Revisiting The Metaverse

Feels Meh, could get worse.

Hello!

Today’s article is part one of a two-part series examining the past and the future of Metaverse projects. In this issue, I explain why metaverse projects in Web3 have struggled to retain value. In the next, we will be looking at the approaches an emerging game from South-East Asia is taking to solve for user retention and monetisation.

In 2021, mentions of metaverse in corporate earnings calls reached a new height, with 170 firms mentioning it over 500 times at its peak. A report released a year later by Gartner showed that 64% of enterprise clients believed that the metaverse was mostly hype.

Over the past few days, I have pondered whether the metaverse is dead. Part of the reason is that I have been reading Neil Postman’s Technopoly. The book argues that the tools we use shape human culture as much as we shape the tools we use.

In 1440, when Gutenberg released the printing press, he could not have known that his invention would fuel the Protestant Reformation in 1517. The monks who developed the clock might not have realised they were laying the foundations for a time-based capitalist economy.

The metaverse – like the radio, internet, television and books – is a medium. It is a tool that is so new that we barely know the impact it can have on human culture. We had a hype cycle in the recent past because human attention was funnelled into new digital mediums during the pandemic. Games, social networks and even Zoom were in the limelight during the pandemic days. And as a portion of that attention went towards on-chain assets, we presumed it would continue to be a hot sector.

Before I tread any further, I should lay some basic definitions of the terms I will use throughout this piece. The metaverse, in the context of Web3 native apps, has historically referred to platforms like the Sandbox or Decentraland. These virtual worlds allow you to own assets represented as NFTs and build immersive worlds around them. The core use case of a blockchain in these platforms was to track asset ownership or enable payments.

But the metaverse is nothing new. If seen as a graphical interface through which humans interact, metaverses have existed since the early 2000s. For instance, MIT wrote about how Second Life enabled a parallel economy for gamers as early as 2007. Much of the discourse around the metaverse today is dominated by two firms:

Meta, which owns some 47% of the market share for VR devices and

Roblox, a platform that made $680 million in revenue last year alone.

For this piece, we will first dive into the state of the metaverse in Web3 and then zoom out and look at what has happened with the narrative over the past few years.

What Went Wrong

In 2022, metaverse real estate was so hot that JP Morgan had purchased a plot for itself on Decentraland. As of this writing, there are ~30 unique land traders for the three leading metaverses daily. Volume has dwindled from $17 million to a mere $50,000 today. For a sense of scale, in 2022, a single person paid nine times that amount for a single plot of land next to Snoop Dogg’s plot.

Today, the combined market capitalisation of real estate assets is a little over $250 million. Even when measured in ETH terms, lands on Decentraland and the Sandbox have dropped 90%. According to data from BinaryBuddha on Dune, the average volume of metaverse assets is down over 98%.

Some things must be made clear before we continue. Given that price and volume are a function of the market's state, I don't want my mentioning the metrics to be an interpretation of what I think of the team—my commentary on what went wrong critiques the sector itself, not the individuals or teams behind it.

With that out of the way, what went wrong? Much like DeFi, NFTs (and metaverse assets) were heavily dependent on the flow of liquidity from existing assets like Bitcoin to risk-on assets like NFTs. Given that the supply of NFTs (like Bored Apes) or land was low, assets with capped supplies saw a substantial uptick in their value for short periods. But they could not retain that value for long because nobody built sticky experiences within these virtual worlds.

One parallel to draw here is that of a city. Properties in a city are expensive if one of two things happen:

Local legislation makes owning property there profitable for tax, immigration or commerce-related reasons.

There is a massive influx of individuals to the city, so an increasing number of people want to avail a scarce asset.

The digital land boom went bust because we never optimised for masses coming to our virtual worlds. Between setting up wallets, acquiring tokens and trying not to get hacked or scammed, individuals spending time on metaverse properties dwindled rapidly. The few remaining were traders looking to make a quick buck by being early to the asset class. As the price (and interest) of the properties they held in these virtual worlds declined, so did the speculators’ interest in them.

