Does Crypto Matter?

How crypto will (and will not) change the world

Today’s article provides a framework for founders to think about the role of blockchains and the types of problems it is best positioned to solve and capture value from. If you’re an early-stage founder building something that uniquely benefits from crypto, we’d love to talk to you.

Also, earlier today, we took a podcast episode with Arthur from Defiance Capital live on our YouTube channel. Watch it after reading the article for insights on the state of liquid markets and drop in your valuable feedback. It is a new medium we are expanding to.

Hello!

The world has been stunned by visuals of Mechazilla capturing booster rockets after a successful mission to space last week. It comes in an age where AI has taken over the public psyche. NVIDIA’s stock performance over the past few months is reminiscent of firms adding blockchain to their name in the mania of 2021. Except, this time, there’s substance to the hype. AI as a sector has been capturing meaningful amounts of attention, capital, and talent.

In contrast, blockchains (or crypto) as a sector feels lost in a world of jargon soup sprinkled with meme assets atop it. It is hard not to feel like one is wasting time continuing to build in the sector. There is definitely the occasional bull-market rally, and price (or markets) are a huge contributor to what keeps people working within the industry. We are either at the cutting edge of what the internet can evolve to be or in the middle of a massive psychological experiment studying what happens when individuals can make markets out of anything.

Perhaps both.

Today’s piece, written in collaboration with Michael from Monad, explores a simple question. Why do blockchains matter? As a system of innovation, are they as relevant as space exploration or AI? Are we wasting our time? To find answers, we draw parallels with history. In particular, with that of the automobile industry.

Ford vs Toyota

Before Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903, automobiles were a luxury accessible only to the wealthy. Cars were built individually, often by hand, resulting in low production rates and limited availability of skilled labour. Ford's genius lay in shifting manufacturing to a moving assembly line, where each worker performed a specific task as the car moved past. By breaking down jobs into simple, repeatable actions, Ford could employ less skilled workers for many tasks. This dramatically increased production rates, reduced costs, and made cars affordable to the Middle Class.

Mass vehicle ownership transformed society in multiple ways. Horse carriages, once the primary mode of transportation, quickly became obsolete. People could travel further for work and leisure. Countless new jobs emerged, not only in the automotive sector but also in supporting industries like rubber, steel, and oil. Roads reshaped physical landscapes, while modified Ford vehicles served as tractors and boosted agricultural productivity.

Ford's rise marked a clear "before and after" moment in human history.

In the aftermath of World War II some 50 years later, Japanese car manufacturer Toyota teetered on the brink of bankruptcy. The government had refused a bailout, 1,600 workers were laid off, and founder Sakichi Toyoda had resigned. Only a U.S. military order for vehicles to use in the Korean War kept the company afloat. Around this time, Eiji Toyoda (the founder’s cousin) and Taiichi Ohno began reimagining automobile assembly line operations. Inspired by American supermarkets, they introduced systems like Just-In-Time, Lean Manufacturing, and Kanban.

These changes made Toyota’s manufacturing more efficient, productive, and affordable while improving the quality of its cars. The once near-insolvent company grew into one of the world’s largest car manufacturers and built a reputation for reliability.

Over time, the "Toyota Way" became standard in the automotive industry and operations across all sectors—from healthcare and retail to chip manufacturing and software development. While Toyota's rise may not have been as sudden or dramatic as Ford's, it changed the world in a subtle, gradual, yet profound way.

Innovation comes in many flavours.

The Schumpeterian perspective, derived from economist Joseph Schumpeter's works, views innovation as the primary engine of economic growth. Schumpeter introduced the concept of "creative destruction," describing the process by which new technologies and innovations disrupt and supplant outdated ones, thus propelling economic progress.

In simpler words, these are the before-after breakthroughs that exponentially boost human productivity and unlock vast reserves of latent economic value. This includes the likes of Henry Ford’s assembly line, the printing press, microprocessors, the internet, and AI.

In contrast, the Coasian view, rooted in economist Ronald Coase's ideas, focuses on transaction costs and the role of institutions in mitigating these expenses to facilitate economic activity. Coase argued that economic systems and institutions exist primarily to minimise the costs of transactions and coordination between individuals and organisations.

The Coasian perspective draws attention to less obvious but equally critical infrastructure that supports economic efficiency. Improving these institutional frameworks can lead to significant economic gains, though these benefits may not be immediately apparent. DAOs are probably a good instance of a Coasian innovation.

Toyota's manufacturing innovations initially transformed the company's fortunes, then changed the economics of the automotive industry, and eventually influenced all sectors. However, this transformation occurred gradually, with its impact becoming evident only in retrospect, rather than during the transition itself.

