How to Market Make $500 Million a Week

Understanding RFQs with Katia from Bebop

Hello!

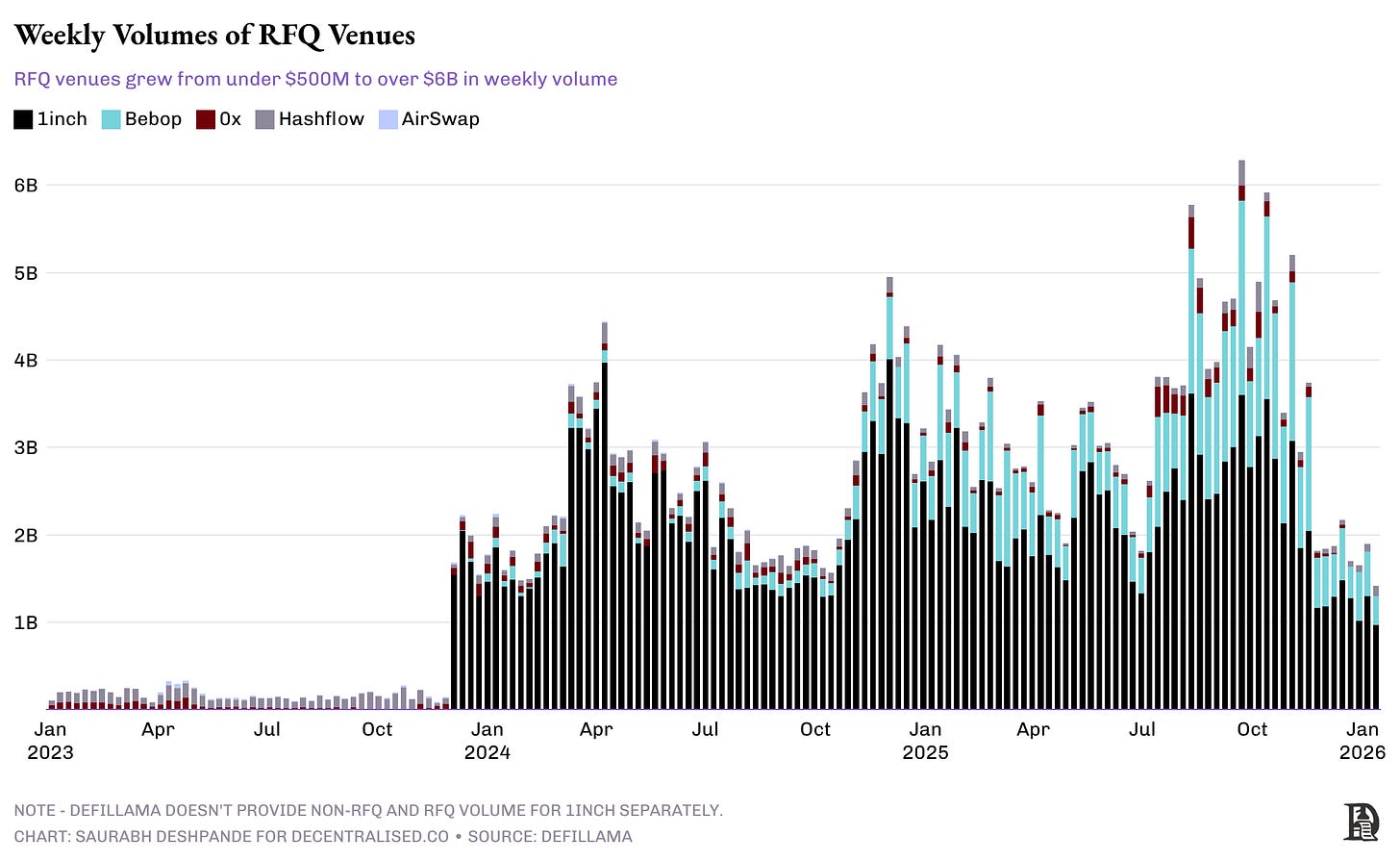

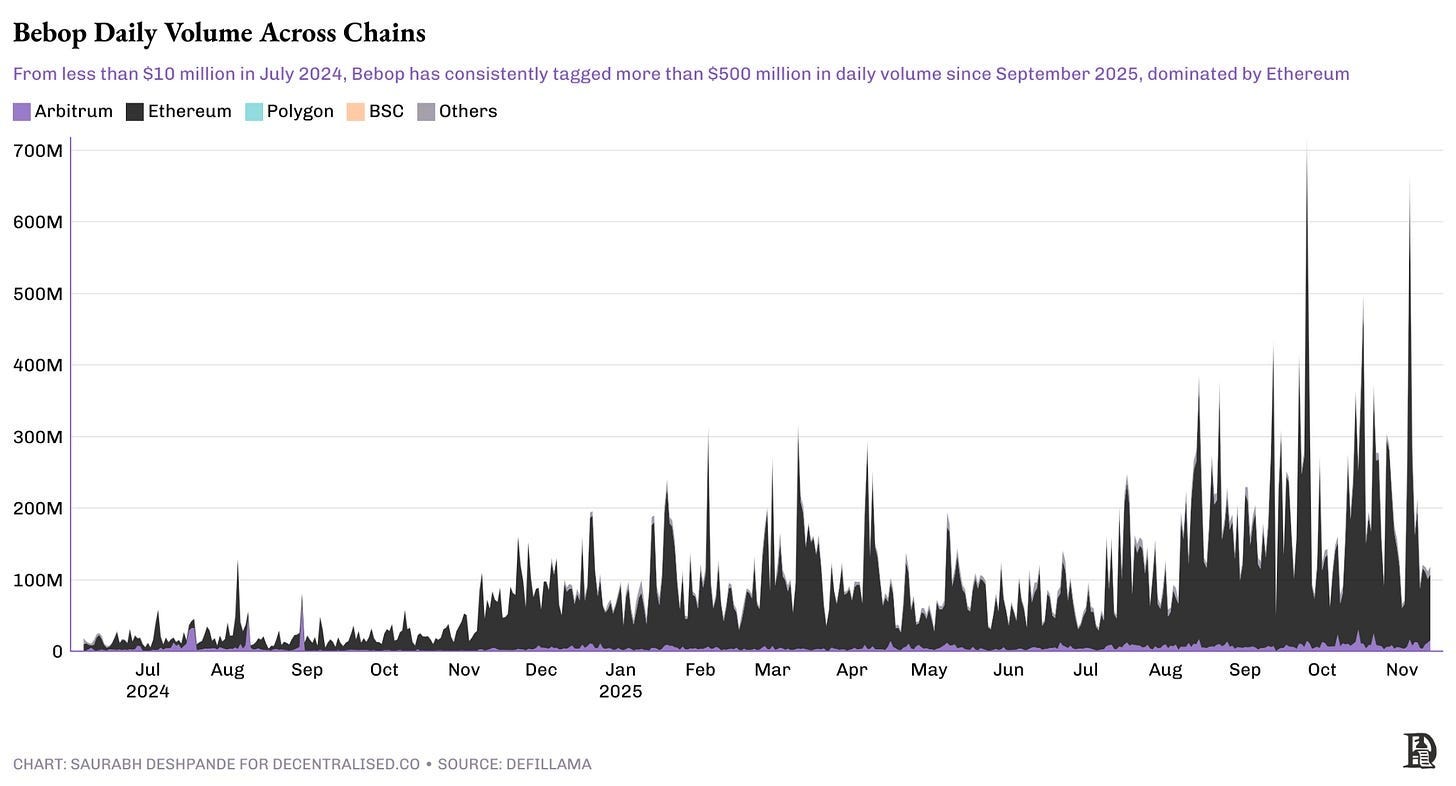

RFQ, aka Request for Quote, offers a simple premise. What if you could simply ask for a price before you bought? What if that price was guaranteed, signed, and settled without anyone else getting a peek? Bebop has been dominating the category for the past two years. These primitives are key to scaling new markets and have been used in TradFi for decades. Bebop has been recreating it on-chain to aid developers looking to empower users to access liquidity across asset types. They do $500 million a week in volume, according to DefiLama.

Today’s article, written in collaboration with Katia Banina, looks at how an ancient practice is being rebuilt on-chain, and why Bebop thinks it has found a way to filter out the lemons.

If you are exploring new markets, providing liquidity, or are a market-maker firm, consider reaching out to us at venture@decentralised.co. We are scouting for partners to provide liquidity to several of our portfolio companies.

Information about the product you purchase is critical to establish its price. The more you know before making a purchase, the easier the price discovery process is. Often, you verify the quality of a product only after you have purchased it. If you can verify it cheaply and have some recourse in the form of return or refund, it is all good. During the summer, I purchase mangoes directly from the farm and pay a premium over the market price. The premium is worth it due to the superior quality of these mangoes.

