On Belonging

Swifties, city-states and technological standards.

Hey there,

Some notes before we begin.

This post was initially sent to our paid mailing list. I wanted to open up access for the entire community after a few weeks given the relevance of the topic. A handful of users that are both on the free and paid mailing list may receive two e-mails.

We are rolling out beta access to 0xppl to our readers. Think of what would happen if your favourite on-chain explorer blended immaculately with your social graphs from Twitter. That’s 0xppl in a nutshell for you. It allows you to follow investors, traders and your friends to see what they have been up to on-chain.

We might be writing at length about them in the near future, but for today, if you’d like access the app - get your early access code here. They have a waitlist of ~18k users, but our readers will have immediate access.I end the piece with a request for data. I am looking for numbers on retention figures for prominent dApps and networks. If you are a data-scientist or a platform with similar figures, please reach out. I am looking to quantify belonging.

In today’s issue, I explore the concept of belonging. I argue that products, nation-states and artists that inculcate a sense of belonging command a premium over their peers. I struggled to quantify this for protocols. So you will see me go back and forth between the examples mentioned.

This is an idea I am still in the process of developing, so feel free to critique or send examples that fit better in an e-mail response!

The markets have been in an interesting state. Solana's Saga phone buyers received Bonk airdrops, effectively making their phone purchase free. The phone has since sold for over $5k on eBay as owners of the device anticipate more airdrops in the coming weeks. We are trending towards a meme-driven market as the holidays arrive. Alongside volatility and giggles, meme assets bring one more thing with them – a sense of belonging to a larger community.

Protocols have a variation of this. Those with laser eyes on Bitcoin or individuals who willfully ignore how Solana compares (in some aspects) against roll-ups have a particular loyalty to the protocols. They rally around these assets' technical advantages or economic policies as a sense of belonging emanates from their ownership of the underlying asset.

I have been wondering why this happens. Bitcoin maximalists missed out on what Ethereum offers. Now that Solana’s ecosystem is getting interesting, we see Ethereum adopters bashing Solana frequently.

In some sense, the discourse reminded me of the image below.

Investors tend to be loyal to an asset if it has made them rich quickly, even if it is an unrealised gain. This attitude often translates to cult-like behaviour in financial markets where a community coordinates (asynchronously) to move prices. The most prominent example is that of GameStop's last year. Instead of being another trade, the rallying cry behind it was to take down the evil hedge funds that dominated Wall Street at the time – or so the narrative went.

Sidenote: I don't mean to imply that meme assets create the strongest sense of belonging. Given the highly volatile nature of these assets, holders have shared experiences, which tend to make them behave like a herd with a shared mind.

Developers who build through a bear market often have the strongest sense of belonging to ecosystems. The tribalism we see around EVMs and SVMs or design choices made around staking products usually stem from engineers collaborating and building together. With users, this translates differently. You can track them on-chain by noticing how capital flows through DeFi products or the number of active addresses in emerging L2s.

The chart below shows how users flow between prominent L2s as their tokens come closer to launch. It is almost as if users migrate from one L2 to the other to pursue economic opportunities, much like how we see migration between cities.

In other words, protocols, cities and virtual worlds are similar because they derive value from creating a sense of belonging among their users. We create an artificial sense of belonging through creating repeat users. Home pages like AOL or Yahoo competed to provide as much information as possible when the web took off. You could see data on the weather, traffic and pop-culture gossip. They were competing with what was being offered in newspapers at the time.

Sidenote: Notice how they were called “home”-pages. That’s one way to make a product seem more personal. Compare that to the experience you have on opening up Metamask.

As social networks took off, our desire to know what our friends were up to initially powered repeat usage. Social networks eventually figured creators (or influencers?) have far more interesting lives than our friends. You want to see your friend's breakfast only so often. The influencer who concocts made-up scenarios to keep you hooked is likely more skilled (and rewarded by the algorithms) at retaining you on the platform. There is a reason for this. The internet taps into niches at scale.

