of mobile devices and operating systems were either too similar to what users already had or not compelling enough to force a switch. It didn’t own the app layer, didn’t command developer loyalty, and didn’t offer users a reason to change behaviour. Without control over supply or a clear differentiator, the shelf remained ignored.

Or consider Google’s purchase of Motorola for $12.5 billion. It gave Google control over smartphone manufacturing, but didn’t change how people engaged with Android. Google eventually sold it off to Lenovo just a couple of years later for $2.9 billion. The ownership of supply didn’t translate to control over user demand.

Yahoo’s $1.1 billion acquisition of Tumblr is another case. At its peak, Tumblr was a cultural phenomenon. But Yahoo misunderstood its user base and over-monetised too soon. What looked like a distribution asset turned into a liability when users fled in response to product changes and censorship policies.

Each of these cases reflects a core truth: acquisitions don’t create flywheels on their own. If you don’t own the starting point, if you’re not the habit, the homepage, the interface, users will not follow. No matter how many features you bundle together.

That’s what makes this moment in DeFi so interesting. Jupiter is acquiring front-ends, distribution channels, and liquidity primitives. It’s trying to become the default starting point in Solana’s financial stack. Hyperliquid is doing the inverse: building depth, not breadth, and letting others compose around it.

In a sense, we’re watching the real platform wars play out between apps that behave like platforms. Not between chains, as many expected. And that raises a bigger question: if L2s don’t own distribution, what happens when the apps built on them do? Where does the value accrue? What happens to the FAT protocol thesis?

We’re ending with some unanswered questions, and that’s intentional. Because this isn’t settled. We’ll be back with sharper takes, new data points, and more stories and analogies to make sense of where this is all going.

Signing off,

Suarabh Deshpande

Disclaimer: DCo and/or its team members may have exposure to assets discussed in the article. No part of the article is either financial or legal advice.