Unbundling the Bank

Crypto is (mostly) fintech now

Hello!

There is an API for everything, except peace, these days. With enough resources and developers on caffeine, you can build apps that book cab-rides, hotels and possibly even therapy at the click of a button. What if these APIs were used to re-invent ancient institutions?

Today’s article explores how changes in legislation will unbundle what we’ve long known as banks. We argue that if blockchains are money rails, and everything is a market, then users will eventually leave idle deposits on apps they prefer. In turn, this would compound and pile up balances in applications with massive distribution.

Everything could be a bank in the future. But how?

The GENIUS Act allows applications to hold dollars (as stablecoins) on behalf of users. It opens up incentives for platforms to encourage users to deposit money and spend it directly through the applications. But banks aren’t just vaults to store dollars. They are complex databases, layered with logic & compliance. In today’s issue, we explore how the stack enabling such a transition has evolved.

If you are building a bank or building companies that eat into what is considered one, we’d like to talk. Reach out at venture@decentralised.co.

Hello!

In the early months of running this newsletter, we had to switch between banking partners several times. Nobody quite wants to back a bootstrapped business that calls itself “Decentralised.co”, you see. After several switches, I realised a simple thing that should have been common sense. Most fintech platforms we’d been using were essentially wrappers for the same underlying banks. So, instead of chasing the next shiny payment product, we began building relationships directly with the banks themselves.

You cannot build a startup on top of another startup. You need a direct relationship with the entity actually doing the work so that if and when things break, you are not stuck playing telephone through layers of middlemen. As a founder, choosing a consistent, but slightly more traditional vendor could save you hundreds of hours, and just as many back-and-forth emails.

But why does this matter? Am I about to drop a founder’s field guide to managing ops? No. The whole process taught me two maxims that sit in contrast with one another.

In banking, much of the money is made where the money resides. A traditional bank holds billions in user deposits and may have internal teams of compliance officers. Compared to a startup with a founder worrying about his licenses, the bank may be a safer bet.

But at the same time, tremendous amounts of money can be made by sitting in the thin layer where assets pass between hands in high volume. Robinhood does not “hold” the stock certificates. Most trading terminals in crypto don’t custody their users’ assets. But they generate billions in fees each year.

These are two contrasting forces in the financial world. It’s the tussle between wanting custody & being the layer where transactions occur. Your traditional bank may see a conflict with asking you to trade meme coins with assets custodied with them, because they make money on deposits. But at the same time, an exchange makes money, convincing you that wealth is generated by gambling on the next animal token.

Underlying this friction is the shifting idea of what a portfolio even is. My grandmother in Kochi, Kerala, would have been happy with a portfolio of gold, land, and a few stock certificates. In contrast, a savvy 27-year-old today may consider her stash of Ethereum, rights to Sabrina Carpenter’s music, and streaming dividends from My Oxford Year to be a safe addition to her portfolio alongside gold and stock certificates. (Lovely movie, btw). While neither rights nor streaming dividends are currently an actual thing, the evolving nature of smart contracts and regulations may very well make them a possibility in the next decade.

