Beyond Consortiums

When interoperability comes to private chains.

Hey there,

TL:DR: Today, we break down one of J.P. Morgan’s research publications on interoperability between enterprise blockchains. I explain why it matters, then zoom out and ponder why enterprise solutions have historically struggled to disrupt anything.

Around 2017, during my initial years as an analyst, I kept a tracker for enterprise adoption of blockchains. The naïveté of youth and the exuberance around distributed ledgers made me believe that large corporations would soon embrace blockchains. Safe to say, that did not happen to the extent of my prediction.

With every market cycle, teams at enterprises with interesting titles like 'Innovation Management' or 'Future Initiatives' develop blockchain use cases. When the cycle wanes, they shift to other things, like AI or chatbots. I gradually realised that large organisations' incentive models generally do not allow management to embrace emerging technologies.

If the past few years prove anything, enterprise blockchain solutions struggle to scale. The timeline below is a handy list of enterprise initiatives that have emerged as Proof of Concept (PoCs) over the years. And yet, if you ask around how many people have used these, you may not know anybody. The land of enterprise blockchains, is filled with initiatives that eventually wind down.

For instance, IBM's food-tracking solution launched in partnership with Walmart only tracks leafy greens and bell peppers. Maersk's supply chain product was shut after several pilots. Even spending $150 million+ on blockchain initiatives doesn't help sometimes. In 2016, ASX (Australia Stock Exchange) began an initiative to clear trades and issue dividends using a blockchain.

Theoretically, it made sense. In reality, senior executives failed to bring the product to market after repeated attempts and eventually scrapped the project altogether after apologising in 2022.

A recent paper by JP Morgan's Onyx initiative caught my attention. Partly, instead of observing standalone use cases such as supply-chain management or debt issuance, it prioritises connecting different kinds of blockchains. So an enterprise (say McDonald's) might have BurgerChain, and a different one (like KFC) could have FriedChickenChain – and the two would have mechanisms to interact with one another.

This interested me because it addresses a core problem with all enterprise blockchain initiatives. Instead of replacing silos (databases) with new silos (private, permissioned chains), JP Morgan is trying to connect silos. Think of it as blockchain bridges for enterprises.

Today's newsletter examines how the company is building these bridges and what it could mean for the industry going forward.

The PoC

The paper starts with a simple problem. Trillions of dollars in value are held in what is considered 'alt' investments. An alt investment portfolio could include a mix of collectables, real estate holdings, and private equity allocations. Unlike listed equities, alts struggle from a lack of liquidity and regulations, often leading to the mispricing of assets that go towards them.

A person might want to sell highly desired artwork at a distress price. Or there might be a person on a different continent willing to pay more for debt given to artists of a certain genre.

These alt assets often struggle with a lack of liquidity. The PoC made by JP Morgan had two aims:

To facilitate global reconciliation and settlement of ledgers for illiquid investments

To improve liquidity for said investments globally and across financial institutions

When you build a portfolio on-chain with crypto, your best bet for distribution is an extensive integration or token rewards. Yearn was an excellent outlet during DeFi summer. An alternative is an exchange partnering up with you. However, exchanges have no reason to distribute financial products to users as its business model is (generally) predicated on users' completion of multiple trades daily.

JP Morgan’s PoC assumes individual portfolio managers (PMs) would distribute it to clients. These PMs would suggest assets (to clients), balance portfolios, and source liquidity for their portfolios using the product. JP Morgan calls the front end of the product Crescendo. It is a simple interface that allows PMs to allocate money attached to assets that may be held on separate chains across different financial organisations.

All of this feels like standard stuff. I can buy a mix of mutual funds from my bank account today. But what happens in the back end is what holds promise. Much like what occurs with traditional wealth management products, PMs suggest a mix of assets for a portfolio. These portfolios are issued as smart contracts on Onyx Digital Assets.

Tokenised instruments representing fixed-income products, private equity or private credit are issued on Provenance Blockchain, Onyx (by JP Morgan) or an Avalanche chain by service providers like Oasis Pro. A token standard compliant with ERC-20 named the Onyx Digital Assets Fungible Asset Contract (ODA-FACT) is used on all of them. Axelar and LayerZero are used for sending messages for buy or sell orders, whilst Biconomy is used to abstract the complexities of managing private keys or holding gas for transfers.

