Death to Stagnation

A call to action

Before we begin..

Today’s article questions what we are doing with our lives. It also seeks to find answers for it. I map out the sources of revenue and categories in crypto that are rapidly growing. There are mental models that should help a founder within the industry understand where opportunities with little competition exist.

If you read it and enjoy it, please press the heart button at the bottom and spam your chats with the link. The algorithm gods require your precious click sacrifices to show mercy for distribution. Even better if you share it and tag us on social networks. I would love to hear about what you liked, hated, or found amusing in the article. But all that aside..

If you are a founder that is inspired by the writing, please make sure to fill in the form here. We actively advise, invest and help scale early stage ventures. Our research is aimed at guiding founders in their 0 to 1 journey. A conversation could save you a ton of trouble in the coming quarters. And of course, we love to work with founders bringing death to stagnation.

Joel

I’m taking a break from the normal content we post to have a monologue about the state of our industry and what we are doing with our lives. It’s the conversation I’d have with a friend atop a hill over a cup of coffee. But since I can’t host all of you guys together on a hill, we’ll have to make do with cosying up in your inboxes.

This email will probably break in your client, so use this link to read it in a browser. Also, join us on Telegram to chat about what’s written. Let’s go!

Hello!

A few days ago, I noticed an issue with the way we write. Most of the time, our articles cover technical topics for founders and investors. And that is great. We skip the drama, politics, and fraud to be nerds who spend weeks on topics that will be consumed in minutes. But we aren’t in academia. We work in a free market, investing and building alongside founders. So it is important that we stay on top of what is happening around us.

Here’s how I’d sum up the last six months in crypto if I were venting to a therapist:

A 13 year old launched a meme coin and dumped it. Scottie Pippen from Chicago Bulls somehow predicted Bitcoin’s price after a dream involving Satoshi. Speaking of which, Jack Dorsey might be Satoshi. A guy in France made $28 million betting on Trump’s presidency. Which reminds me, Trump launched a meme coin a few days before he took office. Two weeks ago, the president of Argentina tried something similar and wiped out $4 billion in value. His opposition is now trying to get him out of office. People are losing money on Su Zhu’s exchange. And by the way, Hawk Tuah girl launched a token and rugged. Dave Portnoy also launched a token and rugged. CZ spoke about his dog named Broccoli and it looks like that token is not rugged. Yet.

Meme coins now have the power to kick presidents out of office.

Talk about truly large-scale societal impact.

It’s not that good things don’t happen in our industry. In October, the UAE clarified it has no taxes for crypto. In the US, banks can now custody Bitcoins.. Someone made $25k tricking an agent into transferring him money. Oh, and, Marc Andreessen sent $50k to an agent and set the stage for a token that went to a billion. There are talks of the US government developing a strategic crypto reserve. OpenSea might finally issue a token and bail out NFT traders who lost big in 2022. FalconX acquired Arbelos. Coinbase clarified that the SEC has dropped all cases against it. And last week, Bybit survived the largest hack in human history.

Point is, we are a resilient bunch. But most of our collective psyche is wrapped up in all the bad news. The kind that is driven by price with a sprinkle of fraud and TONS of embarrassment. You can’t help but wonder, “Do I really associate myself with these clowns? Am I in a circus? Am I the monkey in this game?” It’s all so tiresome. Especially when you consider that the human brain processes information at ten bytes per second while thinking.

How am I supposed to do my life’s work with a 4k Ultra HD live stream of fraudulent frenzy going on?

If you are not consciously setting boundaries, working in crypto can feel like tossing your brain cells into a vortex of headlines and spinning it at the speed of light until the heat of the sun eviscerates the memories of all that you consider dear and holy. A gradual descent into madness marked by liquidations and the constant stream of never-ending news, that often means nothing. It’s like going in circles around Dante’s Inferno. Skipping from sin to sin.

And this is why we, as a newsletter, tend to be disconnected from the day-to-day drama. But in light of where the market is and what we hear upon speaking to founders, I figured it’s time to do a vibe check on the culture. To address the momentary vibecession we are in, so to speak.

The Age of Memesis

David Perell’s writing on Peter Thiel’s investment philosophy is one of those pieces that defined my career. Mimesis is one of the many things he talks about. Defined by René Gerard, the idea of mimesis rotates around the human tendency to mimic and compete with one another. Think of career choices you may have made at 17. You look at what your brightest peers are doing, or an adult who has the life you want, and you choose their career path. As humans, we are hardwired to mimic and compete with peers because of the high cognitive load involved in forging a new path. We like safety in numbers.

This applies to startups too. Put together enough smart people in a room, and you’ll see them emulate one another and compete with one another. Slap a sense of status on an accelerator or investment fund like Sequoia or Y Combinator, and we’ll likely see groups of smart people wanting to be a part of it. Not merely for the financial resources it unlocks, but also for the status it conveys.

YC understands this and therefore claims to have a lower acceptance rate than Harvard. The status is not what is explicitly sold. But it is definitely implied. And that is why young, driven, ambitious 20-somethings pack their bags and leave for SF to pay exorbitant amounts in rent with the hopes of going further up the status ladder.

When I was 15, I used to wonder why so many Indian VCs simply form their worldview on the basis of what a partner from A16z tweeted on Twitter. It took me a decade of working in venture-land to recognise that they were simply mimicking what ‘big money’ was doing. You don’t need to be original if you can simply copy trade the best. Is that edge? Not really. But it can make money. And this is why you see a slew of ‘me-too’ products in the market. Multiple people mimic and iterate on a concept.

