Mergers & Acquisitions

The build vs buy conundrum

Hello!

Over the past six weeks, we have written about the state of revenue, venture capital and network effects in crypto VC.

Today, we look at what is happening with mergers and acquisitions. If the pool of firms with IPO-worthy revenue is low, and the amount of venture capital is in decline, then we are probably primed for mergers and acquisitions season. But how much money exists in that pool? Who are the people leading that charge? And why are they even buying companies?

We have been thinking about these questions and using data to aid our assumptions.

Today’s story is what came of it.

We try to explain why a founder should consider a merger or an acquisition as a pathway to returning capital or opening a new chapter. It is an economic roadmap for how we consider the industry will evolve in the next 18 months.

The article below is a brief thesis of what guides our own decisions. We have been in the process of acquiring businesses & helping portfolio founders with their mergers. The story today is backed by our own experiences of being in the market on both the buying and selling sides.

If you are a founder considering a merger or an acquisition, drop us us a note at venture@decentralised.co. We have been building an M&A advisory division within Decentralised.co. This is first in a series of articles exploring the theme.

On to the story now..

Joel

Hey there!

Coinbase just acquired Deribit for $2.9 billion. It is the largest M&A event in crypto history. It appears, history rhymes in technology too.

Google has acquired 261 companies until now. Some of the acquisitions have led to products like Google Maps, Google AdSense, and Google Analytics. Perhaps the most significant was acquiring YouTube for $1.65 billion in 2006. In Q1 2025, YouTube generated $8.9 billion in revenue, 10% of Alphabet’s total revenue. Similar to Google, Meta has made 101 acquisitions to date. Instagram, WhatsApp, and Oculus are standout examples. Instagram generated over $65 billion in annual revenue, representing over 40% of Meta's entire business in 2024.

Crypto is no longer a new industry. Some estimates put the number of crypto users at 659 million. Coinbase has over 105 million users. The estimated number of internet users is 5.5 billion. So, crypto is ~10% of the total internet users. These numbers are important because they help us determine where the next leg of growth comes from.

An increase in the number of users is an obvious way to grow. For now, we have only cracked financial use cases for crypto. As other applications use blockchain rails for infrastructure, the overall pie will grow. Acquiring existing users, cross-selling, and increasing the per-user revenue are some of the ways for existing companies to grow.

When the pendulum swings towards buy

Acquisitions solve three critical problems that mere fundraising cannot. First, they enable talent acquisition in a highly specialised field where experienced developers remain scarce. Second, they facilitate user acquisition in an environment where organic growth has proven increasingly costly. Third, they allow for technology consolidation, enabling protocols to extend beyond their original use cases. I will explore more of this in later sections, along with examples from the industry.

We are in the middle of a new M&A wave in crypto. Coinbase is going to acquire Deribit for a record $2.9 billion. Kraken is acquiring NinjaTrader, a CFTC-regulated retail futures trading platform in the US, for $1.5 billion. Ripple is going to acquire Hidden Road, a multi-asset prime broker, for $1.25 billion. It also made an offer to buy Circle, which was rejected.

Each of these deals reflects the evolving priorities of the space. Ripple wants distribution and regulated rails. Coinbase is chasing options volume. Kraken is filling product gaps. These acquisitions are rooted in strategy, survival, and competitive positioning.

The table below can help you peek into an incumbent’s mind as to how they think about buy vs build.

While the table summarises key trade-offs in build vs. buy decisions, incumbents often rely on proprietary signals to act decisively. A good example is Stripe’s acquisition of Nigeria’s Paystack in 2020. Building its own infrastructure in Africa would mean steep learning curves around regulatory nuances, local integration, and merchant onboarding.

Stripe chose to buy instead. Paystack had already solved for local compliance, built a merchant base, and proven distribution. Stripe’s acquisition checked off multiple boxes like speed (first-mover advantage in a growing market), capability gap (local expertise), and competitive threat (Paystack becoming a regional rival). The move fast-tracked Stripe’s global ambitions without diluting focus from its core.

Before we unpack the mechanics of why deals happen, it's worth asking 1) why a founder should think of being acquired, and 2) why now is a particularly important time to think about it.

Why does the macro environment favour acquisitions now?

For some, it's about exit liquidity. For others, it’s about plugging into a more durable distribution channel, securing long-term runway, or being part of a platform that magnifies impact. And for many, it's a way to avoid the increasingly narrow path of venture funding, where capital is scarcer than ever before, expectations are higher, and timelines can be unforgiving.

The Rising Tide won’t raise all boats

Venture markets lag liquid markets by a few quarters. Typically, whenever BTC peaks, it takes a few months or quarters for venture activity to dampen. Venture funding for crypto has declined by over 70% from its 2021 peak, with median valuations returning to 2019-20 levels. I don’t think this is a temporary pullback.

