Cynical Optimism

A framework of thought.

Hello!

I noticed some of our readers have been forwarding our paywalled content to friends and family. I want to clarify that we love people sharing our content and have no issues with readers doing that.

If it helps, here’s a link you can use for the communities and group chats you belong to. Share everything we write. Ideas are fungible and infinite. And screenshots make terrible reading experience. With that out of the way, back to work.

My last few articles have been observing the state of the markets as they are today. I observed how narratives drive themes in crypto and followed up with a breakdown of why volatility is a feature in most products. While these articles look at the behaviour of investors today, I’d like to break down a thesis on what the next few years in crypto will look like.

If you go on your Twitter feed, there is a resounding sense of hopelessness. Multiple market-makers have shut down operations, which means liquidity in DeFi applications is relatively low. The only applications making noise are the ones that enable speculation. And despite a decade-long obsession with decentralisation, our killer apps (stablecoins) are largely centralised businesses built on decentralised infrastructure. They are subject to censorship and far from immutable.

In such environments, cynicism is the intellectually easy route. You can be right 9 out of 10 times by simply shooting down concepts. And much like doughnuts, they are highly rewarding in terms of short-term dopamine. We like being right. The cynicism watches out for us by protecting us from potential fraud in the short term. And earns us clout from colleagues in the long term. Win-win, right? I wish.

The problem is while your odds of being right are 90%, that 10% of the time when you are wrong is usually the land of outlier outcomes. So when you are wrong, you could be passing up a potential opportunity to invest in Google, Uber or, as I’ve learned in my career – Polygon at a $10 million valuation.

I won’t make this a post about why cynicism can be costly. Instead, I want to lay a framework of thinking for the next few years. Technologies evolve when a counterculture is formed. That is, early adopters of technology tend to think applications or protocols built using it should work in a certain way.

Eventually, people closer to markets make tools with trade-offs that look strange to early adopters. The new entrants look like the counterculture. As these new entrants build tools to scale, the technology gets adopted, and the early entrants get left behind.

An emergent counterculture (like NFTs or DeFi) has not displaced early adopters (like the laser-eyed Bitcoin bros) because blockchains enable ownership. The growth of Bored Apes does not diminish Bitcoin’s value for a holder since 2011 who purchased drugs and forgot the existence of his wallet up until a few weeks back. Crypto is unique because it has enriched early adopters, regardless of their ability to contribute.

Much like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates commercialised operating systems by licensing them, we will have a point in time with crypto-native applications when the apps that scale go against the ethos of what the industry has stood for.

Let me explain why.

The Killer Applications Are Here

It has been nearly 15 years since Bitcoin’s whitepaper was released and almost 8 since Ethereum launched. To presume we are in our infancy as an industry is a good excuse to make when we fail. I think the applications of scale and PMF are already here and now. Consumers do not consider them as useful as Instagram or Amazon due to regulations, product positioning and technological limits. Let me explain.

Depending on the statistic you go with, global remittance settlements range between $150 billion to $600 billion on any given day. According to data from Artemis, some $18 trillion have been settled on stablecoins over the past half a decade. The YTD volume for stablecoin settlements is $3 trillion. Surely, the vast majority of it is not retail-focused. If I presume a 1% rate ($30 billion) being retail users and take the high end of remittance volume ($600 billion), stablecoins have covered 5% of the remittance market.

You can scratch all those metrics and argue that they are simply wash-trades between users depositing to exchanges. That could be the case, but consider that the stack enabling large-scale dollar transfers between users exists here and today. USDC on Solana settles almost instantaneously, with transfer costs so low that the developer could pay for all of the user’s transactions on a wallet they develop. For scale, consider that some $400k was spent on gas costs for stablecoin transfers just yesterday.

Why, then, haven’t stablecoins taken off in the retail psyche? A significant reason is the lack of regulated players. Tether has been controversial, and anybody building applications on top of them stands the risks of USDT going to zero. It may seem like a far-fetched hypothesis, but several yield-as-a-service fintech apps had to close shop last year when Luna collapsed. (Yes, I’m comparing apples to oranges here.)