Facebook was not the first social media platform. Instagram was not the first media sharing platform and Spotify was definitely not the first to allow users to stream.

Repetitive iteration helps consumers be better off. At first, the market gets crowded, but over time it decides what gets to survive. So you need multiple founders and multiple VCs chasing the same problem, often with the same solution.

A version of this has played out in liquid markets time and again. George Soros became famous for his trade that broke the Bank of England. Keith Gill—better known as Roaring Kitty—became infamous for sparking the GameStop rally. Both were brilliant at rallying large parts of the market into trades they were already in. Soros convinced traders that shorting the British Pound was a good bet, adding pressure on the Bank of England. GameStop investors squeezed the stock higher until Robinhood stepped in to limit shorting.

What we saw with Roaring Kitty was simply a modern version of Soros’ reflexivity—both were architects of self-reinforcing loops. A big trade attracts attention, people jump in, prices rise, even more people pile on, and suddenly, the asset is at new highs.

Back in Soros’ time, there was no Twitter to endlessly pontificate on the state of the world. In fact, he took a break from markets to study philosophy and write books. But today, you can just publish a meme coin Tier list and rally people into a trade. What Soros called reflexivity is what we now describe as meme coin mania.

People often argue about how financial nihilism is the reason why the average individual invests in meme coins. That somehow, a generation realises that it doesn’t have stable careers, potential partners or a house in the works by the time they are 30 and so they bet big on random tickers from Twitter with hopes of hacking through the very financial system that made them broke (and broke them). But I think that is a rather weak argument.

The real reason is mimesis. Yes, that same thing that dictates what career you choose, which startup YC backs and how Keith Gill made his money, is the reason why you just lost a ton of money on some random ticker named TrumpShibuInuWallDoesnotExistcoin.

Let me explain what happens when the internet breaks down the entry barriers for accessing financial markets and issuing new instruments on the information super highway.

Here’s how it typically plays out. You go through TikTok or Instagram and see a 17-year-old lecture you about the pathways to “wealth” while sharing tickers for the meme coins he traded the day before. The social media marketing manager from work has an NFT that costs a little over $150k on his LinkedIn profile. You see the bills rising and you see an alternative path. A friend shares a ticker in a WhatsApp group. An exchange lists a new shiny coin with a dog that seemingly has a hat on its head. You think this is it. You start with $100, and see it rise to $117. You think what if I had put $1k? Maybe $10k? Before you know it, the credit cards are maxed out and you are “in the trenches”.

Note: To be abundantly clear, Murad’s mention here is out of respect for the outsized influence he has on meme-coin markets. This is not a dig at him. He defines the category today, much like Keith Gill did with meme stocks a while back.

Pump It

In 2009, when Bitcoin came around, it upended how capital formation happens on the web. You could provide “labour” in the form of proof-of-work (the thing that keeps the network secure) and be rewarded with an asset that is Bitcoin. Since the value of the asset rose further in price in the future (due to demand and deflationary pressures), the future value of present labour was higher.

People were incentivised to provide compute to the network and hold on to their Bitcoins. All of this changed when ICOs came around as asset issuance and proof of labour were disconnected. You could mint coins, without labour.

Some $28 billion was raised between March 2017 and 2018. VCs claimed that this is the future of “finance” as it would allow individuals to coordinate capital and resources to bootstrap new networks. It made sense until you realised that too often, the VCs were investing into things at low valuations (say $10 million) and raising for a network at a much higher valuation (say $100 million) in a matter of months.

In conventional VC-land, such madness happened a mere 18 years ago during the dotcom boom. But crypto made it possible again.

Between 2018 and 2023, the market for such token releases matured. We no longer have ICO booms. But we still have a classic game of VCs investing at low valuations to try and list them at high valuations. Talk about an arbitrage.

While there is nothing inherently wrong in investing at a low valuation, there is a lot that is extractive about turning and selling it to retail consumers at a high markup without much progress to show for that spike. Chamath’s SPACs had a similar approach to things during the COVID markets of 2020. On average, the SPACs launched by him are currently down 42%.

Now extrapolate this to everybody getting to be their own Chamath or VC fund at the click of a button. That’s the tooling PumpFun enabled in the last six months. Depending on how you look at it, PumpFun is either the most innovative financial primitive of the last century or the most predatory platform. Reality probably lies somewhere in between. Meme coins are to markets what porn is to media. Much like with porn, it is unlikely that meme assets vanish. So long as greed and human desire to speculate exist, they are here to stay. And a lot of it will fuel meaningfully impactful innovations, much like porn did.

While it is beyond the scope of this newsletter to opine on the morality of it, I’d like to surface two interesting figures.