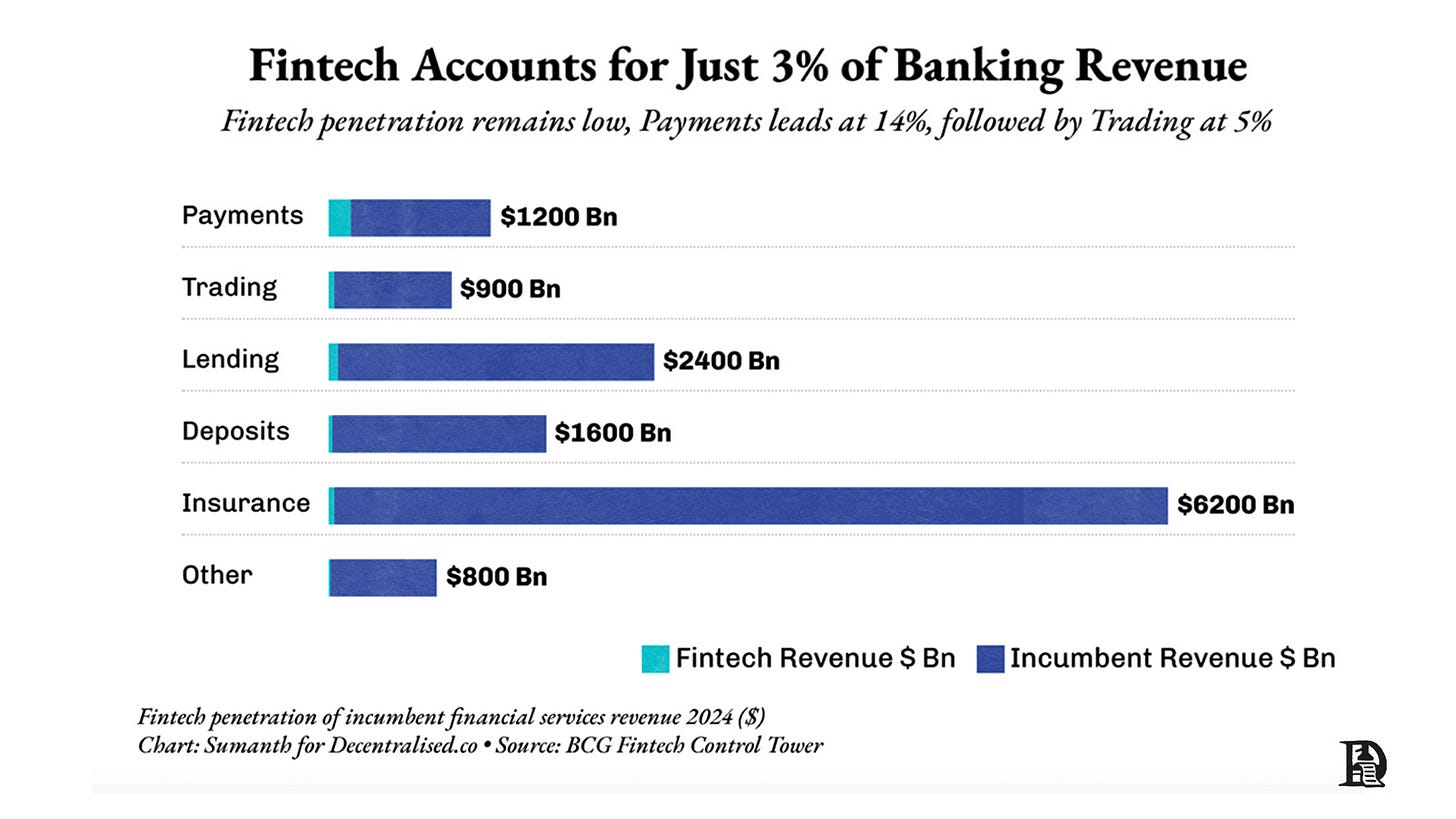

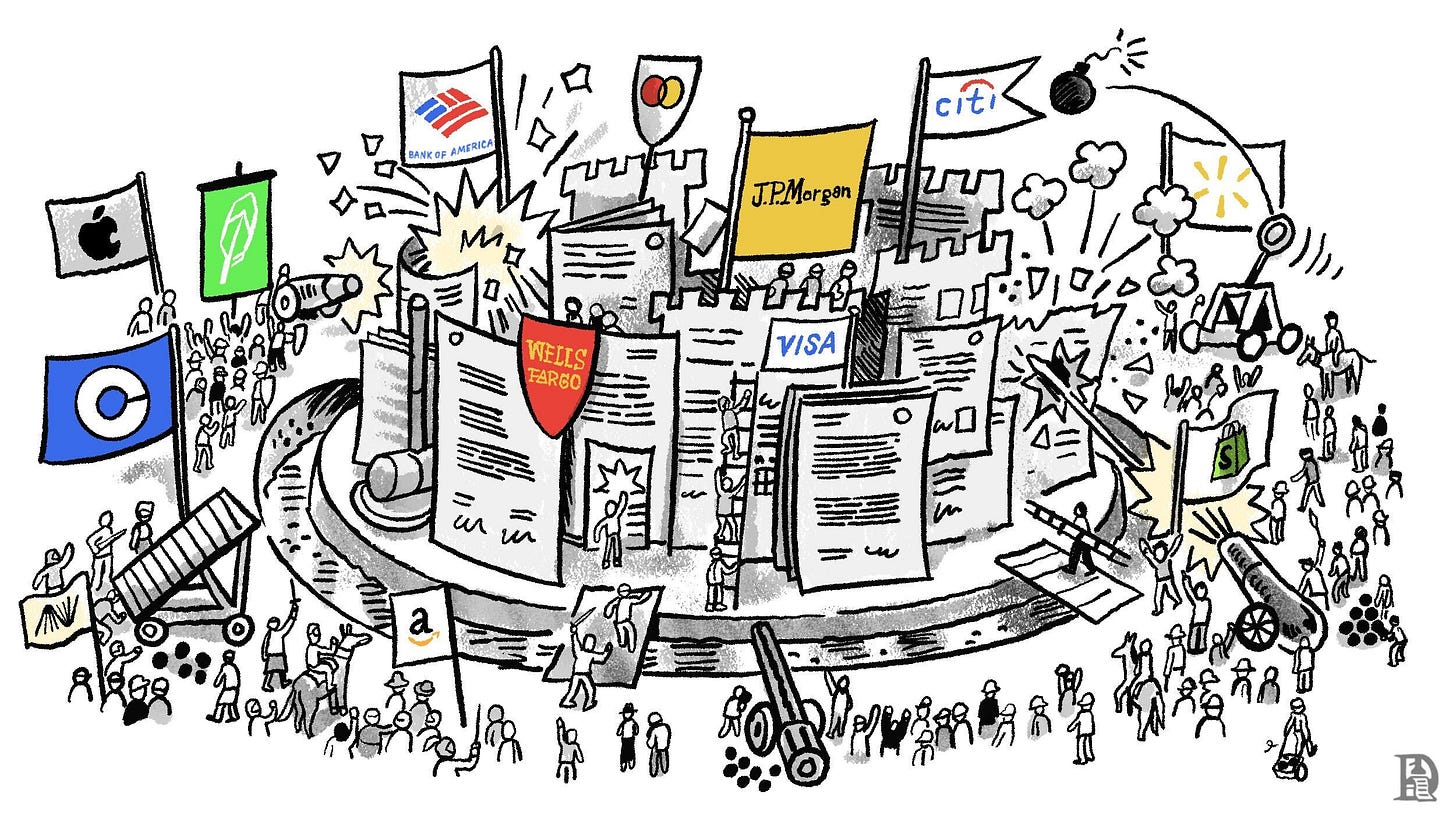

If the very definition of a portfolio is going to change, then so will the places we store wealth. Few places show this transition as well as banks do today. Banks account for 97% of all banking revenue, leaving only about 3% to fintech platforms. It is textbook Matthew Effect. Banks generate the bulk of the revenue, as much of the capital today resides with them. But can businesses be built by stripping away slices of that monopoly and owning specific functions?

We’d like to think so. It’s partly why half of our portfolio consists of fintech startups.

Today’s piece makes the case for the unbundling of the bank.

The new banks are not in shiny offices downtown. They are in your social feeds. On your apps. Perhaps, even in the cookies you generated from those suspicious searches you made last Friday night. Crypto has reached a stage of maturity where it has stopped being relevant for early adopters alone. It has begun flirting with the boundaries of fintech, making the world the TAM for what we build. What does that mean for investors, operators & founders, though?

We try to find the answers in today’s issue.

But first, let’s visit the graveyard. Of fintech startups.

The GENIUS in Liquidity

Warren Buffett is dubbed the wizard of Omaha. And for good reason. His portfolio’s performance is nothing short of magical. But underlying that magic is a little bit of financial engineering that often goes unnoticed. Berkshire Hathaway has what can be considered permanent capital. In 1967, he acquired an insurance business that saw a steady amount of idle capital. In insurance terms, he could utilise the insurance float, i.e., the amount paid as a premium but not yet claimed. Think of it as an interest-free loan.

