Orchestrating Flow

How LI.FI Breaks Walls

Hello!

Base just announced it's moving away from Optimism's OP Stack to build its own architecture. OP is down almost 25% in a day after the largest source of revenue for Optimism chose not to pay them anymore.

We didn’t know about this when we started writing the article, but we made the case for further fragmentation in crypto. Fragmentation at the level of chains, token standards, and liquidity. Over the past few weeks, we have been working with the LI.FI team to make the case that fragmentation in crypto is not a temporary phase. Base walking away just proves the point.

If you are building across chains, trying to bring all of crypto together, write to us at venture@decentralised.co.

TLDR:

Complex systems have a tendency to fragment before they consolidate. Telephones got automatic switches. Banks got clearinghouses. The internet got TCP/IP, then search engines. Crypto followed a similar path. The industry expanded into a landscape of L1s, L2s, and app chains; bridges and DEXs now connect them. But the problem is that delivering an outcome still depends on multiple independent services behaving correctly in sequence.

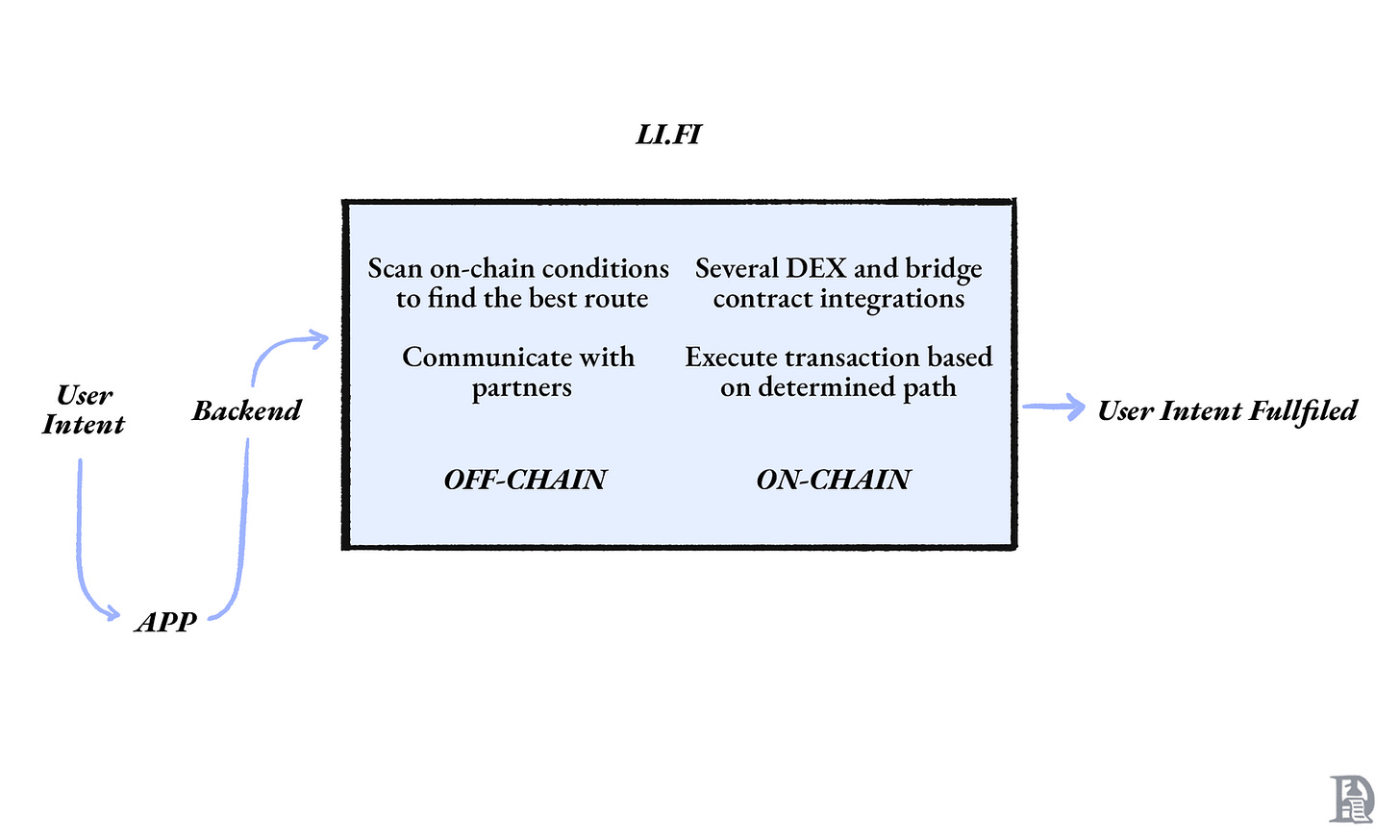

LI.FI is an orchestration infrastructure for this problem. It distils cross-chain complexity into composable building blocks that developers can combine to build the flows their products require.

Three shifts make this timely.

Fragmentation is compounding

Regulation is driving more fragmentation.

Execution is becoming autonomous.

In a world of increasing asset and liquidity fragmentation, the winners will be systems that can scale with the complexity of orchestrating the steps needed to fulfil users’ needs.

Almon Brown Strowger was a mortician in Kansas City, Missouri, USA. His legend goes like this. Strowger was losing business to his competitor. He was convinced that his competitor was getting all his orders thanks to his wife, who worked in a telephone switching company. In 1891, Strowger built a device that would route calls without human intervention.

Whether the conspiracy was real or not, Strowger’s response changed telecommunications. A caller would express their intent (the number they wanted to reach), and the switch would figure out the physical path through the network.

Before automatic switching, every call was a negotiation with the phone operator. You waited to talk to the other person because the operator physically connected the wires. As networks grew, operators became bottlenecks. The complexity of possible connections outpaced human coordination capacity.

The switch absorbed routing into the network itself. Instead of expressing an intent to a human intermediary, the caller dialled, and the system connected. This provided a much better user experience.

Lasting complex systems tend to follow this path. When they grow beyond what individuals can coordinate on their own, coordination shifts to systems designed to manage it at scale.

We have seen this pattern repeated across communication, banking, and modern food delivery apps. The Internet itself was not immune to the problem of scaling. We are also seeing this play out with blockchains. Blockchains are about making distributed computers independently agree on a version of the truth. The fewer things they have to agree on, the better. This is why blockchains are closed worlds. Something is needed to coordinate how value and information move across these closed systems. Bridges were the first step towards this coordination.

This article examines how increasing fragmentation creates orchestration bottlenecks, how LI.FI is improving the user experience across several blockchains and is shaping the interoperability (interop) space as more and more global finance shifts onto blockchain rails.

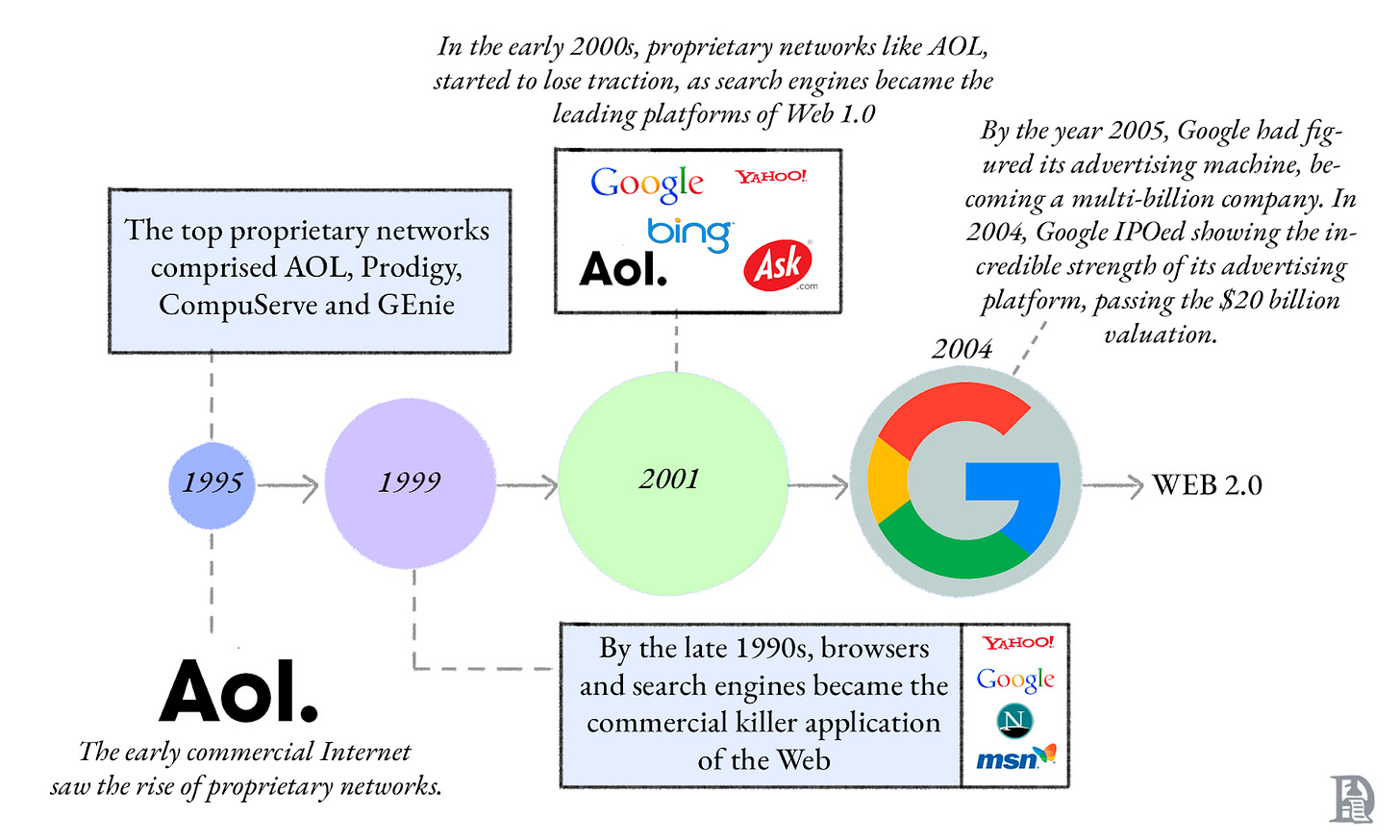

Multiple Networks to One Internet

The Internet grew out of many small, purpose-built networks run by universities, research labs, and government programmes, each solving a local communication problem rather than trying to coordinate globally.

Until the early 1980s, computers were connected through shared institutional systems and research networks where access was limited, connectivity was intermittent, and communication depended on telephone infrastructure. These networks worked, but they were expensive and not designed to interoperate by default. As the number of networks grew, coordinating between them became more difficult.

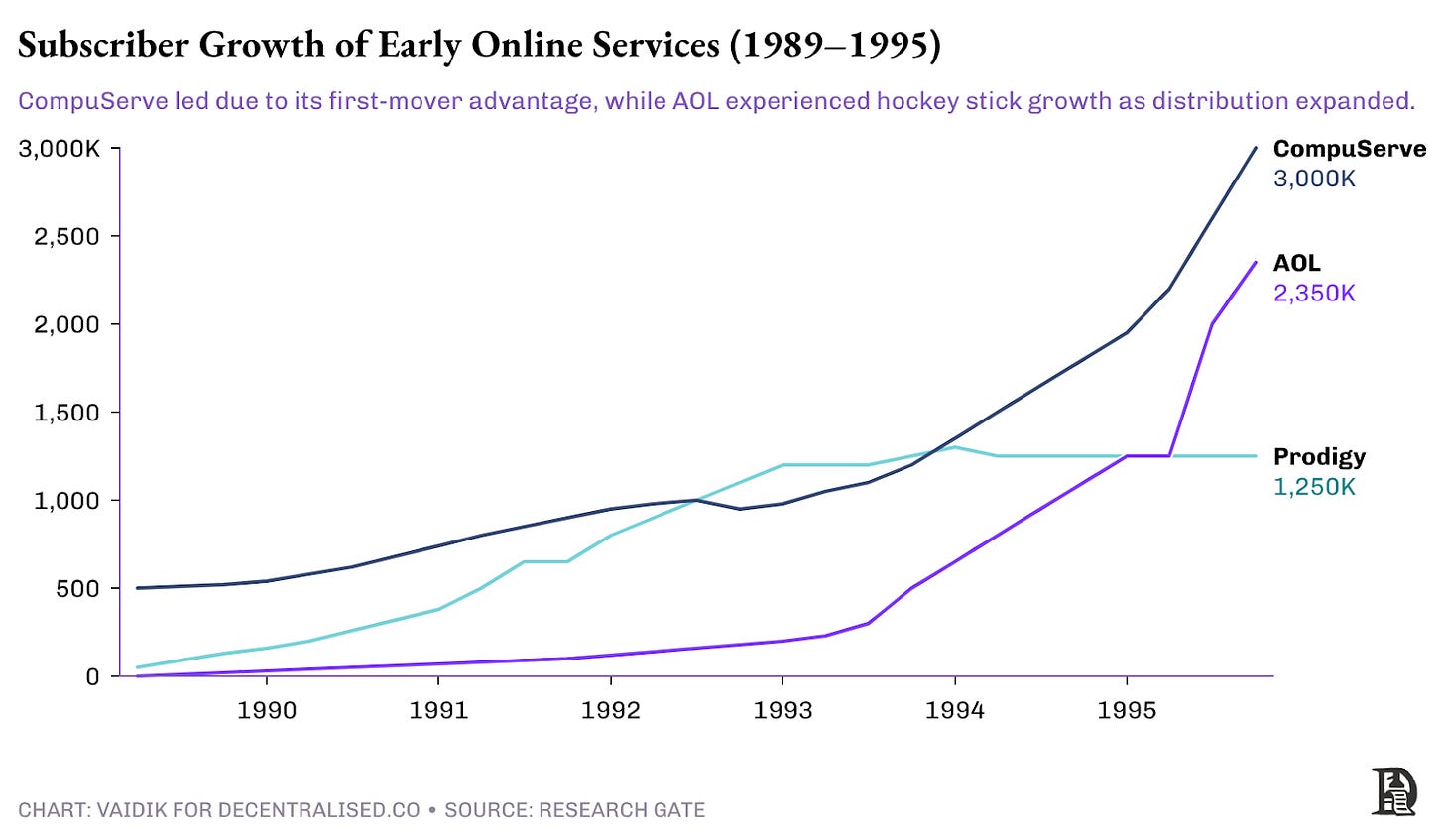

CompuServe, AOL, and Prodigy each operated its own network. Users subscribed to one service, logged into that service’s servers, and interacted only with other users and content inside that network. Communication across services was not supported.

From the user’s perspective, this meant that “being online” did not mean accessing a global network. It meant choosing which system to subscribe to. Content did not flow freely between services. Messages sent on one platform were invisible to users on another. There was no shared discovery layer, no shared messaging standard, and no shared economic rail.

Crucially, this problem could not be solved by any single platform growing larger. Even as AOL scaled rapidly, it remained incompatible with other services. Growth improved coordination within a network, but did nothing to reduce coordination costs between networks.

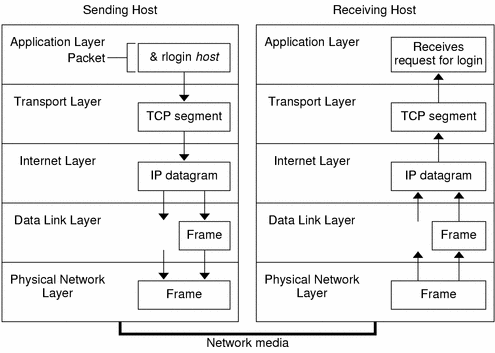

The breakthrough came by standardising how data moved between machines rather than trying to standardise user experience or consolidate platforms. This led to the development and adoption of TCP/IP, a set of transport standards that defined how information could be addressed, transmitted, and reassembled across heterogeneous networks.

It allowed networks to retain their internal structure while conforming to a shared set of transport standards. Systems no longer need custom, bilateral integrations to exchange data. As long as they followed the same protocol rules, packets of data could move reliably between otherwise incompatible networks.