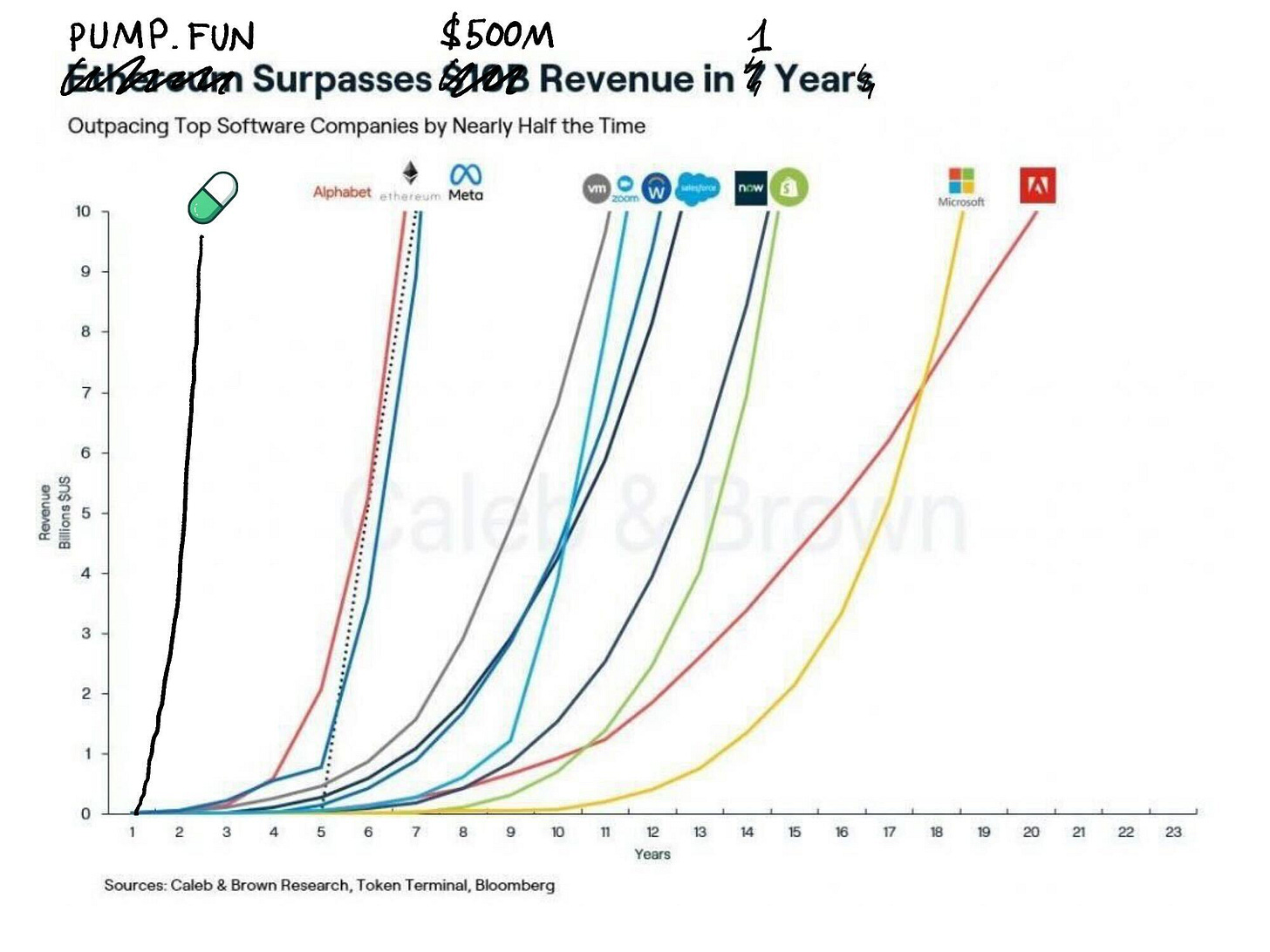

A chart on the cumulative revenue of PumpFun. They made a total of $500 million last year in revenue.

And another one, on the number of new assets issued on Pump over the last few months.

The second chart looks eerily similar to previous cycles of hype. I could overlay it with the number of ICOs launched or NFTs launched and it would look the exact same. There are two parallel realities I am dealing (or coping) with. One is that Pump is probably one of the most profitable startups of all time. The other is that it laid bare the “meta” of how crypto often works. Dave Portnoy intriguingly questioned the basics of what a rug is in one of his tweets.

When we say blockchains enable capital coordination, we do not clarify what the capital is being coordinated for. It could be for cancer research or for mapping out cities. But more often than not, the marginal person on the internet does not care about either. Everybody cares about profits and avoiding losses. We are adults with bills to pay and dreams to chase. So you have a market where everybody is betting on the most speculative investment while both capital and attention decline from things that truly matter. And that my friends, is the state of the market.

The true impact of PumpFun can be explained by the fact that it took crypto from a niche to tooling for the masses. When influencers, presidents and countries launch tokens and see their prices decline rapidly, we are not using crypto for wealth generation the way Bitcoin did back in 2009. We are mostly eviscerating it. But much like the outcomes of what individuals express on the internet cannot be defined by the creators of it, the outcomes of a market cannot be predicted by the tooling that enables it. The people who made TCP/IP, for instance, do not have a say in what I communicate in this newsletter today.

So this mania is the price one pays for releasing the genie out of the bottle.

You cannot have free speech without a willingness to hear a few offensive things. You cannot have tooling for free markets, without the probability that much of it aids greed and speculation. Especially when the consequences of launching an asset that rugs are little to none in an age where the regulator is sleeping at the wheel. Free speech works because there are consequences for saying things you should not be saying. How will a free market work without consequences? This is the great question crypto is trying to seek answers to. But as with most things, markets find their own solutions given enough time.

Meme markets actually rhyme a lot with blogging and personal expression on the web. In the early days, having a blog was a niche activity. You could launch one, but not everybody would read it. I love seeing old WordPress blogs on the internet because it is reminiscent of a time when people wrote to express, not to influence. Up until a few years back, meme assets were the same. Doge is special specifically because the founder did not launch it to make it a “meme”. As the tooling for meme assets evolved, everybody could launch a meme coin. Just like everybody could launch a Facebook page.

In the case of social networks, attention eventually funnelled down to a few creators. In the case of meme assets, capital will eventually concentrate on a few key names. The challenge is that people will lose money while they form maturity.

