The Creator Economy In Gaming

Fun and profit from constrained randomness.

Hello!

Today we are going to look at gaming. For several reasons, this is one of the few consumer-facing use cases with a real shot at scaling to a billion users in the digital asset ecosystem. Firstly, gamers are already accustomed to digital assets; they regularly pay for in-game transactions (i.e., pixels). Secondly, this is a high-transaction frequency use case in which our present-day financial infrastructure fails to serve the global market well. Finally, gaming delivers the key function of providing meaningful distraction and community at a time when we are devoid of both.

Today’s piece is co-authored with Siddharth Jain - a VC and gamer who has seen the inner workings of guilds and gaming studios over the past two years. Siddharth set up IndiGG in 2021 and has been an active advisor to several gaming companies that are household names in the Indian market. He enjoys playing Dota & Zelda anytime he finds some spare time, so I know he’s serious about this gaming thing.

Over the past few weeks, we have discussed how Web3 infrastructure can elevate user-generated content (UGC). We are publishing this piece as our thesis on how blockchains and gaming intersect in the next few years.

Costly JPEGs & Non-existent Users

The funding for blockchain-related games surged from $83 million in 2020 to over $2.4 billion in 2021. The success of Axie Infinity fueled this 30x surge at the dawn of a new category. The amount of funding that went into the ecosystem is likely much higher as founders and VCs rushed to build everything from developer tools to wallets for the gaming ecosystem.

Yet, two years later not much to show for the hype.

(Yes, we know it takes years to build AAA titles like Fortnite from the ground up)

There are various reasons for this. For one, gamers traditionally have played for fun and distraction. Currently, Web3 gaming is too focused on the financial aspects to compensate for the lack of an excellent in-game experience. You cannot create a Web3-native version of GTA 5 or Red Dead Redemption in 18 months! And for studios with an existing user base, force-fitting on-chain primitives made no sense. Their users were vocally opposing these ideas, thus creating the potential for chaos and bad PR. Pundits in the industry even argued in-game assets were burning down the planet at one point.

On the flip side, the bear market hit Web3-native games like Axie Infinity, which saw a surge of new users in Q3 2021. Declining token prices meant reduced financial incentives for the average user to care about Web3-related games. The consumer began seeing these products as more transactional and less fun. These games couldn’t sustain as avenues for making a living or an excellent outlet to kill time. The games saw a rapid reduction in their daily average users and revenue.

Established gaming studios with decades of experience building games did no better with their Web3 projects. Ubisoft barely made $400 by integrating NFTs into Ghost Recon, one of their flagship games. The response was so bad that they stopped shipping any NFT-related updates in less than five months.

The reason is simple: When we force Web3 as a narrative on gaming, we take a product that already works and adds layers of complexity to it. Users will only bother if an exponential advantage is offered. Over the years, gamers saw studios develop more and more ways to extract money from them.

In their current form, NFTs are just another way for publishers to fleece their users. There used to be a time when gamers could trade physical copies of the games they loved with friends. That vanished when game distribution turned digital, and platforms like Steam and Origin became centralised marketplaces for games.

Game developers realised that instead of releasing a complete game, they could sell extensions for basic games in downloadable content (DLC). When publishers lusted after even more profit, micro-transactions were introduced. And the most debatable monetising practice in gaming over the last decade was likely loot boxes, effectively lottery tickets sold to minors who hoped to get a random upgrade for their in-game characters.

Consider watching the video below for an extensive breakdown of how gamers perceive gaming studios monetising every moment they spend in a game.

The past 15 years have seen both success and controversy around game monetisation. It used to be that you could buy a game and hope to own it completely without small transactions or extension packs. But the unit economics for game publishers don’t work out well, especially if it’s a multiplayer game. There are ongoing expenses in maintaining servers, moderating users, releasing features, and building machinery that keeps the game relevant.

If all those expenses were bundled into one, the game would die due to few users being able to afford the game. This is partly why new-age games like Fortnite have transitioned to a subscription model. In addition, ecosystems like Microsoft’s Xbox and Sony’s PlayStation have their own bundled platform subscription packages.