Let me explain why. In short, VC returns have declined, and the cost of capital1 has increased. So, due to higher opportunity cost, fewer VC dollars are chasing deals. But the crypto-specific reason is that the market structure is affected by the massive rise in the number of assets. I keep going back to this chart, but most token businesses need to realise this. Creating new tokens just because it is easy may not be a sound strategy. Capital is limited on the internet. With each marginal new asset issued, the amount of liquidity chasing it reduces, as the chart below shows.

Every VC-funded token that is launched with a high FDV needs massive liquidity to go to a several-billion-dollar market capitalisation. For example, EigenLayer’s EIGEN launched at $3.9 with the FDV of $6.5 billion. The float was ~11% at the time of launch, making the market cap ~$720 million. The current float is ~15%, and the FDV is ~$1.4 billion. Due to various types of unlocks, 4% of the supply has been unlocked since the token debuted. The token is down ~80% since launch. The price needs to increase by 400% with a rising supply to get back to its launch valuation.

Unless the token actually accrues value, there’s no reason for market participants to bid for these tokens, especially in a market that has abundant options to place their bets. All these tokens will very likely never see those valuations again. I looked at 30D revenue of all the projects on Token Terminal, there are three projects (Tether, Tron, and Circle) with more than $1 million monthly revenue. And only 14 with monthly revenue higher than $100k. Out of the 14, eight have a token, i.e., are investible.

This means that private investors either cannot exit or will have to exit at some discount. Poor secondary market performance across the board puts pressure on the ROI of VC dollars. This will result in a more cautious approach to investing. So either the product will have to find PMF, or it has to be something that we haven’t tried yet to get investors interested in it and fetch a premium on the valuation. But a product with just an MVP and no users will have a tough time finding investors. So if you are building yet another “blockchain scaling layer”, chances are you won’t get good investors.

We are already seeing this happen. As mentioned in our Venture Funding Tracker article, monthly venture capital inflow into crypto dropped from the 2022 peak of $23 billion to $6 billion in 2024. The total number of rounds declined from 941 in Q1 2022 to 182 in Q1 2025, indicating the cautiousness of VC dollars.

Why now?

So what happens then? Acquisitions will probably make more sense than fresh funding rounds. Protocols or businesses that are making some revenue will go after niches that address their blind spots. The current environment is pushing teams toward consolidation. Higher interest rates have made capital expensive. Adoption has plateaued, so organic growth is harder to come by. Token incentives are less effective than they once were. Meanwhile, regulation is forcing teams to professionalise faster. All of this has pushed crypto towards acquisitions as a means to grow. This time, crypto M&A activity seems more deliberate, more concentrated, and far more calculated than in previous cycles. We will see why in the later sections.

Acquisition Cycles

Historically, traditional finance has seen five to six major waves of M&A, triggered by factors like deregulation, economic expansion, cheap capital, or technological shifts. Early waves were driven by vertical integration and monopolistic ambition; later waves emphasised synergy, diversification, or global reach. Rather than walking through every chapter of that century‑long playbook, the lesson is simple: consolidation accelerates whenever growth slows and money is abundant.

What explains these distinct phases of crypto acquisitions? It’s a similar playbook we’ve seen across decades of traditional markets. Emerging sectors often grow in waves instead of straight lines. And each wave of M&A reflects a different need in the maturity curve—from building product, to finding PMF, to capturing users, to locking in distribution, compliance, or defensibility.

We saw this with the early internet, during the mobile OS era. Think back to mid-2005, when Google bought Android. It was making a strategic bet that mobile would become the dominant computing layer. According to Androids: The Team That Built the Android Operating System, a book by Chet Haase, who was a long-time engineer at Android and Google.

In 2004, there were 178 million shipments of PCs worldwide. During the same period, there were 675 million phones shipped; nearly four times as many units as PCs, but with processors and memory that were as capable as PCs were in 1998.

The mobile OS landscape was fragmented and restricted. Microsoft charged licensing fees for Windows Mobile, Symbian was primarily Nokia's domain, and BlackBerry's OS was exclusive to its own devices. This created a strategic opening for an open platform approach.

Google seized this opportunity by acquiring a free, open-source operating system that manufacturers could adopt without expensive licensing fees or the burden of building their own OS from scratch. This democratised approach allowed hardware makers to focus on their strengths while accessing a sophisticated platform that could compete with Apple's tightly controlled iOS ecosystem. Google could’ve built an OS from scratch, but buying Android gave it a running start and helped counter Apple’s growing dominance. Twenty years later, 63% of the web traffic is from mobile devices. 70% of the mobile web traffic is through Android. Google spotted the move from PCs to mobile. The Android acquisition helped Google dominate the mobile search, too.