So where do we go from here? Are we “cooked” as the Zoomers would put it? Is there light at the end of dawn? Do I need to find a different sector to build a career in? WHAT DO WE DO!?

I’d be lying if I didn’t admit I’ve thought of these questions quite a few times in the last two quarters. That is not because I have lost my faith in what crypto can do or become. It is because of how attention has been distributed. And the only solution I find is to have my reality rooted in human interaction instead of what the influencers on Twitter seem to be talking about.

Every time I see my feeds get filled with the latest scam, I have a conversation with one of the founders in our portfolio and have my faith restored. It is, perhaps, the greatest privilege of working on Decentralised.co. We get perspectives from founders that are beyond what the feeds have to offer.

So if I had to zoom out and look at what is exciting, and what would define the next decade, this is how I’d play it. Think of it as a blueprint.

Respect The Pump

You just read me rant about fraud and the lack of essence in crypto for the last ten minutes. If you’re still here, strap in for a dose of optimism and the reasoning behind why all of this matters.

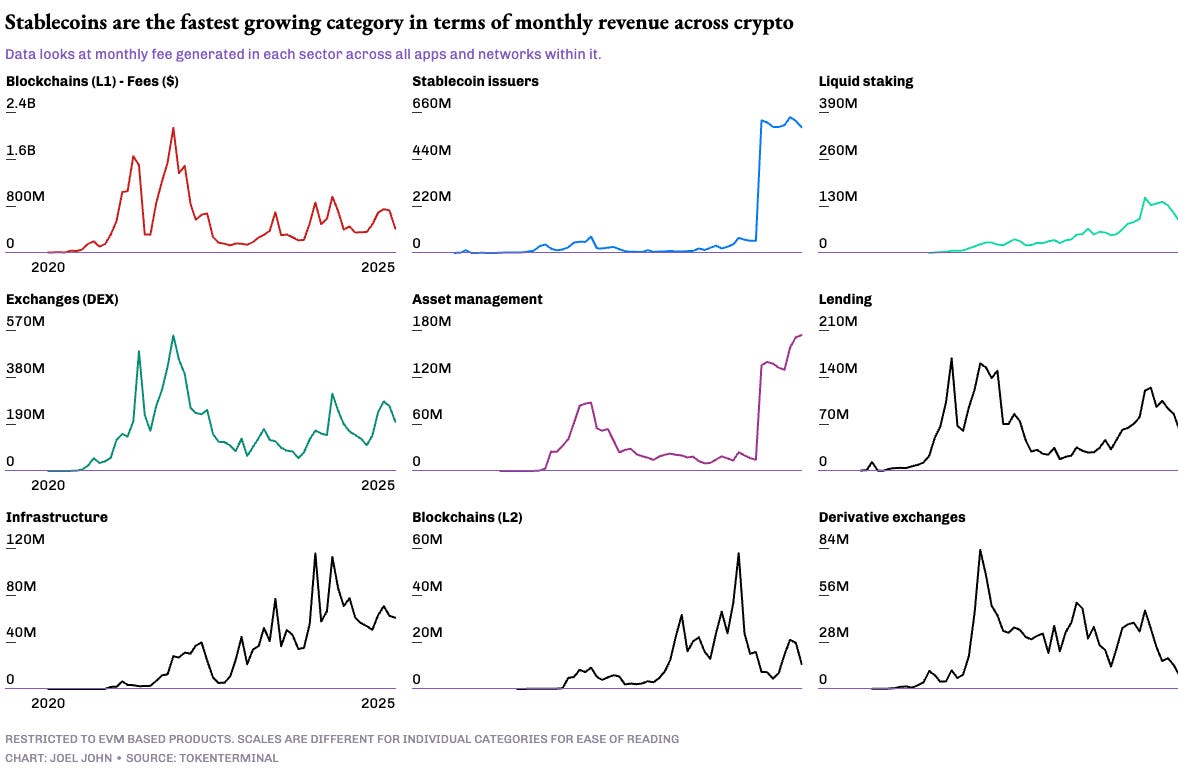

For starters, let's consider the suite of applications that do make capital because directionally it will give us an idea of whether any of this is worth spending time on. TokenTerminal does not track all the applications we would have liked to see. They are slightly EVM-skewed but they do have the best data on price, revenue and earnings. So I started my enquiry by observing what the top ten categories in terms of revenue are doing.

The revenue figures you see below are by month for each year across the decade. It is granular because we want to play the skeptic. And we want to see it grow, because hey, what’s the point in being in a stagnant industry? WE WANT A HOCKEY STICK.

When considering revenue, you see three phases of growth for the industry.

First, is what I would call the dark ages. The era before Ethereum smart contracts became a thing. Up until 2018, blockchain transaction fees were the primary source of economic output in the industry. Surely you could consider miner revenues and associated businesses (like Coindesk) but they are not applicable to the marginal person. Developers are not benefiting from it directly.

Between 2018 and 2022, you see an explosion of applications and use cases. Revenue went beyond transaction fees to the chain itself. You can see the gradual decline of “Blockchain L1” fees making way for things like exchanges and lending. This is what I consider the era of enlightenment for crypto. A magical time when man questioned the limitations of what blockchains could do and went against the dictums of our lord and saviour Satoshi to create alternative business models.

It was during this Age of Enlightenment that we had models like Play-to-Earn (Axie Infinity) and yield farming take off. Surely, some of those chapters ended badly, much like political allegiances in medieval Europe. But it paved the environment for people to question what is possible and sent them down new paths.

Post-2022, we see a new category taking off considerably faster. No brownie points for guessing what I call this. It is the Industrial Era of Crypto. Much like how humanity noticed the ease of using machines to manufacture and transport goods, those working within crypto noticed the possibility of revenue that scales without human intervention.