The way to think of game platforms is as digital townships where users gather, interact, play, and often transact. Unlike the early 2000s when games were linear experiences where you played through a storyline, these digital products are now social-consumption goods packaged as game experiences.

The reason why we face backlash every time a new financial primitive is introduced in gaming is that it empowers developers over users. Think of visiting a restaurant that requires you to pay each time you take a bite of a dish you eat. This is what tools like microtransactions are in their current form. Especially in Web3-native games where the “entry requirement” is generally buying a jpeg for what could be a month’s wage.

For equitable outcomes for both gamers and developers maintaining these digital realms, we need to look towards financial primitives that serve both parties. Games are already seen as “homes” by those who spend the most time with them. And yet, very few primitives give creators and gamers ownership or the means to profit directly from their work in games.

It may seem far-fetched to think there will be a market for creators making a living off in-game experiences. And many could remind us that most gaming enthusiasts spend their time managing communities for non-transactional benefits like the relationships they build.

But this is akin to suggesting Substack can’t be a thing because Wikipedia exists. Web3 games today focus on the levers of better financial infrastructure and asset verification. If these primitives are to be relevant, we must look at empowering users and creators through this infrastructure. That is where UGC comes in.

Understanding User-Generated Content

Most traditional publishing houses have a limited rate of production. This is by design, as high-quality content creation is time-consuming, whether writing books or producing movies. It takes time to seek inspiration and the motivation to translate thought into consumable content. When the content is finally produced, there is the added risk that it may appeal only to a small subset of users globally.

It’s why most big movies focus on universally relatable emotions such as love and the heartbreak that inevitably follows it or the hero arc of a protagonist rising from nothing. They optimise for relatability to the masses. Study any traditional print or cable-based publisher, and you will see that their audience usually has shared ideological leanings.

The internet disrupted this relationship quite a bit. Instead of a centralised publishing house making content, everybody is creating and consuming content. As the internet dramatically reduced distribution costs, it made sense to pass on the “costly” aspects of creating content to users eager to build an audience.

Unlike traditional media outlets, the cost of creating content diminished to zero for social networks while simultaneously making it possible to capture an ever-increasing amount of user attention. Stick in an ad here and there between all that time spent on your platform, and you have a money printer in the making!

These dual levers of passing on the cost of producing content to users while increasing the amount of time the average user spends on these platforms are at the crux of what makes new-age social networks so profitable. They acquire user attention with minimal operational costs compared to traditional media outlets. When you spend time scrolling through TikTok, ByteDance (the company behind the app) is not spending any added resources creating an endless content feed.

Their cost is confined to content moderation and maintaining the servers. For a sense of scale, consider that Facebook spends over $500 million for Accenture to help with moderating content. By some estimates, some 15k-30k moderators sift through content on the social network on any given day.

In the context of gaming, UGC took off on the web through streams of watching other gamers play. It may seem strange if you are not a gamer, but gamers often enjoy watching others play. Especially if there is a funny commentary to go with it! Modest Pelican and Girlfriend Reviews are two of my favourite gaming reviewers if you want to see what these generally look like.

Twitch is the de facto streaming platform for gaming-related content today. All viewers combined spend 2,500 years watching Twitch content every year.

But watching others can be fun only for so long. So some games allow creators to build and sell assets to others. This ranges from developing a simple racing game to a game that requires a complex strategy to win. Suddenly, the things a player can do are not limited to what the developers offer. Instead, users can create infinite variations of different games on top of it.

Think of it as the difference between releasing a book and releasing a copy of Microsoft Word and seeing what unique stories your creators come up with. The game studio owns the IP rights around the characters and the code behind the world that gamers play in. They are also responsible for bootstrapping the initial user base around the game.

Games like Counter-Strike and Age of Empires allow gamers to create unique levels and challenges within the game. Fortnite has a creative mode that enables users to build worlds and characters of their own. Far Cry 5’s arcade mode consists of custom game levels created by community members. Unlike mods, UGC in games generally requires lower expertise and is often supported by the game’s design mechanism. Users have been discussing them since as early as 2012.

