On Gaming, Guilds and GameFi

A thesis on the future of gaming

TL;DR: Today, Siddharth Jain from IndiGG and Sumanth, join me for our next thought experiment. We will try to understand why we as humans enjoy gaming so much, what the emergence of web3 (also known as Web 3.0) means for our society and economy, and how gaming guilds could be indeed the future of gaming

Hey there,

I really hope you managed to spend some time away from the screens this weekend. The last week was a bloodbath for the equity markets. It made me realise why the traditional world does not trade on the weekends. Meta (Facebook) had close to $250 billion in value ripped off its market capitalisation within one work week. It seems as though the market does not believe in Mark Zuckerberg’s vision for what the metaverse could look like in the future. (But we’ll save that discussion for a future piece.) For today, I want to shift your focus to a different aspect of the metaverse: Gaming. Over the last few months, the gaming industry has seen four unprecedented acquisitions:

Microsoft acquired Activision Blizzard for $68 billion.

Take-Two Interactive, the company behind Grant Theft Auto, the most profitable game of all time, acquired the social game developer Zynga for $12.8 billion.

Sony purchased Bungie, the studio behind Halo and Destiny.

ByteDance (TikTok) acquired the video game developer Moonton for $4 billion through its gaming unit, Nuverse.

Looking at these major market movements, it almost seems like the gaming industry operates in a separate world of its own, where the broader equity market shakeouts don’t exist. But why is that? For one, gaming is now a $300 billion industry, eclipsing every other form of entertainment. For a sense of scale, TV is at $100 billion, and the movie box office is at $40 billion. Often, we can predict where the future is leading us by understanding the past. So let’s take a look at the following ancient artwork together:

The painting above is situated in an old limestone cave in Indonesia. It is considered one of the oldest cave paintings in the world. But think about this: Both the caveman that painted it and I engaged in the same fundamental activity, although I spent hours gaming and he spent hours painting. We were both creating an alternative world, imagining a different, fantastical reality. Games open pathways to imaginative roles that are often crucial in helping children pick up useful skills. As kids grow up and engage in play, they learn about social hierarchy, coordination, good and evil, and communicating without words through games. But why do we play digital games? What makes millions of us sit glued to our screens for hours on length in an era of declining attention spans?

Good games identify the core activity and make it enjoyable. A good core loop puts the player in a state of flow. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi defines this as an activity where the mind finds just enough challenge and ease to be engaged for long enough periods of time. Effective games combine incredible storytelling and graphical imagery with activities that induce flow. But why do they induce flow? Perhaps because it appeals to the most human of behaviours: Roleplay. One way to view everything – from religion to government – is that it is an elaborate act of roleplaying. And society functions because we assume roles and stick to them. Gaming reduces the barriers and friction to roleplay to a fraction of what it is typically. This appeals to the human desire to switch roles and be in control of an environment. Want to go on a rampage, killing people with 128 players? Wish to be an emperor handling armies in Age of Empires? How about being a smooth assassin changing the course of history? Gaming makes it possible to be who and where you would rather be in a matter of clicks, for a fleeting moment.

A different way to think about gaming is through the lens of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. It appeals to human desire on multiple levels. At the physiological level, it gives humans an escape from their existing environments as I just mentioned. On the safety level, gaming enables the discovery of micro-communities on the web, thereby returning a sense of tribe and comradery to the gamer. Not bad for a generation deemed the loneliest ever! Within the micro-community, gamers make friends (and lovers, if lucky) thanks to the number of hours spent doing the same thing in virtual worlds. Gamers that are able to climb up the hierarchy go on to lead guilds or compete at international levels to have elevated levels of esteem. Consider watching this video explaining Red Dead Redemption’s most well organized community for context. At the highest levels, games allow their users to find self-actualisation through gainful employment, praise through competing in esports or empowering newer gamers to climb up the ranks. I think this is part of what makes gaming more interesting than other consumer segments like dating apps and social media. They can immediately strike multiple sections of our hierarchy of needs. I reckon much self-actualisation does not happen on dating apps in comparison. I won’t be waxing poetic about games much longer. This was context for the non-gamer readers.

From web2 to web3

The earliest era of games followed the same logic of selling toys. They were sold once and updated every few years. Gaming studios made the most money at the time of a game’s release much like movie studios do today. The average game could cost anywhere between $50 to $100, so gamers had to consciously make a big decision when buying games. The arrival of the internet meant you could update these games remotely from time-to-time and more importantly, connect gamers to one another. Games could now charge for a downloadable content (referred to as DLC) and extend the amount of time they could make money from a game sold. This model is prevalent with large games like Far Cry 5 and Just Cause 4 even now. As the industry became more competitive, we saw vertical bundling happening and subscriptions became a thing. Instead of selling individual games, subscription models allowed gamers to access a library of hundreds of games.