The 2010s era was dominated by cloud infrastructure related deals. Microsoft’s $26 billion acquisition of LinkedIn (2016) was a move to integrate identity and professional data across Office, Azure, and Dynamics. Amazon acquired Annapurna Labs (2015) to build its own custom chips and edge compute capabilities for AWS, signalling how vertical integration in infra was becoming key.

These cycles happen because each stage of an industry’s evolution brings different constraints. Early on, it’s speed to product. Later, it’s access to users. Eventually, it’s regulatory clarity, scalability, and staying power. Acquisitions are how winners compress time by buying licences instead of applying for them, buying teams instead of hiring, buying infrastructure instead of building from scratch.

So yes, crypto's M&A rhythm does echo what happened in traditional markets. Different technologies, same common sense.

Crypto’s three M&A waves

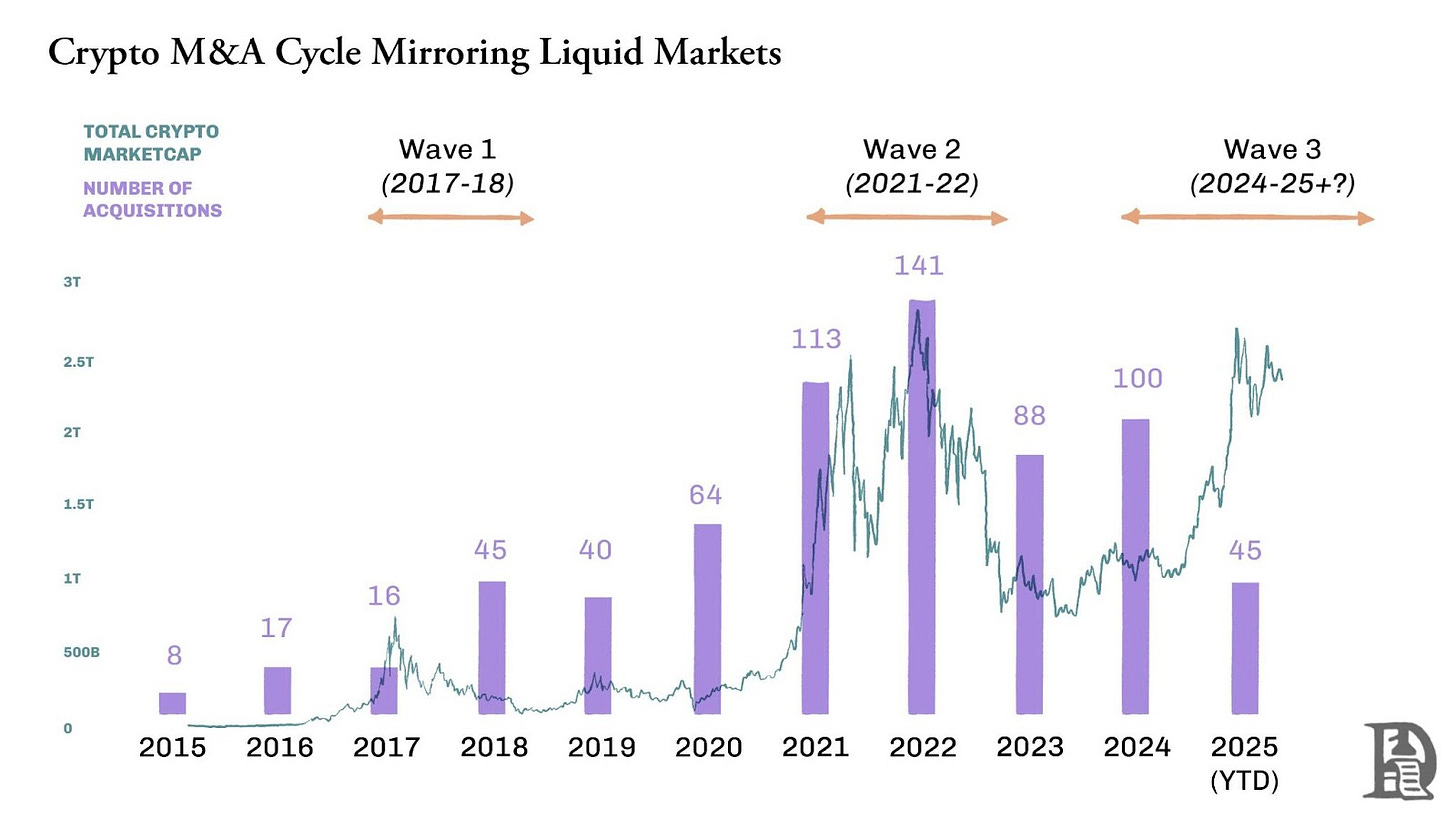

If you think of it, crypto M&As have undergone three distinct phases. Each of them was marked by what the market needed and where the technology was at the time.