From Games To Platforms

UGC is a powerful lever for new games and serves two core functions. Firstly, they extend the time a userbase can be engaged with a game. Linear games with progressive storylines are interesting until the story is played out, after which gamers don’t have much reason to continue gaming. Online modes, such as the ones offered by GTA 5, extend the longevity and profitability of a game. This is why GTA 5 by Rockstar is the most profitable entertainment product of all time. It has done north of $6 billion in sales worldwide.

Secondly, it allows the most active contributors to the game to stay invested. Building unique levels and worlds within a digital realm creates an emotional attachment to the game. The feedback gamers receive from other players serves as validation for their effort as games turn to outlets for creative expression. In essence, UGC helps a portion of a game’s user base go from passive participants to active creators.

Most games tread a proven path of launching with an engaging storyline (e.g., Assassins creed or Call of Duty) and eventually transition to outlets where UGC is a subsection of the broader content offering. More recently, games like Fortnite have shown a model where users are engaged less by battle royales and more by active, chaotic, and random participation by a large subgroup of online users engaging with custom content.

The randomness that comes with large multiplayer games becomes the hook that attracts users, as the gameplay is unpredictable. Every gaming session has something different to offer. This powers a potent feedback loop where users are incentivised to use the product simply because they don’t know what to expect.

Minecraft and Roblox are the exceptions to this norm; they have transcended to being platforms. A game that has become a platform usually has relatively little IP and can have fluid storylines depending on who is building on it. These are games where users spend more time on user-generated gaming experiences than storylines or levels developed by the studio behind the game. Fortnite is in a unique period of transition to being a platform. According to reports, roughly half of the user’s time in the game is now spent interacting with UGCs.

Transitioning to being a platform over time is the holy grail for most games and opens pathways to monetise in unique ways. Fortnite, for instance, has collaborated with over 100 brands over the past few years. In addition, focusing on being a UGC platform allows games to pass on some revenue from users to creators.

In 2021, Roblox had over 1.7 million unique users creating content on the platform. Of these, over 8,600 earned over $1,000. In addition, some 74 developers net over a million dollars each. It is not just about the money, though. It is about variety and the number of human attention games that have transitioned to being platforms that could attract. The median user on Roblox visited 40 different experiences on Roblox in 2021.

In the same year, the game had over 1,900 experiences that generated at least one million hours of engagement in a given year. Over 350 experiences generated ten million hours of engagement or more. Half of all adult Roblox users are transacting users, with one in ten doing transactions over $100 each.

They have gone from stand-alone media consumption goods (like TV shows) to platforms where users create the bulk of the experience a user would have.

Challenges with User-generated Content

UGC is a powerful lever for games looking to evolve into transactional platforms. But it may not always function as intended. Even large gaming marketplaces like Steam have struggled to maintain creator pay-outs long enough. In 2015, long before NFTs or royalties were a thing, Steam had a creator workshop segment that paid out over $50 million in fees to creators building mods, skins and the like for a handful of games.

This was when only 25% of the royalties were paid out to creators. The programme had to be shut down after four months, citing “unexpected user behaviour.”

Roblox and Fortnite are powerful platforms creating entirely new forms of work. A decade or two back, passionate gamers had few avenues to translate their time and skill into revenue. Today the average developer earns about 0.29 for every dollar spent on Roblox. If that seems low, consider that Fortnite creators only make about 5% of the revenue they generate for the platform.

It is not so much so that the gaming studios behind these pieces are stealing from the creators. There are expenses in maintaining the game, paying for ongoing development and platform fees from Xbox, Apple, or Google. In most instances, users are happy to see any money coming from their efforts. The annoyance, from their perspective, comes from the threshold limits required for a payout. Fortnite, for instance, requires a $100 minimum due to financial transaction costs. Embedding Web3-native wallets and using tools like Stripe to make pay-outs in USDC could reduce the payment threshold to a fraction of what it is today.

A different part of the equation is the mechanisms through which copyrights are enforced today. It becomes hard to verify automatically and vet which user created an experience first. Manual intervention helps but may take weeks. Then there’s the risk of infringing copyrights through music or art in a game.