The farmer knows they are high-quality mangoes; I can verify it against regular mangoes. And agree to pay the premium. The information asymmetry between the seller and buyer disappears when verification is inexpensive.

What happens when the ability to verify is no longer available?

In 1970, George Akerlof wrote a paper called The Market for ‘Lemons’, for which he would win the Nobel prize in economics in 2001. The paper refers to the idea that information asymmetry destroys markets. He uses an example of used cars. Only the sellers know whether their cars run smoothly. The buyers do not, until they’ve bought and used these cars. Buyers anticipate this information asymmetry, and they tend to pay average prices. Owners of good cars (peaches) cannot afford to sell at average prices, and they eventually exit the market. So, all that is left are the low-quality cars and the lemons.

When three market forces align i) the ability to profit from an event, ii) access to technology to exploit it, and iii) access to material information, sophisticated market participants will move to maximise their profits at the expense of average participants. Call it the “three-body problem” of markets: when these three forces interact, they create conditions where extraction becomes inevitable.

You do not want that. Regulators and watchdogs are supposed to monitor markets to prevent these three forces from aligning in ways that harm regular participants.

We aimed to address these issues arising from information asymmetry by utilising the Web3 infrastructure. Blockchains are public. Smart contracts are auditable. Every transaction is visible. The code is law, and the law is transparent. But it introduced different issues.

