On Staking

Too much at stake.

This issue was made possible with copious amounts of coffee sponsored by Builda

Want to stay on top of cool projects emerging in crypto without spending all your time glued to Twitter? Wish to use the newest crypto primitives without connecting your wallets to potential rug-pulls? Builda has just the solution for you.

They are building a discovery engine for the discovery of crypto ventures. Rumours have it that protocol grant approval teams dig through their listings to find the hottest new projects to onboard. Take a look at their directory here to understand why.

E-mail sid@decentralised.co if you’d like to sponsor future issues.

Hello!

Humanity has struggled with the concept of ‘truth’ for a very long time. We have bucketed it into different types to help our minds come to peace—absolute, objective, personal. The list goes on and on. The truth can come in multiple shapes if you want it to. In the financial world, the order of transactions determines the ultimate truth, and blockchains facilitate the establishment of these truths.

Satoshi’s genius was in figuring out a way for computers distributed across geographies to arrive at the same order of transactions independently. The ‘independently’ bit is important, as relying on other nodes would mean that the system is trust-based and no different than what already happens in traditional finance. Using blocks as building blocks allows nodes to arrive at the ‘correct’ order. At their core, blockchain networks usually differentiate based on who gets to propose a new block.

The Basics

With Bitcoin, the proof of the amount of work done allows one to propose a new block—hence the term proof of work (PoW). Ensuring the block proposer has done sufficient work shows they have expended resources, such as electricity or mining equipment. It makes spamming the network a loss-making endeavour.

Multiple block producers (miners in this case) compete to produce a block, but only one is accepted. Which means work done by others is wasted. It is difficult to change Bitcoin’s consensus model today, given its age and the incentives of the participants on the network. But newer networks could take an alternative approach.

Proof-of-stake (PoS) systems avoid the race between block producers by electing the block producer. These networks do not require miners to compete with mining power acquired through setting up sophisticated machines and burning electricity. Instead, block producers are selected based on how many of the network’s native tokens a participant stakes.

The earliest version of staking was like fixed deposits. Tokens were locked for a specific duration. The lock duration could be as low as a week. Banks usually provide a higher rate of return on fixed deposits than regular savings accounts to incentivise individuals to lock up their capital for longer periods. While banks use the money in commercial endeavours, like loans, staked assets produce (and vote on) new blocks and secure old ones.

The higher the number of tokens staked, the more difficult it becomes to change the blockchain’s consensus mechanisms because stakers with tokens are incentivised to keep things as they are. In most staking networks, participants securing the network are given a small number of tokens for doing so. This measure becomes the baseline of the yield they receive. Consider watching this video for a more detailed breakdown of how these consensus models differ.

The Opportunity

A whole industry has emerged to assist users with staking with the advent of PoS networks like Solana. The reasoning for this is twofold:

As the table above shows, validators often require sophisticated computers that cost thousands of dollars. Retail users may not have those or want to bother with managing one.

It helps monetise idle crypto assets. Exchanges, like Coinbase and Binance, allow users to stake from their products and capture a small spread between the rewards the network offers and the amount passed on to users staking through the exchange.

One way to measure the market size for staking is by combining the market caps of all PoS-based chains. That figure comes to around $318 billion. Of which 72% is Ethereum. The “staking ratio” mentioned below measures what percentage of the network’s native token has gone into staking.

ETH has the second-lowest staking ratio across networks. But in terms of dollar value, it is an absolute behemoth.

The reason ETH attracts so much in staking is that the yield offered by the network is more sustainable. Why do I say that? Of all the PoS networks, Ethereum is the only one offsetting the daily emissions by burning some of the fees. Fees burnt on ETH is proportional to the network’s usage.

As long as people use the network, any amount offered as staking rewards would be balanced out by tokens burnt as a part of its fee model. This is why the yield generated by the Ethereum validators is more sustainable than the other PoS networks. Let me explain that with numbers.