Wave 1 (2017–2018) – The ICO Roll‑Up: Smart contract platforms were new. There was no DeFi, only the hope of building on-chain applications that would have users. Exchanges and wallets bought smaller front‑ends to capture new token holders. Notable deals in this era were Binance buying Trust Wallet and Coinbase’s acquisition of Earn.com.

Wave 2 (2020–2022) – Treasury‑Fuelled Acquisitions: Some protocols like Uniswap, Matic (now Polygon), and Yearn Finance and businesses like Binance, FTX, and Coinbase had tasted PMF. Their market capitalisations had soared during the 2021 bull run, and they had tokens with overextended valuations to spend. Protocol DAOs used these governance tokens to acquire adjacent teams and tech.

Yearn’s merger season, OpenSea acquiring Dharma, and FTX’s pre‑collapse spree (LedgerX, Liquid) defined the era. Polygon also went on an ambitious acquisition spree, buying teams like Hermez (zk rollups) and Mir (zk tech) to position itself as a leader in zero-knowledge scaling.Wave 3 (2024– 2025+) – The Compliance & Scalability Phase: With venture funding tight and regulation clearer, cash‑rich incumbents are snapping up teams that bring regulated venues, payments infra, zk talent and account‑abstraction primitives. Recent examples include Coinbase acquiring BRD Wallet to strengthen its mobile wallet strategy and user onboarding. It also acquired FairX to accelerate its push into derivatives.

Robinhood’s acquisition of Bitstamp was aimed at expanding into other geographies. Bitstamp had over 50 active licenses and registrations globally and will bring in customers across the EU, UK, US, and Asia. Stripe's acquisition of OpenNode to deepen its crypto payments infrastructure. Expect mid‑nine‑figure, token‑plus‑equity hybrids, and PE‑style roll‑ups of compliance oracles and staking infra.

Why do acquirers buy?

Some startups get acquired over others due to a handful of strategic motivations. When a buyer initiates a deal, they are typically looking to accelerate their roadmap, neutralise a competitive threat, or expand into new user bases, technologies, or geographies.

For founders, becoming an acquisition target is more than just the payday. It’s about achieving scale and continuity. A well-structured acquisition can give teams greater distribution, long-term resourcing, and the ability to see their product integrated into the broader ecosystem they set out to improve. Rather than grinding out another fundraising round or pivoting to catch the next wave, being an acquisition target can be the most efficient way to realise the startup’s original mission.

Here’s a framework to help you assess how close your startup is to being "target-ready." Whether you’re actively considering an acquisition path or simply want to build with optionality in mind, doing well on these parameters will dramatically increase your likelihood of being noticed by the right acquirer.

The Four Models of Crypto Acquisitions

As I've studied the major deals of the past few years, clear patterns have emerged in how these acquisitions are structured and executed. Each represents a different strategic imperative:

1. Talent Acquisition

Yes, vibe coding has become a thing, but teams need skilled coders who know how to build things without AI. We are not at a point where you can tell AI to code something and trust that code with millions of dollars. So, acquiring small startups for talent before they become a threat is indeed a genuine reason for incumbents to acquire startups.

But why do acquihires make logical sense economically? First, the acquiring company often gets associated intellectual property (IP), ongoing product lines, and an existing user base or distribution channel along with the talent. For example, when ConsenSys acquired Truffle Suite in 2020, it not only absorbed a developer tools team but also secured critical IP, such as Truffle's suite of developer tools, including Truffle Boxes, Ganache, and Drizzle.

Second, acquihires allow incumbents to aggregate specialised teams quickly, often at a lower blended cost than assembling one from scratch in competitive talent markets. I know anecdotally that there were barely 500 engineers who really understood the ZK tech back in 2021. This is why Polygon’s acquisition of Mir Protocol for $400M and Hermez Network for $250M in MATIC tokens probably made sense. Hiring that calibre of zero-knowledge cryptographers individually would’ve taken years, assuming even availability.

Instead, the acquisition bundled elite ZK researchers and engineers into Polygon’s team overnight, streamlining both hiring and onboarding at scale. This bundled cost of acquisition, when benchmarked against recruiting, training, and ramp-up time, can be economically efficient, especially when the acquired teams are already shipping products.

When Coinbase acquired Agara in late 2021 for a reported $40–50 million, the deal was less about customer service automation and more about engineering talent. Agara’s team, based in India, had deep expertise in artificial intelligence and natural language processing. Post-acquisition, many of these engineers were integrated into Coinbase’s product and machine learning teams to support its broader AI ambitions.