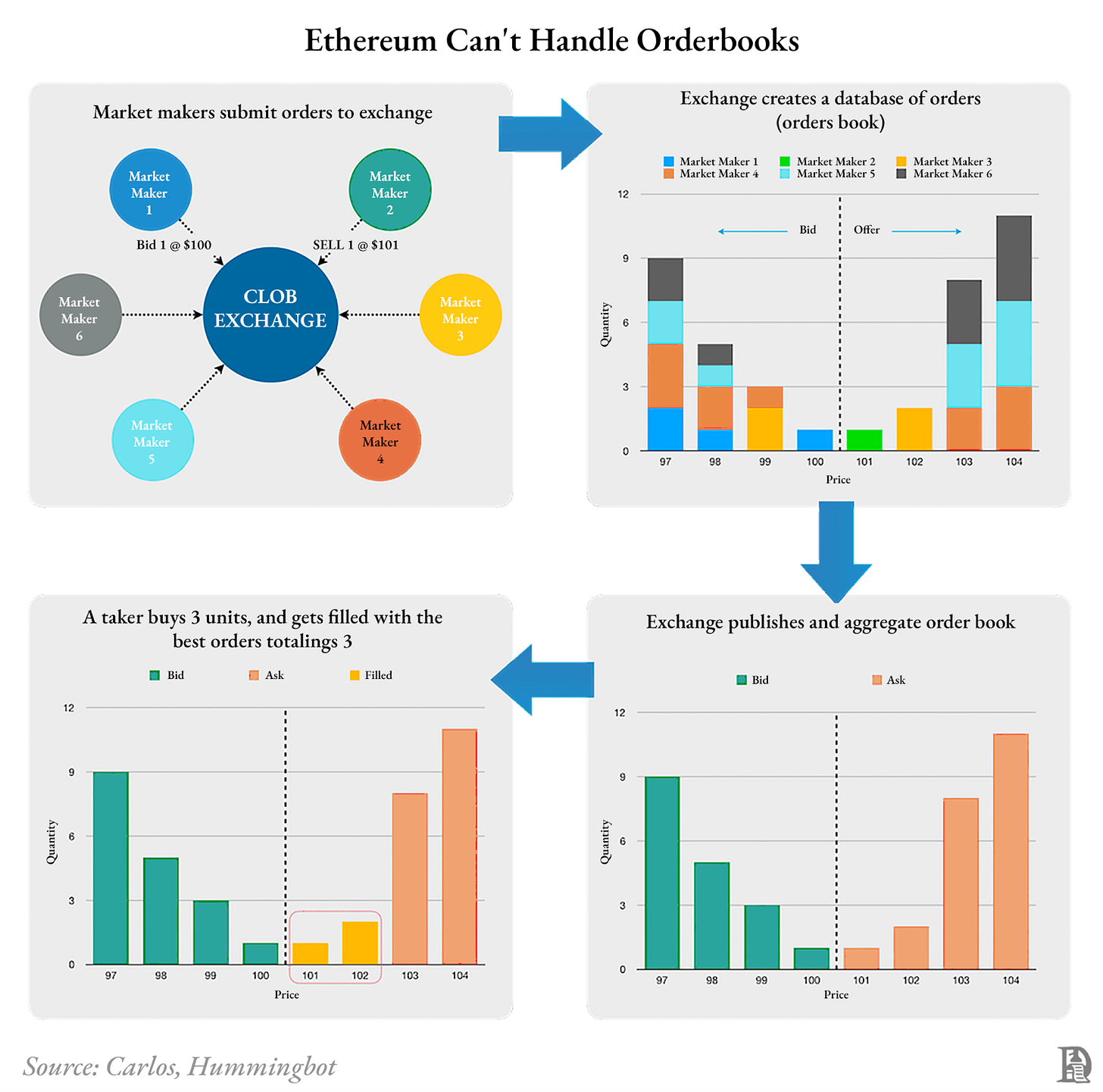

Traditional finance exchanges are based on order books. They are populated with buyers’ bids and sellers’ asks. When you market buy something, you fill the lowest ask first and then the second lowest, and so on. And the other way around when you market sell. However, given Ethereum’s slow blocks and gas limit constraints, placing and changing limit orders was difficult, making on-chain order book-based designs infeasible. AMMs came to the rescue. It also meant that nobody had to keep placing limit orders. You had a passive pool of capital that people could trade against.

AMMs allowed market participants to buy and sell assets based on a formula that prevented prices from fluctuating excessively. Importantly, that could operate independently from any single party that is opinionated on the fair asset value, i.e., a market maker. This is what you want from a market. Buyers and sellers should be able to trade in reasonably high quantities without significantly affecting the price.

However, the issue arises because of the way transactions are ordered from the mempool. When you want to buy or sell an asset and broadcast the order, everyone can see it. If there’s a possibility of ordering transactions in a certain way to profit, someone will do it. And it is a zero-sum game, when someone profits, someone is losing, which is most likely a retail participant. There’s the issue of how sophisticated players can exploit participants who lack information or access to technology. Sumanth has written extensively about it in his discussion of the inevitability of MEV.

When no professional market makers would touch crypto, automated pools allowed anyone to provide liquidity and earn fees. They made DeFi possible. But as markets mature, different tools emerge for different needs.

RFQ, also known as a Request for Quote, is an ancient concept. Humans have done it since the earliest days of commerce. It is about asking around for the best price before making a large purchase commitment. It then became a practice in industrial procurement. When governments award construction contracts to companies or an automaker like Tesla or General Motors wants to procure 5,000 tonnes of steel, they send specific requests to the relevant parties to obtain the best offer.