Recently, Roblox paid a $200 million settlement fee for music copyright infringement. They have since collaborated with several large studios to allow the embedding of known tracks in experiences without violation.

You may wonder why we care so much about copyrights and payments in a strange game. It is because these virtual worlds are workplaces for creators in the future. In 2021 alone, Roblox paid over half a billion to creators on the platform. Far from the $1.6 billion OnlyFans paid creators on their platform in the same year. But it shows that developing, nurturing, and maintaining gaming experiences could be a form of employment in the future.

If that is the case, then payment rails and copyright management must be done through better tools that don’t require human intervention. And ironically, many of the primitives we talk about in the blockchain ecosystem today fit here perfectly well.

Hyper-financialisation of Gaming

A few weeks back, I asked Siddharth Menon from Tegro, which is the most “fun” game in Web3. He responded that users don’t come to Web3 gaming for fun alone. Half the entertainment is in the financial aspects of these communities.

“To me, game mechanics for fun is a solved problem. It's not new, and it has evolved over many years. However, web3 games offer a new problem. A layer of an open economy with balanced financial incentives and a game that solves both is a winner. The game needs to be designed not just for players but also for investors & traders – Siddharth Menon

This is why Web3 gaming is controversial when traditional gamers look at the industry. The industry is built for speculators rather than gamers today.

The reason for this ties back to what I initially said in the aggregation theory and Web3 piece. It makes user attribution and payment verification far more straightforward than it would have been in traditional infrastructure. For example, say you had to pay $100 to a thousand users as a Delaware LLC.

The process of onboarding users, collecting their banking information, taking care of necessary AML/KYC checks, and processing payments is a liability on your books. If it were done through stablecoins, on-chain, the liability would be disintermediated by external parties (such as exchanges), each subject to strong regulations.

This matters especially in UGC because suddenly, you have opened the gateways for two things. On the one hand, as a platform, you can reward users that contribute proactively in the early stages via in-game assets. On the other hand, you can bootstrap a marketplace for these assets where users can liquidate their hard-earned in-game assets.

These economies would not require studios to burn capital to incentivise creators. Amy Wu explained this phenomenon quite elegantly in a recent conversation.

The content treadmill is one of the biggest challenges in sustaining a great game. UGCs, combined with token incentives and liquid markets, are powerful levers for onboarding a generation of creators that would have otherwise not bothered with Web3 gaming at all. Advances in both generative content and experimenting with creator incentives including tokens are early and promising. -Amy Wu

What would (ideally) happen is that users who have spent their time either playing the game or creating in-game experiences would trade the assets they received with users that don’t have the time or skill to play games for hours to acquire these assets. I was sceptical about this thesis, so we reached out to Roby John from Super Gaming (one of India’s largest gaming studios) to vet this thesis. And this is what he had to say.