According to data from Ultrasound.money, ETH will see some 775,000 ETH issued this year for stakers. At the same time, it would burn some 791,000 ETH in terms of transaction fees. It means the supply of ETH is shrinking (by some 16,000 ETH) instead of expanding even after staking rewards are given out.

Think of Ethereum burns in the context of buybacks. When founders (of listed companies) sell stocks, it spooks investors. But when companies consistently repurchase their stock from the open market, it is usually considered a healthy sign. Stock goes up, and everybody’s left a little happier. Typically, in a low-interest-rate environment, cash-rich companies bullish on their prospects opt to buy back their stock instead of using it to purchase other instruments, like treasuries.

Ethereum, with its burn does something similar to buying back stock. It takes ETH off the market. And the more people use it; the more ETH is taken off the market. Ethereum has ‘repurchased’ over $10 billion worth of ETH since EIP 1559 went live around two years ago. However, there is a difference between a stock buyback and a PoS network burning tokens as a part of its fee model: Listed firms do not issue new stocks quarterly.

The assumption is that buybacks get stocks out of the market. In the case of ETH, new issuance (as staking rewards) balances out the tokens that have been burned (as fees). This balance between issuance and burn may be why ETH did not immediately rally after the merge earlier this year.

We did back-of-the-envelope math to see how this compares to other networks. In the chart below, staking market cap refers to the value of assets that have gone into staking on the network. The difference between issuance and burn (through fees) gives the net issuance figure. ETH is the only network we could verify to have a slightly negative rate over a year. It explains why there are so many startups building around it as you will soon see.