Earlier this year, Circle’s USDC temporarily depegged during the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. While stablecoins are a killer application, no regulatory frameworks exist for trust in these systems. That will soon change with the Monetary Authority of Singapore and the Financial Services Regulatory Authority (Abu Dhabi) issuing frameworks for stablecoins. The emergence of regulatory clarity around stablecoins as an asset will mark an inflexion point where the ‘use’ of stablecoins will be less oriented around trading and more towards retail use cases such as remittance and B2B payments.

A different place where we have already found PMF is with DeFi. The markets quickly discount the segment because we ‘value’ it based on how tokens perform. According to DeFiLLama, some $40 billion is spread across DeFi native products in TVL today. If it were a bank, it’d rank somewhere around #40 in the US based on deposits.

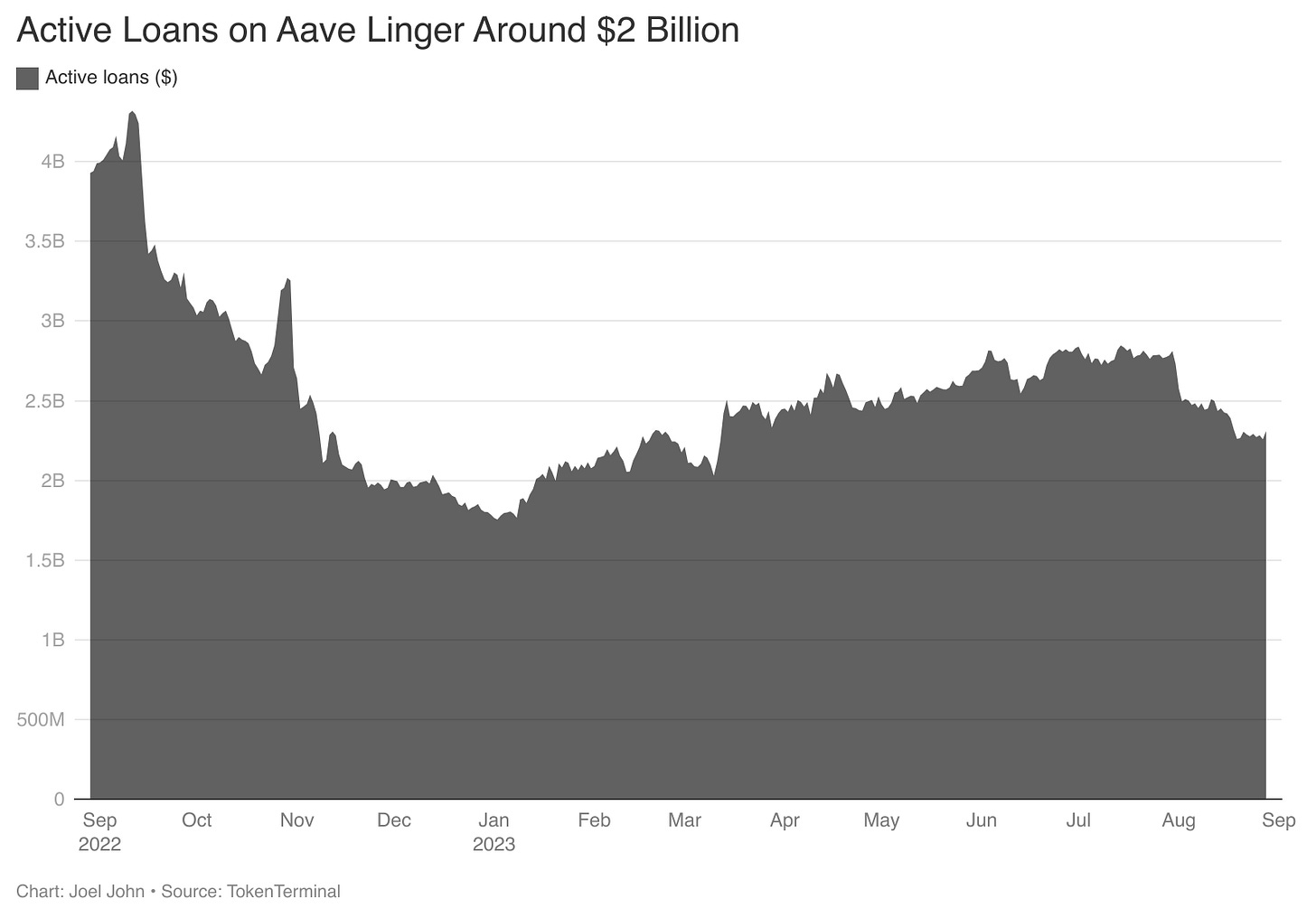

Aave has over $2 billion in outstanding loans, while Uniswap processes trades from a million users monthly. The last seven days alone saw over $3.8 million go back to liquidity providers on the product. Are these systems perfect? Far from it. However, they offer a permissionless, censorship resistant, user-owned alternative to the traditional banking world.

NFTs have a similar growth arc over the past few years. Many of us tend to see the ecosystem’s growth (or collapse) by measuring the price of NFTs or the frequency with which they change hands. But at a fundamental level, they are tools that verify if the intellectual property being purchased by a person truly belongs to the seller.

It is the equivalent of verifying whether a Gucci or Louis Vuitton bag is an original. Over the past few years, NFTs have done these ‘verifications’ over 277 million times. Some $43 billion in value has exchanged hands on Ethereum alone in NFT volume. Nobody ever spends time verifying whether an NFT is fake or real. Smart contracts do that job.

Stablecoins, NFTs and DeFi are similar in collapsing the marginal cost of verifying economic activity. I’d written more extensively about this in our piece on aggregation theory. But the broader points to be observed are as follows:

Blockchain’s core value proposition in the past five years was as a payment enabler. When I send someone $100, the person’s balance increases and my balance decreases. Blockchains enforce this in an exponentially more transparent mechanism than banking ledgers.

Regulatory choke points meant that historically, the use cases had to be restricted to speculation. But we have improved exponentially within the scope of payments in the past few years.