When communication between networks was standardised, the system could finally scale beyond bespoke integrations. Standardised transport created a shared substrate on which independent services could be built and reached reliably, even though those services were not coordinated with each other.

What was the impact of this? If there are three separate networks, you need at least three custom integrations to enable them to communicate with each other. For four networks, you need six custom integrations. Ten integrations for five networks, and so on. Statistics nerds know that it’s NC2 custom integrations for N networks or systems. So if 100 different businesses wanted to exchange data, they would have needed 9,900 custom integrations. TCP/IP eliminated that need with one shared standard.

However, this did not make the Internet easy to use by default. As more organisations began publishing information and building services on top of shared protocols, the number of reachable destinations grew faster than any individual could reasonably keep track of.

The problem was no longer whether systems could talk to each other, but how users decided where to go and what to interact with. Information was technically accessible, but discovery became expensive in human terms. Knowing which site mattered, which service was trustworthy, or where value actually lived required effort that did not scale with the network’s size.

Search engines, app stores, marketplaces, and media platforms emerged to solve this by making accessing the web easier. They indexed a rapidly growing universe of independent services, applied ranking and filtering rules, and routed users towards a small set of relevant options at any given moment. So, instead of picking from millions of unrelated options, users could choose from ten highly probable options.

Search engines did nothing to unify the underlying system. Websites and services remained separate, owned by different operators. What changed was how users discovered them. Instead of users having to reason about destinations, protocols, or addresses, these platforms absorbed that complexity. They handled discovery and access at the point of interaction, allowing users to focus on what they wanted to do, from finding information to consuming content, or completing a task, without having to think about how the underlying system worked.

Crypto has gone through a similar transition. What started as a single shared execution environment has spread across many independent chains, each with its own liquidity, rules, and constraints. The orchestration problems that shaped the early internet have returned, at the level of making actions actually complete across different execution environments.

How did Crypto Get Here?

From 2015 to 2020, most on-chain activity occurred on Ethereum. Smart contracts, liquidity, and users shared a single execution environment. Assets were native, and transactions entered the same mempool and were ultimately ordered by the same set of validators. Because everything lived on the same chain, composability was the default.

During the DeFi Summer of 2020, routine actions such as token approvals, swaps, and liquidity provisioning frequently cost hundreds of dollars.

Any burst of activity delays unrelated transactions across the network.

Alternative Layer 1s and rollups both emerged as responses to Ethereum’s execution constraints. L1s reduced fees by adopting different design trade-offs, while rollups improved throughput by batching transactions and settling back to Ethereum. New chains offered aggressive subsidies to bootstrap activity.

Users were no longer tied to one chain, so applications had no reason to stay on one either. Uniswap launched on Polygon, Arbitrum, and Optimism with largely identical core logic. Aave deployed across Ethereum, Polygon, Avalanche, and later other networks. The same applications now existed in parallel across different execution environments.

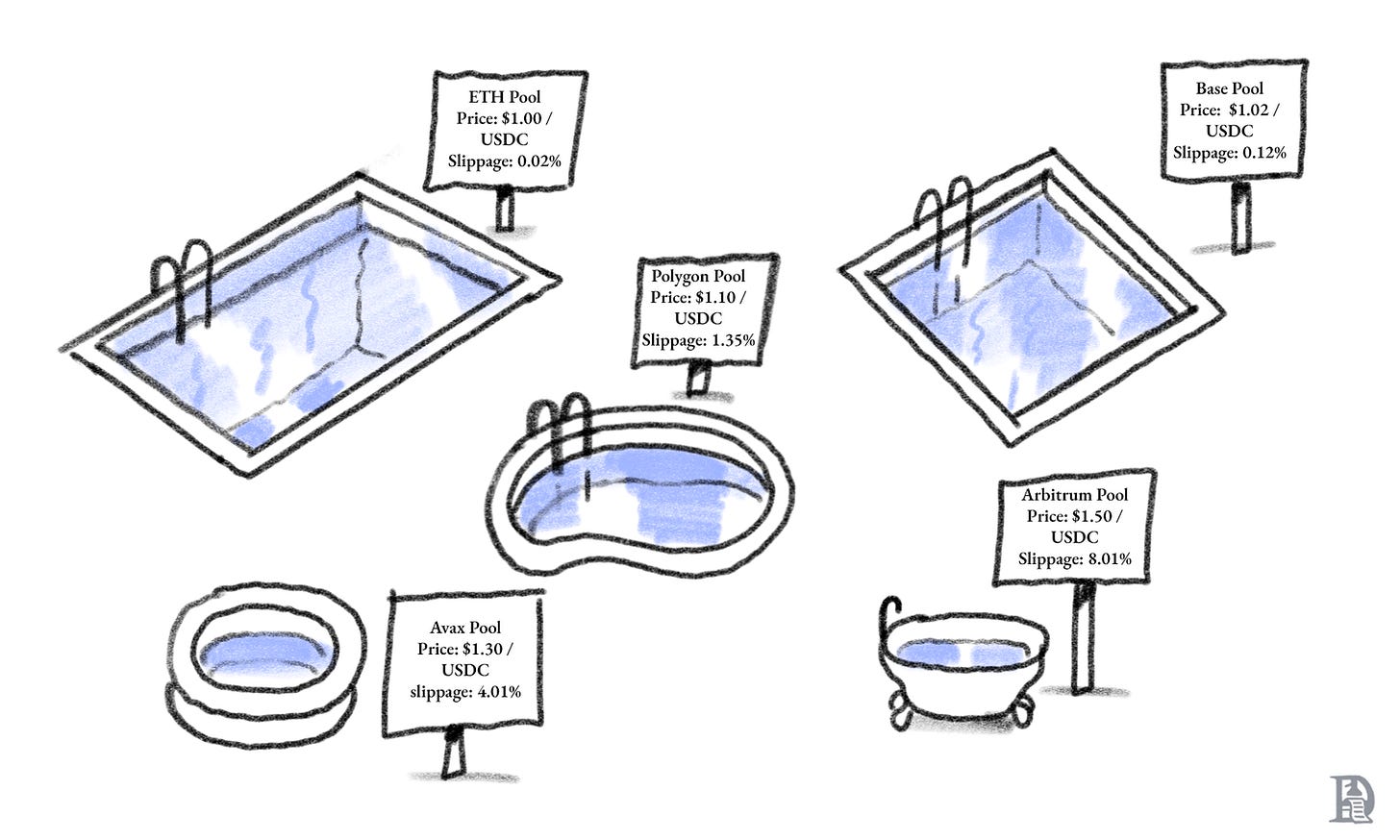

As assets moved across chains, the same token began to exist in multiple places at once. Stablecoins, ETH, and governance tokens were bridged into separate liquidity pools on each network. Liquidity that had once aggregated naturally on a single chain now sat in parallel pools with different depths and conditions.

This made prices less uniform. A token swap on Ethereum might clear at a different price than the same swap on Polygon or Avalanche, simply because liquidity was thinner or arbitrage was slower. During periods of volatility, users could see materially different outcomes for the same trade depending on where it was executed.

This fragmentation also extended beyond liquidity into the state. User balances, approvals, LP positions, and borrowing relationships were now distributed across chains. Actions that were previously atomic, such as moving collateral or rebalancing positions, became multi-step workflows involving bridges, with long wait times and repeated approvals.

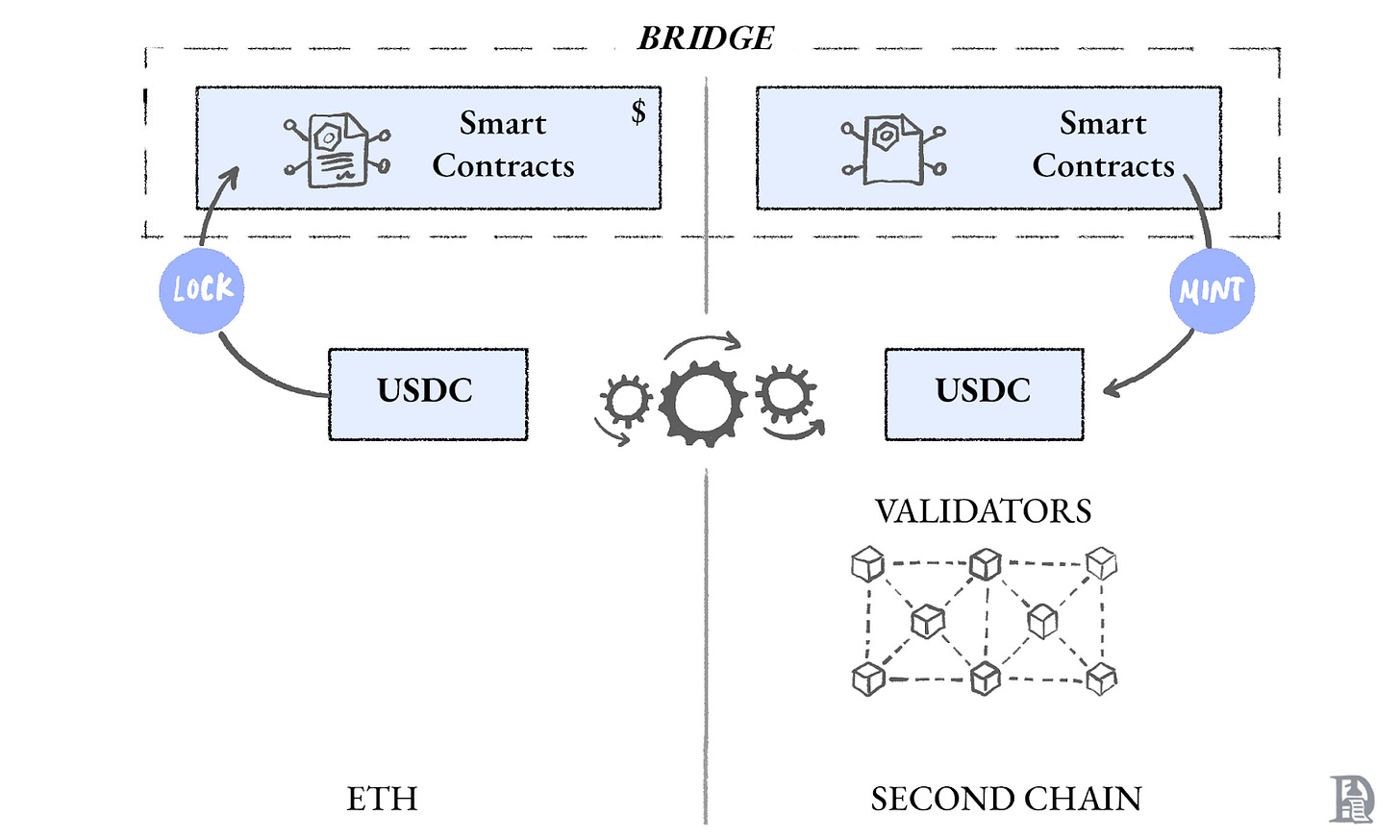

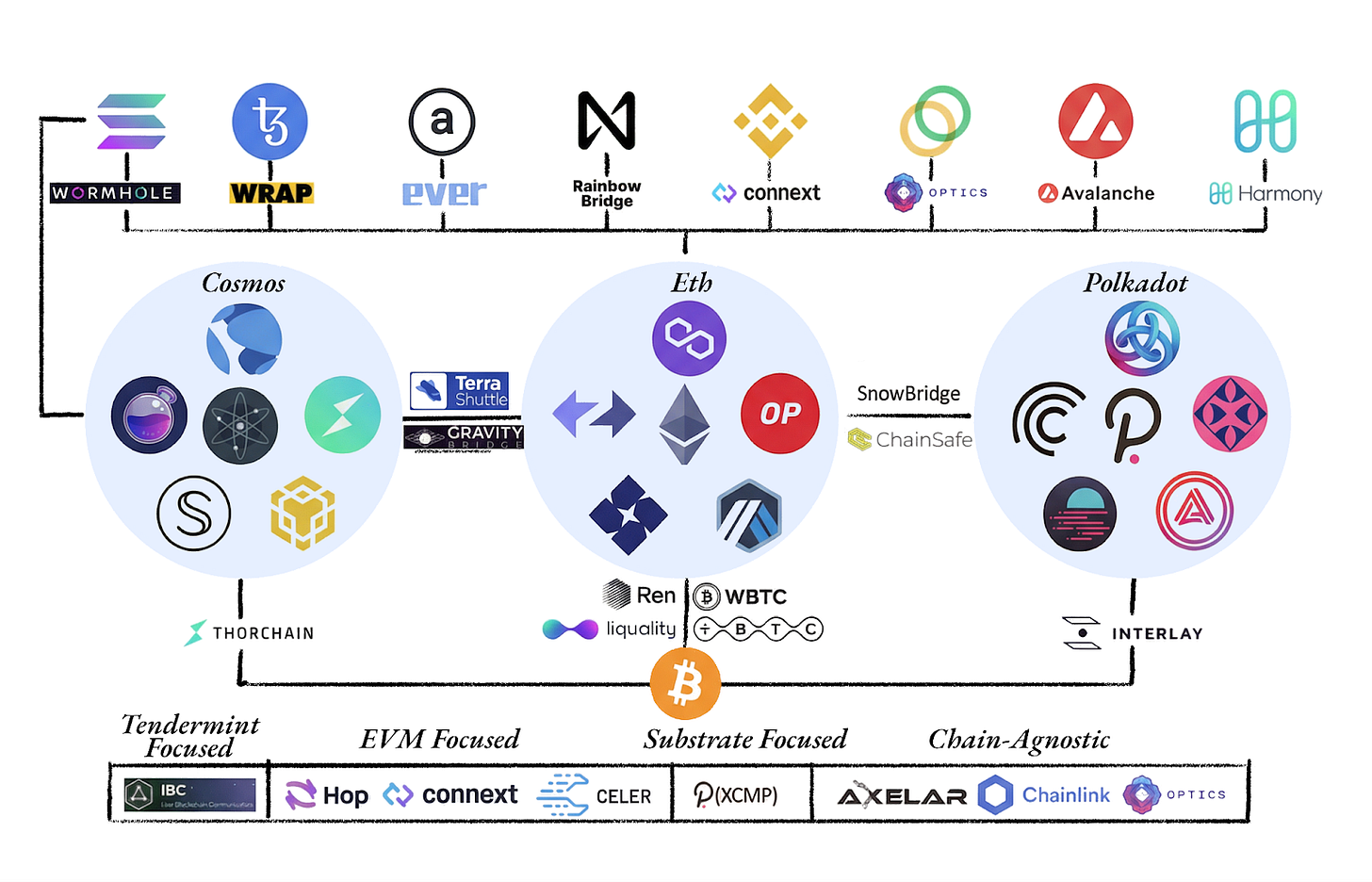

Bridges became the critical coordination layer. Unlike single-chain execution, bridges operate across separate security domains, relying on validator sets, multisigs, or other off-chain actors to authorise transfers. Compromising even part of this verification layer is sufficient to break the bridge, even if both chains remain secure.