If I had wanted to talk about Web3 in the suburbs of Bengaluru a few years back, my audience would have been 100 people at best. I know because I’ve tried it. On Substack, with the internet, it scales to tens of thousands.

Derek Thompson best captured this idea in one of his podcast episodes.

The excerpt below summarises it pretty well.

If you go to Tokyo, you'll see there are all sorts of really, really strange shops. There'll be a shop that's only 1970's vinyl and like, 1980's whisky or something. And that doesn't make any sense if it's a shop in a Des Moines suburb, right? In a Des Moines suburb, to exist, you have to be Subway. You have to hit the mass-market immediately.

But in Tokyo, where there's 30-40 million people within a train ride of a city, then your market is 40 million. And within that 40 million, sure, there's a couple thousand people who love 1970's music and 1980's whisky.

The Internet is Tokyo.

Social networks help surface content that taps into niches, assisting users to feel like they belong to the network. A large part of retention on social media apps like Instagram or Twitter is powered by the fact that traditional media cannot compete with the breadth of content formats a social network can surface in micro-niches.

We keep revisiting our preferred social networks due to their ability to surface content relevant to the niches we find most relevant to us. They develop a sense of belonging for users through gathering members of similar tastes. An outcast in the meatspace could feel well at home as communities gather around niche topics on platforms like Reddit or Twitter.

Belonging is what happens when a product (or community) allows us to be our most authentic selves and grow. It is the inevitable feeling a person feels when they are not judged for being themselves. Belonging makes individuals repeat visitors. Be it our favourite cafes, forums, protocols or applications - we return to where we find most comfort without pretence.

Belonging Has Economic Value

Retention is often the after-effect of belonging. If you want users to keep returning, give them a reason to do so. Cities have a variation of this. Hubs like Singapore are tiny city-states that, on their own, have historically had little reason for people to flock towards them, but policy changes attract talent for the long haul. People port over and build there because it is easier to do it there than in the regions they come from.

Policy changes are similar to the incentives we see among protocols. Incentives can drive belongingness as they make aligned users share experiences or similar goals, which could be as mundane as bridging assets to a new protocol or sharing the smart contract address for a new asset. These experiences rally users together.

One product that comes to mind is DRiP. It allows creators to airdrop NFTs at a retail scale (to hundreds of thousands of wallets) at costs that make economic sense. It is partly because Solana has compartmentalised fee markets and compressed NFTs. You cannot do that on Ethereum today. This means a whole group of retail users predominantly oriented towards music and the arts will likely be based on Solana today.

Similarly, Ronin's ecosystem is becoming the new home for gamers. Pixels Online recently became one of the first applications to surpass Axie Infinity's DAUs once they ported over from Polygon to Ronin. It is partly because Ronin had a large, native userbase of gamers seeking novelty. In comparison, the average user is likely not a gamer on a generalised protocol like Polygon. Niche-specific protocols can unlock new levels of growth for applications in specific verticals.

The opposite of this is also true. If you have too many applications with similar offerings, it becomes hard for users to stick to any. It is partly why products like Aevo and dYdX have ported off into their separate ecosystems. It becomes easier to retain and hold on to capital when users have to consider that they need to bridge to a different ecosystem to make a quick trade.

Products that replicate one another in a small market often struggle to create a sense of belonging among users. On the contrary, products that evolve sufficiently to release their chain have the advantage of releasing features much faster as they can tweak the chain to meet niche-specific needs. You can see a variation of this in the arts, too.

I must refer to Taylor Swift to explain why.

Taylor Swift’s era’s tour is expected to generate $5 billion in consumer spending in the United States alone. Her commercial success has been so staggering that Bloomberg declared her a billionaire early this year. It was soon followed by Time Magazine declaring her the Person of the Year. Part of what fuels that growth is the relatability of an artist. Taylor’s work likely speaks to a generation in a way artists of previous era’s don’t relate to a hyper-connected generation that is now becoming old enough to make expensive purchases.