Contrast this with most fintech lending platforms. LendingClub was a start-up focused on peer-to-peer lending. In such a model, the liquidity comes from other users on the platform. If I were to give Saurabh and Sumanth a loan on LendingClub and neither of them repays, I might be less inclined to provide a loan to Siddharth on the same platform. The reason is that by then, my trust in the platform’s ability to vet, verify, and onboard good borrowers would have eroded.

Would you ride on Uber if every time you took a cab, there was an accident?

Think of that, but for lending. LendingClub eventually had to acquire Radius Bank for $185 million to have a steady source of deposits that could be given out as loans.

In the same vein, SoFi spent close to $1 billion over seven years to scale as a non-bank lender. In the absence of a banking license, you are not allowed to take deposits and offer them out to potential borrowers. So it had to fund loans through partner banks, which ate the bulk of the interest generated. Think of it as me borrowing from Saurabh at 5% and offering it to Sumanth at 6%. The 1% spread is my earnings on issuing that loan. But if I owned a steady source of deposits (like a bank), I could earn considerably more.

This is what SoFi eventually did. In 2022, it bought Golden Pacific Bank in Sacramento for $22.3 million. The move was made to acquire a national charter that allows it to take deposits. That single change pushed its net interest margin (the gap between what it earns on loans and what it pays for deposits) to around 6%, far higher than the 3–4% typical for U.S. banks.

Smaller wrappers on banks don’t create large enough margins to operate. What about behemoths like Google? Google launched Plex as a mechanism for embedding a wallet directly into your Gmail app. It was built with a consortium of banks to handle deposits. The operation involved Citigroup and Stanford Federal Credit Union. But it never launched. After two years of regulatory back and forth, Google pulled the plug in 2021. In other words, you can own the largest inbox in the world, but struggle to convince a regulator as to why you should allow people to move money where they move emails. Such is life.