RFQ found its way to finance in foreign exchange, fixed income, and wider financial markets that are traded over the counter (OTC). Instead of posting orders to the public orderbook, you ask for quotes from market makers, who provide guaranteed prices for short periods of time.

The crux here is that there is competition to fill an order, allowing the buyer to get a better price. Consistent better pricing gives buyers the confidence, and thus, demand remains robust. Competition leads to better price discovery.

Financial markets adopted RFQ for the same reasons. It offers better UX. For example, Robinhood uses quotes from market makers for asset prices instead of routing to exchanges. In cases when orders are large, customised, or in markets with thin public order books or markets like foreign exchange with no order books, you can get a significantly worse price that eats into your margins.

A company that needs to exchange $100 million would not want to move the market by trading it in public markets. They would request quotes from several banks. Banks would have their internal risk assessment frameworks to provide quotes that stand for a stipulated time.

RFQ brings several inherent advantages that matter increasingly as trading becomes more sophisticated:

Superior price discovery. Market makers have a holistic view of the entire market. They see prices across centralised exchanges, multiple DEXs, derivatives markets, and order flow patterns. A Uniswap pool knows only what’s happened within that specific pool. When you request a quote, the market maker synthesises information from every venue they monitor, giving you pricing that reflects the genuine market rather than the isolated state of one pool.

CEX-quality execution on-chain. The best market makers in crypto are the same firms providing liquidity on Binance, Coinbase, and OKX. RFQ allows them to bring that same quality of pricing and execution to on-chain trading. You get centralised exchange depth (or better, because capital can sit on the same chain and be utilised across venues) without the custody risk.

Dramatic capital efficiency. In an AMM, liquidity must sit idle in pools, waiting for trades. RFQ liquidity lives in the market maker’s inventory system, where it can be actively managed, hedged across venues, and deployed only when needed. This means market makers can offer much larger fills at competitive prices. Where a pool might require $10 million of TVL to fill a $100,000 trade without excessive slippage, an RFQ market maker can fill that same trade using exactly $100,000 because they hedge dynamically across multiple venues.

Guaranteed execution and fixed prices. When a market maker signs a quote, they commit cryptographically. You know exactly what price you will receive. There is no slippage between quote and execution, no price that moves against you while your transaction waits in the mempool. The certainty matters enormously for larger trades or during volatile periods.

Modern intent protocols and sophisticated solvers are also addressing many of the MEV challenges that plagued early AMMs. The infrastructure is getting better across the board. But RFQ offers something fundamentally different: professional market-making rather than formula-based pricing. It’s not that AMMs are broken, it’s that RFQ enables use cases that passive pools cannot serve effectively.

Where AMMs excel at providing baseline liquidity for routine swaps, RFQ shines for larger sizes, exotic pairs, volatile conditions, and any situation where execution certainty matters more than permissionless simplicity. The future likely involves both, with aggregation layers intelligently routing each trade to wherever it can be executed most efficiently.

Both AMMs and RFQs have different privacy characteristics, each with its own tradeoffs.

When you request a quote through RFQ, you reveal your trading intent to the market makers before committing to anything. They see that you want to sell 100 ETH. They know current prices across every venue they monitor, and they understand which direction the market is moving. You have less complete information. This creates an asymmetry.

However, this asymmetry can be managed through good system design. Protocols implement various mechanisms to limit what information flows to makers, when they see it, and how they can respond. The challenge is not inherent to RFQ as a concept—it’s a design problem with known solutions.

Interestingly, AMMs reveal nothing about your intent during the quoting phase because there is no quoting phase. You see the current pool state and decide whether to trade. Your intent only becomes visible when you submit your transaction. At that moment, though, it becomes completely public. Your pending transaction sits in the mempool, where anyone can see it, analyse it, and act on it before you execute.

This is where RFQ provides a crucial advantage. Once you accept a quote, the market maker has cryptographically committed to that price. Your transaction settles atomically with no opportunity for someone else to insert themselves in between. No frontrunning, no sandwiching, no MEV extraction from reordering. The maker sees your intent earlier in the process, but no one can act on it adversarially.

The question becomes: what happens between the moment you request a trade and the moment it executes? In AMM pools broadcasting to the public mempool, sophisticated actors can sandwich your transaction or frontrun it, extracting value from the gap between your expected and actual execution price.

In RFQ systems, the signed quote eliminates this attack surface. The price is fixed at the moment of signature. So, there’s no slippage to exploit or opportunity to insert transactions before or after yours. For small routine swaps, the difference may be negligible. For anything substantial, guaranteed execution at a committed price offers meaningful protection against the extraction strategies that are prevalent in public transaction pools.

We should also note that both models continue to evolve. Intent protocols are adding privacy-preserving mechanisms to AMM execution. RFQ platforms are implementing techniques to minimise what information flows to makers and when. The privacy landscape is not static, and good design can address vulnerabilities in both architectures.

History of on-chain RFQ

Airswap kept RFQ peer-to-peer early in DeFi. Traders found each other, agreed on prices off-chain, and settled on-chain through the Airswap contract. This was suitable for sporadic trades but not for high-frequency trading.

In a traditional RFQ, once a maker quotes you, they are stuck with that price. Airswap implemented LastLook, which flips it. You sign the order, then the maker gets “last look” before executing. This makes trades gasless for users. The maker pays gas and takes execution risk.