The broader ‘miss’ we had in the last three years is the obsession with the idea that Web3 is all about ownership. In our pursuit of decentralising governance (whatever that was) and ownership, we forgot that gamers strive for something simple: fun.

We never had a large enough userbase of Web3 native gamers, which was challenging due to the friction associated with crypto native rails. Would you rather download a game on XBOX and get into gaming or go through the hassle of sending your passport to a strange exchange in your country?

These challenges are now solved through on-ramps like TransFi that aggregate regional payment methods. In such a model, a gamer could come through any regional payrails and access instant payouts from a game using crypto. Naturally, such a model would only take off in emerging markets where payment rails are not strong enough, and the premium for buying crypto is as high as 10% compared to local currency.

Motives and Retention

Fun could not be prioritised because these virtual world products had short development cycles and relatively small budgets. For context, the large AAA titles we consider to be ‘successes’ needed between $80 to $250 million to launch. The metaverse as we know it was built by firms that had raised seed rounds in 2019 and were building along through the worst phases of the market.

Profit motives were the only immediate incentives most traders (and users) had in these apps at the time. They gave up fun for the sake of ‘money’. However, if you study the academic literature on the motives of gamers, particularly regarding what makes free-to-play gamers convert to paying gamers, you see why the model broke.

In the early 2010s, the economics of gaming changed drastically. The rise of affordable Android devices meant that increasing numbers of people were open to gaming but were unwilling to pay for it upfront. How do you monetise such a crowd? You onboard them with no upfront payment and sell them items via micro-transactions. In 2020, a paper studied the motivations behind why gamers pay in such applications by summarising the results from 17 different research papers.

The table below indicates their findings. There is a recurring theme you’d find. Socialising, enjoyment and competition are the crux of what made those games desirable for users.