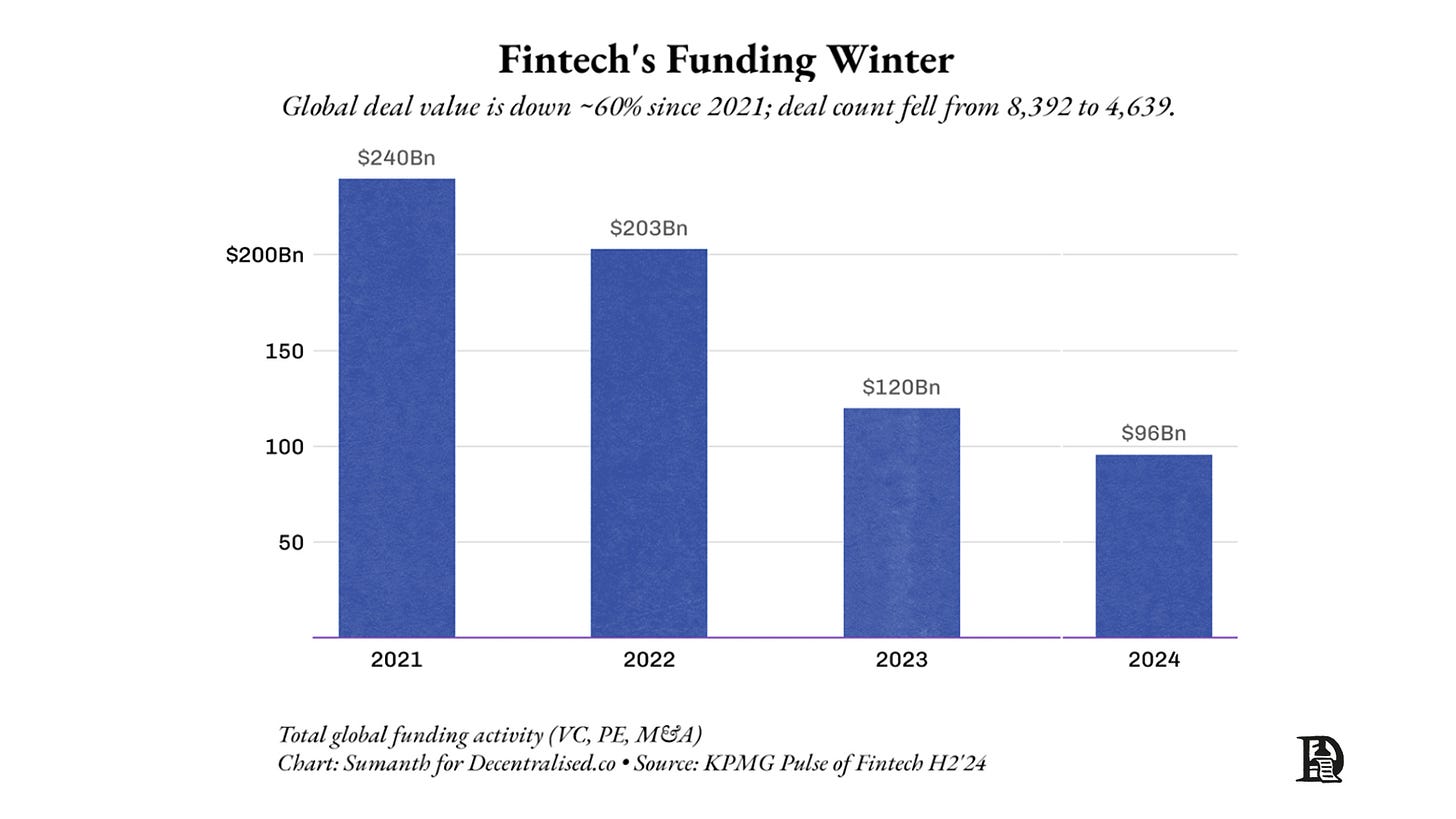

VCs understand this struggle. Since 2021, the total money flowing to fintech startups has halved. Historically, much of the moat in fintech startups was regulatory. This is why banks claimed the largest slice of the banking revenue pie. But when a bank misprices risk, it gambles with depositors' money, as we saw with the Silicon Valley Bank.

The GENIUS act eats into this moat. It allows non-banks to hold user deposits in stablecoins, issue digital dollars and settle payments 24/7. Lending is still fenced off, but custody, compliance and liquidity have slowly transitioned into the realm of code. We may be entering an era where a new age of Stripes would emerge on top of these financial primitives.