The result is a simple interface that allows investors to see what their PMs are investing in. PMs in exchange, have a trail of each of their orders going through the platform. The tokenised instruments – be they debt, equity or more esoteric instruments, like art – are still managed by large wealth management services like JP Morgan. But now, you have a mechanism allowing these instruments to interoperate with services from different banking entities with a fraction of the friction.

In these instances, the wealth management services still own and manage the underlying instruments. That is, you are not buying debt from a fintech company in an emerging market or real estate from a developer; the issuers for all of those assets are still large banks like WisdomTree, JP Morgan or Apollo. This process drastically reduces the typical risk for a person holding an investment portfolio with the platform as (I presume) the bank would have done necessary due diligence before listing an asset as an investment opportunity.

But why does any of this even matter? I believe it illustrates a moment when the lines between DeFi and fintech are increasingly blurred. Let me explain – first, with a breakdown of why enterprise blockchain initiatives have historically failed and then with an explanation of why DeFi products fail to scale.

Why It Matters

Enterprises usually struggle to find PMF for their blockchain initiatives. It comes down to the economics of operating blockchain-native business models. There aren't enough people rushing to track their milk supply on-chain.

Surely, certain luxury items can be traced on-chain if a user wants to; however, the market for that is currently tiny because consumer perception of blockchains as a verifiable trail of a product's provenance is not established yet.

Bringing off-chain goods - be it fruits, Gucci bags or real-estate to the blockchain requires long, manual processes that don’t happen easily. The tracking has to be integrated into processes in a way that is tamper-proof. Digital goods on the other hand, are relatively easier to show provenance for.

A different reason why enterprise blockchain initiatives struggle is that they interface with multiple parties in the real world, each of whom has very different incentive mechanisms. In some instances, systems would stick to relative obscurity even when it slows down the process because that benefits the stakeholders involved.

For instance, replacing the invoicing systems used at a dock could (rightfully) cause friction for a corrupt officer working there. Or a farmer may have little reason to spend his time slapping blockchain-native QR codes onto his produce if it does not mean he can charge more. The incentives break down when you take a nascent technology to multiple stakeholders.

What the PoC from Onyx has done stood out for a few reasons.

Firstly, they stuck to a handful of assets the banks already distributed among the wealthy clientele who interfaced with them.

Secondly, they created interoperability among all of them for the assets. A PM could source liquidity from bank A (which uses Provenance Blockchain) to service a client who uses bank B (which uses a permissioned instance of Avalanche).

Lastly, they stuck with a pretested business model. The focus of the PoC was to bring speed (and possibly composability) into a relatively slower fragmented process.

Now, one could argue this sounds like interoperable databases. It seems like the engineers at these organisations have managed to make a server on AWS speak to a server on Azure. But it goes beyond that, in my view.

The token standard used is ERC-20 compliant. So hypothetically – and this is a big IF – there is a pathway for these banking instruments to interface with permissionless public blockchains. I don't expect them to be accepting deposits in ETH, especially if it came from trading a random meme asset. There are compliance risks with that.

We have written about how the lines are blurring between DeFi and CeFi in the context of loans. You can extrapolate it to more nascent consumer categories, too. For instance, Zamp and Dinara are examples of B2B banks that permit remitting money to employees in both fiat and stablecoins. Mastercard has a program that allows issuing debit cards to crypto-native users.

But here’s what may have gone unnoticed in that PoC

Enterprise blockchains could communicate with one another.

They could (theretically) onboard crypto-native sources of capital or issue assets that settle on-chain in a public, permissionless environment.