People tend to see versions of themselves in the art they consume and enjoy. So when an artist (or athletic team) they like is criticised, it feels like a personal attack.

One develops a sense of belonging - to one’s creed, religion, nation or sports team, when they tie their identity to it. We see this with technology too. Linux vs Windows. Android vs iOs. Console gaming vs PC. The products we use and the content we consume mould our identity. In return, we develop a sense of loyalty to it.

Web3's original promise was that of user ownership and governance. A user's ability to create, maintain, and scale up open-source products can create a strong sense of ownership. The IKEA effect is a real-world comparison here. The IKEA effect claims people value an object if they make or assemble it themselves. The physical effort of putting together something drives attachment to it.

The software version of this phenomenon likely translates to users feeling a sense of ownership by being early to a product and offering feedback.

The challenge is that most forms of governance in Web3 today require being a power user in some capacity. Aave gave tokens to depositors, but that meant you had to put large troves of capital into their smart contracts. Blur gave tokens to traders, but that implied you had the ETH or NFTs to trade on the platform in the first place.

We have somehow presumed that a user with abundant capital is likely the best option to allocate resources to governing our products. Our default assumption is that users with the most capital should have the most governance rights in Web3 native products. This may be not very correct.

A user with small sums of money may bring non-tangible value to a product by evangalising it or giving feedback. Should such a user not have any say in how a dApp is governed? I’d like to think otherwise.

Profit motives generally drive most power users capable of farming for points (or tokens). Their interests are rarely aligned to cultivate or build value towards a protocol in the long run. In other words, products in Web3 struggle to cultivate a sense of belonging due to the hyper-financial nature of our incentive systems. One way to fix it is to have a community around the product. I have been increasingly observing this with gaming guilds.

When the play-to-earn (P2E) economy took a hit in the post-bubble markets of 2022, many users were left scrambling as their in-game assets dwindled in value – a micro-crisis in its own right. Over the past week, as I have been working on a soon-to-be-published story, I noticed that users gathered together and focused on picking up new skills that could generate income during the bear market.

Community managers were instrumental in helping users find alternative opportunities within crypto. As the sirens of a new bull market begin sounding, those users from the 2021 P2E boom are well positioned to cash in through the assets and skills they have garnered over the years.

Belonging cannot be hard-coded into a product. It is to be nurtured and developed over time. Design choices on social networks or search engines can facilitate it. That is, they can give avenues for people to develop a sense of belonging. The comments section on YouTube or Steam’s game store reviews are “avenues” where people can feel they belong. However, running a search query or buying a game does not develop a sense of belonging for the user.

A different way to think of this is that people have a sense of belonging to their favourite artists or sports teams. But ask anybody if they care about Ticketmaster or similar platforms that allow purchasing event tickets, and you could quickly notice a sense of indifference in them.

In my observation, we tend to develop a sense of belonging when the number of human-to-human interactions scales with shared ideas. Be they protocols, religion or gaming, when people come together to work on a shared goal with aligned incentives, they form a sense of loyalty that is generally hard to replicate.

Communities as Protocols

One way to think of communities is as protocols. When one creates content on the internet, one brings together people from all walks of life. Products like Nansen or Dune are similar in becoming hubs that attract users with shared interests. If these products focused exclusively on brand-to-brand relationships, they would struggle to scale. Instead, they focused on empowering their user base early on.

For instance, if you are an analyst, creating content using Nansen's charts may get you a retweet from their page. That dopamine hit of having a page with over 100k followers distributing your content is a strong hook for analysts to re-use their product whenever they post analyses on the web. When these analysts eventually make purchase decisions at large firms, they would recommend Nansen first due to their loyalty to the brand. (I know because this is what I did in my career)

Similarly, Dune's trending dashboard page is an instance of a product empowering its users. Hildobby - a data analyst at Dragonfly, made his big breakthrough by being discovered on Dune’s trending dashboards. Products can instil a sense of belonging in their users by enabling their growth. The simplest way to do it is through simply surfacing a user’s work and helping with discovery.