0x approached the market from the other side and created an open protocol that anyone could use. Their RFQ-T (RFQ for Traders) system, launched around 2019, allowed professional market makers to provide quotes through a standardised API.

The separation of the infrastructure layer from the application layer allowed market makers to plug into 0x’s system, and any front-end could request quotes from these makers. This worked well for professional trading firms and aggregators, such as Matcha (0x’s own interface), but it remained primarily an infrastructure - most retail users never directly interacted with 0x’s RFQ system.

Every trading venue has a chicken-and-egg problem of liquidity and users. Without liquidity, there will not be users, and without users, there is no liquidity. Hashflow, launched in 2021, addressed the liquidity problem by throwing money at it. But capital alone will not solve the problem if using the product comes with technical overheads. Hashflow developed a pool-based architecture to address the issue. Traditional market makers were figuring out blockchains; you could not just throw smart contracts at them and expect them to solve technical complexities in-house. They could park capital in pools, and Hashflow used it for RFQ.

0x demonstrated that RFQ could work on-chain, but it did not solve the go-to-market challenge. How do you make RFQ accessible and understandable to regular DeFi users who were accustomed to simply swapping on Uniswap?

Hashflow, launched in 2021, took an aggressive growth approach. They raised significant capital and used token incentives to onboard market makers. For a nascent market where order flow was uncertain, these incentives proved effective in bootstrapping liquidity. Hashflow positioned itself as a full-stack RFQ platform with its own interface, market maker network, and user base.

When the incentives were on, Hashflow volumes declined. In 2023, the overall 1inch volume increased around the USDC depeg.

One can think of RFQ as a quote produced from an order book that’s frozen in time. Market maker is essentially pausing time and finding the best quote from across venues. It usually yields better results than trading on a single venue. This can be verified with low slippage and high depth offered by Bebop on many pairs. But RFQ does have its issues with informed toxic flow.

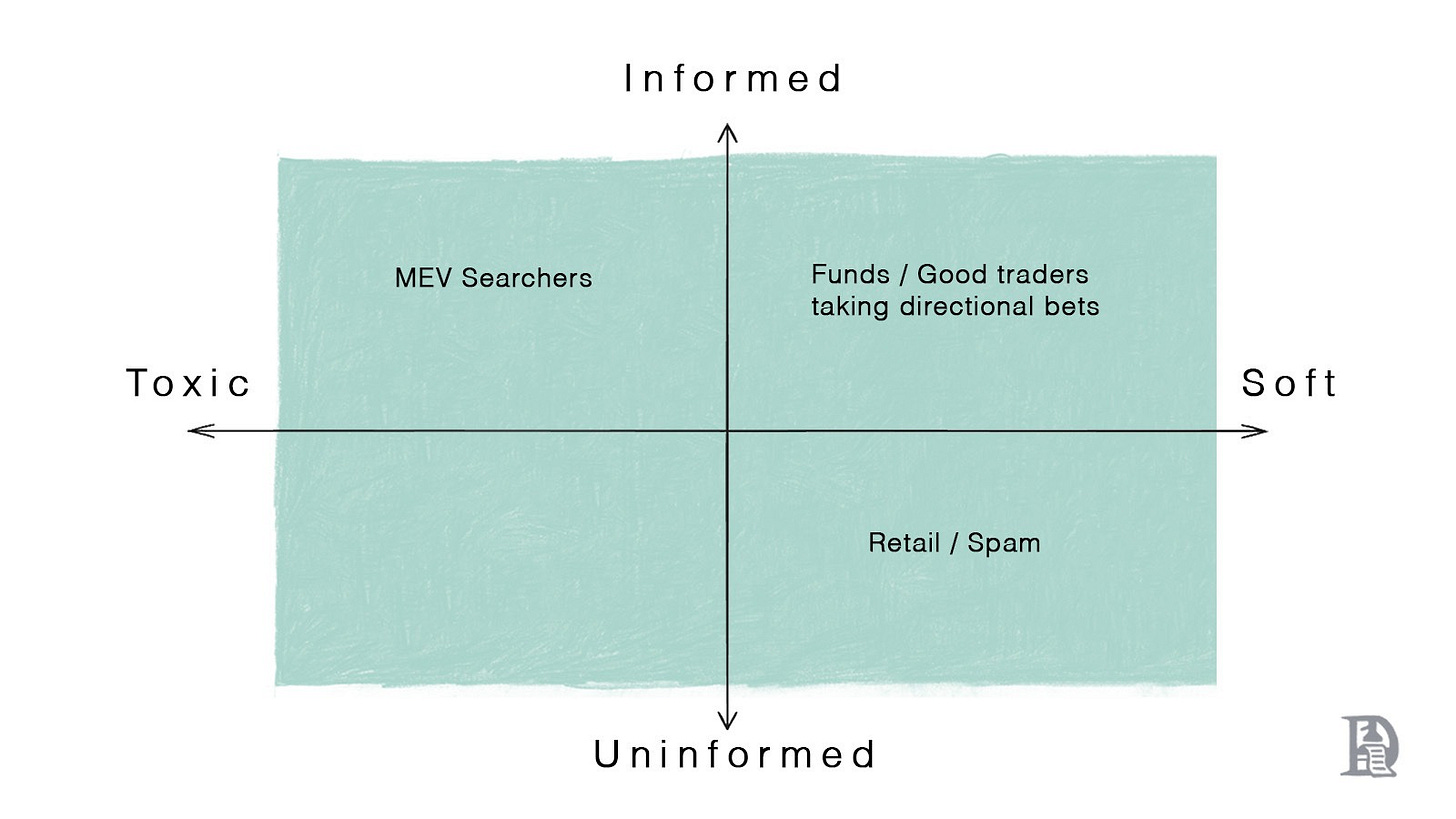

Imagine you are a liquidity provider in a DeFi RFQ system, offering guaranteed price quotes that live for 30 to 60 seconds. Every trade request that comes through could fall anywhere on a spectrum, ranging from toxic to soft on one axis and from uninformed to informed on the other.