But does it increase risk? Are we allowing start-up bros to gamble with user deposits, or are we limiting it to only the suits? Not quite. Digital dollars, or stablecoins, are often far more transparent than their traditional peers. In the conventional world, risk assessment is a private affair. On the chain, or on-chain, it is publicly verifiable. We see versions of this when ETFs or DAT holdings are verifiable on-chain. You can even verify how many Bitcoins a nation like El Salvador or Bhutan holds.

What we will witness is a transition where the products may appear web2-esque, but the assets are on web3 rails. Think Transferwise, but with stablecoins.

If blockchain rails enable faster money transfers and digital primitives like stablecoins allow user deposits to be held by anyone under the proper regulatory regime, we are about to see a new generation of banks emerge with very different unit economics.

But to understand that transition, it helps to first understand the components that make up a bank.

Stable Building Blocks

What even is a bank? At its core, it does four things.

First, it holds information on who owns what amount of assets—a database.

Second, it enables people to transfer money among themselves through transfers and payments

Third, it ensures compliance with users to ensure that what is held with the bank is legal

And fourth, it uses information from the database to upsell loans, insurance, and trading products.

The way crypto is eating into each of these parts is a bit inverted. Stablecoins, for instance, are not full-fledged banks today, but they have substantial traction in terms of volume. Visa and Mastercard historically ran a toll on everyday transactions. Each swipe throws a few basis points into their moat because merchants had no alternatives.

By 2011, U.S. debit fees averaged about 44 basis points, high enough that Congress passed the Durbin Amendment, slashing these rates in half. Europe capped them even lower in 2015, with debit at 0.20 % and credit at 0.30 %, after Brussels concluded that the two giants were “coordinating rather than competing.” Yet uncapped U.S. credit cards still clear at 2.1%–2.4% today, barely lower than a decade ago.

Stablecoins bulldoze that economics. On Solana or Base, a USDC transfer settles for less than $0.20 flat, no matter the ticket size. A Shopify merchant who accepts USDC through a self-custody wallet can retain the 2% credit network once claimed. Stripe has read the tea leaves. It now quotes 1.5 % for USDC checkout, undercutting its take rate of 2.9% + $0.30.

These rails invite new players to join with much lower costs. YC-backed Slash lets any exporter start accepting U.S.-customer payments in five minutes—no Delaware C-corp, no acquirer contract, no paperwork, no lawyer retainer— just a wallet. The message to legacy processors is blunt: upgrade to stablecoins or lose the swipe revenue.

For users, the economic case is pretty simple.

Accepting stablecoins in emerging markets means saving the hassle and incredible fees associated with forex.

It is also the fastest mechanism to send money across borders, particularly for merchants with downstream payments for importing.

You save the ~2% that historically went to Visa and Mastercard. Yes, there are off-ramping costs, but in most emerging markets, stablecoins trade at a premium to dollars. USDT in India currently trades at 88.43, compared to the 87.51 offered by Transferwise for dollars.

The reason why stablecoins have been embraced in emerging markets is that the economic case is pretty straightforward. It is cheaper, faster, and safer. In regions like Bolivia, where inflation is at 25%, stablecoins offer a viable alternative to government-issued currencies. In essence, stablecoins have given the world a taste of what blockchains as financial rails could look like. The natural evolution, then, would be to explore what other financial primitives these rails can enable.

Merchants who move cash into stablecoins will quickly discover that the hard part isn’t receiving money, but running a business on-chain. Money still needs a vault, yesterday’s flows must reconcile, suppliers expect payouts, payroll wants streaming, and auditors demand proofs.

Banks wrap all this plumbing in a Core Banking System, a mainframe-era behemoth written in Cobol that maintains the ledger, enforces cut-off times, and pushes batch files.

A Core Banking Software(CBS) does two basic jobs :

Maintain a tamper-proof ledger of truth: who owns what, map accounts to customers

Expose that ledger safely to the outside world: enabling payments, loans, cards, reporting, risk management

Banks outsource this work to a CBS software provider. These providers are tech companies that excel at software, while banks excel at financial aspects. This architecture emerged from computerisation in the 1970s when branches transitioned from paper books to connected data centres, then fossilised under mountains of regulation.

The FFIEC is an institution that publishes the playbook for all U.S. banks. It spells out the rules that a core banking software should follow: keep primary and back-up data-centres in separate geographies, maintain redundant telecom routes and power, journal transactions continuously, and continuously monitor any security incident.

Switching a core banking system is a DEFCON-level event because the data, every customer balance and transaction, is trapped in the vendor’s database. Migrating means weekend cut-overs, dual-running ledgers, regulator fire drills, and a high likelihood that something will break the morning after. This built-in stickiness turned core banking into a near-permanent lease. The top 3 vendors, Fidelity Information Services (FIS), Fiserv, and Jack Henry, date back to the 70s and still lock banks into contracts that run roughly seventeen years. Together, they serve over 70% of banks and nearly half of credit unions.