The alchemy of this age was stablecoins. Everyone wanted yield and the fast movement of money. Fintechs still relied on banks, who in turn relied on governments to dictate how money moves. Stablecoins abstracted the rules that historically existed for fintechs and enabled a new generation of businesses. Tether and Circle have collectively made over $5 billion in a single year.

According to the Economist, stablecoin value transfer hit $2.76 trillion last year, roughly 2/5ths of all value transacted via blockchains. This is up from 1/5th in 2020. The same story suggested that in March of 2024, stablecoin transactions accounted for 4% of GDP in Turkey. This piece is not about stablecoins either, so I will curb my excitement.

Now that we have established the sector makes revenue and that it has reached the scale of a few billion, it is worth exploring how sticky the revenue is. Revenue in crypto can be seasonal but at scale, it can change lives. Think of OpenSea, PumpFun or the P2E craze. Surely, one can argue there was a great “bubble” that ruined lives through NFTs or meme assets.

Questioning whether markets are zero-sum games is beyond the scope of this article (and the levels of existential crises I want to put you through). But one way to think of it is that the revenue during these cycles was so high that it made as much money as most firms do over a lifetime.

One mental model to be used with blockchain native applications is that there will be varying levels of product maturity. And depending on where we are in the cycle, the speculatory premium attached to the product will increase. Consider stablecoins, for instance. It has reached a point where large enterprises can use it for remittance. And that is why we saw a billion-dollar acquisition in that area from Stripe last year.

On-chain analytical tools selling to governments (like Chainalysis) and smart contract audit firms (like Quantstamp) have also reached both maturity and scale of revenue. These are businesses with meaningful cash flow and large enough margins to attract traditional pools of capital.

If you overlay these concerns, you get a matrix. One end of which is centralisation and decentralisation. The other end is seasonality. Extremely seasonal apps like FriendTech may be centralised but struggle to be value-additive to the ecosystem as they rarely pass on value to the marginal user. Uniswap, whilst being mostly decentralised, struggles to give value back to its shareholders. This is why last year they began adding a fee switch to their front end. Cumulatively, it has generated close to $103 million in fees for Uniswap labs since then.

It feels as though the commercial needs of an entity—revenue, margins and control of how the capital is allocated, often struggle with our desire to decentralise and pass on value to users.

A handful of companies have been able to find a middle ground. One that is equal parts innovative, decentralised, passing on value to users and with sufficient scope for growth.

My personal favourite among these is Layer3. If you are hearing of Layer3 for the first time, think of them as an ad network that has aggregated one of the largest user bases in all of crypto. They help new users find crypto-native products on a native basis and reward users with either dollars or crypto for trying them early on. So if you’re a new app or a newsletter like ours, instead of running an ad on Google for untargeted eyeballs, you go to Layer3 to get a curated subset of users that are crypto-native. Unlike Google, Layer3 passes on much of the value generated back to its users as incentives.

In the past, I’ve written about how they aggregate users. On average, they see about ~60k transacting users on the product each day. They have passed back ~$1.4 million to users this last quarter alone. Over the year that number is at $5.8 million.

In the world of ads, that may be nothing. Kanye West spent a bit more on his Super Bowl ad. But the point here is that the $5.8 million is interesting because it is the earliest instance of a product sending value back to its users. It is an open-ad network where the consumer (i.e., early adopter) is compensated in raw dollars through money pipelines that work at a global scale.

Anu from Working Theorys has a beautiful framing for zero-sum vs positive-sum products. She suggests that some products tend to reduce the usage of other products. For instance, you would either use Google Docs or Notion. A firm rarely switches between both due to the lock-ins that come with each product suite. You will need to manually port over the whole team. But some products tend to be positive-sum. That is, you could use Perplexity, Claude and ChatGPT on the same day for different use cases. These products do not eat into the market share of one another until a user’s taste is defined like we saw with Google vs Bing.

Extractive products tend to be zero-sum as they leave the (average) user worse off. Markets are not a zero-sum game if there is an underlying economic case to be made. Someone buying Tesla stocks in 2018 did not need someone else to lose money to make gains when it rallied in the years that followed. You can argue that the stock followed a pattern that was in correlation to the output of Tesla, the firm. But in meme markets, the game feels increasingly negative-sum.

The reason for that is fairly simple. A user needs someone else to put capital into a pool for the asset to price higher. Which in itself is fair game. That is how all capital markets work. But then the user also needs the vibe to stay the same way for prolonged periods. So from the get-go, you expect the mania to stick. Which is still fine because the greater fool theory would dictate people buy the asset. But as numbers go up, people rewire their own “net worth” on the basis of thin liquidity pools. A coin related to Congo, for instance, went to $1 billion in FDV with less than $5 million in its trading pool. People “reprice” their net worth based on this new imaginary capital and when the game inevitably ends, they are usually worse off.

Products like Layer3 are positive-sum in the sense that they do not extract value directly from their user. If you used their tooling and simply hung around long enough, you’d be up thousands of dollars simply by virtue of being an early adopter. As crypto crosses this initial chasm of users, we will increasingly see products optimising to be positive-sum as that is how you build a critical mass of users. The more users Layer3 has, the better possibility its team has to negotiate better deals for users.

Even marketers are better off with positive-sum games because they understand that the user coming from Layer3 is more skilled and experienced because they have used several associated products.