As the regulatory landscape evolves, more retail-oriented applications will launch with an obsession for scale. They will make security trade-offs that look strange to early adopters.

The big mistake most investors would make in the next few years is thinking the current speculatory landscape in crypto is what the technology could eventually enable. The risk we all face is misjudging the timelines with which these changes could occur.

I have an emergent thesis about what could flip the switch. The answer requires us to look at things beyond the blockchains we obsess so much about.

Needs Produce Scale

We struggle to find a ‘killer use case’ for crypto because we see it as a singular infrastructure that functions independently in a world separated from external linkages. The internet was similar for the longest time, as people used it only for e-mail and chat, while the core subset of users was academia trying to share research.

Founders like Jeff Bezos, Sergey Brin and Travis Kalanick were building links to the real world. Let me explain through the lens of their products.

Amazon – It built catalogues of offline products and made them available online.

Google – While Google initially indexed the online world, much of the ‘value’ they built was in enabling individuals to find businesses whose presence was offline up until that point.

Uber – It got offline networks of taxi operators to move online.

Airbnb aggregated, indexed and curated information on who is open to sharing their house with you. Real estate (or rooms) is an offline product.

In other words, rewards are earned by blurring the lines between offline and online. Social networks (like Meta) are interesting because they have bridged the offline and online worlds. You can sit glued to your screen all day and have a relative sense of what is happening in the real world.

The question we should be asking is not what can be built on-chain but what elements of technology can blend with blockchains to enable applications that can scale.

Uber is an excellent example of how technologies blend to create magical experiences. In 2009, you could walk up to a person in India and ask if they’d like to call a taxi using an iPhone. The iPhone would have cost you $1,000, the internet to run the app would have cost you another $10 (each day), and the taxi might have never come. Mobile devices were a luxury then. It would appear stupid to use a mobile app when you could just ring up a taxi driver.

In 2021, people in cities rarely hailed a cab directly. Uber has built consumer habits to a point where it is strange not to use the app.

(Sidenote: One of my favourite Uber facts is that they have a real-time bidding system in Lebanon because of the region’s currency fluctuation. It is the only region you can haggle with a driver in the app.)