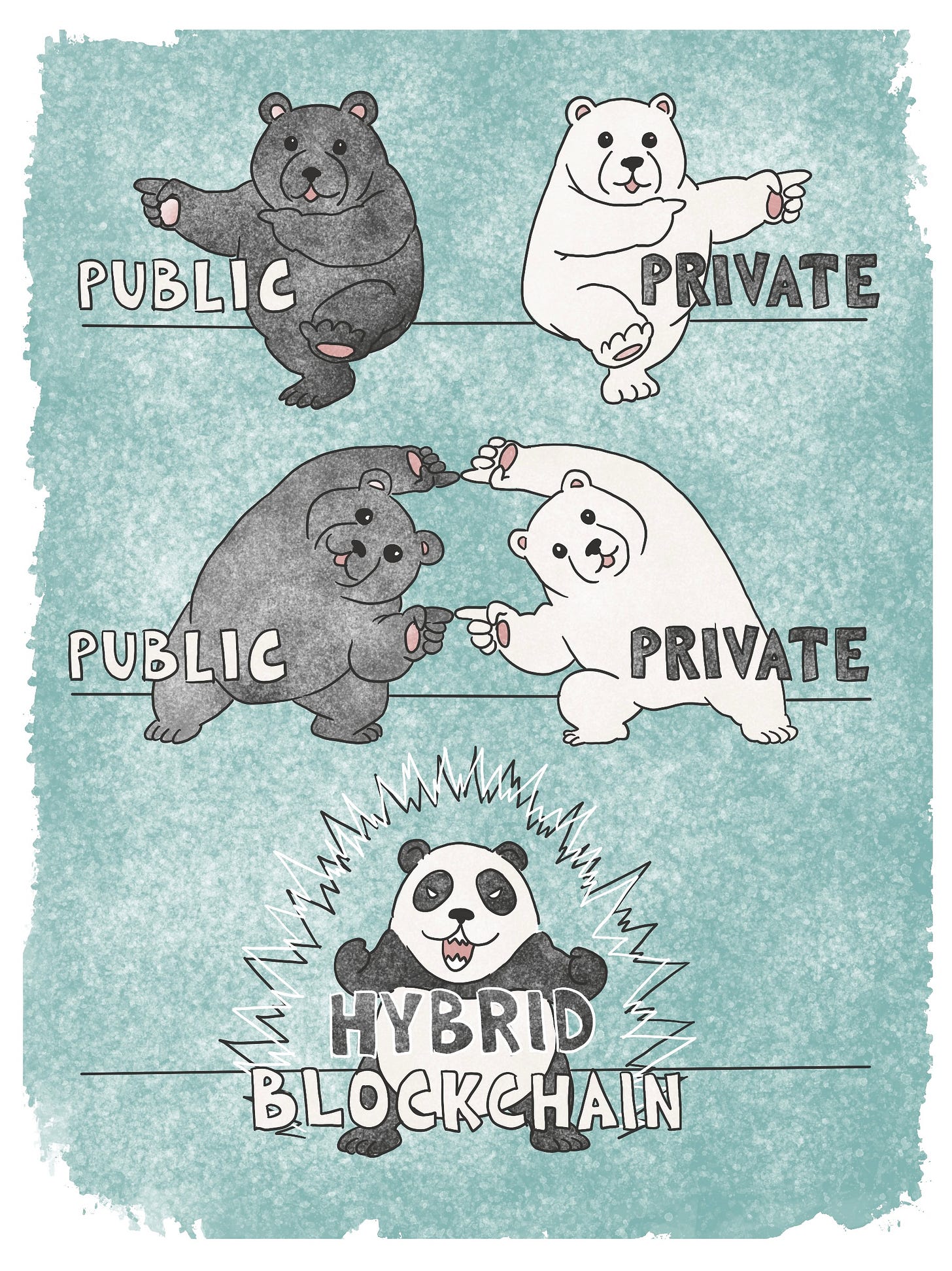

Blurring boundaries between private and public blockchains opens up new use cases that were not possible in the past. Before I explain, let's quickly revisit the current state of DeFi.

What It Means

You'll see a consistent, repeating issue when you consider projects in DeFi focused on real-world use cases (or RWAs, as the cool kids call them). The average person in crypto is not looking to make a 7% APY over the next year. Their incentive is to be risk-on and generate 30–50%.

The way it historically worked is that lending pools would offer native tokens in exchange for lending on them. Thus, for depositors on DeFi platforms, part of the yield did not come from the borrower; it came from selling tokens. But what happens when token rewards no longer exist? The appetite for lending declines rapidly.

Present-day DeFi products that source capital from crypto-native users struggle to scale because token incentives can only take them so far. According to DefiLlama, some $55 billion is locked in DeFi. Of this, less than $250 million is deployed into RWA projects. We are at less than 0.5% penetration with crypto-native sources of capital for RWAs because what users want and the products offered are quite different. - Users want volatility. RWAs offer stability.