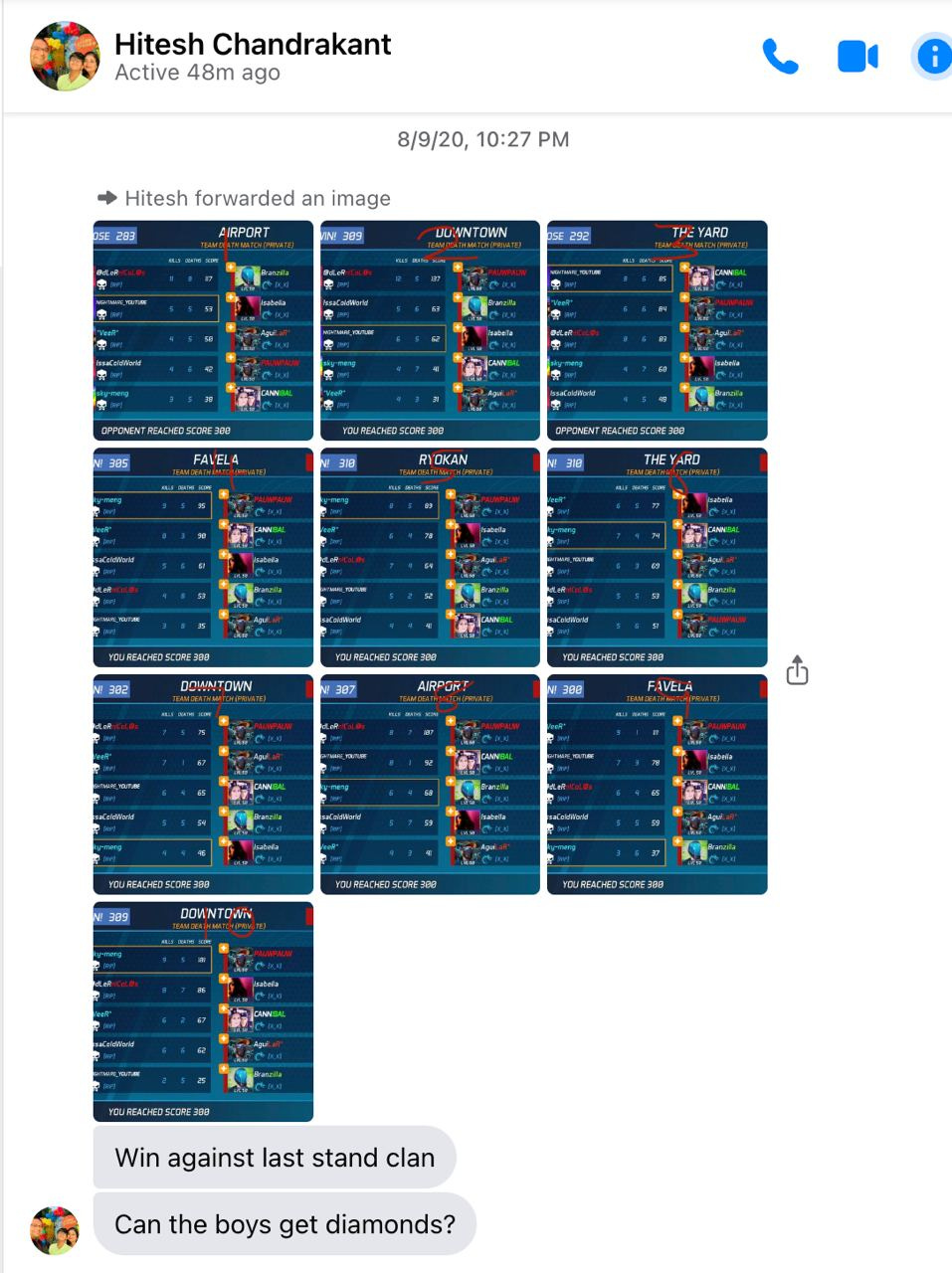

Users trading between each other is not new and has existed via users mining gold and trading entire accounts for over 20 years. I noticed it when I was helping Clan Leaders trade and transition items owned by certain of their top clan players to other lower tiered players of thier clans in games I have been developing.

I did not understand this for many years but then realized and built it as a feature within MaskGun itself sometime in 2017. Today blockchain driven ownership can do this much easier without intervention of customer support or tools.Of course it takes away the thrill that I had as a customer support guy trading virtual AK-47s and SCAR-H between Clans before a Clan War

In the absence of infrastructure for gamers to trade amongst one another, Roby had to facilitate a few transactions. His DMs are littered with texts like these. We are in the craigslist era for mobile game assets.

Effectively, there are two levers at play here. First, profit motives will keep the vast majority of the user base considerably more incentivised to build experiences or grind in-game. The game studio misses out on immediate revenue while doing this. Traditionally, a developer earned income when users purchased assets directly from the studio. But it is balanced out by reduced CAC and increased retention.

Secondly, the studio may still make more money just in royalties as gamers trade between themselves than they would have otherwise. For example, Yuga Labs and Nike have each made over $100 million in royalties through their userbase trading digital assets with one another.

What we are witnessing with Games like Axie Infinity are pioneers willing to experiment with an alternative model. For large studios like Epic and Ubisoft - it is too risky to annoy their existing users with a different model. This is also where the window of opportunity for new entrants to disrupt the incumbents lies.