In 2009, for Uber to work, you needed three separate networks to function:

The GPS, which has been in development since the 1980s

Payment rails, which have been in development since the 1950s

Mobile networks, which have been coming of age since the 1990s

These had to merge into a mobile device that benefited from five decades of Moore’s law. We take these things for granted, but technology evolves only with decades of work blending. The smart entrepreneur can tap into multiple trends blending. (I would give Travis a premium for his ability to navigate taxi unions globally, but that is out of the scope of this article).

Blockchain’s next killer application will not emerge because users want to speculate. It will be embraced out of necessity, just like stablecoins and DeFi were. The internet’s current landscape is evolving, and there are two things the technology does exceptionally well – verifying data and verifying identity.

At its core, a transaction is just two things: the identity of the individuals involved (say Alice and Bob) and the amount transferred between them (say $50). The blockchains we consider with such high regard (be they Bitcoin, Solana or Ethereum), at their core, do the same function. They act as ledgers.

They store data about individuals engaged in a transaction. And we have perfected that process. Tools like Nansen or Arkham are visual layers for identifying the individuals or patterns that emerge from this data. We are doing a long-form piece on identity and data in the coming weeks, so I’ll avoid going into detail on it, but here is why I think the next phase of adoption would blend with emergent technologies like AI.

The web is undergoing a transformative phase. Generative AI will soon create more content than humans can consume. It is within the realm of possibility that we see machine-generated content taking over human content in the next few years. Human moderation can barely keep up with human content to begin with. Meta has tens of thousands of underpaid employees to help moderate content on their platform. What happens when machines create more content than humans can moderate or consume?

The web will slowly become fragmented, and we will need tools to verify the source and accuracy of information. We consume content from social networks that face a trust deficit today. Twitter integrating a ‘community notes’ feature proves that we are currently crowd-sourcing the truth because there are no mechanisms to verify accuracy at scale. I believe blockchains could meaningfully move the needle there.

There could be a point when blockchain native identity enables social networks to verify the legitimacy of the content source. For instance, it is not far-fetched to believe that you could open your phone, conduct a FaceID verification, and sign a piece of content on a social network. In such an instance, the social network won’t have access to the iris scan of the user (like in Worldcoin’s model), but it would have verified the human-ness of the source of the content.

For the technically inclined: The model above is somewhat already in practice. Wallets use a mix of face-id with iCloud storage for private key management. Extending the same to Web3 social networks is within the realm of possibility. I am not suggesting this is a solution or a desirable outcome.

Why does this matter? In the age of endless content, we will need better tools to verify where we get our content from. Anybody can purchase the blue tick on X. Earlier this year, billions of dollars of stock value was wiped off medicine manufacturer Eli Lilly’s market capitalisation when a user tweeted that their insulin would be given off for free.

That may have been a one-off case, but here’s the underlying point: Nobody will be an influencer when even machines can turn into influencers. People would trend towards pieces of content that are produced verifiably by humans. And the internet does not have the infrastructure to do that at scale in a composable fashion. Surely, X and Meta have the budgets needed to do AML/KYC on their hundreds of millions of users. But how would a bootstrapped social network conduct identity checks at scale?

For context, it costs between $4 to $20 to do AML/KYC on an individual using third-party applications. Realistically, a developer would have to spend up to $500k to do AML/KYC on a small user base of just 100k users. It is a good problem, but it is still a barrier to entry that founders would rather not deal with.

Ben Evans recently alluded to this challenge with his piece on intellectual property. He argues that as generative AI comes of age, there will be a new class of copyright infringements. Instead of stealing one piece of content from a publisher, you would teach a generative AI model all the content they publish and create new articles. Who owns the IP rights in such cases?

We are not at a stage where data markets can produce returns for individual users. But there’s a credible case to lay for the following:

Using blockchains to verify the identity of who is posting content

Using the same layer to verify the identity of individuals reusing content

What does that look like? Mirror offers some clues. If you click on a user’s profile in their product, you’ll be able to notice what they have posted in the past. This profile by Livepeer, for instance, even mentions their ENS handle. Applications can use these primitives to accurately verify the provenance of content, much like DeFi applications can verify the source and validity of a token.