Pricing is usage-based: a retail checking account costs anywhere from $3 to $8 per month, sliding down with volume but ratcheting up with extras like mobile banking. Turn on fraud tools, FedNow payments rails, analytics dashboards, and the meter climbs higher.

Fiserv alone hauled in $20 billion in revenue from banks in 2024, roughly 10× Ethereum’s on-chain fees during the same period.

Put assets themselves on a public chain, and the data layer stops being proprietary. A USDC balance, a tokenised T-bill, and a loan NFT all sit on the same open ledger that any system can read. If a consumer app decides its current “core” is too slow or too expensive, it doesn’t need to forklift terabytes of state; it simply points a new orchestration engine at the same wallet addresses and keeps moving.

That said, switching costs don’t fall to zero; they just mutate. Payroll providers, ERP systems, analytics dashboards, and audit pipelines all need to integrate with the new core. Swapping vendors means rewiring those hooks, not unlike changing a cloud provider. The core isn’t just a ledger; it also runs business logic: mapping user accounts, cutoff times, approval workflows, and exception handling. Re-encoding that logic in a new stack still takes effort, even if the balances are portable.

The difference is that these frictions are now software problems, not data-hostage problems. There’s still glue work encoding workflows, but those are sprint-cycle problems, not multi-year hostage negotiations. A developer can even adopt a multi-core strategy, one engine for retail wallets and another for treasury ops, because both point to the same canonical blockchain state. If a provider stumbles, they fail over by redeploying containers, not by scheduling a midnight data migration.