Although the acquisitions were framed around technology, the real asset was the talent: engineers, cryptographers, and protocol designers who could build Polygon's vision for a ZK future. While the full integration and productisation of these teams' work has taken longer than anticipated, the acquisitions positioned Polygon with one of the deepest in-house ZK benches in the industry, a resource that continues to shape its competitive strategy to this day.

2. The Capability/Ecosystem Expansion

Some of the most strategic acquisitions focus on expanding either ecosystem reach or internal capabilities. This is often helped by the acquiring firm's positioning and market visibility.

Coinbase is an excellent example of expanding capabilities through acquisitions. It acquired Xapo in 2019 to expand its custody business. This laid the foundation for Coinbase Custody, enabling secure, compliant storage solutions for digital assets. In 2020, acquiring Tagomi, a prime brokerage platform, led to the creation of Coinbase Prime, a comprehensive suite for institutional trading and custody. The acquisition of FairX in 2022 and Deribit in 2025 will help Coinbase solidify its position in derivatives in the US and globally, respectively.

Consider Jupiter's acquisition of Drip Haus in early 2025. Jupiter, the leading DEX aggregator on Solana, aimed to expand beyond DeFi into NFTs. Drip Haus had carved out a niche by enabling creators to distribute free NFT collectables on Solana, building one of the most engaged on-chain audiences in the ecosystem.

Because of Jupiter's proximity to Solana's infrastructure and developer ecosystem, it had unique insight into which cultural products were gaining traction. It saw Drip Haus emerge as a key attention hub, particularly among creator communities.

By acquiring Drip Haus, Jupiter gained a foothold in creator economies and community-driven NFT distribution. The move enabled it to extend NFT capabilities to a broader audience and integrate NFTs as incentives for traders and liquidity providers. It wasn't just about collectibles, though. It was also about owning the NFT rail for Solana-native attention. This ecosystem expansion marked Jupiter’s first step into culture and content, a vertical where it had no prior presence. This was very much like how Coinbase used acquisitions to systematically build capabilities across custody, prime brokerage, derivatives, and asset management.

Another example is FalconX’s acquisition of Arbelos Markets in April 2025. Arbelos was a specialised trading firm known for its expertise in structured derivatives and risk warehousing. These capabilities are critical to serving institutional clients. FalconX, with its position as a prime broker and aggregator for institutional crypto flows, had visibility into how much derivative volume was flowing through Arbelos. This probably gave it the conviction that Arbelos was a high-impact acquisition target.

By bringing Arbelos in-house, FalconX strengthened its ability to price, hedge, and manage risk across complex crypto instruments. The acquisition will help them upgrade core infrastructure to attract and retain sophisticated institutional flows.

3. The Infrastructure Distribution Play

Beyond talent, ecosystems, or users, some acquisitions are about infrastructure distribution. They embed one product into a broader stack to improve defensibility and reach. A clear example is ConsenSys' acquisition of MyCrypto in 2021. While MetaMask was already the leading Ethereum wallet, MyCrypto brought UX experimentation, security tooling, and a different user segment focused on power users and long-tail assets.

Rather than a full rebrand or merger, the teams continued developing in parallel. And they eventually folded MyCrypto’s feature set into MetaMask’s codebase. This strengthened MetaMask’s market position and helped stave off competition from more agile wallets by absorbing innovation directly.

These infrastructure-driven acquisitions aim to lock in users at a critical layer by improving the tooling stack and defending distribution.

4. The User Base Acquisition

Finally, there's the most straightforward strategy: buying users. This is particularly evident in the NFT marketplace wars, where competition for collectors has grown fierce.

OpenSea acquired Gem in April 2022. At the time, Gem was serving ~15 000 weekly active wallets. For OpenSea, the deal was a pre‑emptive defence: lock in the highest‑value “pro” cohort and accelerate development of an advanced aggregator interface that later launched as OpenSea Pro. Acquisitions can be more cost-effective in competitive markets where speed is critical. The lifetime value (LTV) of these users, especially "pro" users in the NFT space who often spend significant amounts, likely justifies the acquisition cost.

Acquisitions like this make sense when the math lines up. The average revenue per NFT user in 2024 was $162, according to industry benchmarks. But power users, Gem’s core demographic, likely contributed orders of magnitude more. If even a conservative estimate pegs their LTV at $10,000 each, that implies $150 million in user value. If OpenSea bought Gem for less than $150 million, the acquisition likely paid for itself in user economics alone, even before factoring in saved development time and brand alignment.

Though less headline‑grabbing than talent‑ or tech‑driven deals, user‑centric acquisitions (and equivalents) remain one of the quickest ways to cement network effects.

What do the numbers say?

Here’s a macro lens on how crypto acquisitions have evolved over the past decade—by volume, by buyer, and by target category.