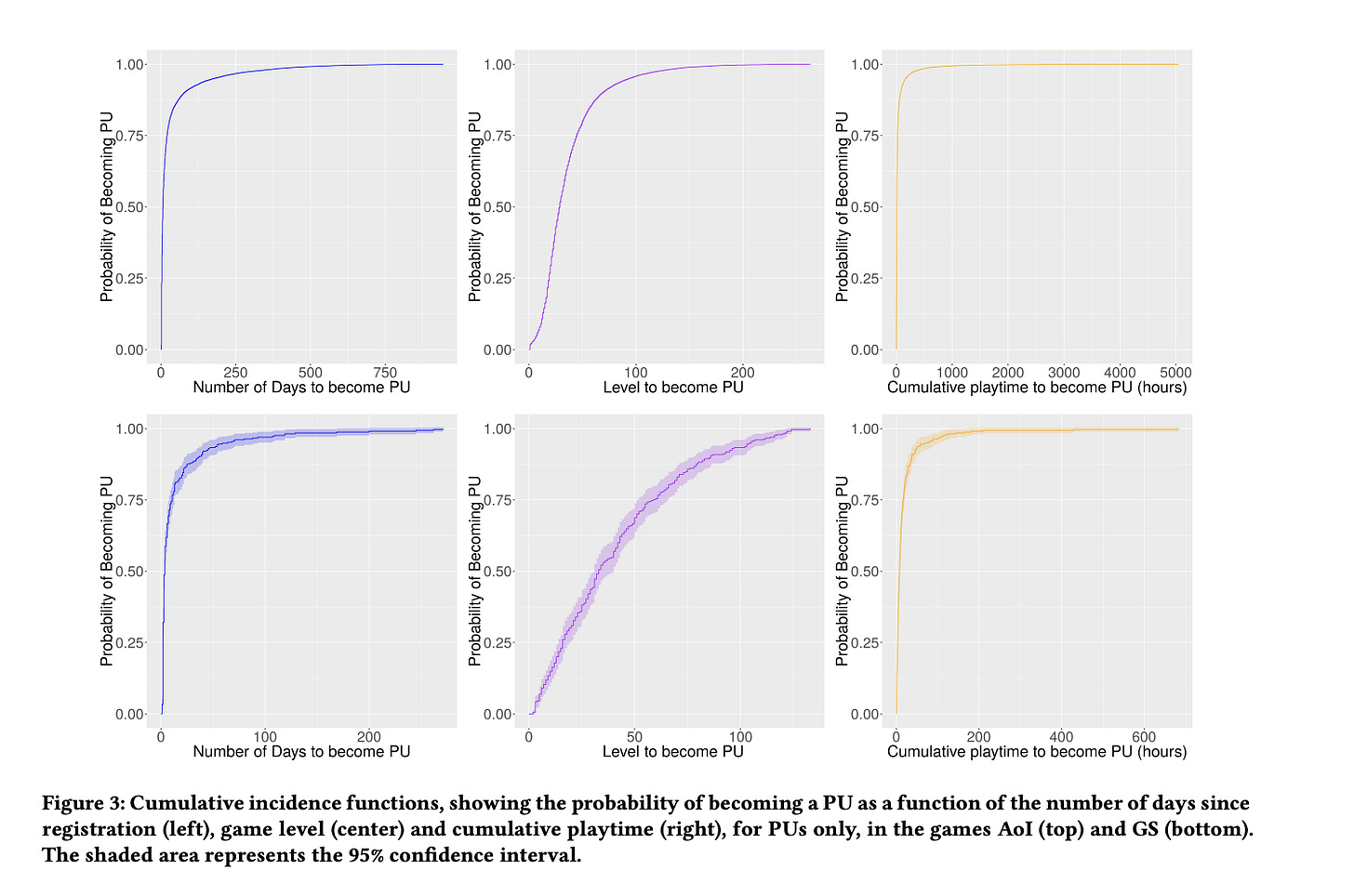

We were kicking the can down the road: “There were no users, so the platform died.” It’s a relatively simple argument to make. So, I studied how long it takes to convert gamers to paying users. A different study examined the probability of a user converting to a paid user on freemium games. The data below considers the likelihood of a user becoming a paid user depending on their level in the game, number of days played and cumulative playtime. The data sets are for two games - Age of Ishtaria and Grand Sphere. As you can see, in the free-to-play world, it takes hundreds of hours and weeks of player retention for a gamer to convert to a paying user.

This combination of an extremely low entry barrier and sticky user behaviour powered the free-to-play economies of the past. At least some of my readers will think this is an apples-to-oranges comparison. The metaverse, as we know it, is not about onboarding users. It is about enforceable scarcity and verifiable ownership. But our obsession with enforcing scarcity alone cannot sustain the markets. Consumers need and demand more.

My point is that the metaverse, as folks in Web3 consider it, didn’t take off for several reasons. We thought that artificial scarcity and speculation would be permanent trends. It turns out they aren’t. We believed trader personas would stick around in a bear market. It turns out they don’t. As their portfolios of altcoins sank, their risk appetite declined. They had no reason to continue spending their time in our versions of virtual worlds.

We thought that obsessing about expanding the user base did not matter as metaverse games have higher revenue per user. However, a considerable part of the motivation for gamers is socialising and relative rank. High-priced NFTs help with signalling (and establishing rank), but in the context of games, it is the equivalent of pay-to-win.

Gaming markets are increasingly specialised in that marketplaces, game design, payment rails and a game’s management are increasingly separated and compartmentalized. When Web3 native metaverses took off, we expected firms that were at Series A levels to be able to tackle all of the above simultaneously. Founders had to scramble to solve issues ranging from collapsing in-game economies to developing fiat on-ramps to expand their user bases.

I believe it is nearly foolish to think that the metaverse in Web3 will take off in 18 months. Rockstar Games had decades of game-building experience before GTA 5 took off. To expect Web3-native firms to be able to establish a sector and retain users in the span of a single market cycle is akin to filling a car with jet fuel and hoping it will land on the moon.