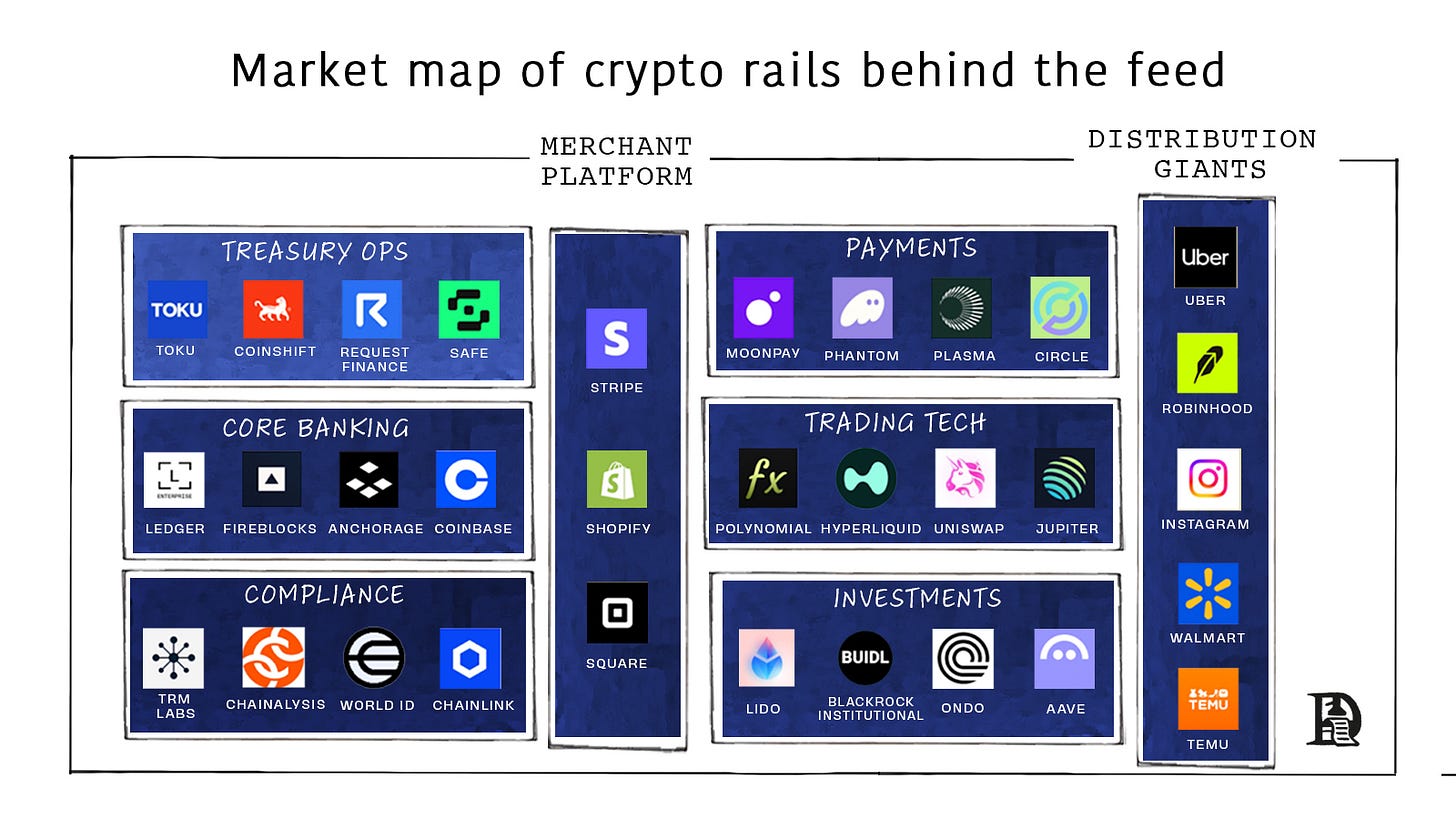

Looked through these lenses - the future of a bank could look very different. The parts exist in isolation today, waiting for a developer to pack them together for a retail user.

Fireblocks secures > $10 tn in token flow for banks like BNY Mellon. Its policy engine can mint, route, stake, and reconcile stablecoins across 80+ chains.

Safe guards ~$100 bn in smart-account treasuries; its SDK gives any app simple login, multi-sig policy, gas abstraction, streaming payroll, and automated rebalancing.

Anchorage Digital, the first chartered crypto bank, rents out a regulated balance sheet that speaks Solidity. Franklin Templeton mints its Benji Treasury Fund straight into Anchorage custody and settles shares T+0 instead of T+2

Coinbase Cloud offers wallet issuance, MPC custody, and sanctions-checked transfers as a single API.

These players have the ingredients legacy vendors lack: on-chain asset understanding, compliance AML hooks baked into the protocol, and event-driven APIs instead of batch files. Put that against a market projected to jump from roughly $17 billion today to about $65 billion by 2032, and the equation is simple: the line item that once belonged to Fidelity and friends is up for grabs, and the firms shipping in Rust and Solidity instead of Cobol will grab it.

But before they can be truly retail-ready, they need to battle the great demon that battles all financial products. Compliance. What could compliance look like in a world that is increasingly on-chain?

Compliance as Code

Banks run four kinds of compliance: they know the customer (KYC and due diligence), screen counter-parties (sanctions and PEP checks), watch the money (transaction-monitoring with alerts and investigations), and report to supervisors (SARs/CTRs, audits). It’s huge, expensive, and constant. Global spending topped $274B in 2023, and the burden rises almost every year.

The scale of the paperwork gives away the model. FinCEN tallied roughly 4.7 million Suspicious Activity Reports and 20.5 million Currency Transaction Reports last year—forms about risk filed after the fact. The work is batch-heavy: collect PDFs and logs, assemble narratives, file reports, wait.

With on-chain transactions, compliance stops being a pile of artefacts and starts behaving like a live system. FATF’s “travel rule” expects originator/beneficiary info to accompany transfers; crypto providers must obtain, hold, and transmit that data (traditionally above the USD/EUR 1,000 “occasional transaction” threshold). The EU has gone further and applies the rule to all crypto transactions. On-chain, that payload can ride as an encrypted blob alongside the transfer, ready for supervisors but invisible to the public. Chainlink and TRM publish sanction lists and fraud oracles; a transfer queries the list mid-flight, reverting if an address is flagged.

Privacy is also protected once zero-knowledge wallets like Polygon ID or World ID can carry a cryptographic badge that proves, say, “I’m over 18 and not on any sanctions list”. Merchants see a green light, regulators get an auditable trail, and the user never leaks a passport scan or street address.

Fast, liquid markets are useless if money stalls in back-office paperwork. Vanta is an example of a reg-tech startup that moved SOC2 compliance from consultants and screenshots to APIs. Startups selling software to Fortune 500 companies require an SOC2 certificate. This is supposed to demonstrate that you adhere to sensible security practices and avoid storing customer data in unprotected public links, unlike Tea.

Startups need to hire auditors who hand in a monster spreadsheet, demand screenshots of everything from AWS settings and Jira tickets, disappear for six months, then return with a PDF that expires the moment it is signed. Vanta pared that ordeal down to an API. Instead of hiring consultants, you plug Vanta into AWS, GitHub, and your HR stack; it monitors logs, takes those same screenshots automatically, and feeds them to auditors. This single trick has driven Vanta to $200 million ARR and a $4B valuation. Useful, yes, but still a screenshot tax.

Finance will follow the same arc: less binder management, more policy engines that evaluate events in real time, then leave a cryptographic receipt. Balances and flows are transparent, timestamped, and cryptographically signed, so auditing becomes watching.