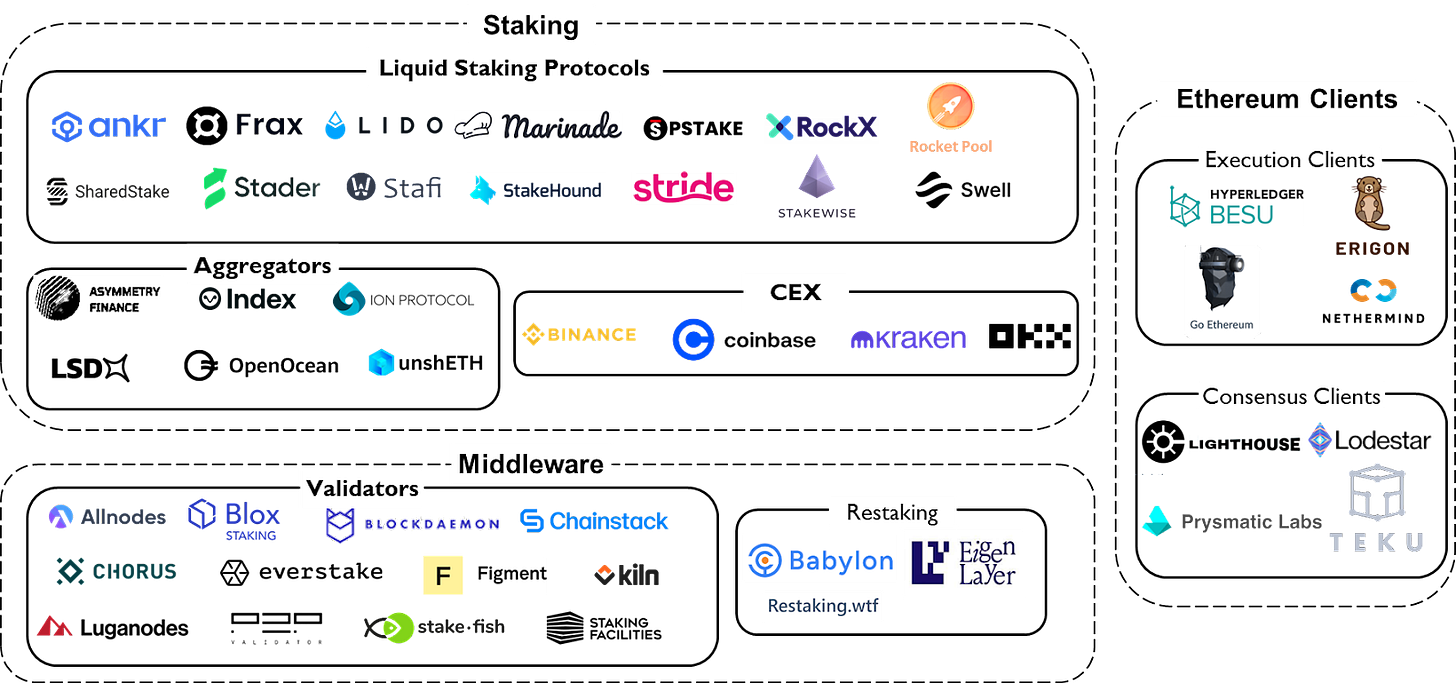

The Landscape

For all the healthy economics around ETH staking, it has a few fundamental issues that make it prohibitive for retail users. For starters, you need 32 ETH to run a validator. At current prices, that comes to around $60k, equivalent to the cost of an MSc in Finance at the London School of Economics. Or what it would cost you to purchase a Bored Ape NFT. It depends on what you are shooting for in life.

That is a hefty price to pay if you want to be staking. The other challenge was that until recently, staking on ETH was a one-way street. The date you could withdraw after committing to be a validator was unknown. This meant you'd be out of luck if you needed access to your ETH for an emergency.

The following chart from Glassnode shows how a new ETH is being staked at a higher pace post-Shanghai upgrade.

Liquid staking derivatives (LSDs) soon emerged to solve these issues. Firstly, it allowed retail participants to stake without losing access to their staked assets. Users could withdraw their yield whenever they wished. Secondly, people with much lower quantities of ETH could participate in staking. But how does this even work? The model depends on:

Giving stakers a receipt-like token that confirms that they have staked ETH in the deposit contract.

Creating pools of ETH and depositing in batches of 32 ETH so that investors could stake in lower denominations of ETH.

Think of the time you pooled money in university for a road trip. LSDs do that for crypto-folks that want to stake. There are three emergent models we have seen in the market with LSDs.

With the rebase model, users get the same number of tokens as the ETH they lock up with the protocol. For example, if you lock up two ETH with Lido, you’ll get two stETH. As you earn rewards from staking, the quantity of stETH will increase daily. Although this model is simple, the changing amount poses challenges for composability across DeFi protocols. Every time you earn new tokens can be a taxable event, depending on your jurisdiction.

In the case of reward-bearing tokens like cbETH (issued by Coinbase) and rETH (issued by Rocket Pool), the token’s value is adjusted instead of the quantity.

Frax employs a two-token model where the ETH and accrued rewards are split. They are called frxETH and sfrxETH, where frxETH maintains a 1:1 peg with ETH, and sfrxETH is a vault designed to accrue the staking yield to Frax ETH validators. The exchange rate of frxETH to sfrxETH increases over time as more rewards are added to the vault. It is similar to Compound’s c-tokens that continuously accrue interest rewards.

Naturally, liquid staking service providers do not offer this alternative to retail users out of the goodness of their hearts. There are profit motives involved. LSD ventures charge a flat fee off the yield a network provides. So if ETH offers a 5% staking yield for the year, Lido would make 50 basis points from a staker .

By this math, Lido makes nearly $1 million in fees daily for its stakers. Some 10% of that is split between node operators and the DAO. It barely has competition from its tokenised peers. Although we couldn’t get data for other major staking derivatives, such as Rocket Pool or Coinbase ETH, we can roughly estimate their generated fees.

For example, Coinbase stakes 2.3 million ETH and charges a 25% fee for staking rewards. Given staking rewards at 4.3% and ETH at $1,800, Coinbase’s revenue is around $45 million for ETH alone. Data from SEC disclosures reveal Coinbase made close to $70 million per quarter from staking across all the assets they support.