As I write this, Hildobby ranks the highest on Dune’s wizard ranking list.

Distributing user content (or enabling discovery) enables products to scale marketing efforts through relatively organic mechanisms. All of this hinges on the underlying product having enough of a use case to attract a critical mass of users. If Nansen's dashboards served no better purpose than Etherscan or Dune had an inferior SQL engine, nobody would bother making content around them.

Enabling collaborations between tribes formed around a central idea helps scale systems beyond what they may be capable of individually. One instance I have seen is Balaji's work around Network states. His central thesis is that nation-states would eventually recognise online communities coordinating (crowdfunds?) capital to acquire territory worldwide. Though it may seem like a far-fetched idea, the central content (the book) has since inspired meetups worldwide, such as this one in Austin, Texas.

A group of people rallying around a central idea is nothing new. Both religion and nation-states evolve and are sustained by individuals aligning themselves with an idea and finding a sense of belonging in them. One way protocols have seen this replicated is by developers flocking around a solution due to its ability to solve a problem personal to them. For instance, DeFi enables the creation of open-access financial products that may be hard to create in a highly restrictive TradFi environment. But that is still oriented towards developers. How do you replicate this among users?

We used to think allocating ownership of crypto products using tokens may generate a sense of ownership among users. But as we have seen, that may not be the case. Users can sell the tokens and move on. An alternative being used in some products is that of points. Points remove the need to handle liquidity, valuations, or community members in trading losses while driving users to a product.

Using points can (theoretically) make users return to a product, post frequently, and use it for a long enough time to develop a sense of belonging. So points should help ..right? Not really.