One way to think of crypto’s current revenue state is through the lens of what I consider the marginal adjacent user. In nascent categories, founders are often better off solving for niche problem statements. In the 1970s, Steve Jobs and Wozniak set out to build computers for enthusiasts who were comfortable with the technical aspects of a computer but needed something portable and affordable enough to have at home. Niche, technical, expensive and extremely targeted. Contrast that to what Jobs was doing in the 1990s. He was obsessed with taking the technology to the masses. Less technical, more general purpose, relatively price sensitive and incredibly user friendly.

If you were building in crypto until 2021, it was fine to build for the user that was already active on-chain because your revenue per customer was high enough. In a market where there is curiosity, selling novelty works. But as users lost money and interest in the years that followed, expanding the pie began to matter. Few chains and apps (mostly on Solana) did a good job at it and captured the next wave of users that came onchain. The risk is that these products do the same thing DeFi did in 2019. Marginally faster, cheaper and arguably a better experience, but it does the same thing.

According to Mary Meeker’s last report, there are some ~3 billion people on the internet today. By best estimates, there are between 30 to 60 million monthly transacting users in crypto. That is quite generous in itself. But consider that there are multiple products competing for the same users all the time. In essence, what you have is sectoral cannibalism. A point in time when a market does not grow fast enough to accommodate multiple players within it.

So teams compete either on (i) pricing (ii) incentives or (iii) features to a point where they die due to a lack of margins. A literal race to the bottom.

What is the alternative? It is to build things that can go mainstream because both moats and margins exist there today. The popularity contest we have within crypto for who has the highest TPS or who is more “aligned” works for the feeds but does not pay the bills. Layer3 intrigues me because they are not going after the users that are here and now today. They are expanding the pie. And capturing a share of the value generated.

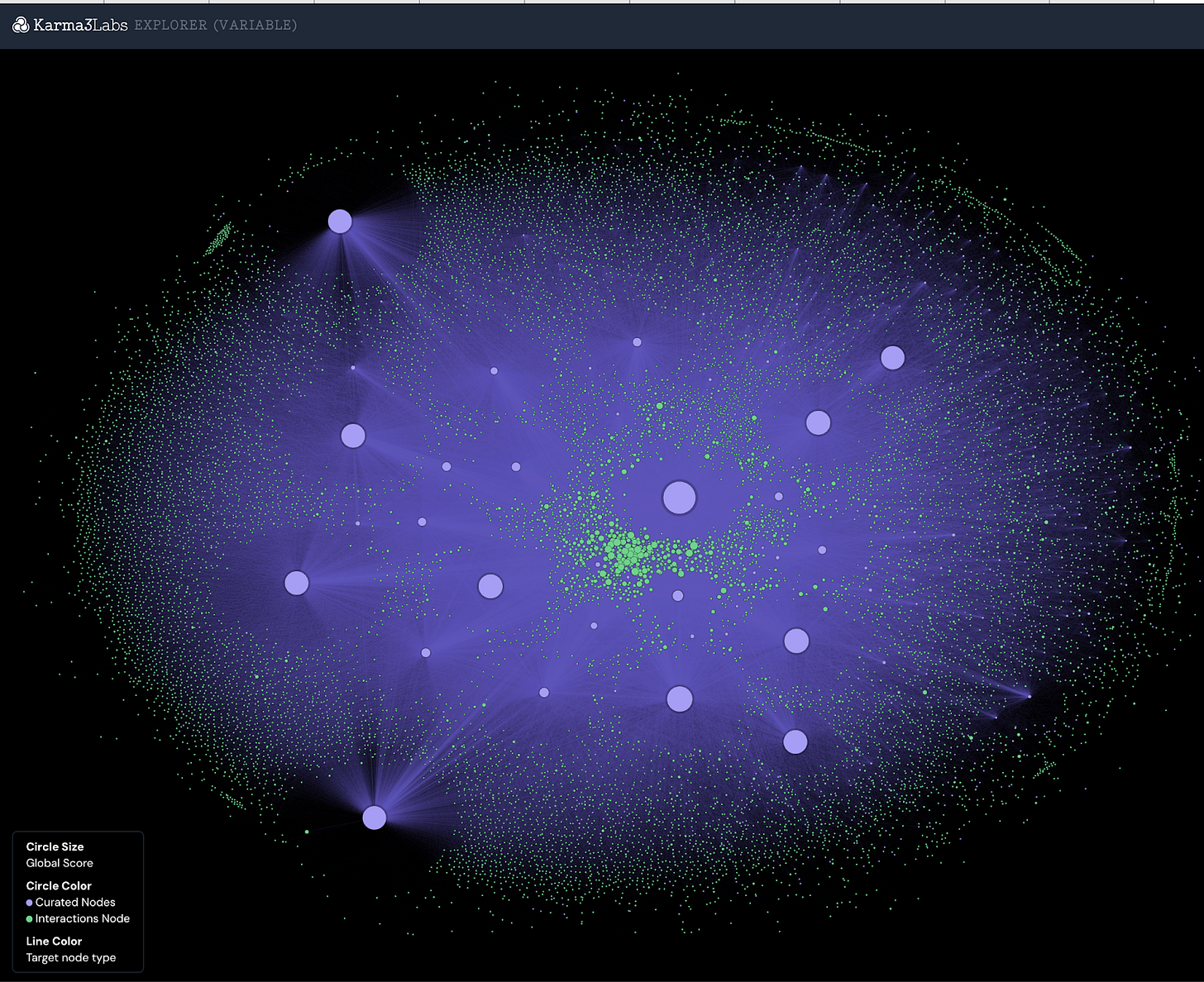

This theme of expanding the pie is not native to Layer3 alone. OpenRank is a product built on top of Farcaster. Since user activities on Farcaster are often relayed on an open network (a blockchain), it is fairly easy to assess which users are value-additive and which communities are organic. OpenRank helps identify the right users to directly incentivise them with tokens, NFTs or early access passes. This means any developer can target any user on the social network.