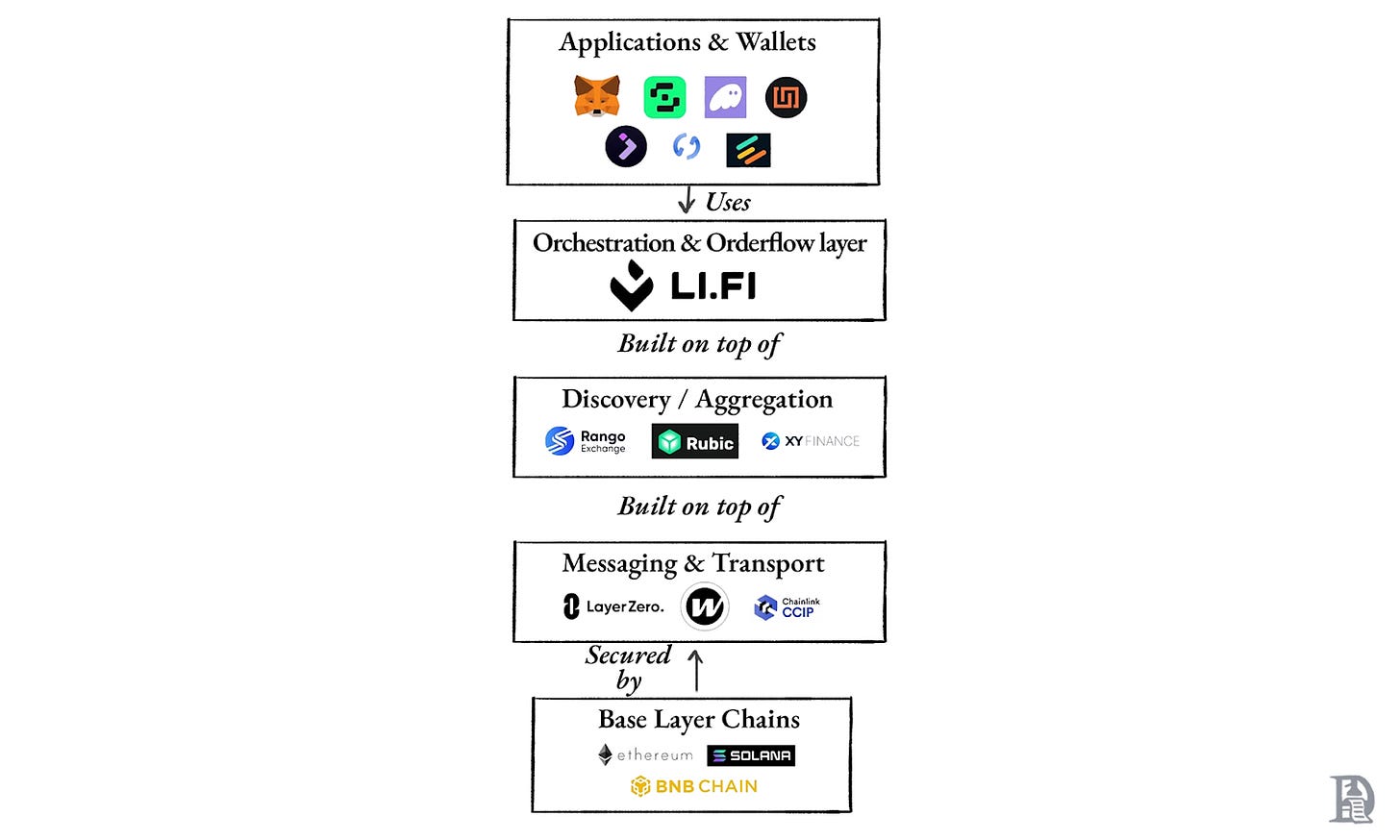

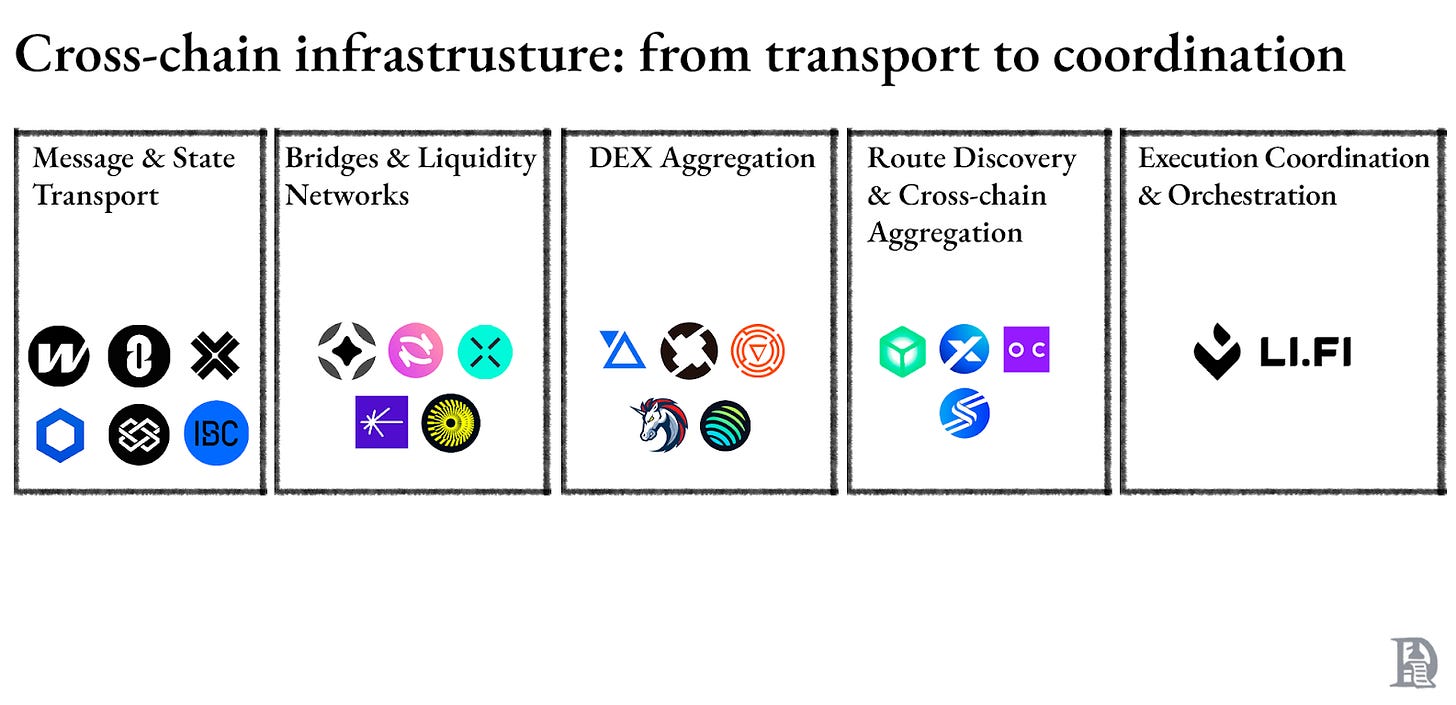

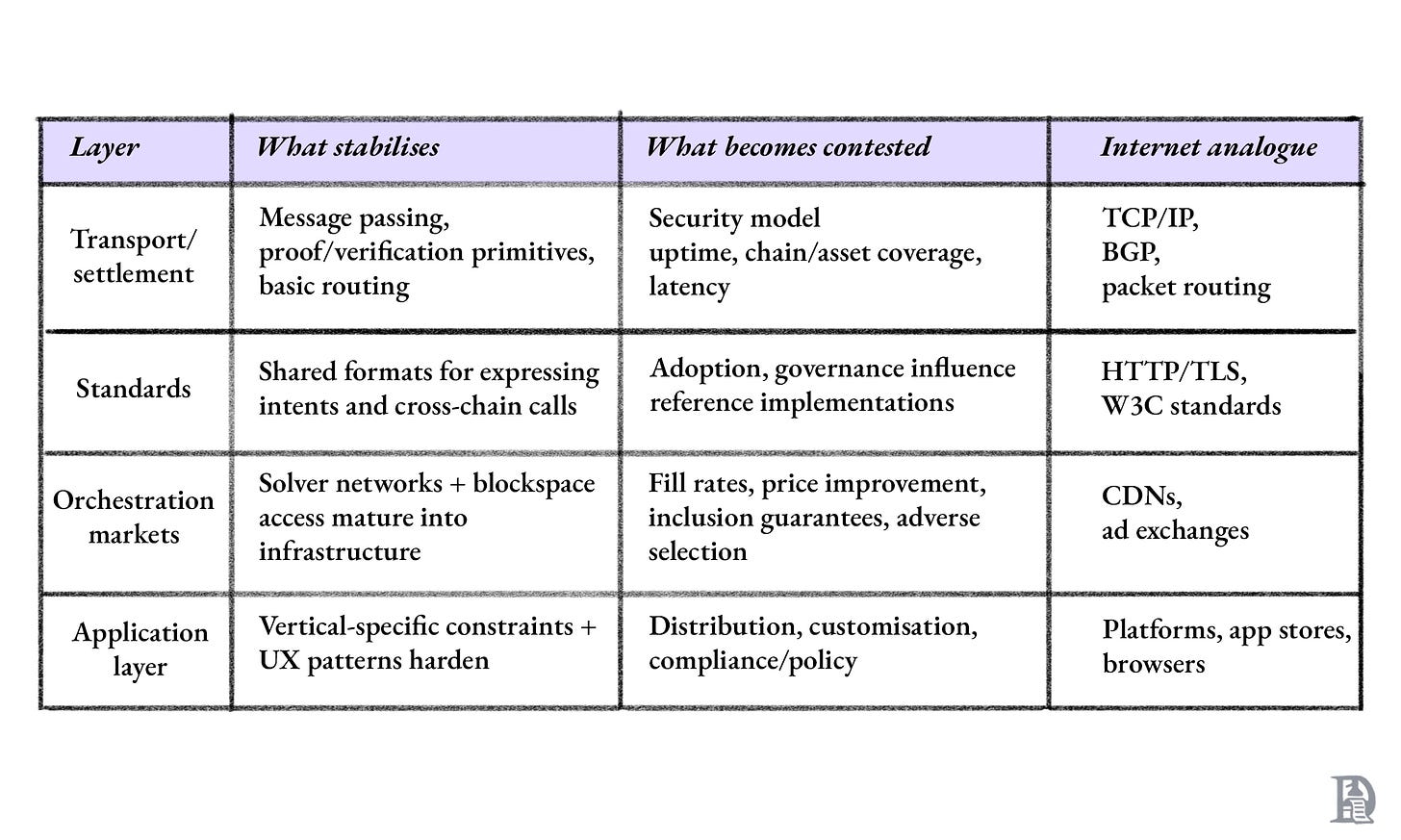

This is the point at which crypto’s interoperability stack began to stratify. What had been a single problem of “how do I move assets?” split into distinct layers.

transport (how messages and proofs move between chains),

standards (how intents and cross-chain calls are expressed),

execution (how orders are fulfilled), and a

applications (how users interact with all of it).

Each layer would evolve at different speeds and face different competitive dynamics.

At a high level, bridges enable assets and actions to be used across otherwise independent execution environments. Over time, two dominant approaches have emerged, reflecting different answers to the same question: how much of the cross-chain complexity should be pushed onto users, and how much should be absorbed by the system.

On the one hand, interoperability has converged around standardised token representations and mint-and-burn models, in which assets move across chains via shared token standards and messaging layers. These systems aim to make assets broadly portable and composable across many environments, but they still require applications and users to manage execution details across chains.

On the other hand, intent-based approaches have grown in prominence, where users specify outcomes and the system orchestrates how those outcomes are achieved across chains. Instead of exposing each intermediate step, these systems shift more responsibility to the infrastructure layer.

The aim here is not to delve into bridge taxonomy, but to understand their role in the orchestration layer. Their design choices shape how failures propagate, how liquidity is accessed, and how much complexity applications must absorb.

As execution spread across Layer 1s, rollups, and Ethereum itself, fragmentation began to compound. Each environment had introduced its own sequencer, block cadence, fee market, and operational risks. Gas mechanics added another layer of friction, as users frequently arrived on destination chains without the correct gas token to complete execution. Partial solutions such as gas sponsorships existed, but they were very inconsistent and application-specific.

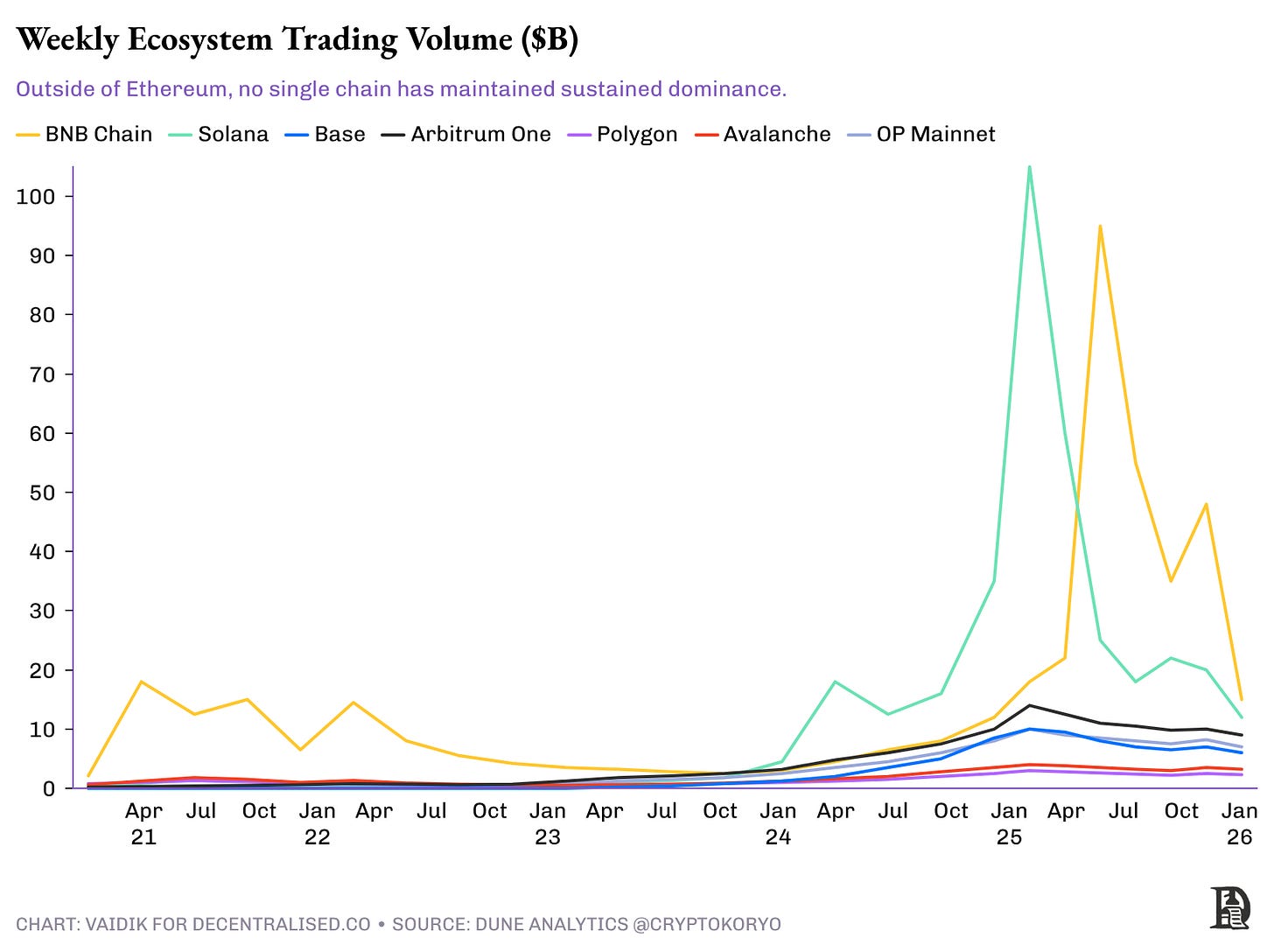

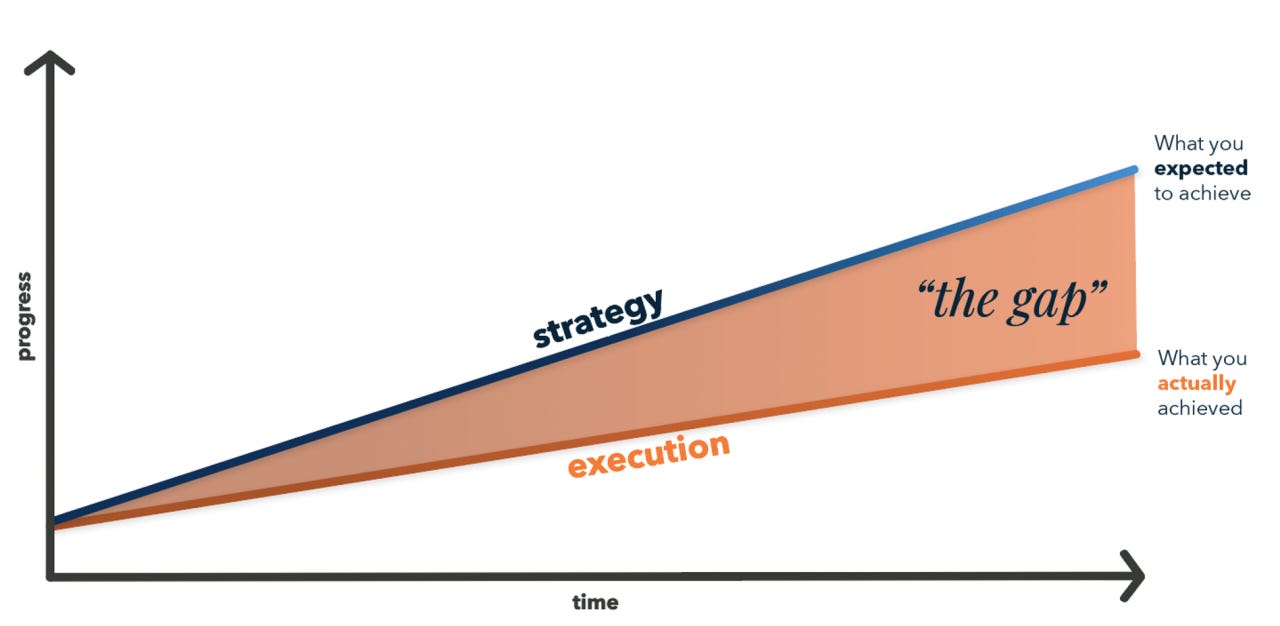

Teams took on this burden because blockchains were no longer just execution environments. They had become distinct markets. The chart below shows trading volume in different ecosystems. If you exclude Ethereum, there’s no clear winner. Applications could not afford to ignore other chains. Even if it were for a brief period, if your application were on a chain that attracted activity for any reason, you would stand to gain users.