The royalties aspect is not some “ground-breaking” feature that games have recently discovered, and present-day tech stacks can easily enable more developers to cut each time a user trades in-app assets. But what is unique is the proximity these on-chain primitives have to a complex ecosystem of financial primitives.

Let me explain what I mean by “proximity” here. Most new Web3 games and NFT launches today find their early user base in a crypto-native crowd. These users are accustomed to parking billions of dollars in DeFi and have spent just as much on NFTs.

Li Jin, a pioneer in all things creator economy from Variant fund, put this aspect into context when discussing the matter with her.

Using Web3 primitives in gaming gives creators the confidence that comes with owning the fruits of their efforts. It also accelerates the pace and means through which they can build their wealth. It may not be too far to see a future where creators use in-game assets with DeFi primitives to accelerate growth: tokenize revenue streams, lend against custom art, and maybe even raise investment- Li Jin

Many do not come to new Web3 primitives in pursuit of fun alone. If there is a profit motive, they will bridge assets across chains, participate in weird secret ceremonies and join in on what you are building. But along with their capital comes the know-how of how to use permissionless assets to increase profit.

We have noticed users taking loans against in-game NFTs, issuing derivatives instruments to speculate on their prices and setting up DAOs to acquire in-game assets at a bulk discount. Traditionally, these are things a game developer could not expect from gamers. Or want to attract, for that matter.

They may not want the price of an in-game asset they offered collapsing due to a liquidation cascade on an NFT lending platform. But it is the benefit and risk that comes with building on permissionless and composable instruments on the blockchain. You never know how good (or bad) things can be.

We reached out to vet these ideas with Gabby Dizon from YGG, one of the world’s largest gaming guilds:

Building user generated content on top of permissionless assets is a significant improvement over existing UGC models. It allows the player community not only to create new content but also compound network effects in ways that the original game developers never intended before. It also for fairer value transfer and ownership to the creators making the UGC.

In essence, you are trading the surety of how users may behave in a constrained environment for the randomness of users determining what happens to your product. Sounds like a fun version of a DAO.

Bootstrapping UGC Economies

Web3 native games transitioning to being UGC platforms generally follow a similar path:

All games start with the launch of a primary product capable enough to attract at least a few thousand users daily.

Once sufficient users are playing the game, introducing scarce assets that can only be earned through playing the game for long enough is the next step. These instruments generally give their holders a slight advantage regarding points earned or matches won.

Traders and gamers that generally do not want to spend days playing games acquire these instruments at a price determined by the free market.

At this point, games are incentivised to launch their in-game marketplace to deter scammers and provide a safe trading environment for users.

Assuming the marketplace has sufficient liquidity and frequency of transactions occurring organically, the developers may introduce a native asset like Robux or Fortnite’s V-bucks. The economics behind these assets would vary from game to game, but the currency could, in turn, be used to incentivise users to generate content on the game.

But why bother with any of this? Why “reward” users with on-chain instruments they can trade or take loans against? There are two aspects a product unlocks when asset ownership is passed on to the user. Firstly, instead of a developer determining what can be done in a restrictive way, you allow the user to imagine what they can do with it. It could range from creating lending markets for the assets to using it to set up a small in-game DAO.

Secondly, it helps find the fair value of assets in the game before any UGC is launched. Because if you do it before an active market, the odds are high that the platform will have many spammy experiences built to get airdrops. It’s a challenge most DeFi and NFT native products face today. Founders often don’t know the true size of their user base as the anticipation is that most users engaging with these products do it for the possibility of receiving airdrops.

Sandbox and Decentraland pioneered UGC in crypto. They incentivised creators with native tokens and gave the infrastructure to bring together traders and creators. But they missed out on the fact that ecosystems don’t sustain unless you have a large enough user base interested in using the product for fun. Traders often buy plots of land or develop experiences in anticipation of future profits.

But like the ghost cities in China, unless there are actual people that look forward to spending time in these virtual worlds, the price of these assets quickly collapses.

Strong UGCs are likely to be built through a focus on gamer motives. Web3-native games can be less fun if they can compensate for the financial aspects. Much of the users we have seen in the P2E economy come for the extra income it generates. There is an evolutionary arc a user like that may follow. With enough time spent, the user will have earned enough to buy in-game assets and trade them.