Layer3 and OpenRank are two separate approaches to advertisements in the age of blockchains. One curates protocols, users and incentives. The other allows the market to identify users on an open network and directly target them. Whilst it remains to be seen how Farcaster evolves and which of these ad models stick, it is safe to suggest that blockchains are making a dent in how value is transferred on the web in the context of content. Surely that market is niche today but they can see exponential growth.

One of the instances where I’ve seen this personally is with stablecoins. In 2019, if you looked at their combined market cap of ~$1 billion, the odds of you thinking these would be worth $204 billion five years out are quite low. And yet, that is where the collective market cap of stablecoins sits today.

The big question, then, is can the market for crypto-adjacent users be just as big? Can they grow to be a few hundred million users in the next five years? And what would it require to build a world like that?

We are getting some early hints of the answer in parts of the industry that interact directly with hardware networks. Frodobots and Proto for instance use points or tokens (like USDC) to incentivise mapping out geo-spatial data. Frodobots ships physical robots to users who are then expected to ride them through the town. The product then uploads the data to create the world's largest urban navigation dataset. Proto similarly incentivises users to use their phones to aid with mapping out dense urban networks. What intrigues me about these models is how data can be captured from third parties trustlessly (using device sensors) whilst incentivising them with global capital networks.

A variation of using the crowd to source data for website monitoring is now happening with UpRock.

Prism, a SaaS platform by UpRock, offers an alternative uptime monitoring system with DePIN precision. Their network, comprising nearly 2.7 million devices worldwide, forms the backbone of UpRock, the core consumer product that powers Prism. When developers need insights, they can tap into UpRock’s userbase—many of whom earn rewards for running its mobile and desktop apps to collect data. Could this work on fiat rails? Definitely.

But try making millions of micro-payments across 190+ countries each day and let me know how that goes. UpRock uses blockchains to accelerate payments and maintain a verifiable, open ledger of past payments. It ties it all together using their core token (UPT). As of writing, the team burns UPT when external revenue comes in through Prism.

This is not to imply that we are in a sea of radical innovation that is soon to make tickers defy gravity like Iron Man. No. We are not there yet. The best place to see this distance between where innovation lies and how tickers perform is probably agentic tokens. Let me begin with a selection of charts.

Now that we’re past the hype cycle, it’s safe to ask ourselves if there is anything of value lurking in this sector.

The most compelling intersection of crypto and AI isn't found in agents themselves but in decentralised training and computation networks—using token incentives to train and serve AI models across a globally distributed network of computers and GPUs.

You can see an early iteration of what this can look like with Pond’s model factory. They are incentivising the creation of a model with machine learning capabilities that can mimic how judges might rank open-source contributions.

So, you can gather data (like UpRrock does) and you can also find people to build models (like Pond does). But where do you run these models in a world where both energy and compute are scarce? Shlok actually explained what that would look like in a previous article, so I’ll share precisely what he shared.

Who are these new AI-native marketplaces? io.net is one of the early leaders in aggregating enterprise-grade GPU supply, with over 300,000 verified GPUs on its network. They claim to offer 90% cost savings over centralised incumbents and have reached daily earnings of over $25,000 ($9m annualised). Similarly, Aethir aggregates over 40,000 GPUs (including 4,000+ H100s) to serve both AI and cloud computing use cases. Earlier, we discussed how Prime Intellect is creating the frameworks for decentralised training at scale. Apart from these efforts, they also provide a GPU marketplace where users can rent H100s on demand. Gensyn is another project betting big on decentralised training with a similar training framework plus a GPU marketplace approach.

In other words, crypto has reached a point where we can source data, models, fine-tune them and gather the physical infrastructure required to run AI models. Meanwhile, the average person in crypto is still sitting around asking "when moon?"—completely unaware they’re sitting on a pile of uranium that could take us much further. Some developers do recognise this. Teams like Gud.Tech and Nomy are working towards making transactional agents that can take user inputs, contextualise information and do transactions.

What does that mean? Chatbots have existed since at least 2015. Being able to get information from a bot is in itself not interesting. What intrigues me about Gud and Nomy is how they abstract the complexity of buying assets across chains. Nomy gives you a simple chat box where you explain “Buy 50 po with my eth on base”, and the agent automatically completes the transaction on its own without requiring the user to sign transactions multiple times. Similarly, Gud is working towards a transactional product where the user can almost always be guaranteed the best price by optimising how they source liquidity. These products are blurring the lines between where we consume information (Twitter, newsletters etc.) and how transactions are done. And all of it builds on AI improvements.

Why am I talking of these two teams in particular? Because they are the essence of everything we discussed so far.

They target crypto-adjacent users instead of competing for the small userbase that’s here and now

They are not zero-sum in that they grow only when their users continue to stick around

They are packaging critical infrastructure (like gasless transactions) into a single product that users can play with

And they are building at the edge of crypto x AI in a way that is relevant to the average person on the internet.

I highlight Gud and Nomy in particular as they are built by teams that have a history of perfecting infrastructure before evolving into the application layer. It makes a simple thing quite apparent. The age of applications is here. If cash flow, revenue, moats and user retention really do matter, then applications will be the ones that carry out that mission. Infrastructure has matured to a point where arguing about TPS makes little sense. Our lack of willingness to let go of those heuristics is just another sign of stagnation.