In the bottom-right quadrant sits spam. These are high-frequency, uninformed trades that arrive without any real market knowledge. They are soft because they follow predictable patterns and do not adversely select against you.

Move up to the top-right quadrant and you find good traders. These are informed participants who understand markets deeply but are making genuine directional trades. A fund manager rebalancing positions, a treasury executing a planned allocation. Still profitable to serve. But now the trouble begins.

The extractors and MEV searchers lurk in the top-left quadrant. These are highly informed toxic traders who understand precisely what they are doing. They might request two quotes from you 15 seconds apart, then execute both in the same atomic transaction, profiting from any price movement while you absorb the loss. Or they will sit on your quote, simultaneously watching prices across other venues, only executing when they can arbitrage against you.

They might even slice a large order into ten smaller pieces to exploit your tighter spreads on small sizes, then bundle everything into one transaction. They get the price of ten small trades with the economics of one large trade.

You cannot tell these quadrants apart. Every request looks identical on-chain. Just as used car buyers could not distinguish lemons from peaches, you cannot distinguish MEV searchers from good traders or spam until you have been arbitraged. So you widen your spreads to protect yourself. You shorten quote validity windows. You become more cautious. But this defensive posture punishes everyone, including the good traders and even the spam flow that would have been profitable to serve. Other liquidity providers observe the same pattern and follow suit.

Eventually, the best makers exit entirely because they cannot sustainably serve a market where they cannot accurately price risk. The toxic flow has degraded the entire market structure, driving out the quality liquidity providers and leaving behind only those willing to extract value or charge prohibitive spreads. Remember how bad sellers drove buyers out of the market, as seen in the case of used cars? In this case, instead of bad sellers driving out good sellers, bad buyers drive out good sellers.

RFQs protect trades from leakage. Liquidity is created on demand. The taker asks privately, the maker quotes privately, both sides decide privately, and only the final execution is recorded.