Lido has a liquid token with some interesting numbers. Its treasury is one of the few that has accrued substantial value from operating revenue over the past year. As I write this, some $279 million in capital has gone to Lido’s DAO treasury. The last 30 days alone have generated $5.4 million in revenue for the protocol, compared to Aave’s $1.7 million and Compound’s $400k. Stacking up other liquid staking derivatives projects’ fees alongside Lido’s would show you its dominance in the LSD market.

New entrants may eat into Lido’s margins as the staking market evolves, and stakers could move elsewhere in search of lower fees. But for now, here’s what I know—Lido is one of the few crypto projects that make money from idle assets at scale. Some $15 billion in staked ETH resides on Lido. As long as the yield is generated on ETH and capital does not fly out of it, the LSD venture will be in good shape.

Moreover, unlike Uniswap or Aave, Lido is not affected much by market volatility. Lido capitalises on people’s laziness. There’s something beautiful about that.

Note: A more detailed breakdown of Lido’s model can be read from Arthur0x’s thesis here.

The Risk-Free Rate

The risk-free rate is the interest rate on an investment that does not have the risk of default. That is why it is called “risk” free. Typically, government bonds by financially and politically stable governments are considered risk-free. Wait, why are we even talking about the risk-free rate?

In the world of investments, a good or bad investment is judged based on the cost of capital. The fundamental question every investor asks before investing is whether or not the expected return on the investment is greater than the cost of capital.

If yes, then it is investible; otherwise, it isn’t. The cost of capital is the cost of equity and debt.

The cost of debt is pretty straightforward. It is the interest rate you are paying. The cost of equity depends on three factors: the risk-free rate, how risky the investment is compared to the risk-free asset, and the premium for the risk.

Without an established risk-free rate, it is hard to arrive at the cost of capital to judge the basis for any investment.

Take the London Interbank offered rate (LIBOR), for example. It is a benchmark for setting interest rates for everything from floating-rate bonds to pricing derivatives contracts. The rate Ethereum’s validators get is perhaps the closest standard based on which other interest rates in DeFi should be determined.

Current interest calculations in DeFi are broken. For example, the earned annual percentage rate (APR) for lending ETH on Compound is ~2%, whereas the validator yield per the Ethereum foundation is 4.3%. In an ideal world, the rate at which ETH is lent should be slightly higher than the validator yield because:

An application has more risks than the protocol itself. Smart contract risks are mispriced in lending markets.

An investor has little incentive to lend out on smart contracts if liquid staking alternatives offer both liquidity and competitive yield rates, which is the case today.

As mentioned earlier, Ethereum has one of the lowest staking rates. When withdrawals are enabled, the amount of assets going into staking marches upward. The yield per validator will drop as it grows because more assets will soon be chasing limited yield. Issuance of ETH does not increase in proportion to the amount of tokens staked.

Profit motives drive everything around us. If validators notice an opportunity cost, they would take their staked assets elsewhere. For instance, if the interest rate on ETH for lending or offering it as liquidity on Uniswap is significantly higher than the validator yield, they have no incentive to run validator nodes. In such a scenario, identifying alternative sources of yield for validators becomes critical for maintaining Ethereum’s security.

Restaking is emerging as an alternative avenue for validators to increase the yield they can receive.

EigenLayer is one of the leading middlewares enabling restaking. Let’s unpack this. When you use chains, like Bitcoin or Ethereum, you pay a fee for the blockspace, so your transaction can forever be housed in a block. This fee, can vary between networks. Consider a transaction on Bitcoin, Ethereum, Solana and Polygon to observe how much the costs differ.

Why is that? EigenLayer’s whitepaper explains it elegantly – blockspace is a product of decentralised trust enabled by a network of nodes or validators that rests below it. Users and dApps are all consumers of this decentralised trust. The greater the value of this decentralised trust, the higher the price of the blockspace.