Points as a Meta

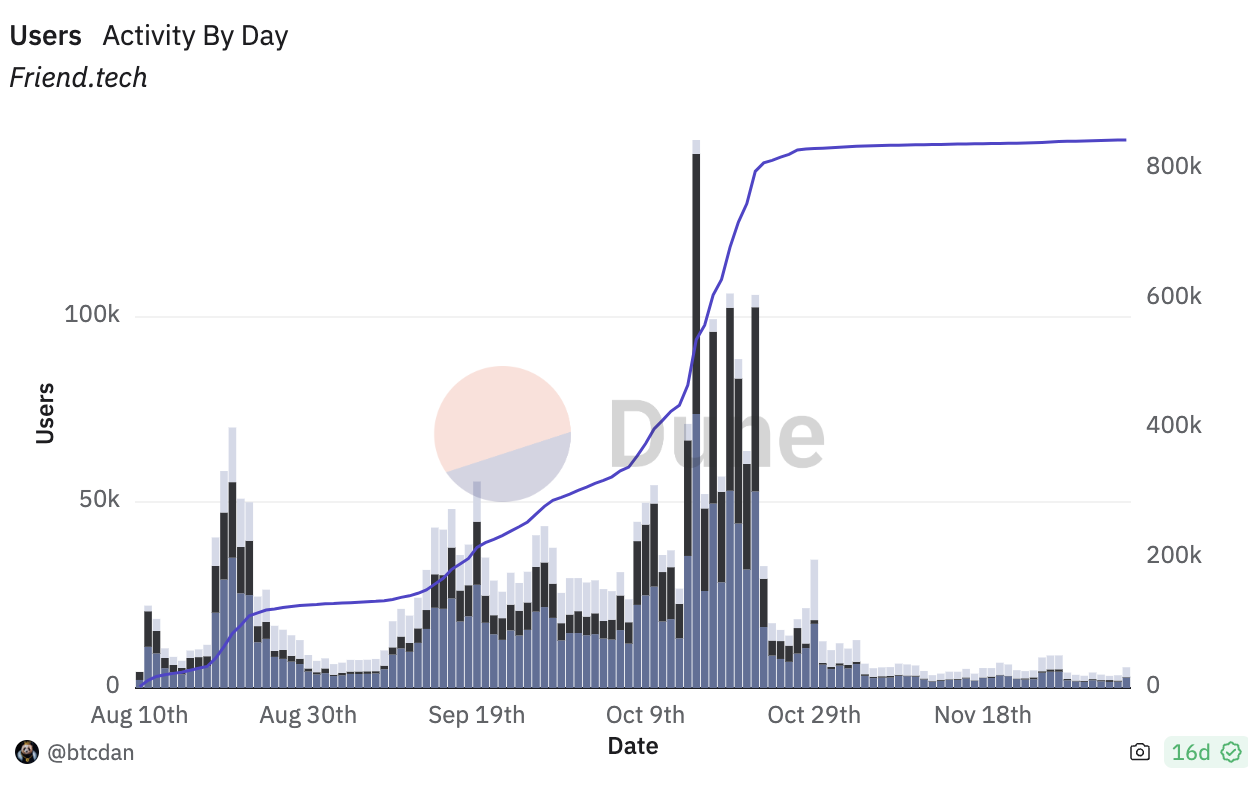

The data below explores how FriendTech’s user base has behaved over the past quarter. They had famously launched a points-based system with plans for a token down the line. It has dwindled from over 100k in October to a little over 2800. Offering points can keep users coming back. But I believe most products have a few weeks before they lose the market’s attention.

If they are unable to develop consumer habits within that period, the product will trend towards becoming a new ghost town. For instance, I signed up on FriendTech, excited about posting on a new platform. However, the lack of new users and a clunky interface kept me from logging back in. This is a trap most web3 social networks will inevitably be walking towards.

Founders may think that issuing points is a new alternative that can fix a lack of traction. It works if you issue a token within a meaningfully short period. Blur had about six months and the boost that came with the NFT ecosystem having a bull market before their token launched. Solana ecosystem's point-based products benefit from the underlying asset (SOL) rallying and users being comfortable taking more risks.

Presuming that issuing tokens independently would attract users is a faulty assumption. Even FriendTech struggles to retain users without a token despite the blessings of folks at Paradigm.

What, then, is the alternative for founders? It reverts to the age-old advice of talking to and learning from your users. Curating community members who rally around what a product does, enabling them to speak to one another even when criticising what you are building, is still vital.

A strong social graph from high-signal individuals endorsing your product can help kick-start a community initially. However, founding teams must still work hard to make communities believe they 'belong' to the product. You cannot write code and hope that people magically care about it. Belonging is a two-way street built through speaking to and empowering users.

Belonging is a strange emotion I likely can't quantify in raw terms. The number of idle BTC wallets that have not moved their assets can serve as a metric. Those users are there for the long haul. But finance aside, our sense of belonging – to a nation-state, a protocol, or family members – has benefits. In the metaverse, this can be seen in terms of how much money users spend on GTA 5. My wardrobe in that game is (arguably) better than the clothes I own in real life.

It makes sense because people have shared memories with their friends. In social networks, it can be seen in how millennials don't give up on Facebook. On protocols, we can see how tribalistic we can be about the networks in which we started our crypto journeys. Bitcoin users stay blind to what Ethereum can do. Ethereum users stay blind to what Solana offers. And Solana users ignore MKBHD’s critique of Saga.

In other words, our sense of belonging can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can make people argue and debate pointlessly. One only needs to look at how conflicts over the ages have emanated from a sense of losing one's religion or land, for example. On the other hand, in a world where products are increasingly digital, and our relationships and social graphs are increasingly virtual, products that inculcate a sense of belonging have an outsized edge over their peers.

Hoping you are spending the holidays where you belong,

Joel John

P.S - The natural extension of this work would be to study how retention metrics on prominent protocols have translated in terms of a valuation premium. But that is a quantitative pursuit for later.

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

- How To Build Product-Community Fly Wheels

- Podcast Episode: Ivangbi from LobsterDAO