As mentioned earlier, the deal volume doesn’t move in perfect sync with price action in public markets. In the 2017 cycle, Bitcoin peaked in December, but the acquisition wave was alive even in 2018. The same lag appeared this time. BTC topped out in November 2021, but crypto M&A didn’t peak until 2022. Private markets take longer to react than liquid ones, often digesting trends on a delay.

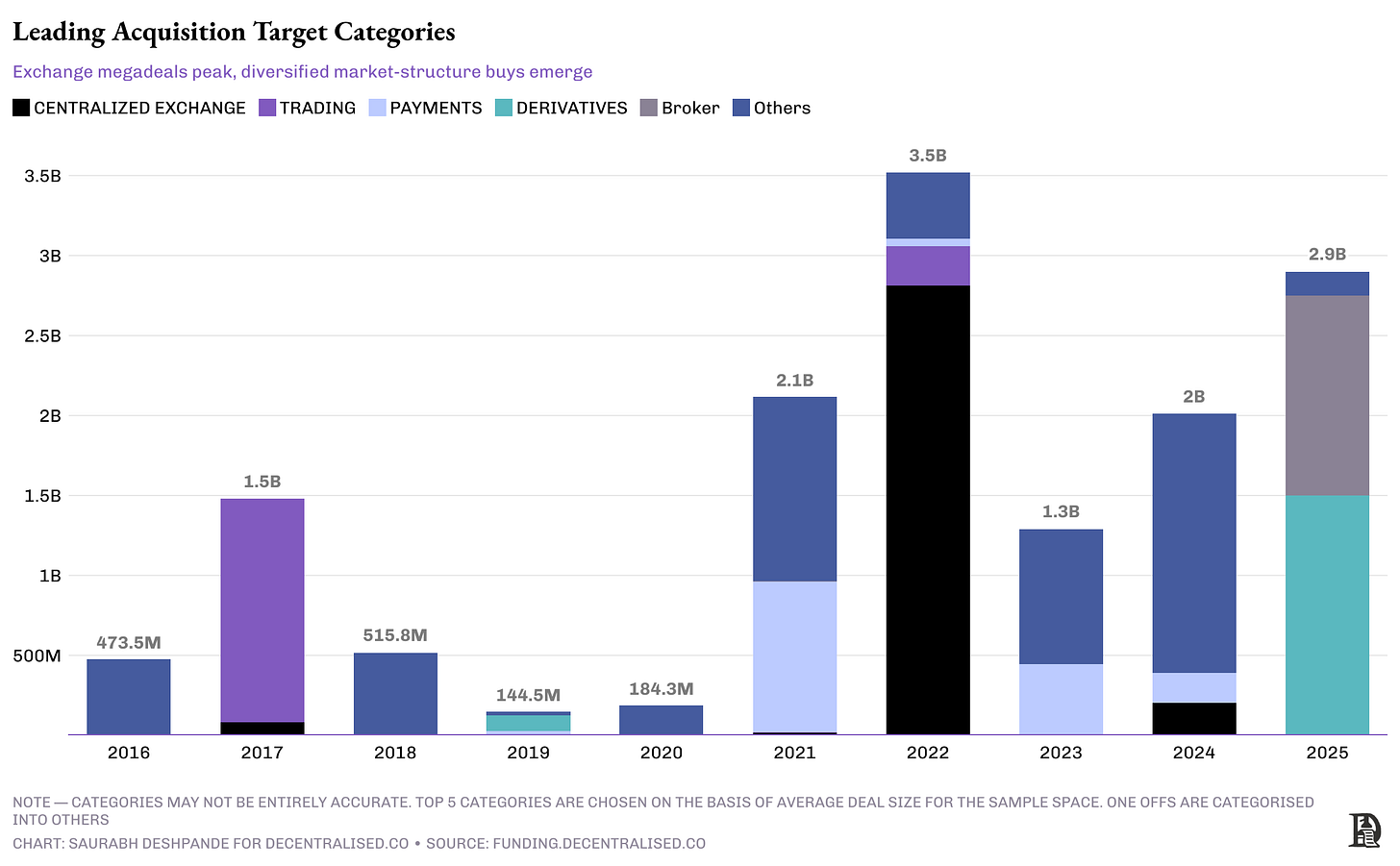

Acquisitions ramped aggressively after 2020, with 2022 marking the peak in both count and cumulative value. But volume isn’t the whole story. While activity cooled in 2023, the size and nature of acquisitions shifted. The days of broad, defensive buying sprees gave way to more deliberate category bets. Interestingly, while the number of acquisitions declined after 2022, aggregate deal value rebounded in 2025. That suggests a market not shrinking, but that maturing buyers are doing fewer, bigger, and more targeted deals. The average deal size increased from $25 million in 2022 to $64 million in 2025.