This meant a larger user base would flow towards the games offered in the subscription and revenue would continue to grow long after a game is released. Apple does this with mobile gaming apps today. Microsoft and Sony have a variation of this for Xbox and PlayStation. Revenue from both these models are surpassed by the sale of digital goods. Digital goods in games sell well as they have socio-economic context. Consider a community of one million gamers. Rare items that are either acquired through possessing a certain amount of skill, or through purchasing at heavy prices signal status. The larger the community, the higher the value of tools that determine status. At some point in time in the last decade, gaming studios recognised that it is better to offer a game for free and focus on selling small items in-game. These could be unlocks of new weapons, aesthetic changes to a character, or in-game money. The chart below comparing how Xbox' revenue streams went from retail sales to online revenue is good context on how the industry's business model went digital.

Micro-transactions in games are far stickier than large purchases because -

The low price of the purchase generally means less cognitive load.

Customers tend to buy multiple items over time leading to a larger revenue per user.

It opens up the game for a large user base which in term means a larger funnel to upsell digital goods.

There is an argument to be made here that the pricing is optimised to be on the lower end as it means children can often buy $1-$2 items without bothering their parents but let’s not go there. Web3 gaming models run on somewhat similar economics with a few caveats:

Ownership

Web3-based applications focus primarily on users owning their data. In the context of gaming, this extends to in-game assets. Users should be able to transfer, trade or use the in-game asset in a different game if they decide on it.Liquid Economies

Most games we see with a token first focus have reward systems that are linked to a token. These are somewhat similar to in-game points except in this case, a user can withdraw and sell it for actual cash. This is the underpinning for what makes play to earn economies function.Interoperability

This is a thesis that has not played out yet but if assets are transferable and underlying economies can be traded on, then it makes sense for in-game assets also to be interoperable. Assume you spent 50 hours playing one game, you start from scratch on another. What if the resources earned in the game could help accelerate your experience in the next game? Users owning their in-game assets mean that it is likely that they will be able to sell it to get an edge on the new game they play.

The Challenge of web3 Native Games

Functionally, web3-based games combine blockchain-based infrastructure with financial incentives to empower gamers economically for the time they spend on games. This is at the heart of what makes web3 gaming equal parts addictive and repulsive. On one end, games are supposed to be fun. As I had said earlier, games are a way of escaping the grind. But there have been economic agents (or workers) that do work in exchange for monetary benefits since the early 2000s. RuneScape, Farmville or GTA 5 – all of them have a thriving market where gamers that are skilled or have time are compensated by others looking to move faster in the game. The great challenge for most web3-oriented games is to find a fine balance between exceedingly financial aspects and the fun aspects of a game. Modern life runs on belief in a meritocratic society because if we were told only those with money would win, most of the populace would choose not to play in the first place. The same is applicable to game design. If they are designed such that only users willing to pay money can win, then the userbase will simply dwindle. In turn, it would make the overall gaming experience worse for those that can afford to pay too because nobody likes playing alone. Philosophy aside, there is one more aspect to gaming that makes it unique.