Other advances like double-entry bookkeeping, stock exchanges, open-source software, and making rocket boosters reusable are instances of technology progressing in the Coasian sense. While perhaps less dramatic than their Schumpeterian counterparts, these innovations have increased economic efficiency and propelled humanity forward in an equally important way.

What about Crypto?

Consider the sectors where crypto has already found product-market fit or stands on the brink of doing so.

First, you have Bitcoin, which has grown into a trillion-dollar asset and established itself as a legitimate, institutionalised store of value. It shares most of gold’s properties—scarcity, durability, portability, divisibility, and inertness. Time will determine if it surpasses gold as the de facto store of value. If it does, it will be due to its more efficient implementation of these properties. It has its own ETF. At least Wall Street thinks it is an asset worth paying attention to.

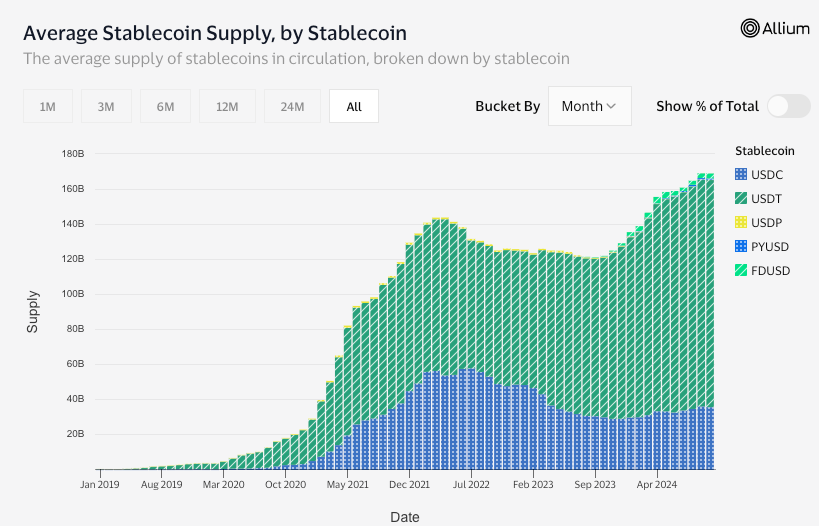

Next, stablecoins, which provide a cheaper and faster way to make cross-border payments compared to traditional routes. There is meaningful market demand for it. The fact that the total supply of stablecoins has gone from $500 million to $168 billion is proof of it.

It is worth thinking about why this is the case. A fiat transfer from one nation to another involves a bunch of intermediaries such as banks, governments, and providers like Western Union. Each of these exists to provide a layer of trust as a service and add a fee (either in the form of money or time) for doing so. Blockchains, as highly secure, transparent, and decentralised ledgers, exponentially reduce the cost of trust. Stablecoins are cheaper and faster because the Ethereum blockchain can be trusted as much (in fact, more than) the combination of institutions that fiat currencies rely on.

The same holds true for sectors like decentralised finance (DeFi) and digital art (NFTs). In DeFi, interacting with smart contracts is more efficient than dealing with intermediaries such as banks, brokerage houses, and exchanges. Before NFTs, auction houses served as trust intermediaries between collectors and artists. An unknown artist couldn't sell a piece of art for $100,000 without approval from an auction house. Once again, Ethereum provides comparable (if not better) trust guarantees that are quicker and cheaper.

More recently, we’ve seen the emergence of various kinds of DePIN networks. Are these networks creating fundamentally new services? Not really. Mobile data, electricity, GPUs, satellite data, and digital maps exist independently of blockchains. However, their monetisation and distribution economics are either inefficient or rely on centralised institutions. DePIN networks are trying to implement better forms of coordination.

Crypto is, at its fundamental core, a Coasian technology. Sure, when you analyse crypto from a financial perspective, it does mark many before-after moments. But when you zoom out, you will realise that finance enables human coordination and productivity. Finance itself is Coasian.

Crypto will not change the world in the way AI or rockets will. It is not meant to do that. Instead, crypto has a different role to play. It will help gather data to train our LLMs and provide AI agents with the means to transfer value among themselves. It will accelerate the pace at which new networks are formed. It might just help the next Elon Musk move out of a third-world country to the US. But on its own, crypto may not disrupt the fabric of society as we expect it to. It is the paint, not the canvas itself. What’s drawn with it remains to be seen.

As technology progresses on its exponential trajectory, crypto will grease the wheels, pave the roads, and strengthen the bridges.

Crypto will change the world in its own way.

Enjoying the Ethereum vs Solana debate on CT,

If you’re an analyst looking to turn an interesting idea or insight into a story on this publication, reach out to us here.

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

- On OEV