Restaking primitive allows us to go deep into the decentralisation stack and create a market for decentralised trust. EigenLayer allows Ethereum validators to rehypothecate their trust and allows new chains to benefit from the same trust.

Think of it like this. We all know the SWIFT network, used for bank wires, is (presumed to be) secure. What if it could be used to drop text messages to your friends living half way across the world? That is what restaking essentially allows for emergent applications.

It takes the security of one network and allows it to be used for other applications such as roll-ups, bridges or oracles. (No, we do not suggest you attempt texting friends using SWIFT)

The Big Question

All of this sounds well and good, but you may be wondering who uses all these things. We could break it down on the basis of supply and demand. On the supply side, you have three sources.

Native ETH stakers (who stake their ETH on their own),

LST restakers (who stake their LSTs, such as stETH or cbETH), and

ETH LPs (who stake LP tokens that include ETH as one of the assets) who are also given the option to validate other chains

On the demand side, you usually have emerging applications or new chains looking to bootstrap security. Remember the bit where I mentioned SWIFT? Instead of texting, you may want to build an oracle network that parses on-chain data and passes it on to DeFi applications. Or you could be building a bridge between multiple networks.

When Ethereum and a few other layer-ones were developing a few years ago, we were unsure whether there would be one chain to rule them all. In 2023, we have seen several layer-ones operating simultaneously. And the idea of application-specific chains seems highly probable.

But the question is: Should all these upcoming chains build their security from scratch?

We don’t want to jump to a conclusion and say no. Let’s look at what happened with web2 to form an opinion. In the early days of the internet, like with Web3 ventures today, founders had to hack together solutions for payments, identity verification and shipments. Stripe, Twilio, Jumio and the like emerged years later to solve these challenges. Part of the reason why eBay acquired Paypal in the early 2000s was to solve their payment challenges.

Do you see a pattern? Applications on the internet scaled when they outsourced things that were not core to their competencies.