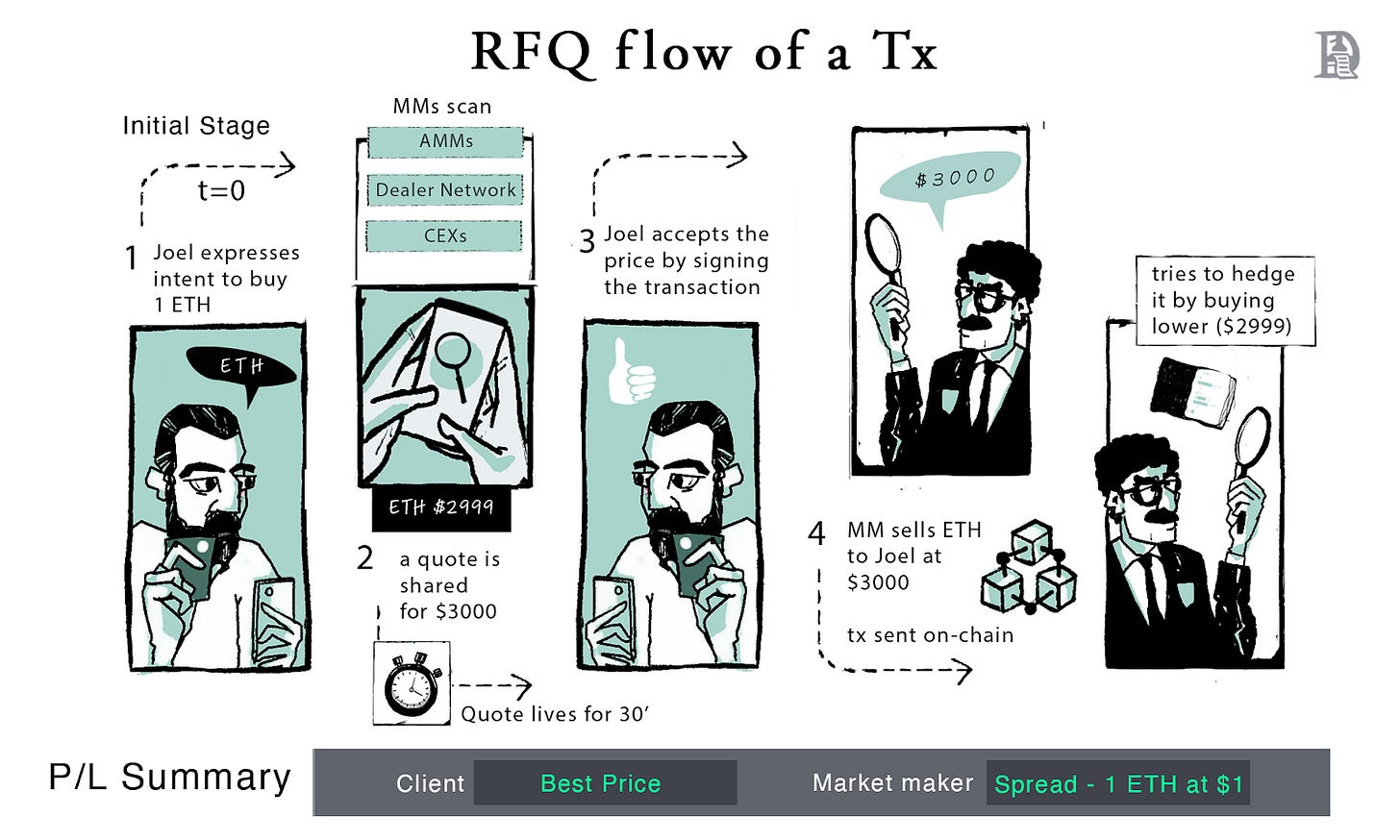

In the example below, Joel submits an RFQ for 1 ETH. The market maker scans venues, including AMMs, CEXs, and other dealers, to reduce price risk. He then quotes the price of $3000 to Joel. If Joel accepts, the market maker hedges his position by buying ETH at a lower price, say $2,999 (not guaranteed).

The anticipated spread is $1. The quote is live for 30 seconds. If Joel accepts, the transaction is sent on-chain and settled atomically. Note that the market maker can only hedge once Joel signs the intent.

When the order flow consists of legitimate buyers, these takers receive competitive execution. Makers earn a small but fair spread. Makers price tightly because they’re confident they won’t be picked off and can keep the quote live for longer.

How Bebop Differs

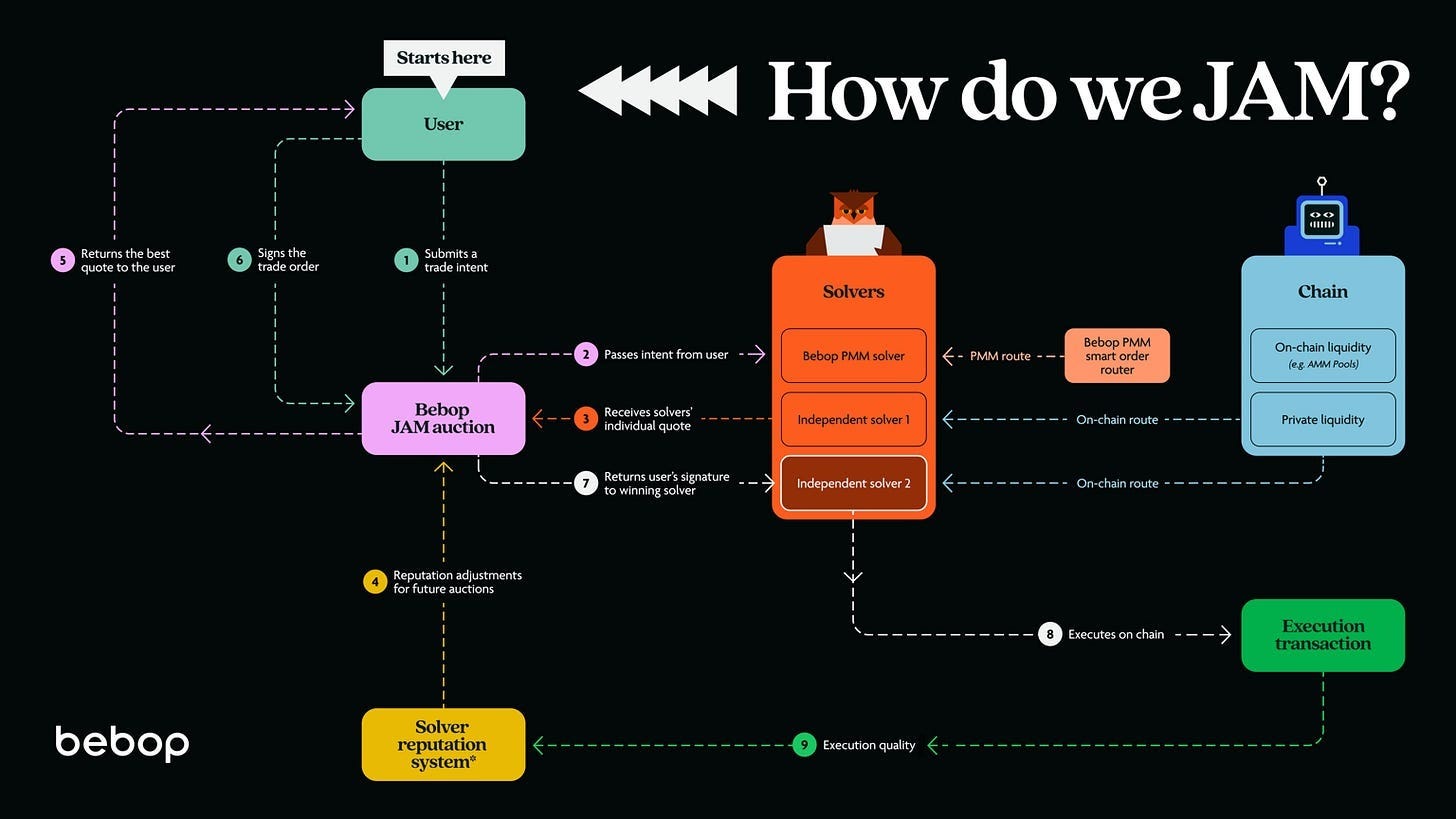

Bebop tackles toxic flow through several defensive layers. The first is the last look, borrowed from traditional finance. When a user requests a quote, they provide a signature committing to the trade. The market maker then provides their own signature to complete it. But crucially, the maker retains the option to reject the trade if the market has moved adversely between quote and execution.