Oracles like Chainlink slot in as the courier of truth between the off-chain rulebook and on-chain enforcement. Its Proof-of-Reserve feeds make reserve sufficiency legible to contracts so issuers and venues can wire circuit breakers that react automatically. Instead of waiting for an annual visit, ledgers are continuously monitored.

Proof-of-Reserve streams collateral levels block by block; if a stablecoin ever drifts below 100 % backing, the mint () function auto-locks and texts the regulators.

There’s still real work ahead. Identity proofing, cross-jurisdiction rules, edge-case investigations, and machine-readable policy all need hardening. The next few years will feel less like complying with paperwork and more like API versioning: supervisors publish machine-readable rules, oracle networks and compliance vendors ship reference adapters, and auditors move from sampling to supervision. As regulators understand what they can get with live auditing, they’ll work with providers to implement a new class of tools.

The New Age of Trust

Everything gets bundled. Then steadily unbundled. Man’s story is a repetition of his attempts at finding efficiency through rolling up things together, only to realise, a few decades later, they were best left in isolation. The nature of legislation (around stablecoins) and the state of the underlying networks (Arbitrum, Solana, Optimism), being where they are, would mean we would see repeated attempts at recreating the bank. Yesterday, Stripe announced its own attempts at launching an L1.

The modern age has two forces playing in tandem.

Rising costs owing to inflation.

Rising memetic desire, owing to how connected our worlds are.

More people will take control of their finances in an age where people’s desire to spend increases and wages stay stagnant. The GameStop rally, rising increase in meme coins or even frenzies around Labubus or Stanley mugs are the after effects of such a transition. What this means is, applications with sufficient distribution & trust embedded in them will evolve to be banks. What we will see is a version of Hyperliquid’s builder code system expanding to the entirety of the financial world. Whoever owns the distribution channels will end up being the bank.

Why would you want to trust JP Morgan, if the influencer you trust the most is suggesting a portfolio on Instagram? Why bother with trading on Robinhood if you can do it directly on Twitter? Me? Personally? My preferred mechanism of losing money would be parking money on Goodreads to buy rare books. My point is, with the GENIUS Act, the legislations that allow products to hold user deposits have shifted. More products will mimic a bank in a world where the moving components that make up a bank become API calls.

The platforms that hold a feed will be first to engage in such a transition. This is not an entirely new occurrence. Social networks leaned heavily on e-commerce platform activity during their early days to monetise, as that is where money moved hands. A user seeing ads on Facebook may buy a product on Amazon, and thereby generate referral income for Facebook. In 2008, Amazon launched an app called Beacon that specifically looked at platform activity to create wish lists. Throughout the history of the web, there has been a fine waltz between attention and commerce. Platforms embedding bank infrastructure within themselves will be one more mechanism of being closer to where the money is.

Will the old guard not jump on this trend of providing access to digital assets? The existing fintech firms wouldn't idly sit by, would they? FIS is in talks with almost every bank and knows what’s up. In his recent piece, Ben Thompson’s point is simple and brutal: when paradigms flip, yesterday’s winners are handicapped because they want to continue doing something they did when they won. They’re optimised for the old game, defend the old KPIs, and make the right decisions for the wrong world. That’s the Winner’s Curse, and it applies just as cleanly to money going on-chain.

When everything is a bank, nothing is a bank. If users do not trust a single platform to custody the bulk of their wealth, there will be a divergence in where the money sits. This already happens with crypto-native users who hold the bulk of their wealth in exchanges instead of banks. That means there will be changing unit economics for how banking revenue is generated. Smaller apps may not need as much revenue as large banks to operate, as the bulk of their operations may occur without human involvement. But that means that what we know to be traditional banks will slowly die.

In 2001, a bookstore named Borders gave the bulk of its online book sales to a scrappy, small seven-year-old startup run by a former hedge fund bro. It was called Amazon. In a decade, the bulk of the book purchases that occurred went digital, and borders had to shut down in the age of Kindles and iPads. A similar fate awaits many traditional financial institutions. Surely there will be behemoths like JP Morgan that survive and sustain. If Visa and Mastercard point to anything, the large players will lead the charge. But as with most technological cycles, the smaller ones will be eaten alive.

Perhaps, much like life, technology is simply a continuum of creation and destruction.

Of bundling and unbundling.

Signing out,

Joel

Disclaimer: DCo and/or its team members may have exposure to assets discussed in the article. No part of the article is either financial or legal advice.

Something I am desperate to see is decentralized identity. It would make age gating and proof of human so much easier and more secure. Are any of these players working on that? Seems like a natural for Coinbase given their user base.