On the target side, the early years were scattered. Marketplaces picked up gaming assets, rollup infra, and a range of ecosystem bets spanning early-stage gaming, Layer 2 infrastructure, and wallet integrations. But over time, target categories became more focused. The 2022 peak saw a concentration of deals focused on acquiring trading infrastructure such as matching engines, custody systems, and front-end interfaces needed to launch or enhance exchange platforms. More recently, acquisitions have concentrated around derivatives and user-facing broker rails.

Zooming in on 2024‑25 transactions shows emerging concentration. Derivatives venues, broker rails and stablecoin issuers now absorb more than 75 % of disclosed deal value. Clearer CFTC rules on crypto futures2, MiCA’s passport for stablecoins3, and Basel‑lite guidance4 for reserve assets have de‑risked these verticals. Heavyweights such as Coinbase responded by buying regulatory footholds rather than building them. NinjaTrader gives Krakenall the necessary licenses, along with 2 million customers in the US. Bitstamp gives MiCA‑ready exchange coverage, while OpenNode plugs USD‑stable rails straight into Stripe’s merchant network.

Buyers evolved too. In 2021–22, exchanges led the charge by acquiring infrastructure, wallets, and liquidity layers to defend market share. By 2023–24, the baton had passed to payment companies and financial tooling platforms, targeting downstream products like NFT rails, brokers, and structured product infrastructure. But with changing regulations and an underserved derivatives market, exchanges like Coinbase and Robinhood are making a comeback as acquirers and scooping up derivatives and brokerage infrastructure.

A common thread among these acquirers is that they are cash-rich. At the end of 2024, Coinbase had over $9 billion worth of cash and cash equivalents. Kraken made $454 million in operating profit in 2024. Stripe had over $2 billion in free cash flow in 2024. The bulk of the acquirers by deal value are profitable businesses. Kraken's NinjaTrader purchase to control the full futures trading stack from UI to settlement. This is an example of vertical acquisition, which aims to control more of the value chain. Horizontal acquisitions, by contrast, expand market reach within the same layer, exemplified by Robinhood's Bitstamp acquisition to extend geographic coverage. Stripe's acquisition of OpenNode combined vertical integration (adding crypto capabilities to its payment stack) with horizontal expansion (gaining access to Bitcoin-specific merchant flows).

Remember the story of Google’s Android buy? Instead of focusing on immediate revenue, Google prioritised two things that would simplify the entire mobile experience for hardware manufacturers and software creators. First, provide a unified system for manufacturers to adopt. This would eliminate the fragmentation plaguing the mobile ecosystem. Second, offer a consistent programming model so developers could create apps that worked identically across all Android devices.

You are seeing something similar play out as a general pattern in crypto. More than plugging immediate gaps, cash-rich incumbents are aiming to strengthen their market positions. When you drill down into the latest acquisitions, you see the gradual strategic shift in what is getting acquired and who is acquiring it. The bottom line is we are seeing signs of maturity across the board. Exchanges are fortifying moats, payments companies are racing to own rails, miners are bulking up ahead of the halving, and hype‑driven verticals like gaming have quietly dropped off the M&A ledger. The industry is beginning to learn which integrations actually compound and which simply burn capital.

Gaming is a great example of this. Investors collectively spent billions of dollars on supporting gaming ventures through 2021-2022. But the pace has dramatically slowed since. As Arthur had mentioned on our podcast, unless there’s clear PMF, investors are done with the gaming sector.

This context makes it easier to understand why so many acquisitions, despite their strategic intent, miss the mark. It's not just about what’s acquired, but how well it’s integrated. And crypto, while different in many ways, isn’t immune.

Why Acquisitions Often Fail

In The M&A Failure Trap, Baruch Lev and Feng Gu studied 40,000 acquisitions worldwide and concluded that 70-75% of them fail. They attribute failures to factors like large targets, inflated target valuation, acquisitions unrelated to the core business, operationally weak targets, and misaligned executive incentives.

Crypto has certainly produced its own acquisition failures, and we can see that the factors mentioned above are applicable here. Take FTX’s 2020 acquisition of portfolio tracking app Blockfolio for $150 million. At the time, it was billed as a strategic move to convert Blockfolio’s 6 million retail users into FTX traders. While the app was rebranded to FTX App and briefly gained traction, it failed to significantly move the needle on retail volume.

Worse, when FTX collapsed in late 2022, the association with Blockfolio vanished almost entirely. It wiped out years of brand equity. It’s a stark reminder that even acquisitions with strong user narratives can be undone by broader platform failure.

Many companies make the mistake of acquiring way too quickly. Here’s an image that shows how, perhaps needlessly, fast FTX was. It made acquisitions to get licenses, and this is what their corporate structure looked like after the acquisitions.