Applications had a clear economic incentive to expand. Remaining on one chain meant leaving users, volume, and liquidity on the table as activity migrated elsewhere. Expanding to additional chains allowed applications to meet demand where it already existed, rather than trying to pull users back into a single environment. Put simply, if you stayed on just one chain, you left money on the table. Going multi-chain had become the table stakes.

That expansion came with significant operational overhead, but it was often the only way to maintain growth, relevance, and competitiveness in a system where usage was no longer concentrated in one place.

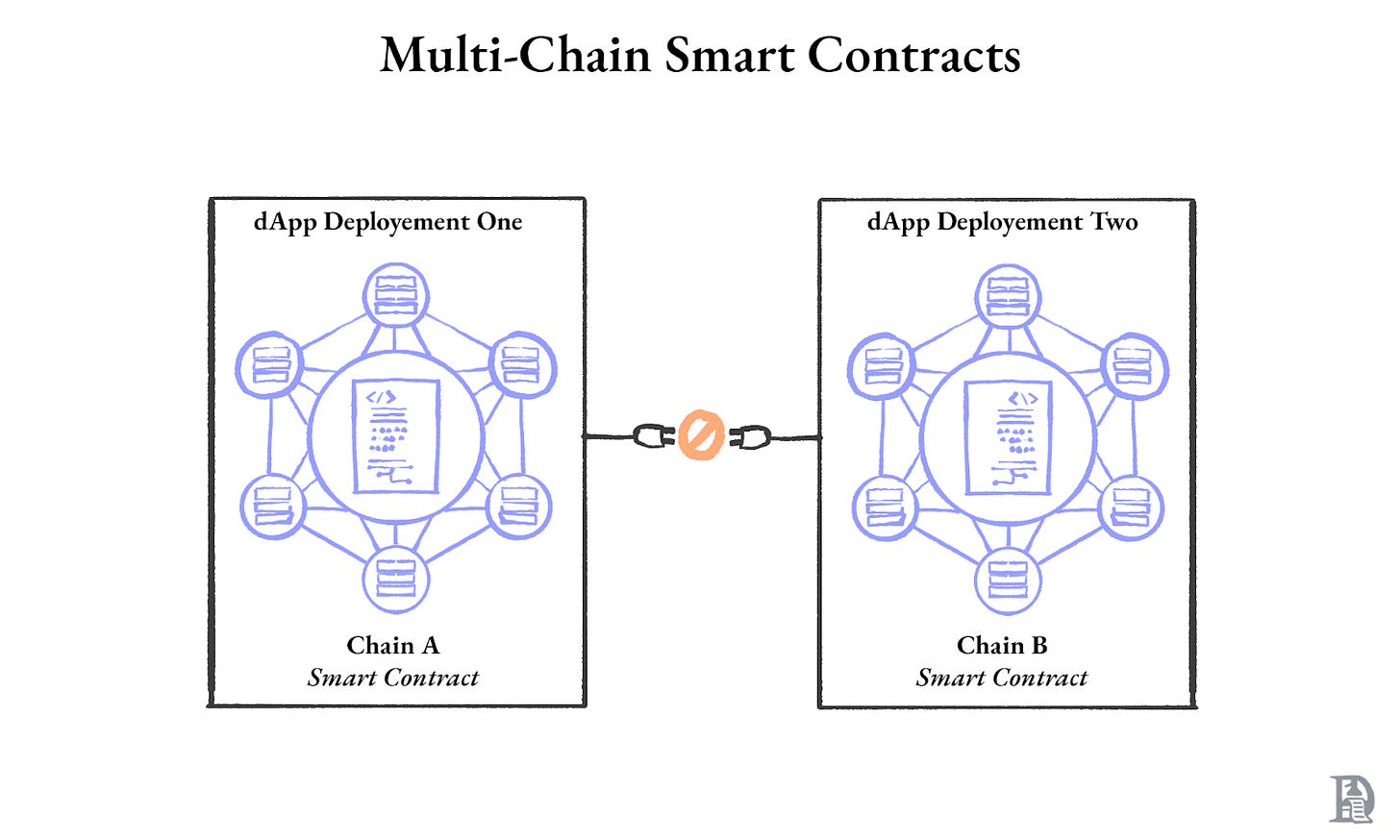

For developers, multi-chain execution dramatically increased operational complexity. Applications could no longer be deployed once and operated globally. Every network required its own contract instance, RPC providers, and indexers, and each introduced its own failure modes.

Moreover, this was not a one-time cost. Engineering teams repeatedly described multi-chain expansion as running the same application under different operational assumptions, requiring them to handle upgrades, monitoring, and incident response independently for each chain.

Before 1773, bank clerks physically walked across London to settle debts with every other bank. Every morning, dozens of clerks trudged through mud and cobblestones, carrying paper and coin, visiting every counterparty individually. As the number of banks grew, bilateral settlement became untenable because its complexity scaled quadratically.

The solution emerged in a coffeehouse on Lombard Street. Clerks started meeting at the Five Bells tavern at day’s end. Instead of settling bilaterally, they netted their balances. Dozens of physical journeys collapsed into one meeting. The clearing house separated what banks owed from how they settled.

Crypto today is in a similar spot, but the shape of the problem has changed. New blockchains no longer connect through simple, pair-wise native bridges. Instead, they launch already wired into the ecosystem via third-party liquidity bridges, interop token standards, and shared execution infrastructure spanning many chains. Connectivity is no longer the bottleneck.

The difficulty lies in composing actions across what is already connected. Capital can move, assets can be represented across chains, and liquidity can be reached from many venues, but every user action still depends on multiple independent systems working together. The complexity adds up in the same way it did on the streets of 1770s London.

Luckily, history offers a direction towards a solution. What is needed is not more bridges, but an orchestration layer that converges routes. Something akin to a Lombard Street for on-chain settlement, a layer that separates what users want from how it is executed. This is the gap that systems like LI.FI fill by providing a single integration surface where multiple execution providers (like liquidity pools, bridges, DEXs, fast paths, and intent-based systems) come together to fulfil actions across any chain.

The Aggregation Trap

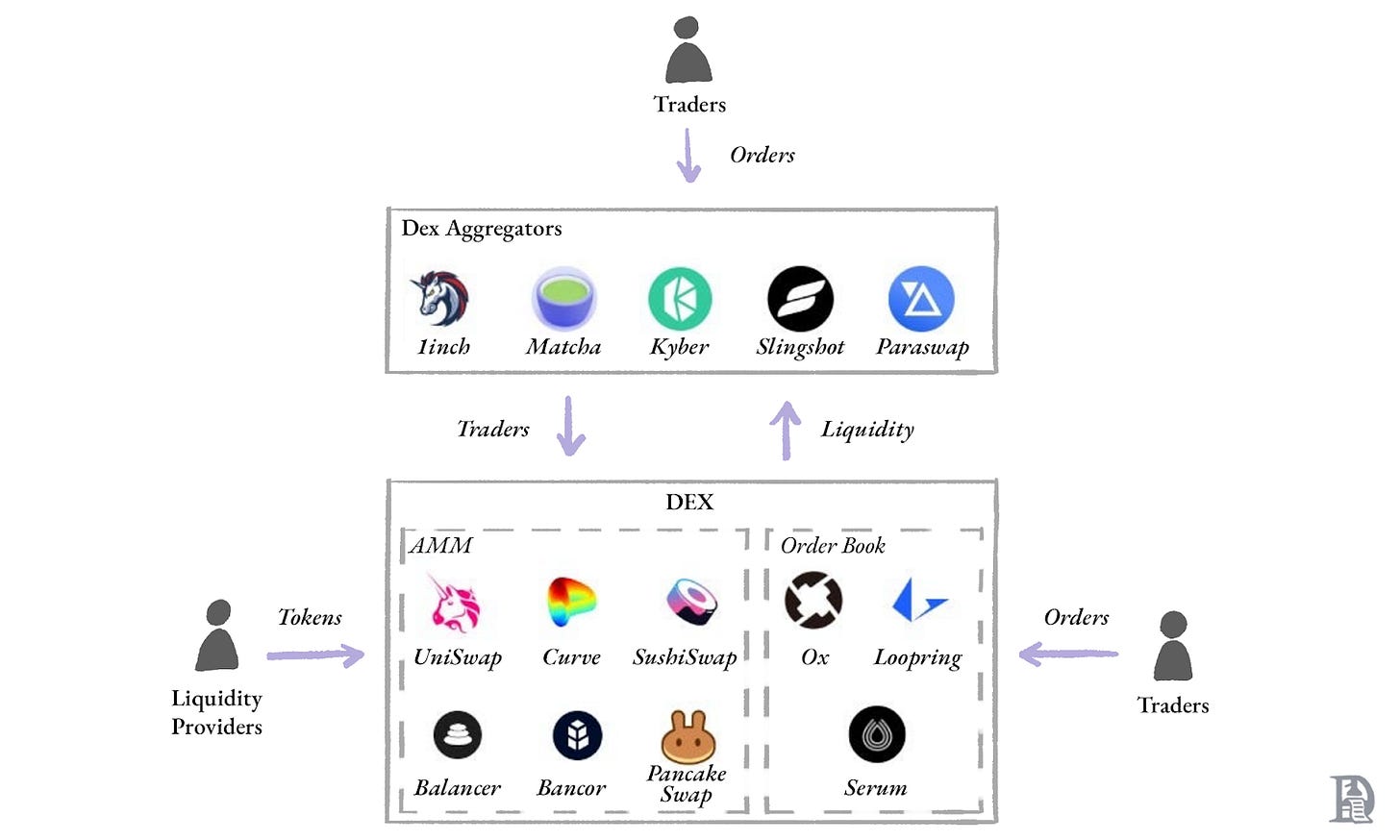

When execution fragmented across chains, the most immediate problem was navigation. Knowing where liquidity lived, which bridge supported a given asset, or which DEX offered the best price required manually checking multiple interfaces.

Aggregators addressed this by building backend infrastructure that indexed routes across bridges and DEXs and exposed them through a single integration surface. Instead of every application needing to maintain its own view of the ecosystem, they could rely on a shared routing layer to discover viable paths.

The pain point shifted from discoverability to coordination.

At that stage, aggregation seemed the best approach for orchestration and abstraction. It aligned well with how the system had evolved. Liquidity was already fragmented. Execution environments were already independent. Aggregators only needed to observe them and present options. The most obvious friction was informational, and aggregators solved that cleanly.

However, aggregation did not improve the user experience to the desired extent. Presenting information in a single interface did not mean that all user actions could be handled with a single click. In addition to worrying about execution costs, users also had to manage gas tokens across multiple chains. They had to undergo the ordeal of acquiring gas tokens on the destination chain to complete any cross-chain action.

Let’s say you had ETH and wanted to deploy USDC in some lending pool on Avalanche. Aggregators would swap your ETH to USDC, bridge to Avalanche, but could not deposit into the lending pool because you didn’t have AVAX (the gas token) on the destination chain.

Apps like Jumper solved the gas problem. Many routes now include refuelling or gasless execution. But this only fixes one visible dependency. Cross-chain journeys still lack end-to-end atomicity. Even with gas handled, the final protocol action can revert if the destination state changes while funds are in transit. The bridging is complete, but the intended outcome is not. Users end up holding the asset on the destination chain rather than completing the intended action.