To evolve, we need to change the conversation. Perhaps, even develop a shared language of optimism.

Cathedrals, not Trenches

In the mid-1940s, as the threat of World War II began diminishing, the world of aviation took on a new challenge— building planes that mimicked a bird. A pigeon, to be exact, according to Where Is My Flying Car (beautiful book, btw). The challenge was to build a plane that could land in a backyard, without long runways. Although the efficiencies of planes have evolved drastically in terms of the number of individuals carried and fuel efficiency, we still do not have flying planes that are retail-owned.

Does that mean aviation failed? Not really. In 1961, John F. Kennedy said;

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

In the decades following this optimism, the investment and energy put into making America a leader during the Cold War set the breeding ground for what we know today as Silicon Valley. It gets even more interesting when you consider that, in 1903, the media openly argued that we would not have flying machines for another million years. A million!? Sounds like they were expecting Evolution to handle it for us. But we didn’t wait.

We made it happen. And by 1969, we were walking on the moon.

But the period between 1903 and 1969 saw multiple failed attempts at flying. Crypto feels a lot like that. We’re too focused on perfecting the engine instead of making it useful for transporting people. JFK’s political will gave aviation new energy and direction—rallying people, resources, and policy toward one mission. And this isn’t a one-time thing. It’s a pattern.

In David Perell’s essay on Peter Thiel, he highlights how medieval Europe came together to build cathedrals at a time of destruction and peril. These buildings were symbols of hope that took centuries to build and just as much in resources. They required coordinating finances, security, talent and labour—far beyond everyday efforts.

The average worker building a cathedral could have only hoped to see its completion in their lifetime. Today, the equivalent would be spending 4–5 years scaling a consumer application while much of the industry is obsessing about technicalities.

What we see with meme coins today is humanity grappling with what can be done with money when assets can be issued and traded as fast as sending a text message. We’ve been here before. In the 1400s, we were coming to terms with what can happen when interest rates apply to capital. In the 1700s, we discovered the power—and chaos—of trading corporate stocks. The South Sea Bubble was so bad that the Bubble Act of 1720 was set up to forbid the creation of joint stock companies without a royal charter.

Bubbles are a feature. Perhaps even a necessity. Economists write them off negatively but they are how capital markets identify and evolve into new structures. Most bubbles start off with a surge of energy, attention and quite possibly an obsession with an emerging sector. This excitement pushes capital into anything investable, driving up prices. I saw this obsession recently with agent-based projects. And if it wasn’t for the combination of financial incentives (token prices) and hype, we would not have nearly as many developers exploring that sector.

We call them a “bubble” because they burst. But price declines are not the only outcome. Bubbles drive radical innovation. Amazon did not become “useless” in 2004. Instead, it laid the foundation for what we know today as AWS, which went to power the modern web. Could an investor in 1998 have known Jeff Bezos would pull that off? Probably not. And that is the second aspect of bubbles. They create enough variations of an experiment to bring out a winner at the end of it.

But how do we do enough experiments to see winners? That’s where we need to focus on building cathedrals instead of just dancing in the trenches. My argument is that meme assets aren’t inherently bad. They’re great testbeds for financial innovation. But they’re not the long-term, revenue-generating, PMF-finding games we should be playing. They are the test tubes. Not the lab. To build our cathedrals, we’ll need a new language.

We are already seeing glimpses of this language with projects like Kaito and Hype. I have bags in neither but what stands out is that they’ve become category leaders in their own way. And the prices of those tokens have found steady ground unlike many other VC-backed marquee projects with nothing to show after 36 months of panel talk. More people will rally around this new language as they realise that crypto’s core meta-game has evolved.

In 2023, when I wrote “Has crypto failed?”, I argued that we will trend towards a market where founders and VCs recognise the need for revenue and PMF. That was my post-FTX PTSD hoping the industry trends to rational actors. In 2025, I am fully cognisant that it will no longer be the case. Hope is not a strategy.

What will happen next is that high-agency individuals will create a parallel game where they build their own cathedrals. Instead of chasing clout on crypto-twitter, they will listen to and build for the marginal person on the internet. And they’ll make their money—not from the blessings of exchanges, but from actual product revenue. The fuel for this will come from the same crisis of faith I had at the beginning of this article.

People will start asking, “Why am I even here?”, and switch the games they play.

This split between revenue-generating tools and those that don’t will be crypto’s great divide. At the end of it, we will no longer be talking about working in crypto, just like nobody says they “work on the internet” or “on mobile apps” anymore. They talk about what the product does. It is a language we should be speaking more often.

When I started working on this piece, I was trying to pinpoint what really irked me. Was it the fraud? The meme assets? Not quite. I think the real pain came from recognising the gap between effort and impact in crypto—especially when compared to AI. Sure, we have stablecoins but we also have all these other innovations that people barely know or talk about. And that felt like stagnation to me.

Stagnation is death in a market that is constantly evolving. If you stagnate, you die. But if you kill stagnation, you survive. And that is the irony behind “death to stagnation”. To protect life, you must be willing to kill what is innate and core to you. That’s the cost of evolution. Of relevance. Crypto is at that crossroads now. It must choose to kill parts of itself so that the bits that can evolve and dominate have a fighting chance at growing beyond infancy.

Admiring cathedrals,

Joel John

This article was hugely inspired by Bubbles and the end of stagnation. If you haven’t read it, I absolutely implore you to read it.

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

- Financialisation of Social Networks

- Ep 27- Infrastructure, Empathy, and Grit

long and insightful, thanks, the telegram link does not work