Polygon stands as a notable example of the risks tied to aggressive acquisition strategies. Between 2021 and 2022, it spent nearly $1 billion acquiring ZK-related projects like Hermez and Mir Protocol. Moves that were praised at the time as visionary. But two years on, those bets have yet to translate into meaningful user adoption or market dominance. One of its key ZK initiatives, Miden, eventually spun out as a separate company in 2024. Once at the centre of crypto conversation, Polygon has largely faded from strategic relevance. Of course, these things often take time, but as of now, there’s no material evidence of ROI on the amount spent on acquisitions. Polygon’s spree serves as a reminder that even well-resourced, talent-driven acquisitions can fall flat without timing, integration, and clear downstream use.

On-chain DeFi-native acquisitions have had their misfires, too. The 2021 merger of Fei Protocol and Rari Capital involved a token swap and joint governance under the newly formed Tribe DAO. On paper, it promised deeper liquidity, lending integrations, and DAO-to-DAO collaboration. But the merged entity quickly ran into governance disputes, a costly Fuse market exploit, and an eventual unwind that saw the DAO vote to return funds to token holders. What began as an optimistic experiment in protocol consolidation became a cautionary tale about coordination risk, execution failure, and the limitations of token alignment alone.

That said, crypto is better positioned than traditional industries for successful acquisitions for three key reasons:

Open-source foundations mean technical integration is often easier. When most of your code is already public, due diligence becomes more straightforward, and combining codebases is less problematic than merging proprietary systems.

Token economics can create alignment mechanisms that traditional equity can't match— but only when the tokens have genuine utility and value capture. When teams on both sides of an acquisition hold tokens in the combined entity, their incentives remain aligned long after the deal closes.

Community governance introduces accountability that's rare in traditional acquisitions. When major changes must be approved by token holders, it's harder for deals to be pushed based solely on executive hubris.

So, where do we go from here?

Build for the Bid

The funding environment today demands pragmatism. If you're a founder, the pitch should be both "Here's why we should raise," and "Here's why someone might buy this." Here are the three forces at play in today’s crypto M&A landscape.

First — Venture Funding will be more precise

The funding landscape has changed. Venture funding has plummeted over 70% from its 2021 peak. Monad’s $225 million Series A and Babylon’s $70 million seed round are outliers, not indicators of a rebound. Most VCs are focused on companies with traction and clear economics. With interest rates elevating the cost of capital and most tokens failing to demonstrate sustainable value accrual mechanisms, investors have become intensely selective. For founders, this means acquisition offers must be considered alongside increasingly difficult fundraising paths.

Second — Strategic Leverage

Cash-rich incumbents are buying time, distribution, and defensibility. As regulatory clarity improves, licensed entities become obvious targets. But the appetite doesn’t stop there. Firms like Coinbase, Robinhood, Kraken, and Stripe are acquiring to unlock faster go-to-market in new regions, gain embedded user bases, or compress years of infrastructure work into a single deal. If you’ve built something that lowers legal risk, speeds up compliance, or gives acquirers a cleaner path to revenue or reputation, you’re already in the consideration set.

Third — Distribution and Interface

The missing piece of infrastructure is the layer that gets products into users’ hands quickly and reliably. It is about acquiring the pieces that unlock distribution, simplify complexity, and shorten time-to-product-market fit. Stripe folded in OpenNode to streamline crypto payments. Jupiter acquired DRiP Haus to add NFT delivery to its liquidity stack. And FalconX absorbed Arbelos to add institutional-grade structured products, which probably made it easier to serve a different client profile. These are infrastructure plays designed to widen reach and reduce operational drag. If you’re building something that lets others go faster, reach further, or serve better, you’re on someone’s shortlist.

It’s the era of strategic exits. Build like your future depends on someone else wanting to own what you’ve made. Because it probably does.

Signing off,

Saurabh Deshpande

Disclaimer: DCo and/or its team members may have exposure to assets discussed in the article. No part of the article is either financial or legal advice.

The fed fund rate at 4.5% is a proxy for this. Until 2022, this was 0.25%. This means that the opportunity cost of capital to be deployed to fund early-stage ventures in crypto has increased by 18 times in the last three years.

Over 2022‑24 the CFTC issued, clarified or enforced a series of rules and staff letters that turned a hazy derivatives landscape into a roadmap incumbents could follow. For Coinbase, those tweaks removed three of the biggest unknowns: licence scope, clearing model, and custody obligations.

MiCA creates a “one-licence, 27-country” passport in Europe. This is huge for scale-seekers.

Basel guidance clarifies how banks can hold stablecoins, pushing acquirers toward fully-backed issuers.

What I find interesting is that Anthony Pompliano “The Pomp” has launched his first SPAC to make an acquisition in the crypto space. He raised about $258 million for that vehicle.

I would expect more of these deals to come to light as it makes total sense.

Great insights!