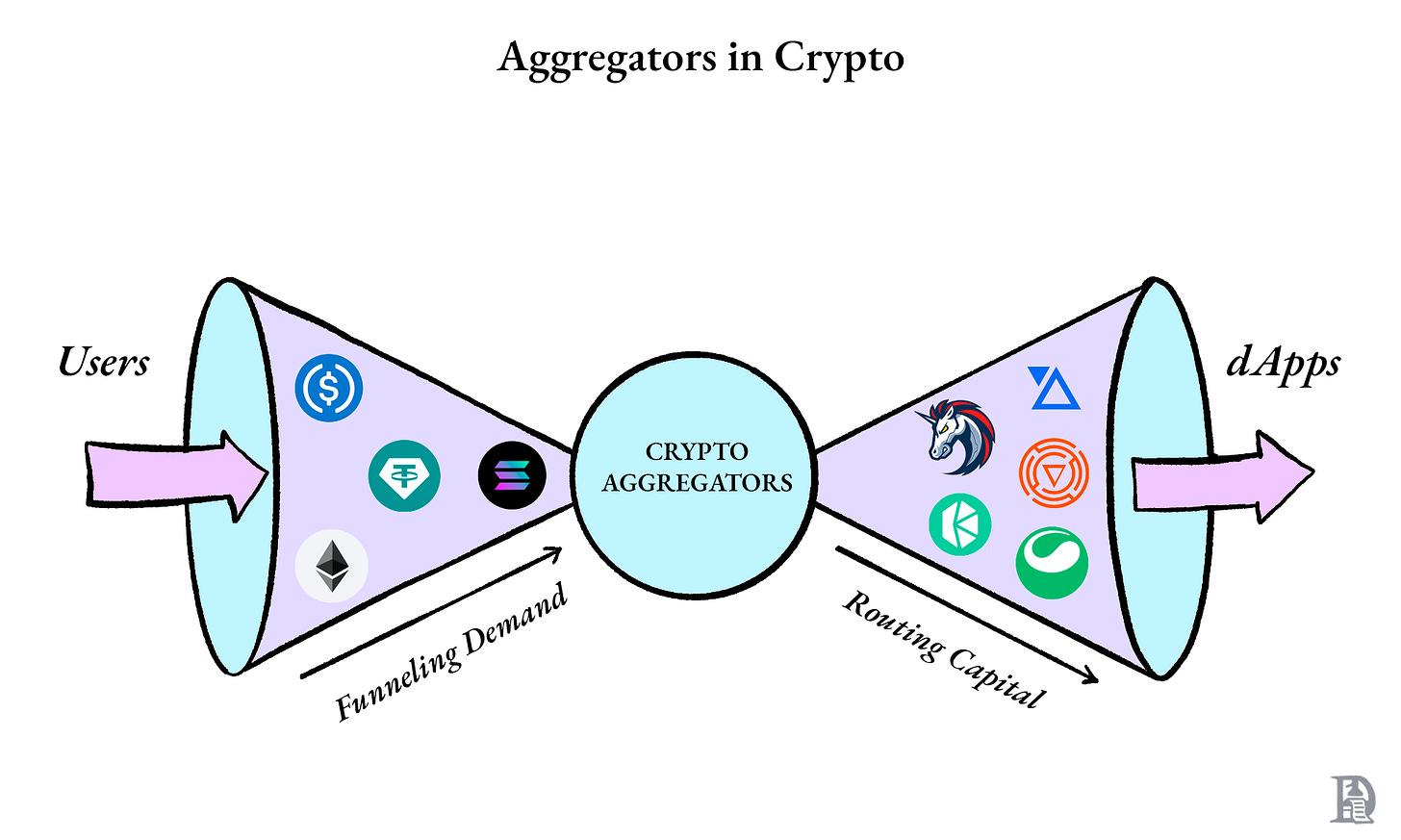

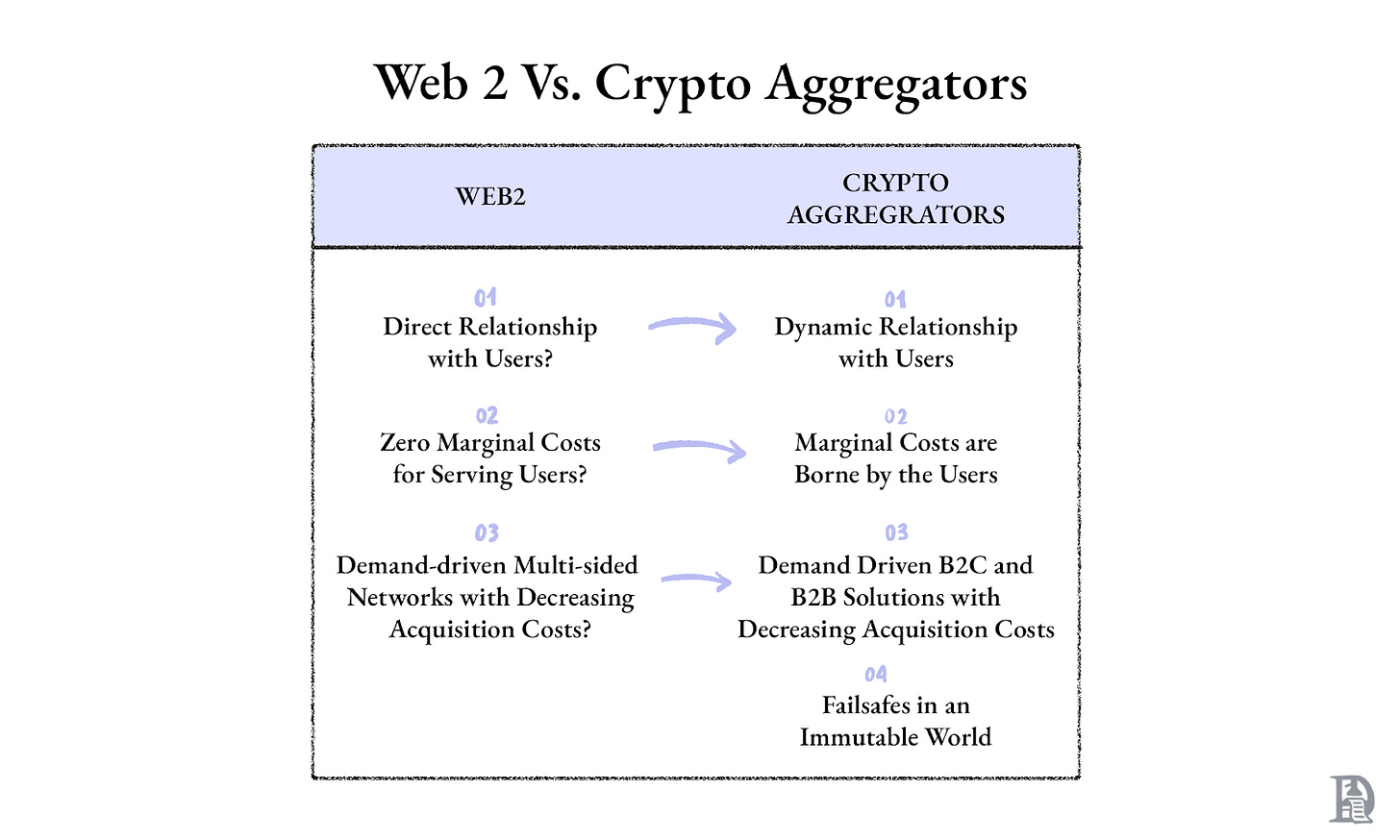

This limitation becomes clearer when compared to aggregation in Web2. According to Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory, aggregation works because the aggregator controls fulfilment. Marketplaces and platforms not only surface options, but also standardise how transactions are fulfilled. Even when supply is fragmented, execution remains predictable because the aggregator enforces it.

Crypto aggregation operates differently. Aggregators can suggest paths, but execution is carried out by independent protocols deployed across different chains. Increased usage doesn’t give the aggregator more control or improve reliability. It simply increases the number of times users are exposed to inconsistent execution outcomes.

This is why crypto aggregators do not produce strong demand-side lock-in. Users continue to switch based on incentives, price, and liquidity because aggregation alone does not guarantee the outcome users want.

Aggregation without a bias for action works up to a point. Once information is available everywhere, what users need is not more options but an infrastructure that can complete their desired actions.

From Transactions to Intents

Information is no longer the bottleneck. What matters now is how users’ choices become on-chain instructions.

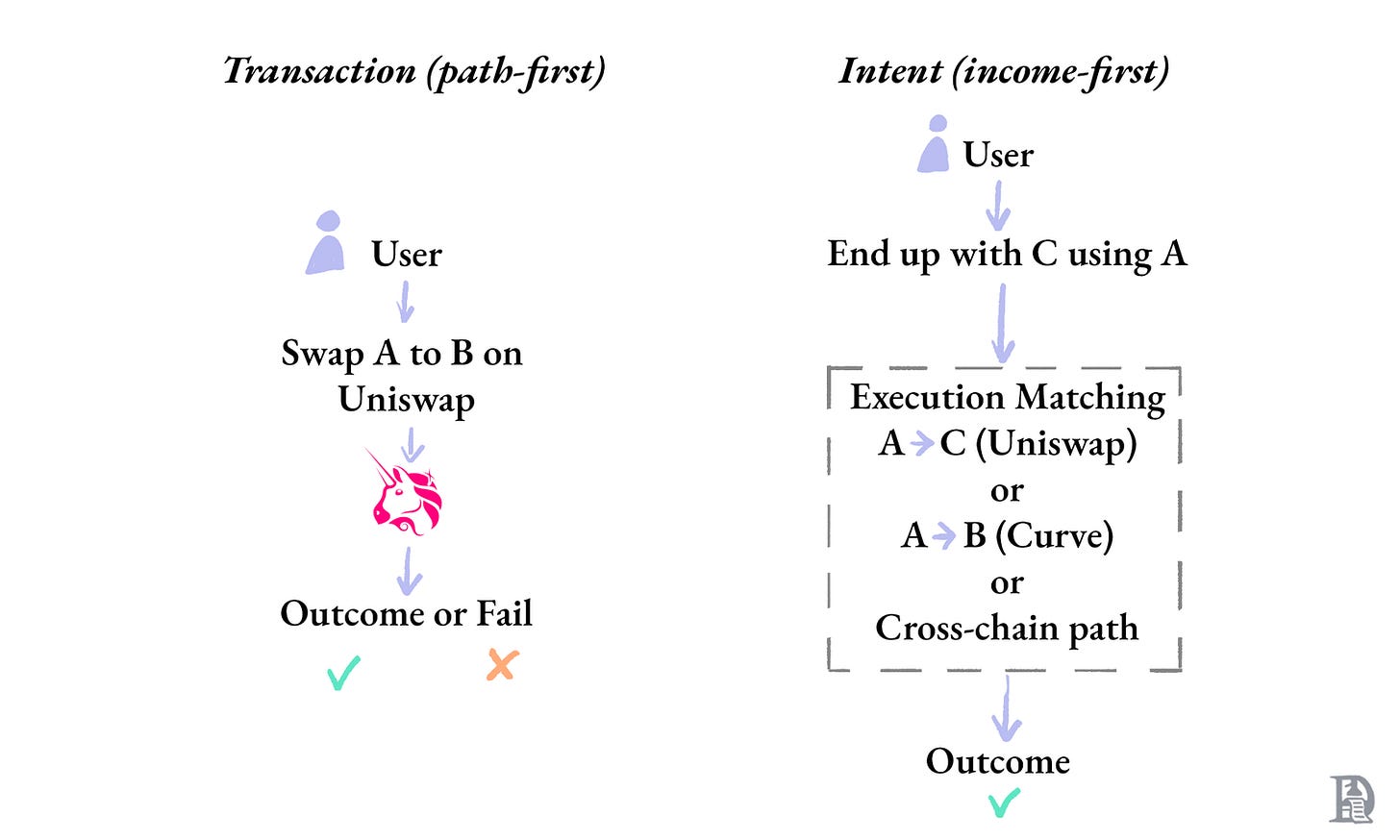

In practice, this means users submit a blockchain transaction.

A transaction specifies exactly which contracts to call, in what order, with what parameters and fee conditions. The network executes it as written or rejects it if any condition fails.

This is important because execution conditions on a blockchain are not static.

Liquidity changes from block to block as trades settle, pools rebalance, and gas prices move continuously based on network demand. Cross-chain transfers introduce additional delays that are beyond the control of any single chain. The transaction ordering can change at any time, depending on how sequencers or validators include transactions in a block.

In a multi-chain system, these factors vary not only over time but also across environments. If conditions change between submission and execution, as they often do, the transaction cannot adapt. It executes under the assumptions encoded at submission time, or it fails. The result is that either users face failed transactions or worse pricing. Neither is tolerable when they happen often.

The constraint is not that commitment exists, but when it happens. In a standard transaction, the user has to commit very early to a specific path. That path is fixed even before the system has access to the most current state.

Avoiding premature commitment requires a different kind of input. Instead of submitting an instruction that describes how execution should happen, the user submits a statement describing the outcome they want to achieve, along with the conditions under which that outcome is acceptable. The system is not told which contracts to call or which route to follow. It is told what must be true when execution completes.

For example, a user can instruct “acquire X amount of an asset within a given price range before a deadline” without specifying where liquidity should come from or which chain to use.

These instructions are called “intents”.

Pre-commitment still exists. A specific path must still be chosen before the transaction settles. The difference is when that choice is made. With intents, the path is determined closer to execution, using live information about liquidity, fees, and network conditions.

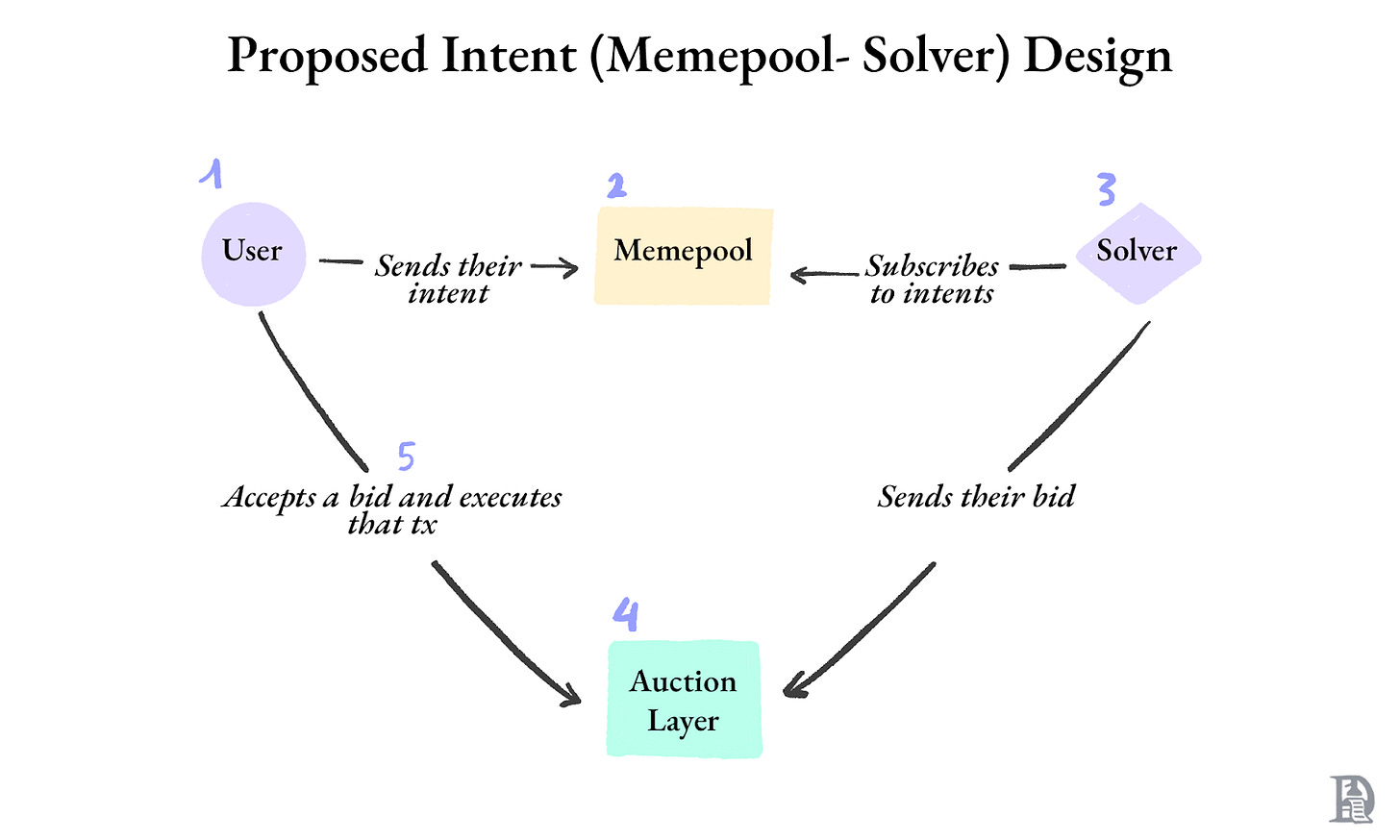

This separation between what the user wants and how execution occurs allows specialist actors, called solvers, to take over. When a user states an intent, they enter a shared execution environment where solvers observe it, simulate possible outcomes against live state, and compete to fulfil it under the specified constraints. The solver that delivers the best valid outcome earns a fee for the service.

What changes in an intent-based model is where most of the path-selection risk sits. Instead of users committing to a fixed set of steps upfront, solvers determine whether and how an intent can be completed under current conditions. If liquidity shifts or prices move, the solver must either adapt the path in real time or decline to fill the intent.

This reduces the user’s exposure to stale execution assumptions, but does not eliminate risk. Users still depend on competitive solvers and healthy market conditions. If there is no demand or liquidity for the desired asset, the intent may not be fulfilled.

Solvers compete only in markets where they can make a profit. When a user wants to participate in a market that’s not profitable for solvers, they may still be unable to sell the asset at the desired price.

Intents do not solve the coordination problem on their own. Solvers still need infrastructure that can reach liquidity across fragmented environments and adapt in real time. The open question is who builds the infrastructure that makes fulfilment dependable at scale.

Interoperable Markets

Early DeFi was built around the idea of “money legos”. Protocols were designed to be composable, meaning you could take an asset from one protocol, use it in another, and build increasingly complex financial products by stacking these primitives together. However, this only worked as long as everything lived on the same chain.

When execution spread across chains, composability broke. The building blocks still existed, but no longer snapped together. Every interaction now required assumptions about which chain, bridge, and pool would hold up under stress.

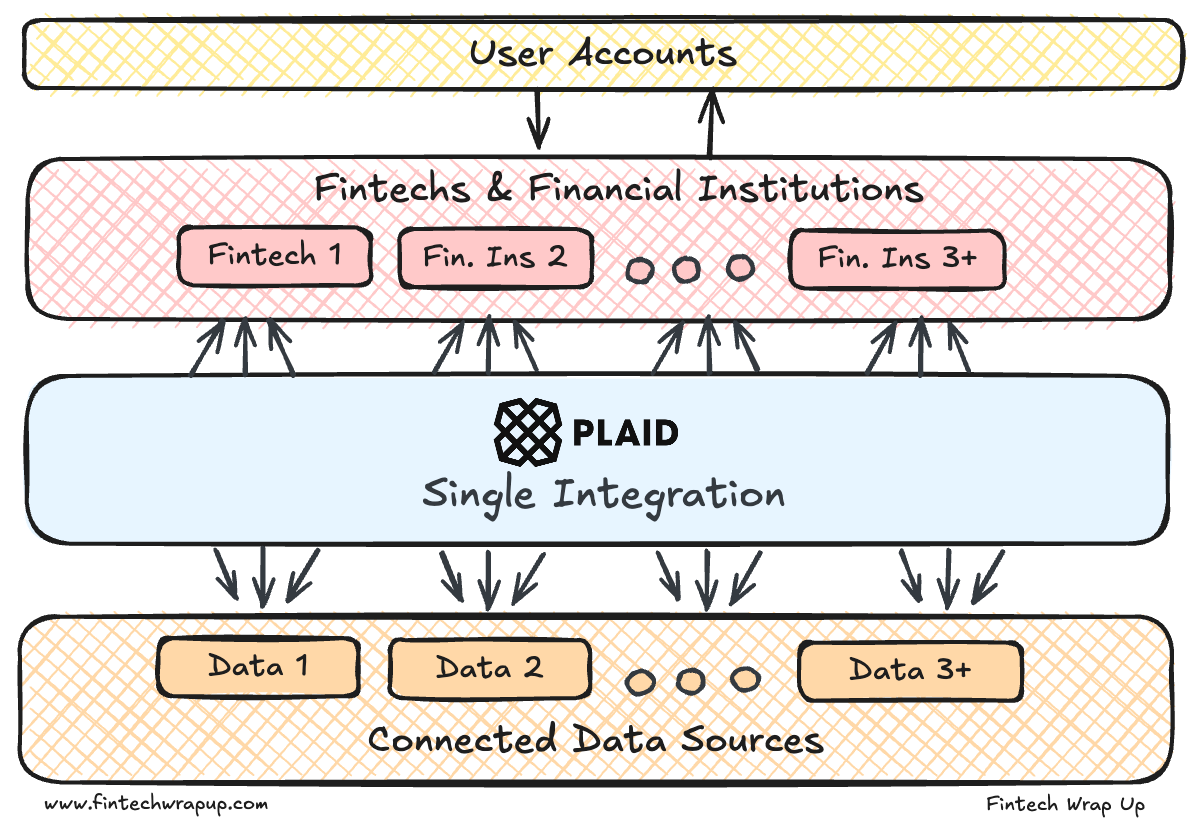

This kind of fragmentation is not unique to crypto. It’s similar to what Plaid solved for applications that wanted to read financial data across multiple banks.

Plaid created a common interface that allowed applications to read financial data regardless of where it resided. Developers could assume that balances and transaction history are accessible and focus on designing experiences rather than rebuilding plumbing.

Before LI.FI, liquidity technically existed across chains, but applications could not assume that access to it would be consistent. Every bridge, DEX, and chain exposes liquidity through its own interface, with its own limits. If an application wanted to move value across chains or compose multiple actions, it had to manage those differences. Building anything cross-chain meant stitching together bridges, swaps, gas handling, and fallback logic, and then hoping execution held up under real-world conditions.

LI.FI applies the same pattern to liquidity. It standardises how liquidity is accessed and executed across them. Applications no longer need to care where liquidity lives, which bridge supports which asset, or how execution should be sequenced. They can treat liquidity as something that can be reached programmatically and reliably, regardless of the underlying path.

The complexity now moves into the infrastructure layer, where it can be managed once rather than being rebuilt repeatedly. Instead of determining where liquidity lives, what matters now is who decides how it gets used.

At that point, the scarce resource is not liquidity itself, but rather order flow. In traditional finance, the two are largely interchangeable, but the subtle differences matter in crypto. Liquidity is passive. It sits in pools, vaults, and contracts. Order flow is active. It represents users and applications trying to swap, move, rebalance, or deploy capital. A pool with $10 million in USDC on a chain where nothing is happening has liquidity but no order flow.

What changes the equation is consistent, programmable access. When an orchestration layer reliably routes activity to the venues where execution is best, two things happen. First, market makers, solvers, and liquidity providers allocate to surfaces where order flow already concentrates and outcomes are reliable. Second, the system that controls the routing gains leverage. It can set expectations for execution quality, enforce latency and reliability requirements, and, over time, shape where liquidity is deployed.

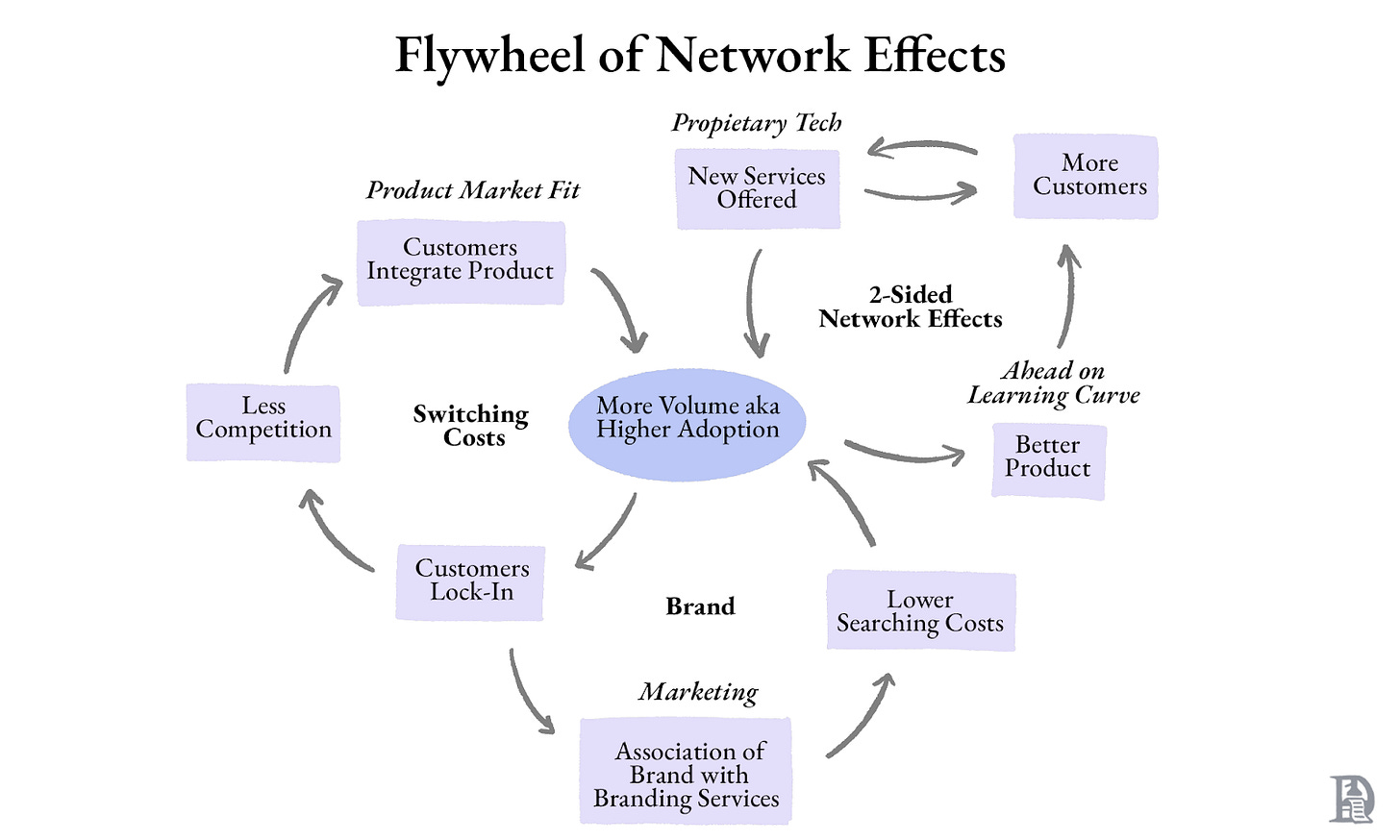

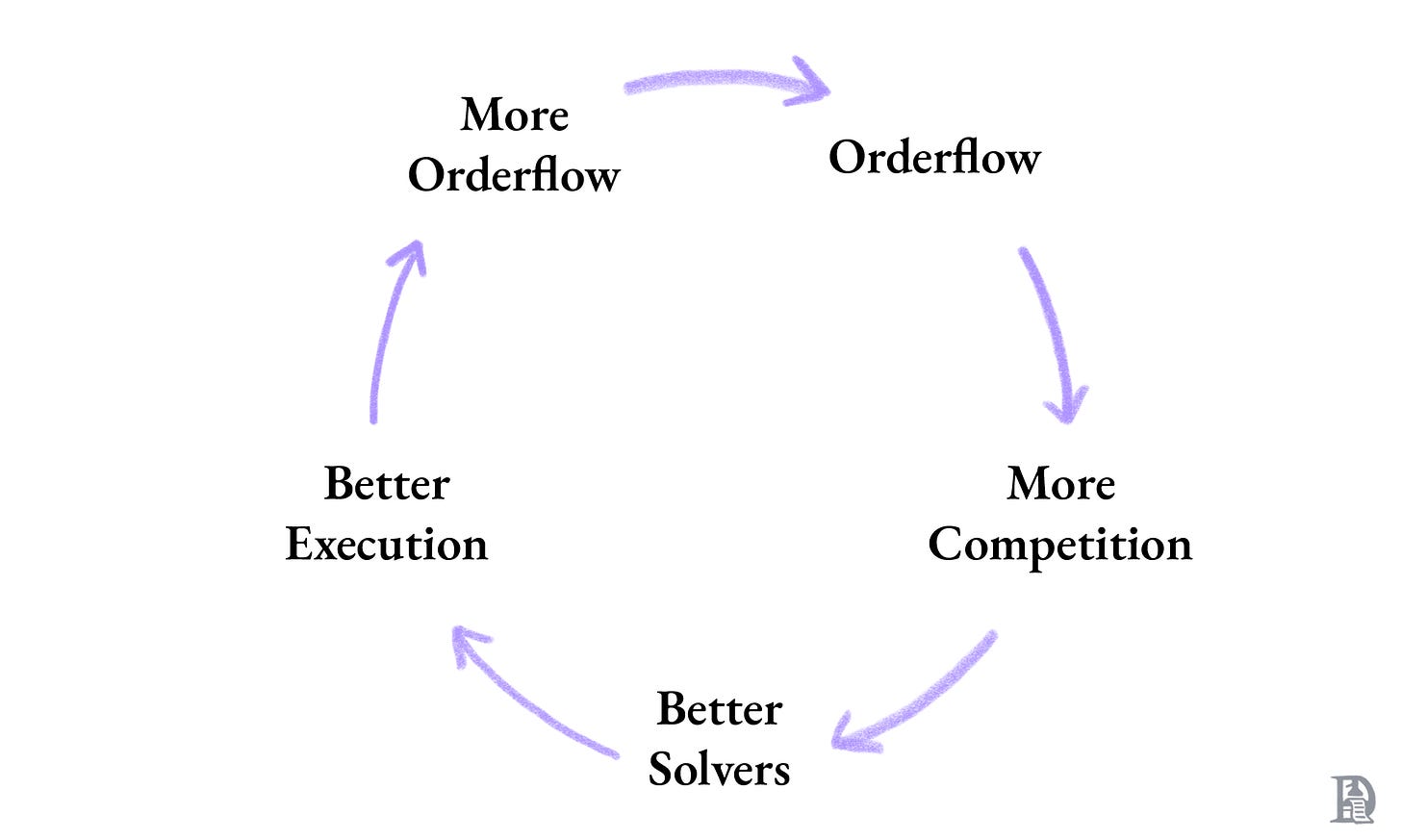

This is the flywheel LI.FI is building. More order flow attracts more competitive participants. More competition improves execution. Better execution attracts more integrations, which generates more order flow.

Interoperability concentrates order flow, and concentrated order flow becomes a marketplace.

When an interoperability layer aggregates meaningful order flow, it starts behaving like a marketplace by default. The job stops being “move tokens between chains” and becomes “take a user’s intent and reliably fulfil it under live conditions”. The user expectation has gone from “move tokens between chains” to “perform this action with these constraints”. In response, the interoperability layer must evolve as well. As a result, interoperability has order flow transitioning towards a marketplace.

Meta aggregation is a marketplace where intents serve as demand and solvers as supply. Multiple executors compete to fulfil each intent. The system picks the best option given constraints such as price, speed, reliability, and compliance.

Solvers that fail, misquote, or deliver poor outcomes lose flow, margin, and eventually relevance.

For solvers and liquidity providers, the value is predictable flow. Predictable flow lets them quote tighter, rebalance more efficiently, and run thinner margins. Unpredictable flow forces them to hold idle inventory, price wider, and avoid long-tail venues.

That supply and demand loop is also why marketplaces are hard to bootstrap. Nobody wants to supply early when demand is uncertain, and demand does not show up until outcomes are reliable. The typical solution is to proxy one side until the other has a reason to participate.

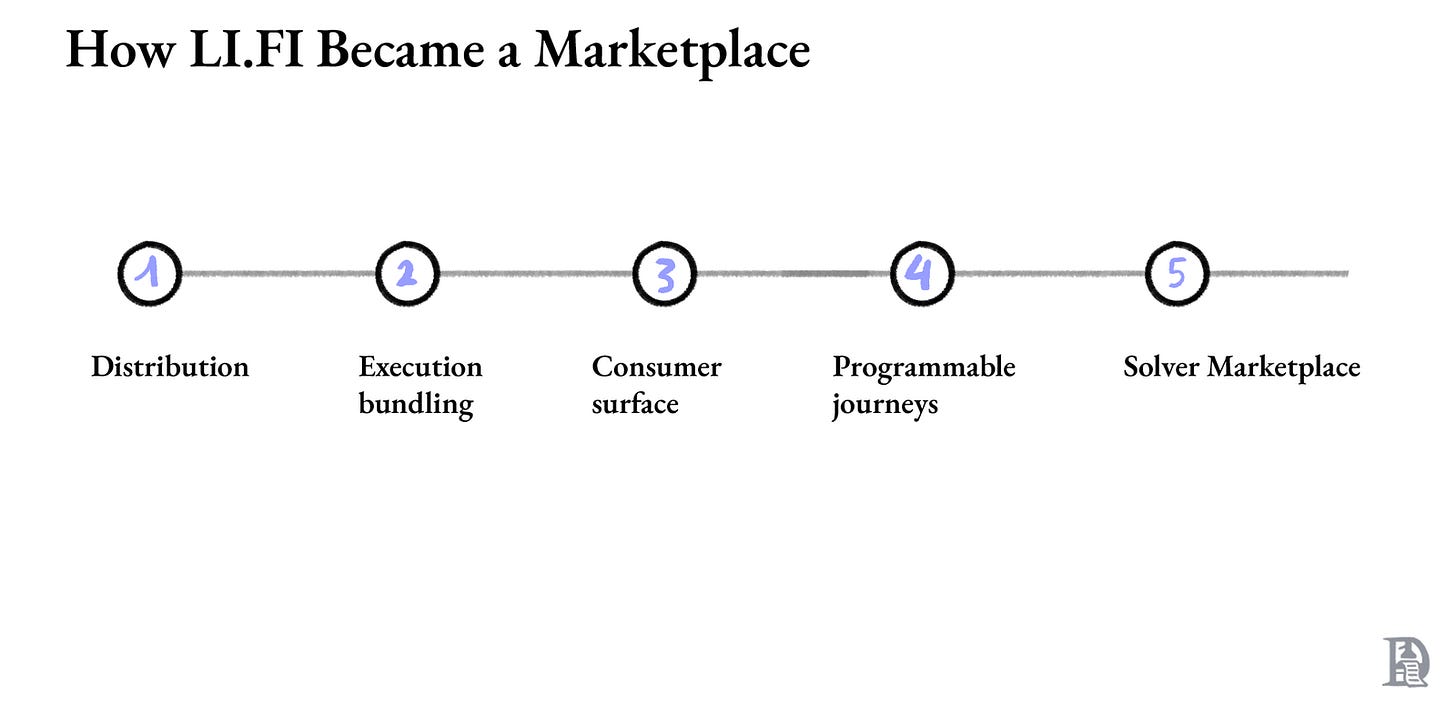

How LI.FI Became a Marketplace

LI.FI took a path that evolved into a marketplace. It started as distribution and execution aggregation.

The first move was embedding into production applications. Over 800 businesses now route through LI.FI. The demand side of the marketplace was seeded before the supply side existed.

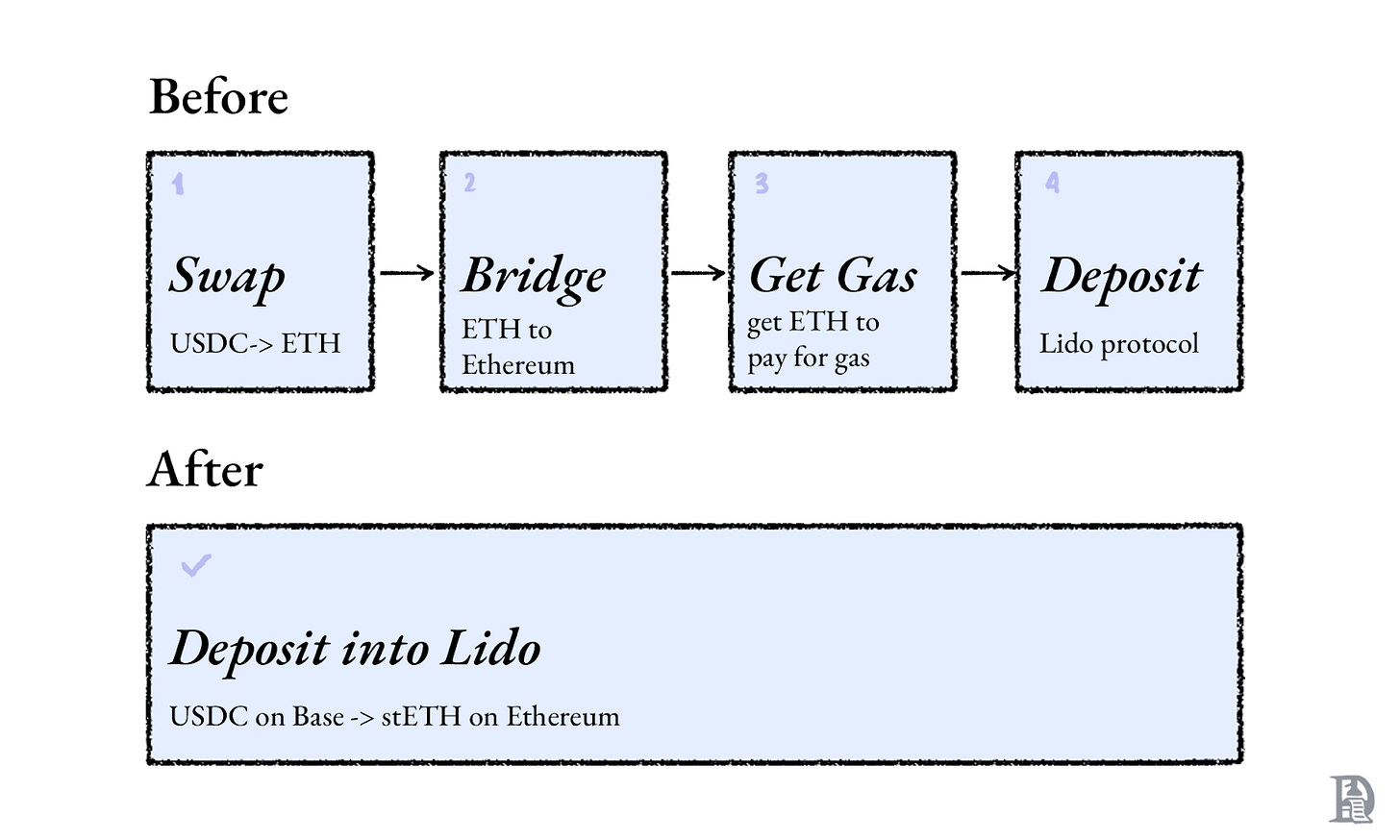

The second move was going beyond comparing prices to handling the actual execution. LI.FI deployed smart contracts across chains that could combine multiple steps into a single transaction for the user. Say you want to swap a token on Arbitrum, bridge it to Base, and swap it again into a different token there. Without LI.FI, that is three separate transactions you sign and monitor.

With LI.FI’s contracts in the middle, the user signs once. This entire process is non-custodial. LIFI doesn’t get to hold or direct users’ funds at any point. Funds move directly between smart contracts while remaining under user control at all times. The contract handles the swap, sends it through the bridge, picks it up on the other side, completes the final swap, and delivers the result.

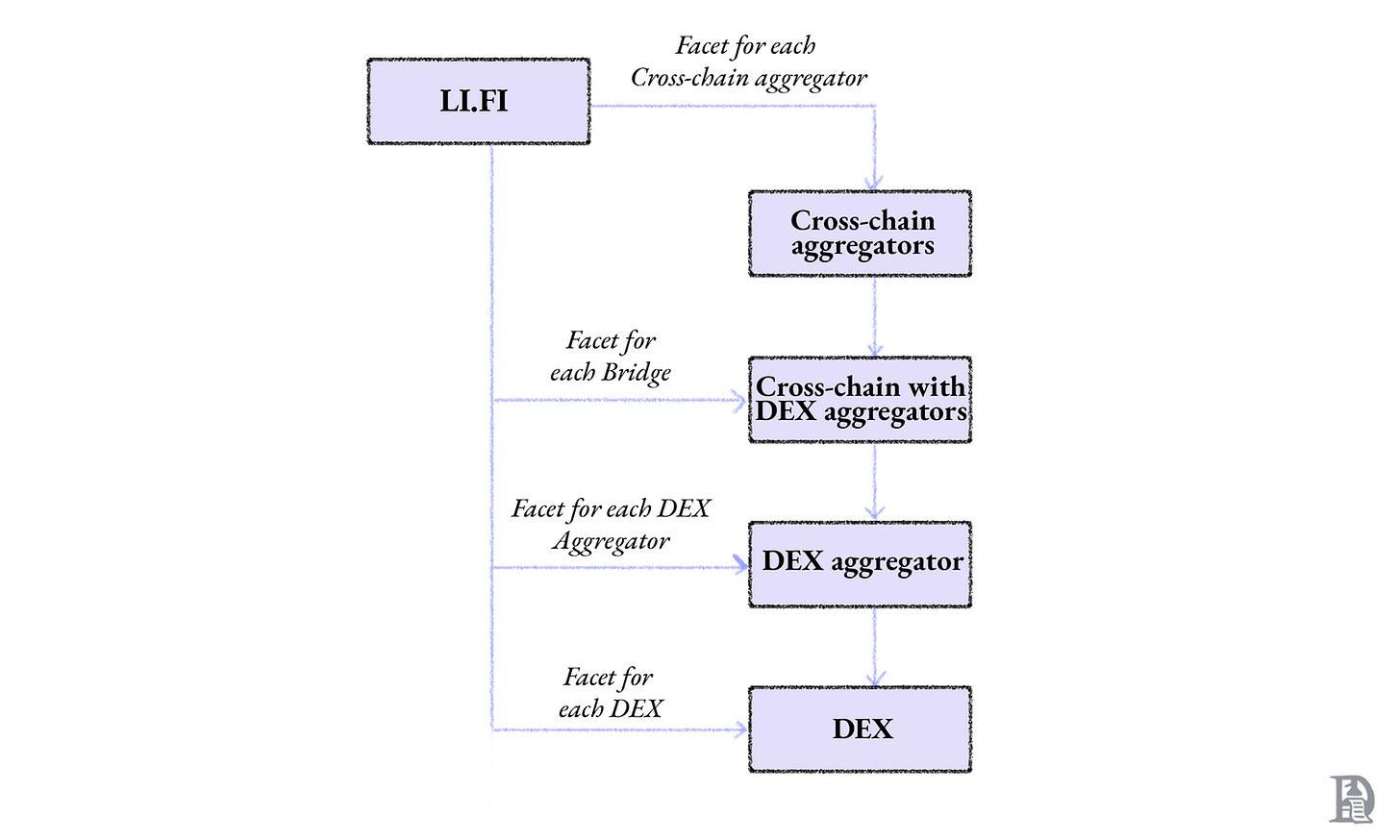

The system that makes this possible uses a modular architecture based on the Diamond Proxy pattern, also known as ERC-2535. Applications interact with a single entry point to the contract, which delegates actions to specialised modules based on what needs to happen. Each module handles one capability, such as a specific bridge, a DEX, an approval, or a protocol deposit. These capabilities can be added, replaced, or updated without redeploying the rest of the system.

As the cross-chain landscape is constantly evolving, this makes sense. New bridges launch, existing ones deprecate routes, DEX aggregators update interfaces, and protocols change their contract logic. A monolithic contract architecture accumulates technical debt with every change. Each new bridge integration or DEX update touches shared code paths, which means every modification carries the risk of breaking something that was already working.

Over time, engineering teams spend more effort maintaining existing integrations than building new ones. The Diamond Proxy pattern avoids this by keeping each integration isolated. When a bridge updates its interface, LI.FI updates one module. When a new chain launches, LI.FI deploys a new module to the entry point. The rest of the system is untouched.

For simpler integrations, LI.FI forwards generic contract calls with encoded data. For most major protocols, however, it maintains dedicated execution modules that interact directly with protocol interfaces. As of early 2026, LI.FI supports more than 80 such modules covering bridges, DEXs, and DeFi protocols. Each module is a well-defined execution primitive that integrators can combine in different ways.

This architecture also enabled LI.FI to offer redundancy at the infrastructure level. Some integrations intentionally overlap to ensure that if one path fails, another is available. Enterprise clients like Robinhood and Binance integrate LI.FI because they need consistent execution across every route, on every chain, with fallback mechanisms built in. The Diamond Proxy is what makes that possible without the contract system becoming unmanageable.

The practical result was that LI.FI could observe the full lifecycle of every transaction passing through its contracts. Where did failures happen? Which bridges were slow on which routes? Which DEX aggregators won on which chains? This data telemetry became a compounding advantage, one that competitors could only replicate by processing comparable volume through comparable infrastructure.

The third move was building a consumer surface. Jumper is LI.FI’s retail interface, where UX primitives ship fast and inform the B2B product. The clearest example is destination gas. Jumper’s Refuel feature lets users acquire native gas on the destination chain during the journey, eliminating the “funds arrived but I cannot do anything” failure mode. Once you stop failing at infrastructure, the question becomes whether the user achieved their intended outcome. Did the swap execute at a fair price? That is the problem worth optimising for.

The fourth move was making journeys programmable. Pure aggregation hits a scaling wall once users start expressing multi-step outcomes instead of simple “bridge and swap” requests. With a few chains, bespoke integrations are manageable. However, every new chain introduces new edge cases, every protocol has different smart contract interfaces, and composing actions across them manually does not scale. LI.FI spent two years building Composer to solve this.

Composer is a transaction orchestration primitive. It lets developers define multi-step, multi-chain DeFi workflows and execute them as a single transaction. The user signs once on their source chain. Everything else happens behind the scenes.

Under the hood, Composer compiles user journeys into executable blockchain instructions using a domain-specific language in TypeScript. A developer can write logic such as check the wallet balance, if it exceeds $1,000, swap into ETH, deposit the ETH as collateral into Aave, take out a 75% loan, and swap the proceeds into a stablecoin: multi-chain, multi-protocol, one transaction. The system uses dynamic call data injection to pass outputs from each step into the next, so there is no manual parameter handling between legs of the journey.

Critically, Composer includes its own transaction simulator. Before anything touches the blockchain, the full execution path is simulated to verify it will work. This is more than a nice-to-have feature. Failed transactions on complex multi-step journeys cost users gas and erode trust. Pre-execution simulation turns “hope it works” into “verified it will work”.

The practical result is visible in products like Jumper Earn, where users make one-click cross-chain vault deposits. Behind that single click, Composer is orchestrating a swap, a bridge, and a protocol deposit across different chains. It is also what LI.FI is rolling out with enterprise partners like Alipay, where the end user cares only about the outcome (yield) and not the six on-chain steps required to get there.

Composer matters because it expands what applications can express and execute with a single integration.

Before Composer, an intent was limited to “swap this” or “bridge that”. After Composer, an intent can describe an entire strategy. When you can express an outcome programmatically and simulate it cheaply, you can auction the right to fulfil it.

The fifth move was opening execution into an auction. LI.FI’s intent system is a modular auction layer where solvers compete to fulfil user intents. As mentioned earlier, the system is non-custodial. User funds remain in their wallets and move only via transactions they explicitly sign.

Every intent system faces a bootstrap problem: solvers won’t appear without order flow, and order flow needs solvers. In LI.FI’s case, years of aggregation had already built the demand side. Billions in monthly volume flowing through MetaMask, Phantom, Robinhood, and hundreds of partners meant solvers had an economic reason to participate from day one. The cold start problem was already solved before the product launched by proxying demand.

That is why acquiring Catalyst made strategic sense. The logic was to buy the best execution technology and pair it with the order flow moat that no intent-native competitor could replicate. Catalyst brought a flexible architecture supporting multiple transaction flows, settlement layers, and oracle options. LI.FI brought the distribution that makes solver economics work.

The intent system also changes what developers can build. A lending protocol cares about collateral thresholds and liquidation timing. A wallet cares about speed and simplicity. A payments app cares about predictable fees and settlement finality. Each has a different definition of “good execution”, and a generic intent format would be a terrible design choice to serve all of them.

LI.FI’s architecture lets each integrator define application-specific intents with their own constraints, routing preferences, and execution criteria, but all of this is resolved through the same solver marketplace. Developers get the expressiveness to build complex cross-chain flows through a single integration, without having to reason about the underlying execution paths themselves.

The result is an intent system that did not have to compromise on either side. LI.FI still aggregates other intent systems and does not lock applications into a single execution path. However, it now also operates its own solver marketplace, where the same order flow concentration that made aggregation defensible makes intent execution viable.

Google’s ad exchange followed a similar journey. Before programmatic advertising, advertisers negotiated with individual publishers. Google built an orchestration layer that aggregated both sides and introduced real-time bidding. The exchange became the marketplace for price discovery, its leverage stemming from concentrated order flow across fragmented supply.

The economics were similar, too. Advertisers did not want to integrate with thousands of publishers individually, nor did publishers want to integrate with advertisers. Both sides were okay with paying the exchange fees because the alternative was worse. The exchange captured value by reducing friction and allocating attention efficiently.

LI.FI sits in the same position. Applications do not want to integrate with dozens of bridges and DEXs individually. Execution providers do not want to build relationships with thousands of applications. Both sides accept routing through LI.FI because the alternative is worse.

Why apps keep outsourcing to LI.FI

A lending market, perp DEX, or wallet competes on liquidity, spreads, risk, and distribution. Interop reliability sits in the critical path, but it is still a cost centre. Owning the entire execution surface across chains, bridges, and protocols means running an integration business.

Many teams integrate with LI.FI because it lets them buy a single execution surface that already sits on top of many venues, learns from aggregate telemetry, and is moving towards outcome-based fulfilment via solver competition. As more apps route deposits and complex actions through the same layer, order flow concentrates further. That concentration is the moat. It improves solver economics, enhances routing quality, and deepens the marketplace.

The game-theoretical outcome is that one player concentrates order flow, and solvers have to compete for access to it. If they try to extract too much margin, someone else undercuts them. If they fail to execute, they lose allocation. The dominant order flow aggregator becomes the default price-setting venue.

Why Now?

When everything is growing, even mediocre infrastructure looks like it’s working. That’s what happened in the early days of crypto interop. But it’s changing now. The bar has moved from “does it connect chains” to “does the transaction actually go through every time”. Teams that aren’t specialised enough to win on performance or integrated enough to win on distribution are getting squeezed out. This consolidation is happening alongside three shifts that make orchestration infrastructure more necessary than ever.

1. Fragmentation is compounding.

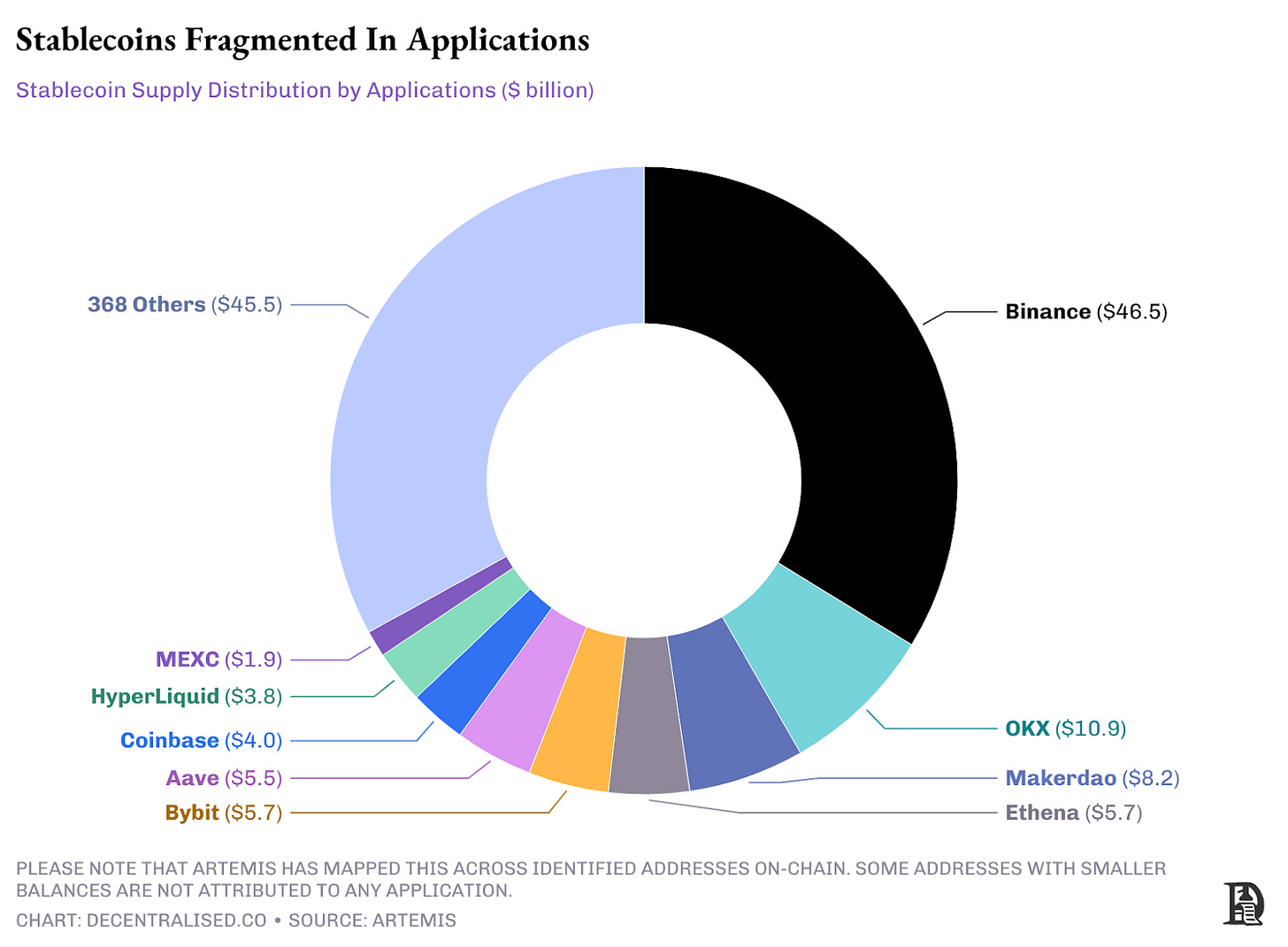

The early fragmentation problem was about chains. That problem still exists, but it is now joined by asset-level and rail-level fragmentation. Stablecoins illustrate this clearly because they are the single most used asset class in crypto, and the fragmentation runs through every layer. Stablecoins are fragmented at three levels – issuer, chain, and token standard.

Starting with the number of instruments, the stablecoin market now exceeds $300 billion in total supply, up from roughly $205 billion at the start of 2025. Although Tether and Circle control ~85% of the market share, there are more than 50 issuers with over $100 million in supply. These stablecoins are scattered throughout applications on multiple chains. The chart below shows the distribution of stablecoins across applications.

USDC is natively issued on 30 networks. USDT is supported on roughly 20 chains, and with USDT0 (its omnichain variant on LayerZero’s OFT standard), it reaches 18 more. DefiLlama tracks stablecoin activity across more than 100 chains.

Finally, there is the question of how the same stablecoin is represented. USDT exists as an ERC-20 token on Ethereum, a TRC-20 token on Tron, a BEP-20 token on BNB Chain, an SPL token on Solana, and so on. These are not interchangeable. You cannot send TRC-20 USDT to an ERC-20 wallet. Beyond chain-native standards, there is now a competing layer of cross-chain token standards designed to unify exactly this fragmentation.

LayerZero’s OFT (Omnichain Fungible Token) standard powers USDT0, USDe, PYUSD, and others. Wormhole offers NTT (Native Token Transfer). Chainlink has CCT (Cross-Chain Token). Axelar has ITS (Inter-chain Token Service). A newer standard, ERC-7802, allows tokens to expose structured metadata about their origin chain and verification endpoints. Each standard has its own set of stablecoin integrations, security assumptions, and developer ecosystem. The infrastructure designed to solve fragmentation is itself fragmenting.

The result is that a single dollar-pegged asset can exist as native USDT on Ethereum, native USDT on Tron, USDT0 via LayerZero’s OFT, wrapped USDT through various bridges, and bridged representations through A single dollar-pegged asset can simultaneously exist as native USDT on Ethereum, USDT0 via LayerZero, wrapped USDT through various bridges, and bridged representations through Wormhole or Chainlink. The same underlying dollar had different contracts, pools, and trust models. The coordination problem is now stablecoins × chains × token standards, and every combination creates a distinct execution surface.

As more real-world assets get tokenised, the same pattern compounds. A US Treasury bond might exist as an OFT on one chain, a native mint on another, and a CCT on a third. These differences determine how an asset is traded, bridged, and composed.

The execution surface is also splitting. Compliant rails with KYC’d liquidity pools are emerging for institutions. Privacy rails are emerging for those who need to keep the data confidential. Every new rail type is an additional execution surface that needs to be aggregated.

Companies are building their own chains to retain control over compliance, fee structures, and value accrual. Robinhood has its own chain. Stripe acquired Bridge and is building Tempo. Circle launched Arc. These are distribution-motivated chains built by companies with hundreds of millions of existing users, and every one of them creates new liquidity venues, new token representations, and new routing complexity.

If tokenisation follows the trajectory its proponents expect, every value chain that moves on-chain will introduce its own standards, its own chains, and its own fragmentation. The coordination problem will compound before it converges.

2. Regulation is accelerating asset issuance.

The GENIUS Act, now law, established the first comprehensive federal stablecoin framework in the United States. Although the regulatory clarity is good for adoption, the second-order effect is that it legitimised stablecoins as a product class and opened the door for a wave of new entrants.

This is not just a US phenomenon. MiCA is in force in Europe. Hong Kong passed its Stablecoin Ordinance in 2025. Each jurisdiction has its own compliance requirements, approved issuers, and preferred rails.

The GENIUS Act also prohibits stablecoin issuers from paying interest to holders. It does two things.

It drives the growth of crypto native stablecoins like USDe and USDH that are willing to pass on the yield to users.

It pushes yield-seeking innovation into adjacent instruments: tokenised treasuries and structured products that sit one layer above the stablecoin itself.

Each of these instruments needs its own token representation, its own chain deployments, and its own liquidity. Regulatory legitimacy accelerates issuance. Issuance accelerates fragmentation, and fragmentation accelerates the need for a coordinated infrastructure that can map, route, and execute across it all.

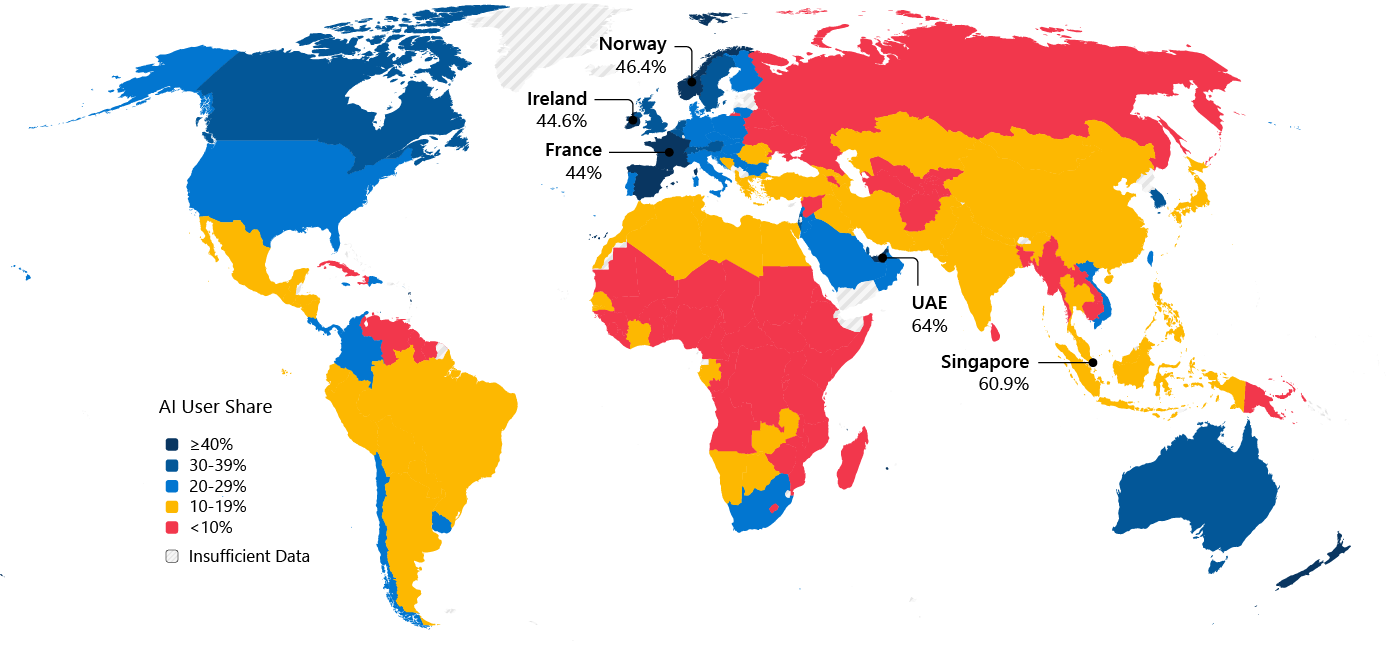

3. More and more executions are becoming autonomous.

As more AI-driven and agentic systems come online, execution increasingly occurs without a human in the loop. Agents rebalance portfolios, deploy capital, and move funds in accordance with predefined rules. There is no user selecting chains, bridges, or routes. There is only an intent and a requirement that it executes correctly under changing conditions.

According to Flashbots, autonomous execution is increasingly a first-order driver of how blockspace is consumed and how order flow is routed. Spam bots across rollups consume more than 50% of the blockspace while paying less than 10% fees. Meanwhile, private order flow accounted for over half of Ethereum gas usage. Bots on Ethereum accounted for more than 73% of DEX activity in August 2025, reinforcing the idea that execution quality and inclusion guarantees are increasingly determined upstream of the chain itself.

Agents do not encode chain-specific logic, bridge choices, or sequencing decisions. They express outcomes. They need something downstream to resolve their intent into an executable path, using live information about liquidity, fees, and network conditions. As the agentic economy grows, systems that can reliably execute without human intervention will matter more than interfaces.

The coordination problem is permanent. There will be no single chain; there will be hundreds, each with economic and technical reasons to exist. The infrastructure that maps standards, routes value, and coordinates execution across all of them becomes increasingly essential with every chain that launches.

What Could Undo This?

LI.FI’s thesis depends on fragmentation being a lasting feature of crypto, not a temporary phase.

The first is chain convergence. If activity consolidates onto one or two chains to the point where cross-chain movement becomes irrelevant, there is not much left to orchestrate. If everything that matters happens on Hyperliquid, you do not need a meta-aggregator. The counterargument is that if this were to happen, it would have by now. There have been stretches when one ecosystem dominated activity, but none in which the others disappeared. Cardano still exists. Every cycle produces new chains with real usage, real liquidity, and real reasons to exist.

The second scenario is standard convergence. Currently, the same asset can be represented across multiple cross-chain token standards, such as OFT, CCTP, NTT, and others. If one of these standards wins so completely that everything runs on the same rails, the mapping and routing complexity that LI.FI navigates gets much simpler. Today, at least three standards are prominent and growing independently. If a single standard captures enough adoption, the value of sitting between them shrinks.

Neither outcome looks likely in the near term, but they represent the structural conditions under which the LI.FI thesis would need to be revisited.

Where Interoperability Goes From Here

If the Internet pattern holds, raw transport is on the path to becoming a utility. Pure bridges are already headed in that direction. For a $1,000 cross-chain swap, most bridges and aggregators will land you at a similar execution price. The meaningful difference is whether the solution can navigate the maze of DEXs and bridges when some stop working, route around failures without the user noticing, and do so consistently across dozens of chains. Applications like wallets integrating cross-chain functionality natively are not necessarily optimising for the cheapest option, but for the one that does not break.

As this happens, bridges or DEXs will lose their identity. They fade into the background, as physical network infrastructure did once the Internet standardised its transport layer. Users and applications will stop thinking about which bridge moves their assets. They will care about whether assets arrive, and at what cost. In this world, the value migrates up the stack, away from the pipes and towards whoever coordinates the journey between what a user wants and where liquidity actually sits.

The solver networks that attract the most order flow will attract the best solvers. The best solvers will deliver better execution. Better execution will attract more order flow. The flywheel is already observable. Only consistent demand makes this durable, though. Orchestration solutions are in a unique position as they sit close to where the demand originates.

Bridges and liquidity venues hold supply; orchestration layers control demand routing. As order flow concentrates through these layers, suppliers compete for access to the demand surface rather than the other way around. Greater competition means their margins compress. Their negotiating leverage diminishes. The value accrues to whoever sits between user intent and liquidity deployment.

Then the cycle restarts at a higher layer of abstraction.

When execution infrastructure is reliable enough that applications stop worrying about whether cross-chain transactions land, they start worrying about how those transactions land.

A payments company needs predictable fees and settlement times. A regulated exchange needs KYB-verified execution partners. An AI agent rebalancing a portfolio needs reliability guarantees that differ from those required by a human clicking “swap.” Alipay does not care about the composable transaction steps underneath. They care about one-click yield. A company tokenising US Treasuries needs solvers with permissioned access to mint and burn those specific tokens, not a generic solver pool.

This is the fragmentation that comes after connectivity is solved. First, bridges enabled the movement of assets across chains. Then, token standards from the likes of LayerZero, Chainlink, and Circle made interoperability more structured. At the application layer, users’ needs diverge faster than any generalised system can accommodate. Infrastructure that forces uniformity loses to infrastructure that enables specificity. The teams that win will be the ones letting applications define their own constraints, solver selection, oracle preferences, compliance filters, and execution timing, without having to rebuild the stack from scratch.

There is no single end state here. We will be tokenising different assets using different standards across different chains for the foreseeable future. The coordination problem will compound before it converges.

LI.FI’s bet is that the on-chain world is headed towards a landscape of millions of tokens, hundreds of standards, hundreds of chains that matter, and application-specific intents that a one-size-fits-all execution cannot serve. In that world, the durable advantage belongs to whoever has the deepest integration footprint into the surfaces where intent originates, the solver depth to execute across the widest range of conditions, and the flexibility to let each application define what “good execution” means for its users.

Strowger did not build a better telephone operator. He made the operator unnecessary by letting the caller’s intent route itself. The bridges, DEXs, and liquidity venues are the operators. LI.FI is building the switch.

Streaming the T20 World Cup,

Saurabh Deshpande

Disclosure: This piece was part of a sponsored collaboration. Authors or DCo may own assets mentioned in the article.