With enough profits, the gamer may rent assets to other players, similar to the guild model. At his peak (in terms of commercial value to the game) – a gamer would have sufficient skills to build unique gaming experiences, bootstrap a community around it, and earn passive income.

This evolution of a gamer, from making an income in linear correlation to time spent to proactively creating and governing in-game experiences, is what most Web3-native studios are missing out on today.

We often think that primitives in DeFi, DAOs, and NFTs are not valuable for the average person. The way to make it meaningful is by embedding them in-game and bringing together large enough userbases around them.

For instance, if an in-game creator can show sufficient promise, he may be able to raise capital from his peers by setting up a DAO. The contributors, in exchange, could be given a portion of the earnings generated through the experience. Much like we see developers in the traditional realm acquiring and developing properties, we may see studios that specialise in building experiences in Web3-native virtual worlds like Sandbox.

It may seem far-fetched today but consider that there were over 70 developers that made north of a million dollars on Roblox in 2021. And seven that did over $10 million.

As the ecosystem around Web3-native UGC evolves, we will witness on-chain targeting of the most active wallets. It will be favourable for games trying to scale to offer discounted properties and similar incentives to creators that have built good experiences in a different game.

Much like how nation-states offer incentives for entrepreneurs to move, games (and protocols) will target wallets that show the most frequency through in-game interactions.

The Creative Chasm

What we have with most of Web3 gaming today are highly transactional economies. For the trend to distil to the average person, we need to transition to being outlets of creative expression. Most social networks of the present age made that transition a decade back. Enabling creative output makes platforms fun places to hang out.

As creators go from building an audience to making substantial sums of money, they would care less about the capital and more about the influence. For them, creative expression would be at the pinnacle of their priority list. It may seem far-fetched, but consider that just last year, a user made $5 million from Fortnite's creator support programme. What is just as baffling is that he got north of $100 million in revenue to the game.

Think about how gen-z and millennials were priced out of traditional assets like real estate. We came too early for the space age. Our rights to "ownership" and the dignity that comes with it are often in digital instruments. It is unfair to compare a house in New York with real estate in Decentraland. But erly adopters of these digital realms stand to profit just as much, if not more, over the coming decade.

And unlike tech booms of the past, the internet would (ideally) make it possible for everyone to have equitable access to these opportunities. We heard similar arguments about ICOs and NFT mints. And many of them ended up being predatory to retail users. The difference is, in games, you do not stand to benefit only from being early. A creator has to build something users want. Or we end up with digital ghost towns.

The challenge for most games exploring the theme would be to balance community and profit motives. As we have seen time and again with protocols and DeFi primitives, profit motives by "asset owners" can lead to some terrible product decisions. The kind that repels users for a very long time. This is partly why introducing a UGC component in games will be gradual. You cannot bootstrap a sustainable market without a sticky community.

There is much work to be done here. Regulators will have to recognise games as work outlets instead of points of entertainment alone. Who knows, we may see in-game creator unions in the future. Investors may want to start seeing in-game experiences being developed through the same lens as SaaS products. Finally, and most importantly, there will be a learning curve for creators to understand what they can do with this newfound "ownership".

It makes us reminisce about how we thought about what one could do with smart contracts in 2016. We will leave you guys with this trailer of an interesting game based on Indo-futurism that we have been following for a while. It may have something to do with what we just wrote about.

See you next week with a breakdown of how venture funding has evolved over the past two quarters.

See you next week with a breakdown of how venture funding has evolved over the past two quarters.

Peace,

Joel John & Siddharth Jain

Written with inputs from - Gabby Dizon, Amy Wu, Justin Tay, Li Jin, Siddharth Menon, Roby John, Shlok, Aman, Piers Kicks and Mark.

Before these pieces go live, I discuss most things covered in the newsletter on our Telegram. It is where we stay updated on all things Web3 and discuss what could be next in the market. Consider joining us to connect with ~2500+ researchers, investors and operators.

Awesome piece. What tool do you use to make these images, as well as graphs? Clean af.