I mention this as a use case because it solves a necessity. The internet has already created an environment with more information than what can be consumed. This means the flow of attention would eventually be towards accurate, real, human-generated content.

The tools to verify whether content is human or real don’t exist today. Generative AI is creating problem subsets that can be solved by crypto. It just happens that the influencers on your Twitter feed are not discussing it.

You may think this is far-fetched. But the blurring of lines between the "real world" and what happens on-chain is already happening. RWA (real-world asset) lending uses off-chain reputation as a metric to enable on-chain transactions. You effectively use blockchains as just infrastructure to bring radical transparency into how a debt position is doing and how the capital flows occur. But the business itself happens off-chain. This is similar to how Uber used a different network (the internet) to facilitate offline behaviour (hailing cabs).

It may sound strange to think of these use cases today. It was weird to think of using a mobile device to hail a cab in 2009, using a 256kbps internet connection to bank in 1998, or believing screens and keyboards would upend education. The arc of technology grows exponentially when it taps into human needs. The product may look broken and unusual initially. But that is also where the opportunity subset usually exists for early-stage investors.

Blockchain-native applications have not scaled to hundreds of millions of users because the product category has no regulatory tailwinds yet. The case for scale is the following:

Regulatory landscapes would evolve rapidly

Technology (like AI) would create threats that blockchains can solve

Users would need tools with higher trust and verifiability.

Much like mobile networks and the internet, scale would be a function of technological improvements and use cases improving. To look at FriendTech or Unibot and suggest the industry is headed nowhere is like believing aviation is dead because of the Hindenburg disaster.

The Case for Patient Optimism

During the late 1800s, London was faced with a strange problem. A booming population meant that the city saw an increase in horse-drawn carriages. Some 50,000 horses were transporting people around London, and it was expected that they would soon produce enough dung between them to affect the health of everyone in the region.

Now, you could have lived in that age and believed things were only getting worse – much like some of us within crypto think today. Fortunately, motor vehicles took off within a few decades, and the city didn't drown in dung. Technology saved the day.

Sidenote: There are some reports that the great horse manure crisis was fake news produced by vehicle manufacturers. If the Times had used a blockchain in 1894, we could easily verify the accuracy of the news.

Present-day internet is very similar to London or New York in 1894. Generative AI will fill our feeds and mind-spaces with content we likely don't need. Blockchains are the equivalent of motor cars for this modern problem. But this piece is not about AI. It is about optimism. The reason why one should maintain relative optimism in these environments is quite simple.

Humans process experiences in linear terms.

Technology evolves in exponential terms.

Few things illustrate this trend, as well as Amazon's stock. You could have dismissed the internet as a fad in the early 2000s after the dot-com bubble crashed. Nobody would have thought you were an idiot for a decade – until 2010, when Amazon's stock was right around where it traded in 1999. But you would have ignored that a billion users came online in 2005. You might not have noticed that AWS was now powering Facebook, DropBox and Netflix. You would have even missed this incredible TED talk by Jeff Bezos comparing the internet to electricity.

And in the process, you would have missed out on owning a piece of Amazon as it scaled over the coming decade.

Now, I am nitpicking a stock with the use of hindsight. I was not around in the early 2000s to use these ‘insights’. My point is that it pays off exponentially more to be an optimist than a cynic when it comes to frontier technologies. The markets discount growth in the short run and overvalue possibilities in the long run. This is why inefficient markets exist. The only way to get around it is to be a cynical optimist.

Why cynical? Because markets are also machines that transfer money from the impatient to the patient. Rushing to own a piece of every business could burn your hands, as many VC investors (including myself) learned in the past cycle. The only way to filter is through patient observation and understanding the possibilities a product can enable before the market prices it.

Blockchains are currently in their ‘discount’ phase, which partly makes them the opportunity of a lifetime in disguise.

Off to be in the arena for Bitcoin ETF,

Joel John

If you liked reading this, check these out next: