What's the point?

Are points pointless?

Hey there,

Some notes before we begin..

I updated VCData.site with fundraising details for the past two quarters. If you are a founder looking to raise capital, use the database to map out VCs deploying money into themes you are active in and to get a gauge of the most active investors in the industry. You can also use it to do reference checks on who is leading and who’s busy pretending to lead rounds.

In today’s issue, I explore how crypto-native firms use points to acquire customers. If you are building applications using novel points design mechanisms, drop information about what you are building here. Or reach out through e-mail at joel@decentralised.co.

Markets work in cycles. In March of 2017, when Cosmos had just conducted its $30 million ICO, many thought we were on the cusp of disrupting venture capital. I believed it for a moment, as over the next year, close to $10 billion in capital from retail wallets flowed towards crypto-native startups.

Much of it was from unknowing retail users funding exuberance. By 2019, ICOs had stopped, and VCs were back in power, dominating how much startups would raise and when they could tokenise.

Our industry tends to swing quickly from a buyer’s to a seller’s market. As of this writing, I have had multiple interactions with OTC desks looking to create markets for illiquid SAFTs. Buyers (or sellers) of token investments with long vesting terms try to find liquidity from other investors looking to bet on the price of these illiquid tokens. For a seller (of SAFTs), the upside lies in having immediate dollar liquidity to rotate towards other investments.

A buyer almost always presumes the price of the token will trend higher. In exchange for the risk taken in the trade, buyers of illiquid SAFTs often get a discount.

Founders rarely get to capture any of this value. For legal reasons, if a founder facilitates an open market of illiquid SAFTs, he would be walking into more trouble than he needs to. But what if he could hint at the possibility of receiving tokens to drive user behaviour? Founders have been using the possibility of liquid incentives (airdrops) since at least 2020 (Uniswap) to drive traction on their product.

Over the past few months, a new approach to airdrops has driven activity in Web3 primitives. Points are essentially off-chain IOUs that give a user a relative ranking that helps determine how much they would receive in airdropped tokens. Much like ICOs, they may be yet another ‘phase’ in crypto. Alternatively, they may be here to stay.

In today’s issue, I explain how points came to the market and how they are being used.

The Tease

Looking at the situation in July 2022 may help in understanding the evolution of points. Back then, the NFT landscape was in a lull, and OpenSea had a reasonably well-established monopoly. LooksRare’s threat of providing tokens for NFT trading had gradually declined, and royalties were still used for trading NFTs.

Some may have thought the disruptive forces that would soon change NFT trading forever were far off. However, a few weeks later, a project named Blur launched. Unlike its rival, Blur focused on traders.

In Blur’s first week of operations, it accounted for 0.3% of total NFT trades compared to OpenSea’s 73% and Gem’s 15% (acquired by OS). Today, it accounts for 61.9% of trades done on EVM networks compared to OpenSea’s 34% and Gem’s 1%.

When OpenSea launched, it had to spend two years educating the market about NFTs. OpenSea was trying to build a new market that had not existed. Blur, in contrast, was launched after the NFT market had evolved sufficiently and thus could go after a small subsection of traders responsible for the bulk of the volume in the NFT market.

At the time, there were multiple NFT markets with native tokens, so tokens on their own were not innovative. LooksRare had launched a token and struggled to make a meaningful dent in porting over users from OpenSea.

This is where points enter the picture. Blur’s points system took the concept of a leaderboard from Web2 firms and replicated it for traders. As a trader, you can afford to make short-term losses for long-term gains if you know how many tokens could be received when the airdrop happens. Until then, users did not understand how many tokens could be received for conducting certain activities on a product.

Do you optimise for volume? Should a user spin up multiple wallets because all wallets receive the same number of tokens? Or, do you perhaps pay a lot in fees to the platform to get airdrops? Nobody knew what needed to be done. Giving users points for certain activities helps tweak behaviour towards what platforms want them to do. Too often, the art of the tease with points is in making users conduct multiple actions till they figure what gives the most points.

Points blurred the lines between what a platform expects its users to do and the incentives they receive. In the early days of most point launches, users don’t know how the points would convert to tokens. They only know that a token is set to launch, and the more points they have, the higher the number of tokens they receive.

Points systems are helpful for founders because they accumulate data on user behaviour without committing to a preset date for token launches. A token launch is like a marriage. If it is not working, undoing it takes time and long, messy processes. Points are closer to dates. You can iterate on them till you find one that works.

Launching a token, like marriage, can be costly due to the legal opinions and operational overheads involved. Lawyers, exchanges, and marketing can all take money. Points, on the other hand, can be communicated through Twitter and drive users towards conducting specific actions in a product.

An important caveat must be mentioned here regarding LTV and CAC. Too often, the industry criticises airdrops as a high CAC mechanism for acquiring users. Millions of dollars in tokens may be given to obtain a few thousand users. For instance, the average wallet receiving Uniswap tokens received roughly 400 tokens – these amount to a rough value of $800 when considering the $2 price the token was first listed at.

In contrast, fintech platforms can acquire a user for a few hundred dollars. The primary problem with this contrast is that, unlike VC-backed startups, the VC funds backing the startup do not bear CAC for token ventures. They are borne by markets where liquid assets are traded. The TradFi equivalent of this scenario would be giving stocks to early users of the platform.

I mention this because the assumption that airdrops are a high CAC mechanism to acquire low LTV users is faulty. Venture-backed startups in Web2 have a limited runway. Too often, startups raise exorbitant sums and run loss-leading competitions to acquire market share.

Tokens - as incentive mechanisms, allow early-stage teams to tinker without raising venture dollars as long as their tokens have some value in the liquid markets. Points take this further, as founders can tease tokens and secure user activity today. This is why points are a double-edged sword.

If you tease tokens and don’t launch them early enough, you will get a mercenary group of users that come and leave rather quickly.

But does it matter if revenue was created in the process? Friend.tech offers some clues.

Note: In the bits below, I presume Friend.tech has no token as it has not been announced yet. They may release one in the coming months.

When Friend.tech launched, the assumption was that it would disrupt Web3 social networks because creators needed a new mechanism to monetise their presence. But a month later, the volume of assets traded on the product rapidly declined. The poorly designed points system was partially responsible. Users believed that accruing points would translate to tokens eventually. When the tokens were not released in a timely fashion, users flocked elsewhere.

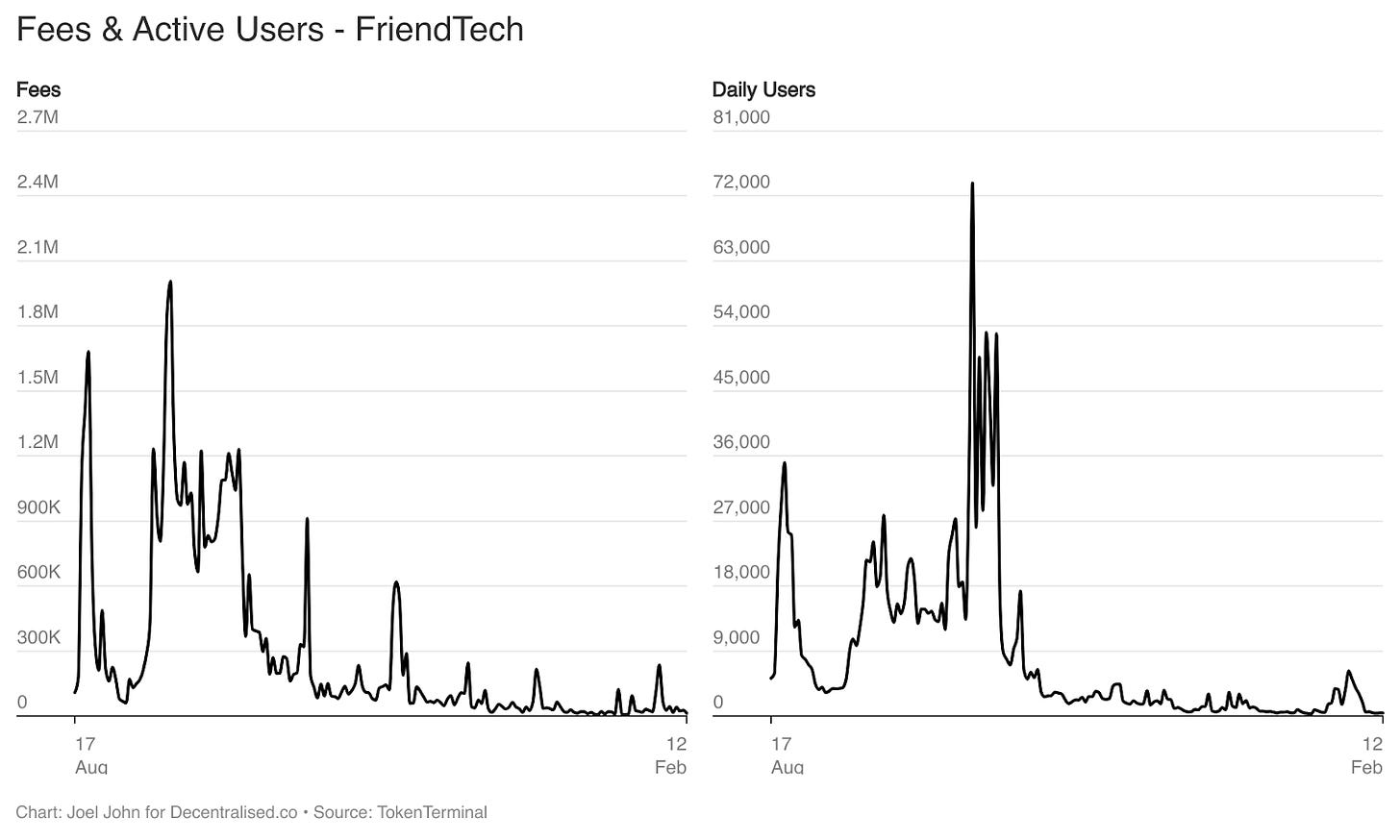

As the chart above shows, user attention is short-lived. Revenue on Friend.tech has collapsed from over a million daily to under $20k each day as of writing this.

What I find pretty telling about the trend is that the TVL on Friend.tech has not declined despite the lack of user activity. Users that ported assets to Base (the chain Friend.tech used) left their capital on the product long after stopping trading. At its peak, the TVL on the product was close to $50 million. As of writing this, it is close to $25 million. Friend.tech has not launched a token over the past few months, and users have flocked elsewhere. But does it matter?

The product generated some $27 million in fees in months. Much like many fond memories, Friend.tech could be part of an application where we remember, and say - ‘It was good while it lasted.’

The markets presumed there would eventually be tokens. That is what we saw with Blur. But in Friend.tech never releasing one, the platform could pocket $27 million in fees instead of passing the money on to a DAO.

Some proponents would argue that in Friend.tech’s case, it designed short-term games that tap into the virality of existing social graphs for fun and profit.

The problem is that such an approach may work once in a while. If everyone thinks a token will not be launched, nobody will rush into a new product

Launching a good points-based system is predicated mainly on the fine art of the tease. It is the token before the token – the rallying cry circulating among users from far and wide in hopes of eventually receiving tokens.

In the hands of a resourceful founder, it is a tool, like many others, that can be used to understand user behaviour and source initial user & token liquidity. A well-designed and useful product can sustain a points system without launching a token. But the inverse is also true. A weak product without a token can be a one-way ticket to a community feeling burned by founders.

Vampire Attacks & Retention

One category to be observed for point usage is that of wallets. Due to its association with Consensys, MetaMask has been the go-to product for most users, interfacing with Ethereum and EVM-based networks. Over the past few months, we have seen a gradual shift to alternative wallets.

Currently, most wallets differentiate themselves in one of two ways:

Some interfaces aggregate and verify unique experiences, intending to become a super-app similar to WeChat. Some even surface on-chain content to retain users. Timeless Wallet fits this description well today.

Others create social networks atop wallet-linked identities that help users coordinate capital and attention towards emergent primitives. In these instances, being able to verify users’ assets from their wallets becomes an added verification layer. The most prominent among this crop of wallets (or portfolio managers) today is DeBank.

Emergent competitors focused primarily on better interfaces and critical management solutions have historically struggled to build a footing, but that has changed in the past six months. Rainbow Wallet and Rabby have launched what can be considered vampire attacks:

If a Metamask user ports over their wallet to Rabby or Rainbow, they receive extra points. It incentivises users to port over their keys to Rabby’s wallet.

Why does this matter? As of this writing, Metamask dominates the wallet landscape. According to Subinium on Dune Analytics, Metamask is home to 64% of active wallets on any given day. The two largest wallets – Okx and Bitget – benefit tremendously from the distribution of the exchanges behind them but have only 16% of the share on any given week.

In comparison, Rainbow or Zerion, which don’t benefit from large distribution outlets, are at 4–5% of the market’s share.

Rainbow’s launch of their wallet product has meaningfully impacted their growth. Consider the graph below tracking the product revenue for a sense of scale. A month before their points system’s launch, swaps on Rainbow Wallet made $47k in revenue off $5.4 million in volume. That figure was at $900k off in December, close to $100 million in volume in a month. That is a 20x jump but unlikely to stick unless a token follows suit soon enough.

One way to benchmark this growth is to compare MAUs with Metamask's. According to data from TokenTerminal, Metamask has about 300k active users in any given month. In comparison, Rainbow has around 30k. So, despite their points tease and a potential token launch down the road, they have not been able to port a huge chunk of users from Metamask to Rainbow. Familiarity and history matter more to users here than points and marginal utility.

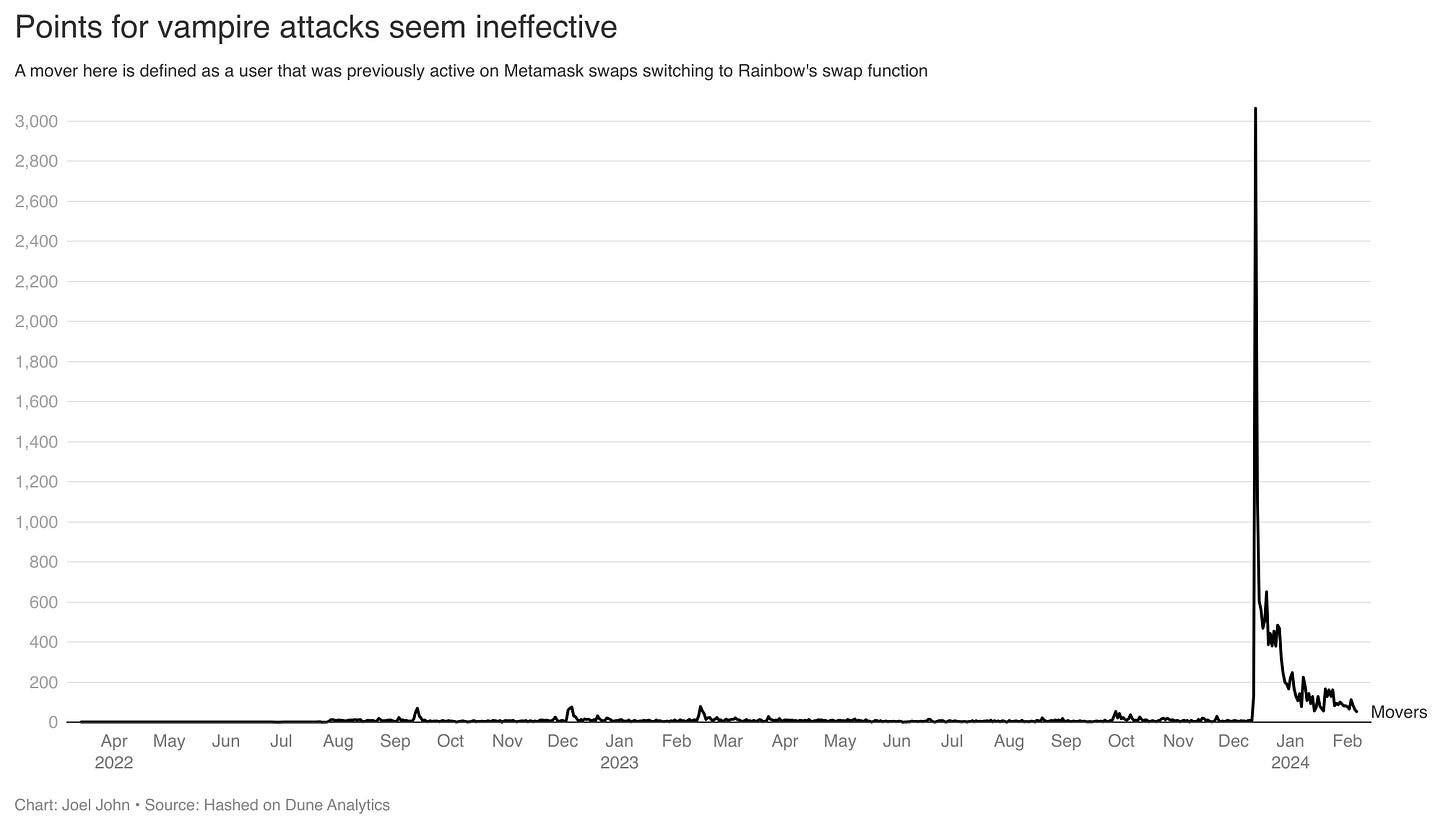

As a matter of fact, the number of users porting from Metamask to Rabby has been quite small. It peaked at 3000 users the day the points system was announced. It has since declined to under 100 users on any given day. In other words, the launch of the points system has not had a material impact on drawing users over from Metamask.

Does that mean it was a futile attempt?

Not really. As mentioned earlier, these metrics must be examined in the context of the product’s usage prior to the points launch. In the case of Rainbow Wallet, a tenfold increase in the number of monthly users was observed. So, even though they may be far from taking over a non-tokenised incumbent, they have acquired users at a fraction of the cost they would have incurred had they opted for a more traditional route.

For context, the average user on Metamask had a volume of close to $1k on any given day last month. The CAC for such users (individually) can be extremely high if targeted through more traditional mediums.

Tensor tried a similar approach to points last year. Instead of incentivising users to continue to use the platform, they punished users who tried using a different NFT platform. On top of that, they also incentivised trading specific NFTs that were crucial to the Solana ecosystem.

This yielded two forms of behaviour. Firstly, users loyal to Tensor had an edge over users farming for points across products. Secondly, communities like Madlads were more closely aligned with Tensor’s success.

Among tribes of ages past, it used to be common to extend warm invitations to potential allies through feasts and ceremonial honours. In the modern age, we offer points. But will these tribes stick around? Are they value additive? One place that offers clues is Blast.

In November 2023, Blur launched an L2 called Blast. When they first launched the product, two catalysts helped propel it to prominence. Firstly, they were being launched by Blur – an existing token with a user base of power users for NFT marketplaces. Secondly, they teased a points programme, which helped propel users to employ the protocol in a matter of hours. Some 25,000 wallets were active on the first day.

As of this moment, that number is down to 1,500. By any standard, that seems to be a disaster, as there is more than a 90% drop-off in active users. Part of the reason could be that Blast’s chain is not yet live. Most users may be coming to park capital and leave.

But the metric connected to it – the total value locked – has evolved from a measly $81 million to over $1.4 billion. Remember that Blast has not spent a dime to get that TVL in their network. They have only offered teaser points, which will convert to tokens in the future. The capital locked in the network can be a crucial source of liquidity as Blast rolls out protocol-specific applications like lending or NFT-related perpetual or spot markets that function at a fraction of the fees.

In essence, these teaser points have helped Blast gain liquidity for its protocol without capital expenditures.

Does that liquidity in itself have value? I think it does, as long as the applications that use the aforementioned liquidity are released alongside the tokens. It would be comparatively easy for Blast to do this as it has a functional application (Blur). Blast could use the network and its tokens once it goes live. In essence, the protocol is to take a full-stack approach. Blast owns the core application (Blur), the users (through the network), and the underlying protocol. Eventually, it could optimise operations to be the go-to protocol for all NFT functions, much like Flow attempted to do in 2021.

What’s The Point?

Points will become a crucial instrument for launching new products and testing for PMF. Unlike ICOs, they are here to stay, as they facilitate customer acquisition and bootstrapping liquidity early on at a fraction of the cost vs spending raised dollars. We will, however, see a crop of products that ‘test’ their token hypothesis using points and never issue tokens, inevitably burning users and leading to consumer apathy for many points programmes.