Between the countless hacks in DeFi and regulatory risks founders face while building in the space, I believe enterprise chains (like Onyx) offer an alternative that may scale faster. They combine all of the functional elements public blockchains enable, like transparency and speed, with what banks already have. For founders building financial primitives, enterprise chains could offer more scale than DeFi could in the next five years. It may feel like a far-fetched statement, but it is beginning to become apparent.

For instance, an RWA product like Centrifuge could list its loans on Onyx and benefit from the network of investors on these wealth management platforms. Or a private equity firm could tokenise portions of a publication like The Block and syndicate accredited investors. In the distant future, there could come a time when ESOPs can be tokenised, transferable and traded through brokerage accounts that settle directly in your bank account.

It is quite likely that banks release a “safe” or “compliant” version of DeFi protocols in a permissioned environment. One example of this in the wild is that of Aave’s institutional product. It connects some 30 institutions to one another in a permissioned lending pool. Another example, is that of banks tinkering with stable coins. For instance, JPM Coin (yes, that’s a thing), recently settled over $1 billion in transaction volume daily for partners.

Can such a system rival SWIFT network? It is quite hard to suggest it would. SWIFT benefits from decades of entrenched network effects. But systems like Onyx could see meaningful transaction volume within a few years. The efficiencies of speed and cost it offers, could onboard an increasing number of businesses to such solutions.

At some point in time, banks may want to settle certain types of transactions on a public blockchain like Ethereum if immutability is a requirement. Much like we see with L2s, they may conduct large parts of the transaction on their internal, permissioned environments and have finality on a public blockchain.

None of these applications are permissionless or censorship-resistant. Banks can boot users whenever they wish. They could have faulty compliance software that flags users and seizes their assets at will. The model I suggest above has nothing to do with what Bitcoin or Ethereum was built for.

For a good number of founders, building fintech applications that scale, matters more than decentralisation. They have every reason to tinker with enterprise blockchains, especially if regulators like MAS (Monetary Authority of Singapore) create sandboxes for such use cases. Ultimately, founders want the best technology that fits the use case. Sometimes, it is AWS. Sometimes, it is Ethereum. Maybe, in the future, it could be an enterprise-chain run by a bank. Who knows.

Suits vs Hoodies

All of this is not to imply that enterprise variations of blockchains are a guaranteed success. There have been attempts since at least 2014. The appetite for risk, especially for enabling new financial instruments whilst taking on the scorn of the regulator for little-to-no profit margin, may not be high at banks.

But what we see with this PoC is one instance of how blockchains are evolving beyond what we are used to.

If JP Morgan can make a small portion in revenue (say 0.01%) for every transaction through such a system, they have every incentive to scale it. By their admission, they have enabled some $900 billion in transaction volume for tokenised US treasuries on Onyx. That would be some $90 million in additional revenue if they could charge the small fee mentioned above. Is that large enough on its own? Not really. But keep in mind that these figures scale exponentially.

According to the report, the PoC created by JP Morgan can help reduce the operational aspects of handling 100,000 clients from 3000 steps to a few clicks. They don't talk about how settlements for these instruments would look like. But I presume it could be better than the T+2 settlement times equity markets have today. That speed efficiency could translate to better capital efficiency as the assets could be reinvested.

But change takes time when large enterprises are involved. For instance, a consortium of banks is trying to replicate what Google Pay and Apple Pay do. Quite late, I would argue. In the early 2020s, much of our ecosystem was looking towards Libra (Facebook's consortium of enterprises) as the new blockchain standard. It died a sad death.

The number of people coordinating on how risk is taken and the politics that play out while those decisions are made makes enterprises the wrong place for great ideas. (I may have annoyed future sponsors by saying that out loud). So, it remains to be seen if there can be large-scale impact in terms of blockchain adoption through enterprises with all their resources and distribution.

I don’t know if such blockchain standards focused on enterprise interoperability would take off, but I would argue that a class of use cases will require robust compliance in the coming years. A handful of enterprise chains are evolving to be better places to build, given the scale of the institutions developing them and the ease of staying compliant while making on them.

Founders have good reasons to explore them before writing them off if decentralisation and censorship resistance are not the core focus of their products.

Off to a friend’s wedding,

Joel John

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

- Podcast Episode : Sunny from Osmosis