This disproportionately affects arbitrageurs who only submit trades when prices have shifted in their favour, while having minimal impact on regular users executing near the quoted price.

This dual approach matters because different types of trades benefit from different liquidity sources. A large swap into a major token might get better pricing from market makers who can internalise the order and manage their inventory efficiently. By maintaining both channels, Bebop captures the advantages of each.

So, where will you trade in the future?

The trajectory seems clear. Pure AMMs, as they are, face an existential version of the lemons problem. As markets mature with more sophisticated participants, the toxic flow will continue to drive good liquidity away from passive pools. We have already seen this play out. The most significant trades, the most professional users, and institutions tiptoeing into DeFi are not using raw AMM pools. They are routing through aggregators that tap into RFQ liquidity alongside automated market makers.

This is where Ben Thompson’s aggregation theory begins to show itself. It says that when the supply is cheap to spin up, value flows to the entity that gathers this supply and maintains a relationship with the user. RFQ venues aggregate AMMs, market makers, centralised exchanges, and DEXs with order books. They see the most traffic, understand which makers are best suited for each type of order, and they serve as the default entry point for users. Once that loop tightens, it becomes difficult for a standalone pool to compete for serious size on its own.

Sure, for simple swaps, AMMs are fine. However, for anything significant, exotic, or during volatile periods when prices fluctuate significantly before blocks are finalised, we’ll want an RFQ. The future looks like aggregation layers that understand this distinction, routing each trade to the location where it can be executed most efficiently. Obviously, Uniswap will still exist, but it will increasingly serve as one liquidity source among many, with RFQ market makers filling the gaps that formula-based pricing cannot handle.

I see no reason why an RFQ should stop at spot markets. Consider options for a moment. Sophisticated derivative instruments are used tremendously in traditional finance. Barely has PMF in DeFi. Options pricing requires sophisticated models that account for volatility surfaces, time decay, Greeks, correlation structures across strikes and expiries. You cannot encode this into a simple bonding curve. Market makers who understand these dynamics can quote options via RFQ, bringing genuine two-sided markets to on-chain derivatives.

The same logic applies to structured products, anything combining multiple instruments into a single payoff. These products are too complex for AMMs, but they are perfect for RFQs, where a market maker can price the entire structure and offer a single quote.

Tokenised assets or RWAs are a consensus bet in DeFi. They will become practical only with an RFQ. Traditional finance hates locking up liquidity. Every dollar that is locked could be earning yield or doing something productive. So, it is doubtful that only AMMs will house RWA liquidity. RFQ lets you bring the pricing models from traditional markets on-chain, with market makers who understand both worlds providing the bridge.

What is emerging is a more mature market structure. DeFi’s early phase needed AMMs because it was in a stage where nobody believed in us. There were no institutions, no market makers, no professional LPs. But now, they are here. As markets mature, the infrastructure needs to get more sophisticated. RFQ does not replace AMMs so much as it completes the picture, filling in everything that passive formulas cannot.

We are creating a financial system that combines the transparency and composability of DeFi with the efficiency and sophistication of traditional markets. You could trade anything, of any size, with confidence in execution. Market makers compete on price rather than on who can extract the most MEV. Users receive genuine best execution, rather than hoping their transaction does not get sandwiched. And new markets become possible that serve needs we have not even articulated yet.

This is how DeFi evolves without sacrificing what made it interesting in the first place. The infrastructure becomes more sophisticated, but the fundamental openness remains. Anyone can still participate. The protocols stay neutral. The difference is that now there are real professionals providing liquidity, not just passive pools hoping they do not get picked off. The lemons get filtered out, and what remains is a market where quality can survive.

Learning how payments scaled on the internet,

Saurabh Deshpande

Hot takes:

- RFQ systems institutionalize asymmetry rather than eliminate it.

- AMMs are reactive systems that must be arbitraged into correctness. They price history, not intent. Arbitrage is the fee paid to synchronize stale state.

Akerlof’s “lemons” problem appears wherever markets depend on hidden information. CEXs are the clearest case. They see order flow, inventory, and liquidation risk before users ever do.

RFQs mitigate some of that damage by pulling intent off public rails and fixing prices up front, but they preserve the same underlying assumption: that someone must be trusted to price, route, and execute trades with privileged knowledge. The quoter still knows more. 🤔

The more interesting question is what markets look like when that assumption breaks. When no party needs advance knowledge because execution itself is verifiable.

Here at RealityNet we're exploring a different resolution: treating every swap as a global OTC agreement enforced by verifiable computation, without AMMs, wrappers, or privileged intermediaries. True atomic p2p swaps across chains, forming a shared global order space that cannot be gamed. In that world, price discovery becomes public knowledge.

If execution and settlement are provable at the protocol layer, how much of the lemons problem disappears by design?

Welcome to Reality