Zooming Out

It is not only the Web3 version of the metaverse that struggled to find PMF. All forms of it have experienced an uphill battle. Meta has lost more than $21 billion in investing in the metaverse as a concept. Much of it went to hardware research, but until recently, the avatars in their Quest devices barely had legs. Even today, the hardware costs $500 and is beyond what is affordable for much of the world. Enterprise interest in the metaverse has waned rapidly as AI becomes the hot new thing.

While researching this piece, I wondered what venture investors were thinking when they presumed users would flock to virtual worlds at scale. Why did researchers (including myself) think we had crossed the chasm with the metaverse? Which person, in their right mind, would think commerce, love and education would happen through graphical interfaces? We were all excited about a new medium. And there is likely a part of us thinking that, much like the internet, this new medium would make the world more equitable and accessible as we would no longer see people for their real-life identities but just as virtual avatars.

Whenever a new medium comes around, it takes decades before it changes society. The printing press was invented in the 1440s, but it took until the Protestant Reformation of 1517 for it to enter wider usage. It took a few more centuries before the general peasantry could read. So not only did you need a hardware upgrade (the press), but you also had to wait till humanity synced with this new firmware release (the skill of reading).

Similarly, television took the world by storm in the 1950s. But it was not until the 2010s that short-form video content became mass-produced by everyone. The medium existed for decades but disrupted the world through TikTok and cat videos decades later.

For this new medium (the metaverse) to take off, we will need an increase in network bandwidth, a decline in hardware costs and a shift in cultures. Apple’s Vision Pro is a step in that direction. Meta, in collaboration with Rayban, recently launched a headset resembling the Google Glass from the mid-2010s. It uses AI to overlay graphics onto your glasses so that you can interact with the world world through Meta’s hardware. However, we don’t yet know whether consumers will embrace such devices.

Meta’s virtual world, Horizon World, had over 900 users a few weeks back. This is a trillion-dollar firm that has spent billions of dollars on hardware and is struggling to retain over 1,000 users. The product has barely managed $10k in transaction volume. In 2022, Mark Zuckerberg's goal for the virtual world was to have more than 500k MAUs. They are at *checks notes* 0.18% of the way there. Despite Meta's tremendous distribution across WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram, they have struggled to onboard users.

It's safe to say that Web3 teams won't have much luck in comparison. Meta has a history of acquiring assets or spending heavily on experiments for outsized returns. They spent over $19 billion on WhatsApp and another billion on Instagram. Both of which have yielded outsized returns.

The metaverse is an evolving oncept, and it is easy to obsess about how little (or how much) has been done with it. One of the things a developer friend (named Suzu), who has been on the internet since the 1990s, mentioned while discussing this piece is that developers working on the metaverse in crypto are trying to make a Biriyani Lasagna. These are beautiful, useful things when kept separate. But in force-fitting them with one another in ways that don’t blend well, we create worse-off products for users.

Founders and investors often ignore the beauty of communities (like Second Life, GTA 5 or Red Dead Redemption) - and argue that a Web3 native metaverse could replace all of them. One way to fix this would be to mandate that Metaverse experts spend real time in the worlds they are designing.

If you think of the current forms of the metaverse – like Roblox, Fortnite or Apple’s VR devices – we already have functional worlds where people spend billions of hours. They don’t spend all that time and money wondering if they own these worlds. They spend their time there because they have fun.

We need to take a few steps back and consider what it would take to bring a million users into a metaverse. All commerce requires human attention. We obsessed too much with ownership and governance while conveniently forgetting what it would take to accumulate and hold on to human attention in a world where TikTok, Roblox, and ChatGPT compete for attention.

Next week, we’ll study how a game from India is trying to solve challenges in acquiring and retaining users in the Metaverse.

Off to work on the week’s long-form article,

Joel John

If you liked reading this, check these out next:

Joel: Casually dropping a truth bomb dropped on the entire industry. But here's the thing, I feel that the piece is based on the presumption that PMF will be found in gaming first. What if pilgrimage picks up? Or just another Social media? Orv something that we haven't even imagined?