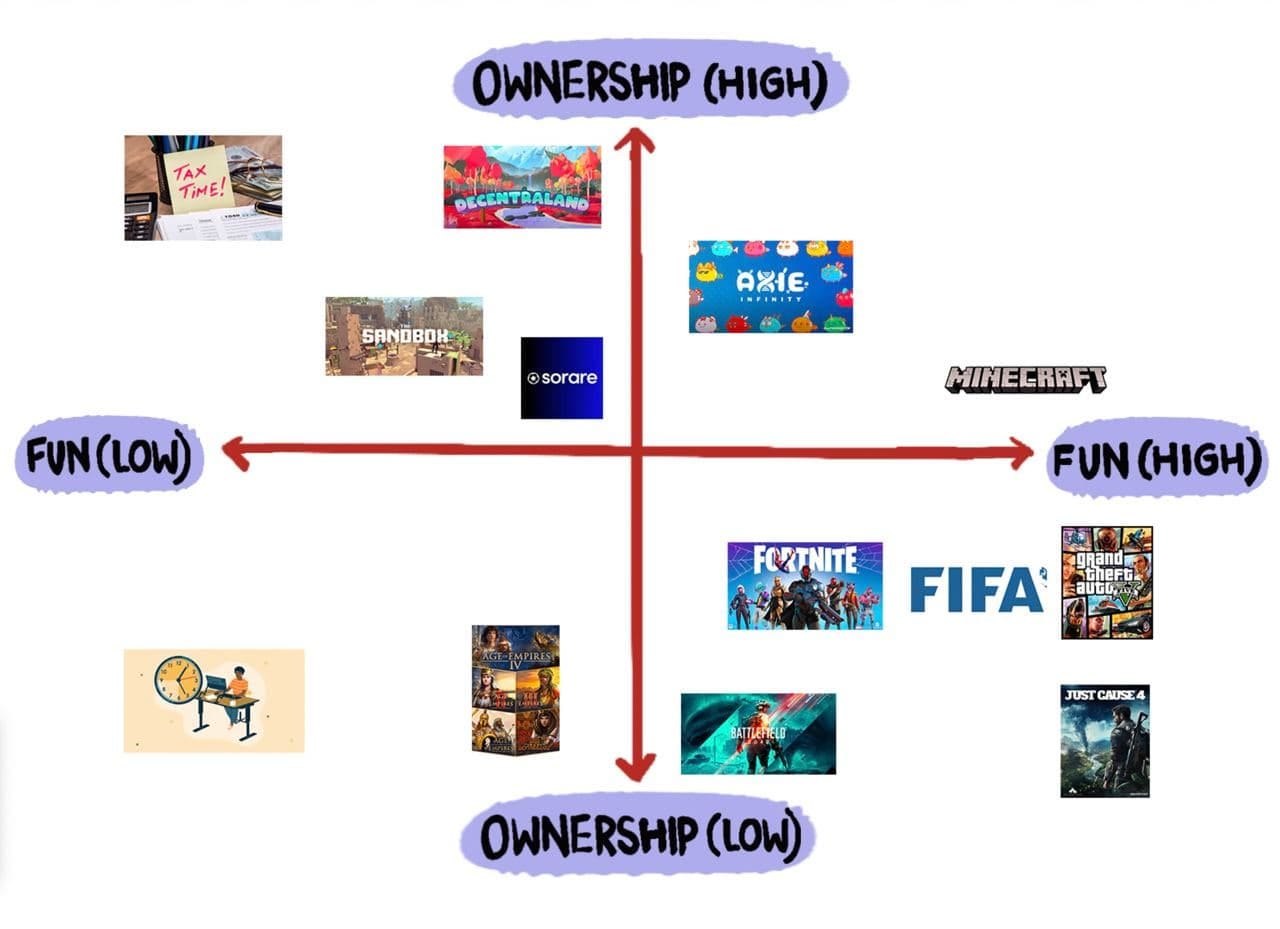

Games in their current format are zero-sum. Gamers have to focus on a single game at a time and within that, they are forced to optimise on limited parameters. Users constantly have to trade between building wealth (through ownership of assets) or having fun. The quadrant below somewhat explains it. Limitations in present day gaming architecture would mean the most graphically intense games cannot be optimised for users moving assets all the time. Think about hits like Just Cause or GTA 5 - they are optimised to be visually appealing and fun. Not for customisation or asset ownership. Axie on the other hand allows asset ownership but limited customisability. The outlier here is Minecraft, where individuals can set up their own servers with its own variables and choose how it is run. At the extreme end of low ownership and low fun - you have taxes and grunt work. Both of which belong to the default game we find ourselves in. Real life.

This is part of the reason why the trade-off matters so much. An individual choosing to have fun (in say GTA 5) may miss out on potential earnings from a play to earn game (like Axie). This is applicable to game design, too. The moment when income potential from a game beats real life wages is when users see it as an avenue to work instead of using it for leisure. Now, let's think of web3 games in context of Maslow’s hierarchy. I had earlier mentioned how a game is typically able to address multiple aspects of Maslow’s hierarchy. Present day play to earn economies focus excessively on generating income. To a point where some critics have begun calling grinding in P2E (Play-to-Earn) economy a bullshit job . The term is used to refer to work that does not contribute positively to a person’s growth and exists solely because it is not cost effective to be replaced by a machine… yet. While there is some logic to it, it is worth mentioning that P2E economies allow participants a better alternative than what is often easily available to them. If it is more cost effective to take a conventional job, it would simply be logical to do that instead of playing P2E games. Secondly, working in environments like those of Axie Infinity’s allows participants to pick up on the kind of soft skills needed to collaborate and coordinate in a digital first, remote work environment. Something traditional academia fails to do today. Thirdly, most people playing these games don’t start and end it with a single game. P2E economies are crucial, incentivised on-ramps for individuals to upskill and learn about alternative opportunities in the market. This is where a crucial rebrand is in the works. From play to earn to play and earn. Most web3 native games will evolve from being a single source of income to one that supplements other sources of income. A crucial component enabling that transition will be what is referred to as guilds.