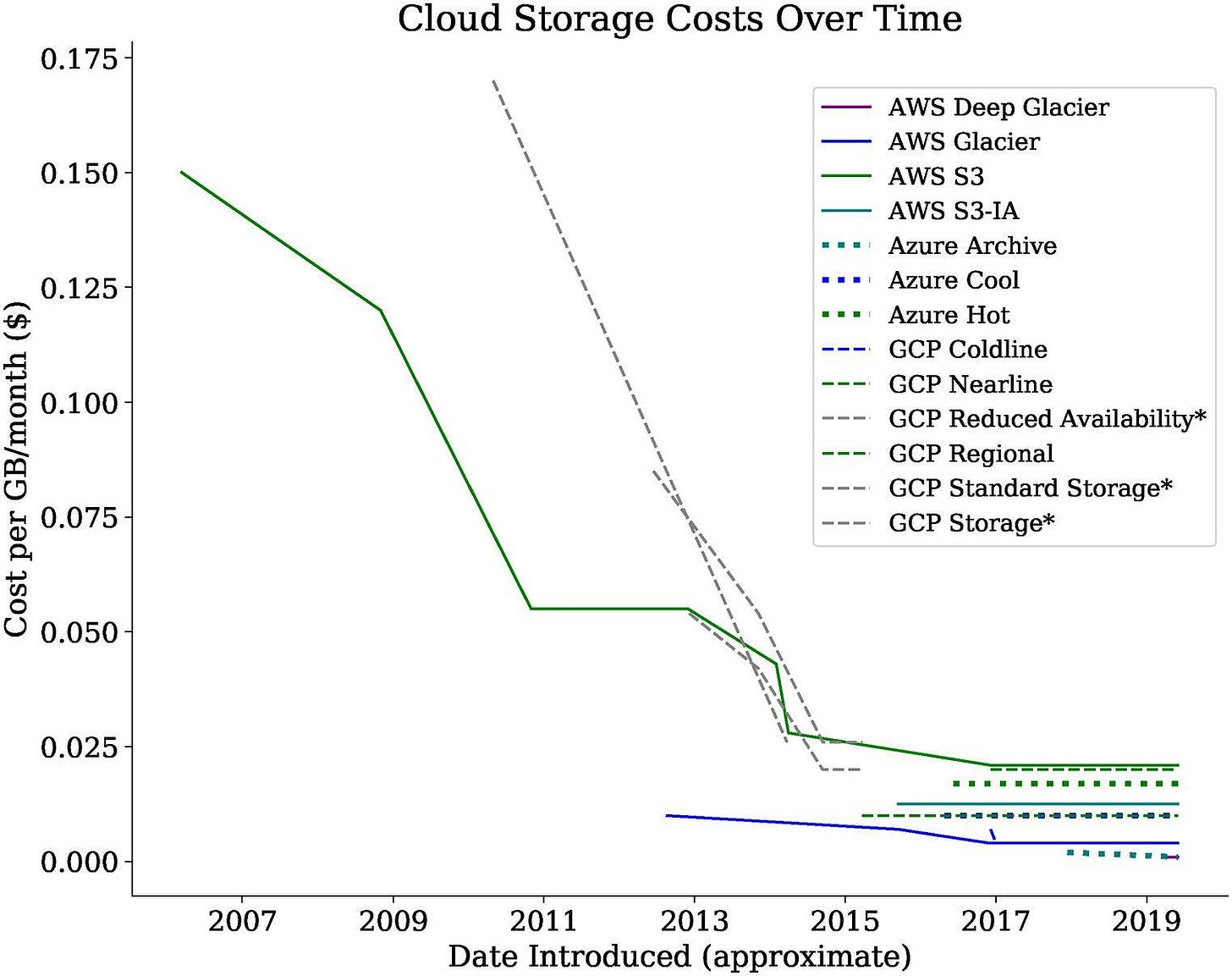

By 2006, AWS made it possible to reduce the cost of hardware by a large margin. A prominent paper from HBR published in 2018 claimed that AWS changed the landscape of venture capital as we know it due to its impact on the cost of experimentation. All of a sudden, you could offer endless streaming (Netflix), storage (Dropbox) or stalking (Facebook) without worrying about purchasing the servers yourself.

Restaking does to blockchain networks what AWS did for servers. You outsource one of the costliest aspects of securing a network. The resources saved by doing so could be better allocated to focusing on the application you are trying to build.

Let’s get back to the earlier question. Should every chain set up its own security? The answer is no. Because not every chain is attempting to be a global settlement network like Ethereum, Bitcoin or SWIFT. There is no absolute security in public blockchains. Blocks are probabilistic (rollbacks up to one or two blocks aren’t unheard of), and security is a spectrum. When you are focused on building an application, obsessing about users is what you should probably do.

Getting your security to a point where you can compete with chains with massive network effects is slow and painful. And if you are an application-specific chain, your users don’t care about security as long as it is sufficient for the application you provide.

The staking landscape is ever-evolving. If institutional interest in digital assets surges due to an ETF approval, it would be one of the few sectors that grow exponentially. There will be opportunities in building businesses that make it easier for traditional clients to hold, stake and lever up on assets that can be staked. We are watching the space closely to understand and collaborate with founders building in the space.

Drop in your decks here if you are one of them.

Signing out,

Saurabh

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

Telegram, Pitch Decks & Referrals.

Join in with over 5000 researchers, investors, founders & overall great human beings. We don’t exactly talk much, but it would help you stay close to what we are focusing on & connect with others building cool things.

Fill out the form below if you are a founder building cool things and in the process of raising money or looking for feedback on what you are pursuing. We like the builders.

Enjoyed reading this? Consider sharing with a friend for access to the paid versions of our newsletter.

great article.