Teams will soon realise that for transactional products like swap interfaces (wallets) or trading platforms (Friend.tech), teasing points that may convert to tokens can lead to millions of dollars in revenue.

Would you really want to launch a token if you made $50 million in fees in a single quarter? I am not sure I would quite know the answer until I saw this in my smart contract. This is subjective. Some founders would sense the need to launch a network and make their millions by eventually selling tokens. Much like many NFT teams monetised through royalties, others would simply sit on the fees and not launch tokens. This leads me to my next point.

When it comes to points, the most prominent element that indicates clear value capture is the presence of fees. If a user is spending real money to get hypothetical tokens whose valuation or supply is unknown, it shows some form of demand. Products capable of capturing fees at scale from users and building their treasury are in an excellent place to use points. Rabby wallet and Tensor fall into this category.

The next category is usually products that can use idle capital in some form. Blast’s TVL and marginfi (a lending product on Solana) come to mind here. In both instances, the CAC of getting idle deposits is drastically reduced through the existence of a points programme.

Where points programmes fail miserably, however, is with content platforms. If you offer users points for creating content, it turns into spam. If you incentivise silent lurking, it makes a lack of incentives for creators to engage. If you incentivise engagement, it leads to a lack of signal. You get the point. Social networks can seldom be scaled through a points product alone, purely because it is hard to quantify the economic value of social interaction on a platform like Twitter or Farcaster.

While writing this article, I wondered if points programmes lead to lasting retention. One of the clearest instances I could find data for was from OpenSea, LooksRare, and Blur, all category leaders (at some point in time) for NFTs, which were historically a transactional product. Specifically, I looked at numbers from January 2023, a unique time when Blur’s token went live, LooksRare’s had been live for a year, and OpenSea was still a category leader.

To benchmark whether the existence of tokens/points helped, I looked at metrics from T+3 months. That is, what portion of a cohort of users on a product today, may continue to use the product three months out. This sought to determine what percentage of a user base signing up today would stick around three months later. TokenTerminal has this data available if you’d like to dig deeper into it.

For OpenSea, of a cohort of 92k users in January 2023, only about 11% were active three months later. That might seem terrible until you consider how things played out for LooksRare. Of a cohort of 3500 users active that January, only about 1% of the user base was active three months later. One caveat here is that in January 2022, when LooksRare’s token was trending, the retention figure after three months was as high as 16.5%, and their user base was at 30k.

In contrast, Blur, who had a token and an existing points programme, had a user base of 25k and a retention rate of 20% after three months (compared to OpenSea’s 11% and LooksRare’s 1%). If we return to October 2022, when Blur’s token was not yet live, the retention rate after three months was as high as 44% (although that period overlaps with the token launch).

Please excuse the vomiting of numbers in the paragraph above, but the point stands: Combining points and tokens results in users sticking around longer. And in an age where everybody has the attention span of a goldfish, knowing how to tease incentives and release them at the right time can determine a product’s relevance or death as yet another VC darling that never delivered. (There are too many VC darlings in the graveyard of startups.)

Centrally managed points programmes are very similar to airline points: A developer can devalue them at will. The primary difference is that where an airline has complex machinery and a network of hubs to deliver travellers, most dApps are bundles of smart contracts. They have little to lose if, for whatever reason, they decide not to issue tokens. This is the risk most community members expose themselves to. But if the numbers point to anything, it appears as though people are comfortable with that risk for now.

Sid describes points as honey that attracts human attention like flies to products. Surely, most users that come with such programs are unlikely to stick around for the long run. But it gives products a better alternative than spending advertisement dollars when it comes to being discovered.

Learning how to make iced V60 coffee,

Joel John

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

Read this in Arthur Hayes' article - points program will power the best-performing tokens of this cycle, and that conclusion stands truer after reading this!

Crypto has figured a way to crash the CAC relative to web2 counterparts, complemented with transparent points-program - this can usher into the new phase of building products and testing PMF.

There should be a fine balance b/w token launch and points launch otherwise it results into just user apathy and eventually, distrust towards points which might make fate for such programs similar to ICO, liquidity mining.