Guilds & GameFi

Guilds are platforms for coordinating resources within games. In the context of web3 native games, they are socioeconomic platforms built atop DAOs. Certain games like Axie Infinity require the gamer to own a certain number of NFTs before they can play. There could be requirements of owning tokens too in some of the newer games that come to market. Guilds reduce the barrier to entry for a large number of new entrants in to the web3 gaming ecosystem by making it possible to game without owning the NFTs or tokens. How? Well, you see, there’s an entire industry built around “leasing” NFTs to individuals who then grind in terms of gaming in play to earn economies. The guild functions as a DAO that owns the NFTs, and tokens required to play. Individuals that find skilled gamers are referred to as managers. They are similar to scouts in the sporting world and receive a cut from revenue generated by gamers. The gamers in turn receive a portion of the token rewards that come from playing. This is a very rudimentary model used to accelerate adoption of P2E ecosystems.

It is our understanding that guilds will soon evolve into something much bigger and that will have lasting impacts on the future of gaming, work and culture. Since guilds are functionally on-ramps that on-board large number of users, they will soon be streamlined into sources of attention. Much like how we have Twitch being the go-to streaming platform for traditional games today, web3 native streaming platforms will emerge to encourage creators focused on the web3 gaming ecosystem. Guilds will be able to use their community to find supporters for a winning team, raise money for social causes or just bring people with similar interests together. We already saw a wave of this occurring quite recently with the YGG community oncoming together to raise capital for a typhoon in the Philippines. As users gather around these guilds, it will be natural to see a hierarchy of gamers emerge from it. The most talented gamers will be empowered with additional resources (like gaming merchandise and sponsorship) to compete in large e-sports tournaments. It will become commonplace for guilds to sponsor teams from their own community to take a portion of the winnings

The single largest missing component of DAOs or guild-based work today is that it lacks the sense of security a traditional job gives. No healthcare, pension, or in many cases even banking access for those employed by a DAO. There are a number of ventures seeking to solve this issue, but a crucial piece of the puzzle is guilds themselves becoming financial conglomerates. What if guilds used a portion of their cashflow to acquire stakes in emerging games? Or, given their long-term outlook on the industry, they could hold a curation of scarce NFTs for much longer periods of time. In this case, an effective guild will be more akin to large pension or endowment fund and will be a highly preferential partner for newer P2E games to strategically raise from. The ideal guild is a financial conglomerate with cashflow, assets, and growing investments in its books. There are some platforms enabling this transition. Openguild.io for instance is enabling individuals to invest into revenue streams for guilds. GuildOS is a venture enabling the effortless management of large-scale guilds. Meanwhile, BreederDAO aims to build analytics and NFT issuance layers for large P2E games. (Note: We need a market-map for guild related applications. I will be setting up a $1,000 bounty for readers wanting to build one.)

Guilds offer an indexed bet into web3 gaming ecosystems as they are often exposed to multiple games. The key commodity in web3-based games is not IP, or the infrastructure games are deployed on. It is the userbase. Guilds have the most proximity to them. Investing in them is one way for investors get an indexed bet on the gaming and NFT ecosystem. In our opinion, the gradual evolution of guilds is to become large-scale financial applications catering to specific needs of their userbase. A guild specific bank would offer remittance, insurance, forex and its own internal lending desk that assesses credit-worthiness on basis of a gamer's reputation. Ultimately, the evolution of guilds will be into full-stack fintech apps.

What does all of this really mean though? In our opinion, the gaming ecosystem will evolve in the next few years because of the culmination of three key factors:

COVID-19 started the Great Resignation in early 2020. People quit their old jobs to seek new meaning – and income – from non-traditional sources. And games are evolving to be a good source of that for a rapidly growing part of the population.

The educational ecosystem has failed an entire generation, that is now looking for alternatives for both upskilling and higher income. P2E ecosystems enable just that, albeit not at scale yet. The business models here are still underexplored. What if we could simply pay individuals to upskill themselves? The concept of Learn-to-Earn is already becoming common in some fringe parts of the market.

We have barely scratched the surface of what GameFi (i.e., when players can trade, lend, or rent out their game winnings or borrow against them) could evolve into. Lending against NFTs? Why not against in-game reputation? How about income sharing with the next big streamer? Derivatives for in-game NFTs? There’s a sea of models to tinker with and it is too early to write off the ecosystem.

The one issue I see with the theme today is that investors may give high valuations to ventures with terrible unit economics. If I were building on the theme - I would be focused first and foremost on value capture, unit economics and profitability.

I will see you guys tomorrow with a story on a venture doing just that in the traditional fintech world in India.

P.s - Make sure to come hang out in our Telegram if this piece interested you. I am far from a gaming expert and would love to learn from you.

Off for a walk at the beach,

Joel

_________________________________________________________

This piece was made possible with a sponsorship from Nansen. The platform saves analysts and traders hundreds of hours each month by allowing them to grab network level data with a simple click. No APIs, no going through network scanners or pulling contract addresses. Nansen visualises network level data on user behavior & transactions in a fraction of the time their peers do. Get started with a trial here or simply play with their dashboards here.

_________________________________________________________